In a variety of Islamic political contexts around the world today, we see ‘Sufi’ ideas being invoked as a call to return to a deeper, more inward-directed (and more peaceful) mode of religious experience as compared to the one that results in outward-oriented political engagements that are often seen as negative and violent. A hundred years ago, it would not have been uncommon to hear western or West-influenced native voices condemn Islamic mysticism (often described problematically in English as ‘Sufism’) as one of the major sources of inertia and passivity within Muslim societies. Yet new political contingencies, especially after 9/11, have led to this same phenomenon being described as ‘the soft face of Islam’, with observers such as British writer William Dalrymple referring to a vaguely defined group of people called ‘the Sufis’ as ‘our’ best friends vis-à-vis the danger posed by Taliban-like forces.

We seem to be in a situation where journalistic discourse and policy debates celebrate idealised notions of Islamic mysticism with its enthralling music, inspiring poetry and the transformative/liberating potential of the ‘message’ of the great mystics. These mystics are clearly differentiated from more ‘closed-minded’ and ‘orthodox’ representatives of the faith such as preachers (mullahs), theologians (fuqaha) and other types of ulema.

On the other hand, when we trace the institutional legacy of these great mystics (walis/shaikhs) and spiritual guides (pirs) down to their present-day spiritual heirs, we find out that they are often all too well-entrenched in the social and political status quo. The degree of their sociopolitical influence has even become electorally quantifiable since the introduction of parliamentary institutions during colonial times. Pirs in Pakistan have been visible as powerful party leaders (Pir Pagara), ministers (Shah Mahmood Qureshi) and even prime ministers (Yousaf Raza Gillani). Even more traditional religious figures, such as Pir Hameeduddin Sialvi (who recently enjoyed media attention for threatening to withdraw support from the ruling party over a religious issue that unites many types of religious leaders), not only exercise considerable indirect influence over the vote but have also served as members of various legislative forums.

It is, therefore, unclear what policymakers mean when they call for investment in the concepts and traditions of ‘Sufi Islam’. Is it an appeal for the promotion of a particular kind of religious ethic through the public education system? Or is it a call for raising the public profile of little known faqirs and dervishes and for strengthening the position of existing sajjada-nishins (hereditary representatives of pirs and mystics and the custodians of their shrines), many of whom already enjoy a high level of social and political prominence and influence? Or are policymakers referring to some notion of Islamic mysticism that has remained very much at the level of poetic utterance or philosophical discourse — that is, at the level of the ideal rather than at the level of reality as lived and experienced by Muslims over centuries?

The salience of idealised notions of Islamic mysticism in various policy circles today makes it interesting to examine the historical relations that mystic groups within Islamic societies have had with the ruling classes and the guardians of religious law. What has the typical relationship among kings, ulema and mystics been, for example, in regions such as Central Asia, Anatolia, Persia and Mughal India that fall in a shared Persianate cultural and intellectual zone? Has tasawwuf (Islamic mysticism) historically been a passive or apolitical force in society, or have prominent mystics engaged with politics and society in ways that are broadly comparable to the way other kinds of religious representatives have done so?

It is instructive to turn first to the life of an Islamic mystic who is perhaps more celebrated and widely recognised than any other: Maulana Jalaluddin Rumi (d. 1273). He lived in Konya in modern-day Turkey. The fame of his mystic verse has travelled far and wide, but what is less widely known is that he had received a thorough training in fiqh (Islamic law).

Historical accounts show that he had studied the Quran and fiqh at a very high level in some of the most famous madrasas in Aleppo and Damascus. Later, he served as a teacher of fiