Anila Ilyas was wide awake, keeping an eye on the road outside from her fifth-floor apartment. All her belongings were packed and she was trying her best to stop her three teenage sons from falling asleep. When she saw a group of policemen arrive at her apartment building in Bangkok’s Pracha Uthit area, on that night in September 2015, she moved quickly but silently and evacuated from the back door along with her children.

Forty-five-year-old Anila was an Urdu teacher in a missionary school in Lahore before she left for Thailand in September 2013, joining thousands of Pakistani Christians living there illegally. They are constantly in hiding or on the run to escape arrest, detention and deportation. After arriving in Bangkok, Anila, too, had changed more than 10 houses.

In the Pracha Uthit building, 35 Pakistani Christian families lived in single-room apartments — 66 people were arrested from there that night for overstaying in Thailand.

“We cannot go out because of the fear that the police may arrest us,” says Anila. (This is not her real name — which is being held back to protect her from arrest). “We force our children to keep their voices low to avoid detection by police. Neighbours make a complaint to the police if our children make a noise,” she says in a phone interview from her latest hiding place in Thailand.

Language barrier and illegal status together hamper these migrants from getting jobs. Anila works as a teacher to make ends meet while her husband has remained unemployed since their arrival in Bangkok.

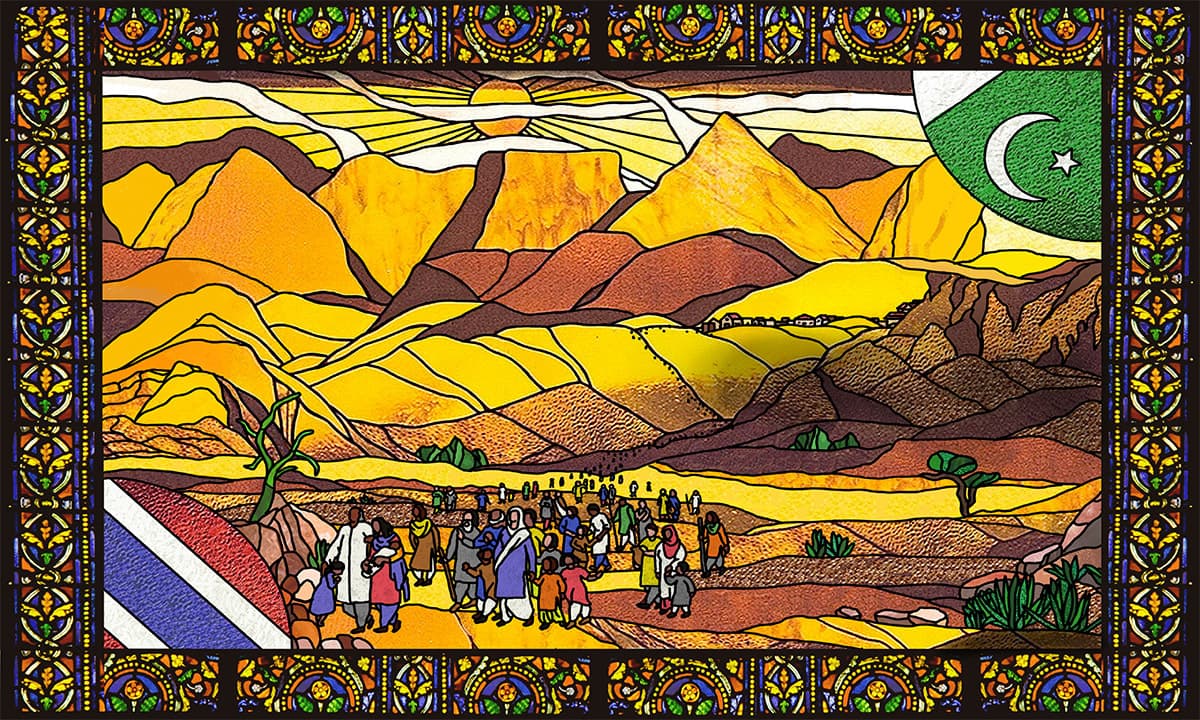

Faced with cultural, political and economic isolation, Christians in Pakistan embarked on two different trajectories of migration.

Immediately after arriving in Thailand, mostly on visit or transit visas, Pakistani Christians approach the local office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), hoping they will be resettled in Europe, Australia or North America. Though they start receiving some financial support from charity organisations to buy their daily meals but usually they have next to nothing to pay for other utilities. “Paying the monthly house rent is the biggest challenge,” says Anila. A single-room accommodation can cost as much as 2,400 baht (7,250 rupees) a month.

World Watch Monitor, an international Christian news wire, notes that about 11,500 Pakistani Christians have approached the UNHCR to get refugee status in recent years. Though exact country-wide statistics are difficult to find out, a large number of these requests have been filed in Sri Lanka, Malaysia and Thailand.

The Thai government, however, does not want Pakistani Christians to enter its territory. “[It] has made it extremely difficult for Pakistani Christians to obtain Thai visas,” says Pastor Mubarak Masih, 40. If a Pakistani Christian manages to obtain the visa, he is highly likely to be found out at a Pakistani airport since his passport shows his religion, says Mubarak Masih who arrived in Thailand in 2013 with his wife, two sons and one daughter. Once detected as Christians, the passengers are often off-loaded from flights leaving Pakistan. Those who still manage to fly out are taken to the Immigration Detention Centre (IDC) once they arrive at their desitation. Their relatives or UNCHR have to bail them out.

Mubarak Masih used to run a small church from his home in Lahore’s Youhanabad area and was “always fearful for security”. Those were not idle fears. In March 2015, two suicide bombers attacked two churches in Youhanabad, killing 15 people and hurting more than 70 others.

Another constant in the pastor’s life was a Punjabi word – chuhra – used as a derogatory term to categorise people in his racial group. Difficult to translate, the word connotes dark skin, low social status and untouchability.

In Thailand, he and other Pakistani Christians are facing another identity crisis. “Even taxi drivers call us ‘bomb’ and ‘Bin Laden’ when they find out we are from Pakistan,” he says.

Hameed Masih, 75, had a big family. His wife, eight sons, the wives of six of his sons and his many grandchildren all lived in a small two-storey house in a Christian neighbourhood, along a railway line in Gojra town of Punjab’s Toba Tek Singh district. In August 2009, hundreds of angry protesters set ablaze more than 50 houses and a couple of churches in the neighbourhood. They were enraged over reports that a Christian family living in another locality, Korian, a small settlement a few kilometres outside Gojra, had blasphemed.

The arson took the lives of Hameed Masih and five members of his family: his 55-year-old son, his two daughters-in-law (both under 30 years of age), his four-year-old grandson and his eight-year-old granddaughter. They had a guest that day — a daughter-in-law’s 50-year-old mother. She was also killed in the attack.

About 11,500 Pakistani Christians have approached the UNHCR to get refugee status in recent years.

Once the dead were buried, the rest of the family decided to leave Pakistan. All of them, except Hameed Masih’s son Ilyas Hameed, went to Thailand and filed an application with the UNHCR for refugee status. “So far, the UNHCR has resettled five of my brothers along with their families in the United States,” says Ilyas Hameed who lives in Rawalpindi with his wife and children. His brothers live in Pennsylvania where they work as day labourers, he says. His sixth brother, Babar Hameed, is still living in Thailand waiting to be resettled in Canada.

The successful resettlement of Hameed Masih’s family has become a popular narrative among Christians living in different parts of Punjab. Thousands of them have sold their properties and left for countries where they can file a request for refugee status.

Talib Masih, a waste-paper collector, found a crowd gathered outside his house in Korian on July 30, 2009. The people at the head of the throng were alleging that he had committed blasphemy by setting fire to papers carrying Islamic text. The mob blocked the nearby road, raised passionate religious slogans and finally attacked the houses of Christians living in Korian, burning them all down.

Before the attack started, every Christian living there had fled except Hanifan Bibi, 73, and her 80-year-old paralysed husband Sharif Masih. “I pleaded with the attackers that we could not run. They did not harm us then,” says Hanifan.

Also read: Acts of faith: Why people get killed over blasphemy in Pakistan

She claims the mob attack was a premeditated plan to grab the land where Christian houses were built. “The place was still on fire when people brought measuring tape to see how much land they could take over.” The Christians did not own the land. It belonged to the government – recorded as shamlaat-e-deh, the extension of the village land earmarked for collective usage.

The Christian neighbourhood razed only days later in nearby Gojra is also housed on government land. “It is a prime location. The main bus terminal and the railway station are only at a walking distance from here,” says Yasir Talib, a local resident. Many here believe the attack that killed Hameed Masih and his family members was an attempt to take away the neighbourhood’s land from Christians.

A few years later, a similar pattern was in evidence in Lahore. Joseph Colony – a Christian slum of more than 200 houses also situated on government land – was set on fire by a rampaging mob in 2013 after allegations that a local Christian had committed blasphemy. The neighbourhood is surrounded by industrial units and is next to the bustling commercial area of Badami Bagh. The residents of the colony claim they have been under pressure since long to vacate the land. During the March 2013 proceedings of a suo motu hearing about the attack on Joseph Colony, the Supreme Court, too, suspected that land grabbing could be the reason behind it.

The Punjab government later paid 500,000 rupees to each Christian family that had lost its house in the attack. But there has been no announcement that they will also own the land where their houses stand, says Billa Masih, who runs a grocery store in the locality.

It is difficult to verify these claims — that land grabbing has been the only – or even the major – motivation behind these incidents. Many scholars believe that such killings actually took place because of the perceived association between local Christians and the United State of America. “… [A] general anger against the United States has caused large numbers of people to target Christians, whom they associate with America, as scapegoats,” wrote Akbar S Ahmed – who holds the Ibn Khaldun Chair of Islamic Studies at the American University in Washington, DC – in a 2013 op-ed piece in The New York Times. Mob attacks, by their very nature, are difficult to reduce to a single reason.

Yet, the presence or absence of farmland and housing facilities has been at the heart of recurring patterns of migration among Punjabi Christians over the last many decades.

In 1947, there were two types of Christians in what was then known as West Pakistan: landless, unskilled, poor labourers and peasants living in villages across central Punjab, and educated Christian professionals, mostly Anglo-Indians and Goans, who lived in big cities such as Karachi and Lahore. The former are generally converts to Christianity from low-caste Hindus and the latter from upper-caste Hindus as well as Muslims.

The Christians did not own the land. It belonged to the government – recorded as shamlaat-e-deh, the extension of the village land earmarked for collective usage.

Anglo-Indians and Goans immediately faced discrimination in jobs and business opportunities in the newly created Pakistan. Their rather privileged social status under the Raj – that prized their English language skills and British cultural mannerisms – started waning. Punjabi Christians, on the other hand, were always treated with contempt due to their caste and their dark skin.

Faced with cultural, political and economic isolation, Christians in Pakistan embarked on two different trajectories of migration. Punjabi Christians started leaving villages to shift to Church-developed Christian-only neighbourhoods in, or just outside, main cities. Anglo-Indians and Goans left in droves to Europe and North America.

They formed the bulk of the first wave of Pakistani migrants to Europe and the United States in the 1960s and the 1970s, according to Patricia Jeffery, a British researcher who investigated migration trends among Pakistani Christians in the early 1970s.

At Partition, S P Singha was the most prominent leader of Punjabi Christians. Before joining politics, he worked as a registrar at the Punjab University during the 1930s. In 1947, he was Punjab Assembly’s speaker and one of the three Christian members of the assembly who voted in favour of Punjab becoming a part of Pakistan.

His decision was based on pragmatic considerations. He thought Hindus discriminated against Punjabi Christians more than Muslims did. “In non-Muslim villages, we have no graveyards and are not allowed to draw water from the wells,” he told Sir Cyril Radcliffe’s boundary commission.

Additionally, the partition of Punjab being proposed along religious lines meant that there would be more Punjabi Christians living in Muslim-dominated western regions of the province than in the eastern parts dominated by Hindus and Sikhs. When the boundary commission announced its scheme for partitioning Punjab in June 1947, eastern (Indian) Punjab had only 60,955 out of 511,299 Punjabi Christians at the time.

Indu Mitha, 86, a famed educationist and renowned exponent of Bharatnatyam who now lives in Islamabad, has vivid memories of those days. Her mother was S P Singha’s cousin and her father, Gyanesh Chandra Chatterji, was a professor of philosophy at Government College, Lahore. (Indu Mitha’s husband, Aboobaker Osman Mitha, retired as a major general from the Pakistan Army and is credited to have founded its Special Services Group, the commando unit.)

“S P Singha, whom we called Purke Maamoon, one day called my father and told him that he had met with Mr Jinnah and told him that Christians were very poor and could not travel to India and that they wanted to live in Pakistan,” says Indu Mitha. “Jinnah assured Singh of full protection for the Christians.”

The military government of General Ziaul Haq – that took over power in 1977 – only expedited Christian departures.

Renowned Pakistani historian Ayesha Jalal records this turn of events in her book, Self and Sovereignty, albeit from a different perspective. “In their dress, poor economic status and religious beliefs, Christians in the Punjab were closer to the Muslims,” she wrote and quoted Singha as saying that Christians “trust the Muslim more.”

Right after 1947, Singha was removed as the speaker of the assembly through a no-confidence motion. Reason: He was not a Muslim. That turned out to be a symbol of how life was to change for Punjabi Christians in Pakistan.

Singha addressed the assembly on January 20, 1948 to highlight that change. “Kindly pay attention to the mess created by the Sikhs who, after living for centuries in this province, have at once left and have created a huge problem for [Christians]. The government may have better information but our estimates show that about 60,000 families or 200,000 people of our community, who worked as saipis (landless service providers) or atharis (farmhands), have become homeless after the commotion of Partition,” he said.

The lands vacated by the Sikhs were being allotted to Muslim refugees coming from eastern Punjab and these new owners of land either did not want Christian saipis and atharis due to religious reasons or they did not know them well enough to trust them with such jobs. “They hired us for a while but then they engaged their coreligionists,” says Nazir Masih who was about 13 years old at the time of Partition and was living in Harichand village in Sheikhupura district.

In some cases, Christians were forcefully evicted even from places where they were tilling lands for the state institutions – such as in a few villages set up on the military farms. “Christians are being evicted from some of the villages reserved for them,” Singh said. “They are being replaced with [Muslim] refugees.”

Singha argued that Christians in Pakistan deserved protection from the government because they “have taken refuge in this House of Islam”. When no one listened to him, he suggested to the government to either place the homeless Christians in refugee camps or “bury them alive”.

The number of homeless Christians kept on increasing in the meanwhile. C E Gibbon, another Christian member of the Punjab Assembly, noted in his statement on the floor of the house in April 1952: “I beg to ask for leave to make a motion … to discuss a definite matter of urgent public importance, namely, the grave situation arising out of the policy of the government in respect of the wholesale eviction of Christians … from their home holdings, thus rendering nearly 300,000 Christians homeless and on the verge of starvation, the consequences of which are too horrible to imagine.”

Earlier, in 1948, Singha had highlighted another problem. He described how young Muslim students were harassing Christian nurses, insisting that Christian women in Pakistan were like war booty and the Muslims possessed the right to use them whichever way they liked. “If this mindset continues, then I fear there will be no Christian nurses left in Pakistan,” he warned.

Also read: Brotherhood thrives in Karachi's religiously diverse quarters

Singha also talked about how Christians in Pakistan were viewed with suspicion. “… [the Christians] are ready to assure the government of Pakistan of our loyalty but sadly we are being accused of committing strange things. One group of people says we are spies and another says we are agents of Hindus.” He went on “to humbly state” that the government should “stop demanding” that Christians prove their loyalty to the state everyday as “Muslims are required to do in India”.

It was natural, says Michelle Chaudhry, 48, a Christian activist in Lahore, that “every Pakistani Christian was feeling low because they were always suspected of spying for India”. Her late father, Cecil Chaudhry, was a flight lieutenant in the Pakistan Air Force during the 1965 war and a squadron leader in the 1971 war. He and other Christian military officers earned official and public recognition for their courage and military exploits during those two wars. That stemmed the tide of anti-Christian sentiments to some extent, she says.

But only to some extent. “After the 1965 war with India, there were some reports of ‘reprisals’ against Christians in Pakistan,” noted Patricia Jeffery, professor emeritus of sociology at the University of Edinburgh, in her book, Migrants and Refugees: Muslim and Christian Pakistani Families in Bristol.

The National Council of Churches Review, a journal published by the Wesley Press, noted in 1971: “It has become a fashion in West Pakistan to accuse Christians of espionage and they are being told to migrate to other countries, particularly Canada and the United States.”

Singha argued that Christians in Pakistan deserved protection from the government because they “have taken refuge in this House of Islam”.

Though S P Singha’s son, D P Singha, who was also a member of the Punjab Assembly, declared that those who “thought that Pakistani Christians had sympathy with India were wrong,” the Muslim perception of local Christians did not improve. The journal quoted the Bishop of Lahore, Inayat Masih, as saying the government exhibited a step-motherly attitude towards Christians.

In early 1971, all this culminated in what is perhaps the first mob attack against Christians in Pakistan. A Pakistani living in Manchester wrote to Lahore-based English daily Pakistan Times, “complaining about a book called The Turkish Art of Love in Pictures (first published in 1933), which he said … contained insulting assertions about the Holy Prophet.”

The publication of the letter led to large-scale attacks on Christians in Lahore. Churches were ransacked and liquor shops (which were legal at the time) were looted. Jeffery quoted one Christian woman as imploring during the violence that “Christians in Pakistan should be seen as ‘true Pakistanis’ and that there should be no stigma attached to being Christians.”

Nationalisation of education further heightened social tensions between Muslims and Christians. Christians were enraged when, on March 29, 1972, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto – then working as chief martial law administrator of the country – nationalised private educational institutions, including those run by the Christian missionary organisations. Muslims were happy that Christians would not be able to use education to spread their religion.

Angry Christians in Rawalpindi took out a protest procession against Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s decision. They marched towards the Governor House to present a memorandum. In an attempt to stop them, the police opened fire on them – killing two people, Nawaz Masih and James Masih, on the spot.

Muslim protesters, too, came out against Christian missions. “There were protests by Forman Christian College Lahore students and others against foreign missionaries after which they hurriedly left the country,” says a Sri Lankan missionary who was working in Pakistan at the time. He wants to remain unnamed due to security reasons.

Soon a resolution was tabled in the National Assembly. Pauline A Brown, a former American missionary who worked in Pakistan between 1954 and 1988, recorded it in her 2006 book, Jars of Clay: Ordinary Christians on an Extraordinary Mission in Southern Pakistan. It reads: “…the resolution calls for the taking over by the government of all institutions known or running as missionary schools, colleges, hospitals, and nursing homes ... The resolution also demands that foreign missionaries should leave Pakistan and no visas or any permission in future be granted to foreign missionaries to operate in this country.”

By that time the exodus of educated Pakistani Christians was already well under way. “Most immigration took place for economic reasons,” says Victor Gill, who was a teacher of physics at the Forman Christian College Lahore in 1976 when he decided to leave Pakistan. “Higher education, sponsorship by relatives and theological training were few of the vehicles used for migration,” he says in a phone interview.

Gill went to Philadelphia which, according to him, has the largest Pakistani Christian concentration in North America after Toronto. The choice of the destination has its roots in Presbyterian missions’ activities in Punjab dating back a century. With its headquarters in Philadelphia, the Presbyterian Church had sent such prominent missionaries as Dr Samuel Martin (who founded a Christian-only village in Punjab), Andrew Gordon (after whom the Gordon College Rawalpindi is named) and Dr Charles William Forman (the founder of the Forman Christian College Lahore).

Nationalisation of education further heightened social tensions between Muslims and Christians.

Jeffery, too, found a sizeable Pakistani Christian community living in the English city of Bristol. They wanted themselves to be seen as Christians first and Pakistanis later, she noted. She also found out that Pakistani Muslim migrants maintained ties with their relatives back in Pakistan but “the Christians mix more with people who are not kin, including British people, and the ties which they retain with kin in Pakistan are very weak.”

That did not guarantee easy assimilation. Several Christians, she wrote, “complained that British people refuse to accept their claims to common [religious] allegiance”.

The military government of General Ziaul Haq – that took over power in 1977 – only expedited Christian departures. Many prominent Pakistani Christians, including Michael Nazir Ali, left Pakistan in those years to avoid religious persecution at the hands of a dictatorial regime that had the self-declared agenda of Islamising every part of public and private life in the country.

Ali was working as Bishop of Raiwind when he left Pakistan. “I was asked by the then Archbishop of Canterbury to leave for [some] time because of difficulties and threats to the family resulting from my work with the very poor, – especially in brick kilns – and in resisting some of Zia’s policies affecting women and minorities,” Ali says in an email interview. “Local extremists, vested interests and some related elements in our community were involved” in creating the circumstances that led to his exile. Ali now works as Bishop of Rochester in England.

Presbyterian missionaries from the West started setting up schools and colleges across Punjab during the last quarter of the 19th century. They set up Forman Christian College in Lahore in 1864, Gordon College in Rawalpindi in 1883, Murray College in Sialkot in 1889, St Stephen’s College in Delhi in 1881 (Delhi at the time was a part of Punjab province), Edwardes College in Peshawar in 1900, Kinnaird College for Women in Lahore in 1913.

The stated objective of these educational institutions was to educate the upper classes in the subcontinent and introduce them to Christianity. “A plan to build up a Christian community in Delhi became instead a plan to promote Christian influence among the non-Christian elite by creating Christian institutions to serve them,” wrote Jeffrey Cox, a professor of history at the Iowa University, in his book, Imperial Fault Lines: Christianity and Colonial Power in India, 1818-1940.

The British records in 1855 show there were no native Christians in Punjab at the time. But because of the huge missionary efforts, there were about 4,000 native Christians in the province by 1881. They were a scattered and diverse urban community.

The missionaries were also working simultaneously on converting the native villagers to Christianity. Mass conversions started at places in Sialkot district in 1870 and spread to adjacent districts of Sheikhupura, Lahore and Gujranwala. Because of the mass conversion, the Christian population of Punjab increased from about 4,000 in 1881 to 511,000 by 1941.

Also read: Why divorce is close to impossible for Christians in Pakistan

Patricia Jeffery noted in her book that this dramatic swell in the number of Christians also changed their educational composition: “According to the 1936 Gazetteer for Lahore District, 58.5 per cent of Christians were literate in 1901, while only 16.3 per cent were literate in 1931. In the interim, the number of Christians (in Lahore) had risen from 7,296 to 57,097.”

That explains why there always have been two distinct classes within Christians in this part of the world – a small educated urban community and a much larger population of illiterate, unskilled, landless rural folks.

“[Being] indiscriminately associated with the word chuhra has played havoc with the psyche, identity, self-image and well-being of Pakistani Christians.”

The United Presbyterian Church, which was also the church of the downtrodden back in the US, took the initiative to bring the most marginalised and oppressed caste of scavengers, described in missionary reports and British census documents as chuhras, into the fold of Christianity. The people belonging to this community were socially excluded, living outside villages and facing serious discrimination in their everyday lives.

Denzil Ibbetson, Punjab’s deputy superintendent in the 1881 census, who later also worked as the province’s Lieutenant-Governor, has written in detail about these converts. “They prefer to call themselves Chuhra,” he wrote. He also noted their occupations. “In the east of the Province he sweeps the houses and villages, collects the cow dung, pats it into cakes and stacks it, works up the manure, helps with the cattle, and takes them from village to village”. In other areas, they worked as “agricultural labourer” and “receive a customary share of the produce”.

Because of their landlessness, Ibbetson associated them with gypsies. “Together with the vagrants and gypsies they are the hereditary workers in glass and reeds, from which they make winnowing pans and other articles used in agriculture.”

Manu Smriti, or The Laws of Manu, the most authoritative Hindu scripture on the caste system, categorised them as executioners. “[You] shall always execute the criminals, in accordance with the law,” it said while assigning Chuhras their duties. The jail employee who tied the noose around Bhutto’s neck in 1979, Tara Masih, came from the same community as did his father who had executed the anti-British hero Bhagat Singh in 1931.

Dr J W Youngson, a Scottish Presbyterian cleric, wrote in detail about these converts in James Hasting’s classical 1910 Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics: “The Chuhras of the Punjab and Central India ... were, until a comparatively late period, an unnoticed race; but the fact that many of them are becoming Christians has made them better known, and created an interest in their history and religion. It was observed by Ibbetson, in the Punjab Census Reports, that the religion of the Chuhras is nearer Christianity in its principles than any other religion in India. Briefly, these principles are as follows: There is one God; sin is a reality, man is sinful; there is a High Priest (Bala Shah), who is also a Mediator, to whom they pray; sacrifice is part of the worship of God; the spirit of man at death returns to God; there will be a resurrection of the body; there will be a day of judgment; there are angels, and there are evil spirits; there is heaven, and there is hell. The Chuhras have no temple, but only a dome-shaped mound of earth facing the east, in which there are niches for lamps that are lighted by the way of worship.”

A settlement for local converts to Christianity in what is now Nankana Sahab district is called Youngsonabad. It was set up to celebrate Youngson’s work among local Christians.

There has been an early realisation among the converts about the pernicious impacts of the word chuhra on their lives. Dr Azam Gill, who teaches English at a college in France, has written in an article that highlights the problem: “[being] indiscriminately associated with the word chuhra has played havoc with the psyche, identity, self-image and well-being of Pakistani Christians.”

They have been trying different things to get rid of the social stigma attached to the word. By the 1930s, they were being called Isai – after Isa, the Arabic translation of Jesus. In the 1961 census in Lahore, all those who had been categorised as belonging to chuhra caste in previous censuses were now classified as Isai, noted John O’Brien, a Christian priest who has written an exhaustive ethnographic account of the native Punjabi converts to Christianity.

The same 1961 census put the profession of Isais as sweepers. That association has turned the word Isai also as infected, generating an ongoing movement among Punjabi Christians to change their last names and their caste to Masih and Masihi, respectively. A heated theological debate rages on whether these words – which both refer to Christ – can be used for ordinary Christians, but that has not stopped Punjabi Christians from shedding Isai in the favour of Masih or Masihi.

Baba Sadiq is close to a century old. A tall man with sunken cheeks, he was born in a village called Nazir Labana in Sheikhupura district. He was one of the first people in his village to convert to Christianity. “We used to worship Bala Shah, a statue made of mud. There was no religious scripture or ritual, except that we bowed before the statue and distributed choori (crushed bread mixed with ghee and sugar),” he says.

His relatives – Maulu, Lahnoon, Kama, Kala, Sohan, Gahnoon – who lived in a nearby village, Taamkay, converted to Christianity and pressurised his family to also convert. “They brought religious preachers from Sialkot and converted my father Sundar who was head of our clan in the village.” Following Sundar, all members of his caste living in Nazir Labana – about 40 households – converted to Christianity.

Sadiq continued to live in the same village till Partition but then shifted elsewhere. He now lives in a Christian Colony in Lahore district’s Wandala village. His movement represents a larger pattern.

It was observed by Ibbetson, in the Punjab Census Reports, that the religion of the Chuhras is nearer Christianity in its principles than any other religion in India.

The United Presbyterian Church, Church of Scotland, the Salvation Army, Church of England and, later, the Catholic Church and Methodist Church set up about 20 villages in Punjab in the late 19th and early 20th centuries to bring together scattered local converts in order to improve their socio-economic conditions. Most of these villages are in Khanewal, Kasur, Faisalabad, Gujranwala and Sheikhupura districts. Probably the most famous ones among them are Martinpur and Youngsonabad, both in district Nankana Sahib.

Martinpur was founded in 1898 by Dr Samuel Martin who belonged to the United Presbyterian Chruch. “Christians were brought from Sialkot and Gurdaspur to inhabit the village,” says Jehangir Fazal Din, whose great grandfather, Fazal Din, came from Jammu to Punjab to attend a missionary school and converted to Christianity. “His family excommunicated him due to his conversion so he settled in Sailkot with his wife and children. When Martinpur was founded, he came here along with his family.” The other inhabitants of the village worked as farmhands of Sikhs in their native areas.

Also read: Christmas in Pakistan

A 1911 report in Southern Workman, a Christian journal published by Hampton Institute, portrays Martinpur as a model settlement: “… it will serve as an ideal illustration to show what Christianity does for the pariah.”

Living up to its founding objective, Martinpur has produced several people who stand out for their educational and professional achievements. Jehangir, for instance, is working as a high court lawyer while his father, David Fazlud Din, retired as a district and sessions judge in 1960. Perhaps the most prominent native of Martinpur is Samuel Martin Burke. He was a diplomat (having worked as Pakistan’s envoy for Scandinavia and Canada) and the author of a number of books including Pakistan’s Foreign Policy: An Historical Analysis (1973), The British Raj in India: An Historical Review (1995) and Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah: His Personality and his Politics (1997).

Henry Felix is another major founder of Punjab’s Christian-only villages. A scholar on Tibetan studies, he arrived in Punjab in 1891 and founded the village of Maryamabad in Sheikhupura district in 1893. “[Felix] attracted to Maryamabad hundreds of untutored aborigines. He settled them on the mission lands, and taught them … how to earn an honest living. Living amidst the natives, far from the haunts of civilization, he came to speak and write Urdu and Punjabi,” an America-based Catholic journal wrote in 1912, with an unmistakable whiff of white man’s burden to civilize the darker races.

In 1900, the British government of India put land at his disposal for setting up another village. The new village, now in Faisalabad district, came to be called Khushpur — “happy town, Felix-Town,” as the journal noted. Shahbaz Bhatti, federal minister for minority affairs, who was murdered in early 2011 in Islamabad, was a native of Khushpur.

Around 1909, Catholic missionaries also encouraged Punjabi Christians to settle as tenants and peasants in the vast tracts of land given to the royal Indian army to grow cereals and produce dairy products for its internal consumption. “Father Felix brought Christians here from Sialkot including my great grandfather Labba Masih,” says Younus Iqbal. He heads one of the two factions of the movement that Okara military farms’ tenants are running, demanding ownership of the land their ancestors have been cultivating for more than a century.

These model villages were able to provide decent living conditions to a few thousand Christian converts. Still most of them remained dependent on Sikh landlords and worked for them as their hired hands. That changed in 1947 — only for the worse.

In Harichand village in Sheikhupura district, a well was reserved for local Christians. After Partition, a Muslim migrant from India came to the village and claimed the government had allotted him two acres of land around the well. When he stopped local Christians from using the well, they sought help from Christians in neighbouring villages. Together, they formed a fighting group armed with guns. The migrant was also helped by other migrants in the same manner. The two sides were on the verge of opening fire at each other when some men came on horses from nearby villages and urged them not to fight. A panchayat then went through the records and found that Christians had no valid claim over the well because it was built on land under collective ownership as shamlaat-e-deh.

“We had to leave the village,” says Nazir Masih, an old man who lived in a Christian neighbourhood in Lahore till two months ago when he died. The displaced Christians settled on unoccupied land in what would be Lahore’s first Christian katchi abadi, or slum, along Ferozepur Road near where Shama Cinema was later built. “Our houses would wash away every year with rains.”

After they landed in the cities, Christians had limited economic opportunities. They could work at brick kilns – that were springing up next to big cities to cater to the booming housing and construction sectors. Those who took up that option set themselves up for bonded labour for life.

According to the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan, the number of bonded labourers in different sectors of Pakistan’s economy could be anywhere between three million and eight million. A large portion of that number works as brick layers and Christians form one of the biggest groups within them. “Relative to their percentage of the total population, a high proportion of bonded brick-kiln workers in Punjab are Christians,” as is noted in Contemporary Forms of Slavery in Pakistan, a recent report by Human Rights Watch, a New York-based research and lobbying group.

The earliest Punjabi Christians in Quetta lived in two colonies established by the municipal authorities.

The other option was to take up menial government jobs as sanitary workers. Traditionally, low-caste Hindus worked as sanitary workers in the cities that became part of Pakistan but, in 1947, most of them went to India.

Alice Albinia in her book, Empires of the Indus: The Story of a River, described how the aftermath of anti-Hindu violence in early 1948 in Karachi, then the capital of Pakistan, underscored the problems created by these departing Hindus. “Within a month of the riots, the government realised, to its alarm, that something entirely unexpected was happening: among the fleeing Hindus were the city’s sweepers and sewer cleaners.” She wrote that the “outraged residents of Karachi … regretted, cajoled and complained” in letters they wrote to daily Dawn.The city “had become an unhygienic disgrace” where “streets were littered with stinking rubbish.”

According to Albinia, “there were enough jobs for two thousand cleaners, and not enough people to do them.”

The government thought Punjabi Christians would be happy to do that kind of work. When offered those jobs, however, they were anything but happy. “I have heard that Christians are refusing to work as sweepers,” S P Singha said in his 1948 speech. “One deputy commissioner complained to me that Christians do not want to do menial tasks and refuse to pick up cow dung and dead animals,” he added.

He then told a tragic tale. In Nathain Khalsa village near Bhai Pheru (a town about 60 kilometres to the south of Lahore), Muslim migrants from India demanded that local Christians remove dead animals. The Christians refused. The migrants then cordoned off Christian houses and killed five of them, including a pregnant woman.

The story stresses the wrong stereotype that migrant Muslims had of local Christians — that by virtue of their dark skin and low social status, they should be doing the dirtiest jobs. Many, if not all, Punjabi Christians, however, only had the experience of working as farmhands and agricultural labourers. “We had never thought of picking up a broom and cleaning streets,” says Mehtab Masih, born in 1936 in a village in Sheikhupura district.

Yet, in 1952, he shifted to Mirpur Khas in Sindh along with his family and worked there as a sweeper for almost four decades. Scores of others now living with him in an exclusively Christian colony in Mirpur Khas have the same story.

Quetta’s Christian community is in mourning. Just a day earlier, on August 6, 2016, five young Christians from the city died when flash floods hit Zardalo area in Balochistan’s Harani district, about 110 kilometres to the east of Quetta, where they were picnicking.

The mood is somber at the Bethel Memorial Methodist Church, near the city’s railway station. The faithful – over a hundred in attendance on this Sunday, August 7, 2016 – are gathered to offer prayers for the departed. The pastor, Simon Bashir, is giving a sermon on the fruits of faith, knowledge and the gift of prophecy. His voice echoes across the worshippers, listening attentively as their children chase each other through the pews. When he finishes his lecture, two volunteers begin collecting alms and the choir, accompanied by a tabla and sitar, breaks into a hymn in Punjabi:

Oh Lord, our heavenly King

Thy name is all divine

Thy glories round the Earth are spread

And over the heavens they shine

In the first row of pews stands William Jan Barkat. A man with a slight built and approaching 70, he is rarely seen without a rosary in his hand. For the past 15 years, he has been a central committee member of the Pahtunkhwa Milli Awami Party (PkMAP) – a part of the provincial coalition government in Balochistan.

Although not affiliated with the Bethel Memorial Methodist Church, Barkat still comes here every Sunday for mass. His reasons are sentimental: his father – Barkat Masih who moved to Quetta from Daska town in Punjab – was once a pastor here. “I was born here. I grew up here,” he says, as he strolls along the church ground.

The church was originally built by American missionaries in 1888. Like everything else in Quetta, it was destroyed in the 1935 earthquake and was later rebuilt. Barkat explains how he is currently in the midst of renovating a memorial site dedicated to Christians killed during the earthquake. Almost buried among shopping plazas and various under-construction sites on Quetta’s Jinnah Road, the memorial is a piece of local heritage that can be easily overlooked.

When the British built Quetta, Punjabi Christians came along with them, working in the army, in hospitals, in schools and in menial municipal jobs. “Christians from Punjab started coming to Quetta much before Partition,” says Asiya Nasir, a Christian member of the National Assembly who lives in Quetta. “My maternal great grandfather was serving in the British army and he came from Gurdaspur (now in Indian Punjab) before the famous earthquake,” she says.

The trend continued. After Partition, many Punjabi Christians began moving to Quetta for employment or missionary work. Nasir’s father came to Quetta from Sialkot in 1965 as part of this wave of migration. There are, according to data put together by the church and community organisations, around 30,000 Christians in Quetta; another 40,000 to 50,000 of them live in the rest of Balochistan. But these figures are both old and disputed. Nasir, for instance, says there are more than 100,000 Christians in Quetta alone.

After they landed in the cities, Christians had limited economic opportunities.

Then there is also evidence that Christian migrants from other parts of Pakistan continue to shift to Quetta. One of these recent migrants is the pastor at the Bethel Memorial Methodist Church. Bashir moved to Quetta about eight years ago and is doing a PhD on early Christian arrivals in Balochistan. “In Karachi, there is so much competition and there are fixed and narrow views about Christians in Punjab,” he says as he explains the ongoing phenomenan of Christian migration to Quetta.

The earliest Punjabi Christians in Quetta lived in two colonies established by the municipal authorities. Over the years, as they grew in social status and became more educated, they moved out of these colonies. Some settled in neighbourhoods with mixed population. Others founded new Christian-only neighbourhoods.

Many Christians who retired as sanitation workers from the army once lived in the garrison area but they were asked to vacate their homes during General (retd) Pervez Musharraf’s regime. “Most of them shifted to Nawa Killa (a village on the outskirts of Quetta). A small Christian colony, however, continues to exist within the cantonment,” Barkat explains.

Later the same day, a Sunday school is being held at the church’s ground. The children are re-enacting a Biblical story about Samson and Delilah. At the end of it, volunteers ask them to explain the lesson they have learnt. One of the older boys eagerly raises his hand: “From Samson’s story, we learn that we should never trust anyone.” He uses the Hindi word vishvaas for trust before one of the volunteers sternly corrects him. “Bharosa,” he says and smiles, slightly embarrassed, as his class-fellows burst into laughter.

Protectively watching them from the corner of the room is their teacher, Margaret James. “Have you seen the children’s work?” she asks as she points towards religious paintings on the wall. An elderly woman with a white dupatta wrapped around her, James has been teaching at the Sunday school for the past 20 years. She is a bit of an institution in the city herself, having been in the profession of teaching for over 50 years. She has taught the children of many prominent residents of Quetta, including the sons of Jamsheed Marker, a former senior diplomat who has represented Pakistan in many capitals as well as at important international forums. “Wherever I go, I meet an old student of mine,” James says in a clear, authoritative tone that indicates her sophisticated upbringing and education.

Her grandfather migrated to Balochistan from Sialkot in 1902. A Muslim convert to Christianity, he worked as a librarian. After her father died, her mother was appointed as a tutor in 1945 for the children of the Khan of Kalat who headed a confederacy of Baloch chiefdoms before 1948 when it was merged with Pakistan. “He gave my mother a lot of respect: he sat with her, ate with her. When my mother would recite from the Bible in the morning, he would come and listen to her,” James recalls the Khan of Kalat.

Her mother also taught the children of various other Baloch chieftains, including the Raisanis and the Bugtis. “We lived among the Baloch. There was no discrimination. When Pakistan was created, the Khan of Kalat said no one would disturb the minorities in his kingdom,” says James. Even today, “we feel very safe in our places of worship and are provided sufficient security”.

So why is Quetta, a city known for suicide bombings, sectarian violence and deadly disturbances related to Baloch separatist politics, considered a haven by Christians?

Also read: The myth of freedom: What it means to be free in Pakistan

“Not a single case of blasphemy is registered against Christians in Balochistan,” says Nasir. “There are no incidents of forced conversion of women, and Christians enjoy equal economic opportunities.” Many of them are in civil service. Others are working in education and medical sectors.

Barkat, a Punjabi in a Pakhtun nationalist party, says this is because politics in Quetta is still largely ethnic and tribal (as opposed to religious) and the dominant political narrative remains secular (though there are many who doubt that). “The young ones in Balochistan still follow the ideologies of [such Baloch and Pakhtun nationalist leaders as] Ghaus Bakhsh Bizenjo, Abdul Samad Khan Achakzai, Ataullah Mengal and Akbar Bugti,” Barkat explains. Religious minorities align themselves with either Baloch or Pakhtun groups and, in return, get their religious, economic and security problems attended to.

Kaleem Siddique, editor-in-chief of Urdu-language weekly Aftab, mentions a time when Punjabis in Balochistan – all seen as settlers, their religion notwithstanding – faced serious threats after Nawab Akbar Bugti’s assassination in a military operation in 2006. “We were being targeted on the basis of our ethnicity,” he says, but then adds quickly: “The situation is much better now.”

When the British built Quetta, Punjabi Christians came along with them, working in the army, in hospitals, in schools and in menial municipal jobs.

His newspaper focuses on covering non-Muslims living in Balochistan and is distributed in 20 to 30 cities and towns in the province. He hails from Narowal and moved to Quetta about 25 years ago.

One of the major reasons for better economic and social life for Christians in Quetta is the high rate of education among them. When the British left the city, Punjabi Christians inherited all the schools built by the colonists. Many of the top schools in Quetta are still owned by Christians and run by church organisations. Even when Bhutto nationalised missionary educational institutions elsewhere in Pakistan, in Balochistan he could not. “Baloch chiefs took a bold stand for our schools so priests and nuns kept providing education in the province,” says Nasir.

Yet, this island of peace and harmony is surrounded by a very volatile sea. “If anyone says we are not provided security, they would be wrong. But the entire Pakistani nation is in a state of war,” says Bashir, the pastor.

As if to underscore that, a suicide blast hit Quetta’s Civil Hospital the very next day, leaving 69 Muslims and one Christian dead.

Sixty-five-year old James Masih – slender and beset with breathing problems – is an unlikely candidate for becoming a malik, a title reserved for Pakhtun tribal chiefs in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (Fata). He is neither a Pakhtun nor does he head a tribe. He has been living in Parachinar, the capital of Kurram Agency, all his life along with his family and about 1,500 other Christians. Yet, in 2012, the government made him a malik, with the right to represent his Christian community in local disputes and the responsibility to work with the administration of tribal areas if and when needed.

James Masih and three of his five sons are sweepers by profession as were his father and grandfather. The latter, a Punjabi Christian, migrated to Kurram in the early part of the 20th Century when the British were consolidating their military presence here.

Today, thousands of Christians live in six of the seven tribal agencies. Orakzai is the only agency with no recorded Christian population. Even the tribal agencies of South Waziristan, North Waziristan, Bajaur and Mohmand – all wrecked by religious militancy and military operations to counter that – house 1,500, 2,000, 500 and 700 Christians, respectively, according to the 1998 census data. Their ancestors all came here from Punjab.

Wilson Wazir, one of the 1,500 or so Christian residents of Khyber Agency, says his grandfather Said Masih came to Landi Kotal in 1914 from Sialkot. In March 2015, the government decorated Wazir with the Sitara-e-Imtiaz, one of the most prestigious civilian awards in the country, for his services to his religious community in Fata.

Not a single case of blasphemy is registered against Christians in Balochistan.

The objective of his work is to raise the economic profile of his community. None of the Christians in the tribal areas, for instance, own property. They all live on government land. He wants that to change. Most Christians in Fata work as sweepers. That is another thing he wants to change though it is much easier said than done. When the youngest son of James Masih managed to secure a bachelor’s degree, the only job the tribal administration could offer him was that of a sweeper. He has now moved to Turkey.

“Until recently, Christians here could not even acquire a domicile certificate or the national identity card,” says Wazir. “But now there are several educated Christians who are serving as nurses and teachers and are doing clerical jobs in government offices,” he says.

On September 22, 2013, two explosions at Peshawar’s All Saints Church took the lives of more than 80 people and injured 100 or so others, almost all of them Christians. This was a terribly tragic wake-up call for the city’s tiny Christian community.

Like everywhere in Pakistan, most Christians living in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa have Punjabi origins. And, again like elsewhere in the country, they are not immune to security threats. In many cases, those threats are compounded by social and economic isolation.

Patras Masih, one of the 450 or so Christians living in Swat, complains his coreligionists suffer from a serious crisis of employment and housing. “Most of us can find jobs only as sanitary workers,” he says.

Around the time of Partition, his family was living in Rawalpindi. After he grew up, he came to find work in Swat where his paternal aunt was working at the house of the area’s commissioner. “The social and economic conditions of Christians are very bleak in Swat,” he says. “We do not even have a graveyard to bury our dead.”

Ayub Khawar, 43, is a pastor at the Victory Pentecostal Church in Youhanabad, a massive Christian slum in southern Lahore. His family shifted to Youhanabad when he was a child. “We used to live in Jamshair Kalan village in Kasur but we got no respect there. People of the majority faith in many instances would not even like to eat with us,” he says.

The Christians also could not have businesses of their own in the village, he adds. All his six brothers and their families now live in Youhanabad. “Everyone around here is our coreligionist.”

Willy Van den Broucke, known as Father Henri, a Belgian missionary, set up Youhanabad and Bahar Colony in Lahore in the 1960s. These settlements offered Punjabi Christians land that was heavily subsidised by the church, discrimination-free social and business environment and Church-provided civic amenities such as education. Francisabad, a Christian village in Gujranwala, came about in 1978, also through the efforts of foreign missionaries, with the same objectives.

Derek Misquita, one of the six members of the religious minorities elected on reserved seats to the National Assembly in 1977, set up Derekabad along the same lines. During Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s government, the slogans of “roti, kapra aur makan” (food, clothing and housing for everyone) were ubiquitous. Misquita had close ties with Bhutto who encouraged him to settle Christians from across Pakistan in Thal desert, in the west of Punjab, as a way to realise those slogans. “We started coming to Derekabad around 1975,” says Sardar Masih, 76, a local resident. “The land was completely barren. We did not have even charpoys. We made makeshift houses of tents and dug trenches and filled them with water so that no scorpions, snakes or other venomous insects bite us. At night, we lit up fire to keep prey animals away.”

Like everywhere in Pakistan, most Christians living in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa have Punjabi origins.

Baba Lahoria, an 80-year-old resident of Derekabad, came here with the hope of getting farmland for his family. “It was a jungle. We levelled mounds and irrigated the land, employing camels to fetch water.”

Sardar Masih explains the rationale for shifting to such an inhospitable place: in villages in Punjab, “We used to work as saipis and in cities we could find work only as sanitary workers”. It always looked tempting, according to him, to try settling in a place where they could get farmland of their own. That dream has not materialised — not so far, in any case.

Close to 40 years after coming to Derekabad, Sardar Masih, Baba Lahoria and thousands of others living with them still do not formally own the farmland here in spite of a generally sympathetic judiciary and occasional administrative orders issued in their favour. “Now that the land has been made cultivable, local influential people are steadily snatching it from us with the help of the revenue department,” says Sardar Masih.

It is necessary to identify the fact that most katchi abadis [in Islamabad] are under the occupation of the Christian community, read a late 2015 letter by the Capital Development Authority (CDA), submitted to the Supreme Court that was hearing a case against the eviction of slum dwellers from the federal capital. These slums are destroying the look of Islamabad’s many residential sectors, making them resemble ugly villages, the letter noted before hitting out at the non-Muslim residents of the slums. “[The Christians] have shifted from Narowal, Sheikhupura, Shakargarh, Sialkot, Kasur, Sahiwal and Faisalabad and occupied the government land so boldly as if it has been allotted to them,” it pointed out. Then it went on to make its most strident observation: “This pace of occupation of land may affect the Muslim majority of the capital.”

The letter sounds as if Christians have launched a clandestine invasion of Islamabad and, secretly but steadily, they are working towards occupying it, one slum at a time. Yet, when the CDA finally demolished hundreds of homes in katchi abadis, none of them were found to be inhabited by Christians. And there was little to no resistance against the demolition — especially none from Christians.

In another part of the federal capital, life has been easier for Christians. Their abode, Francis Colony – a warren of low-slung mud houses built on the banks of a drain near F-7/4 sector – was recongnised as legal settlement back in 1988 when Benazir Bhutto first became prime minister. “We are better off here than we were in the village where we were treated as untouchables,” says Iqbal Masih, a paralysed resident of Francis Colony. He shifted to Islamabad from his village Charwind, in Sialkot district, as a young man in his twenties, to work in the construction sector in the new capital that was then being built.

It happened in Ramzan in 2012, recalls Haroon Mairaj, a resident of Karachi’s Essa Nagri area. Essa Nagri is a cluster of multi-storey shacks built to accommodate more than 20, 000 Christians of Punjabi origin in a cramped space of merely 20 acres or so. The city was undergoing a lot of tumult then, with various political parties and their militant wings competing for control of the streets. Crime was on the rise. Essa Nagri, wedged between Lyari Expressway in the west and University Road in the east, was being particularly targeted by thieves and bandits. Businesses were routinely attacked with demands for extortion and Christian women living in the neighbourhood were frequently harassed. Men from a neighbouring colony would flash torch lights on women sleeping outside their homes. All of this was followed by a string of targeted killings. Five men were murdered in a span of just two weeks. “We had just buried one body when more followed,” says Mairaj.

Residents of Essa Nagri decided to guard the area at night. One night, a patrol party spotted two men passing through the neighbourhood an hour or so before dawn. They looked suspicious and were asked to explain their presence in Essa Nagri. A scuffle ensued and Christian men beat up the two men.

Mairaj and some others residents of the neighbourhood then called the police. That started a series of unexpected events. “The police turned on us,” Mairaj recalls.

The two injured men alleged that the Christians had forced alcohol into their mouths during the fasting month of Ramzan. A criminal issue became a religious one, says Mairaj. “There was a jirga to settle the case,” he says. “Can you imagine? In this city, in this century, we had to partake in a jirga?”

The jirga asked local Christians to pay 100,000 rupees and two goats in compensation to the men the patrol party had manhandled. Essa Nagri’s residents collected the money and handed it over to the other side — mostly out of fear. “They said our lives were spared because of the month of Ramzan,” Mairaj reveals.

Essa Nagri, wedged between Lyari Expressway in the west and University Road in the east, was being particularly targeted by thieves and bandits.

Today Essa Nagri is fenced behind a 13-feet high boundary wall, partly custom-built, partly consisting of existing barriers. Residents of the neighbourhood mention the sense of security they have been feeling since the boundary was built in September 2012. Its construction started at 10pm and finished by 7am. “Overnight, we cordoned ourselves off,” Mairaj says. That, however, did not address all their existing and potential problems.

About eight Muslim households living within Essa Nagri soon started complaining about the boundary wall. They needed easier exit points to get to the mosque and madrasas. After much haggling and argumentation, the Christians were forced into constructing three gates — rendering the boundary wall less effective and letting the old fears of crime and violence rebound and escalate.

Hamida Begum was born in 1946 in Gujranwala. She moved to Karachi soon after marriage and worked as a midwife. “There was a lot of poverty in Punjab,” she says. Like most Punjabi Christians, her family worked in the fields. “If you did not want to work, they would take you away, anyway,” she says.

Her family’s travails, however, continued in Karachi. “My father worked at a toffee company here and he spent all his money on alcohol,” she says. In 2012, the police picked up her son, Nasir, along with another young man, suspecting them to be criminals. (Such arrests are a routine, say many local residents.) “We haven’t had a day of peace in this city.”

Essa Nagri’s history is as turbulent as Hamida Begum’s life. The neighbourhood has suffered some serious incidents of violence. In 1975, some Christians living here were accused of blasphemy. A local council was formed to deter violence but Muslims opened fire on Christians on the day the council was to meet. That was May 5, 1975. Three Essa Nagri men – Bashir, Khursheed and Gulzar – were killed and many others were injured.

Aziz Fazal was one of the injured. “I am a dead man walking,” he says as he points to a depression in his forehead. On that fateful day, a bullet scraped through his forehead.

Born in 1932 in Gujranwala, Fazal migrated to Karachi in 1947 to get away from the oppressive working conditions and lack of economic opportunities back in Punjab. A skeleton of a man with a propensity for exaggeration, he animatedly talks about how he was brought back to life by the grace of God.

He represents the first generation of Essa Nagri residents — mostly illiterate and unskilled. Many younger Christians here are either studying or working in health and social-work sectors. They speak fluent English and are politically and culturally aware. They are also conscious of how the rest of the society views them. “ ... these are the chuhras of Pakistan,” says a local young men, mocking the way others Karachiites refer to the residents of Essa Nagri.

The boys here are also disgruntled. Water supply and sanitation are very poor in their area. There is a lack of quality education – a government school built recently is completely abandoned – and there is widespread discrimination in school admissions and job interviews. “Hundreds of Christians work at the Aga Khan Hospital. Perhaps only one of them is on a managerial position. It is not as if they are not capable or qualified,” a bespectacled boy says.

Hanif Masih, a member of the older generation of Essa Nagri residents, is as bitter as the boys here are frustrated. “We did not get anything from Pakistan: no land, nothing. We do not get any rights or liberties. People from Afghanistan come here and prosper but we – Pakistanis, sons of the soil – have been neglected.”

Though he thinks Karachi has afforded people from his community a better economic life, he is extremely upset at the lack f security for Christians in Pakistan. A young man, silently listening to the conversation, adds: “Punjab is no good. Karachi is no good. Punjab main bhattay main maartay hain, Karachi main bori main dafnatay hain (in Punjab, they kill us in brick kilns; in Karachi they dump us, dead, in gunny bags).”

This article was originally published in the Herald's September 2016 issue under the headline "Caste away". To read more subscribe to the Herald in print.

Asif Aqeel is currently pursuing his MPhil in public policy and governance from Forman Christian College in Lahore.

Sama Faruqi is a former staffer of the Herald.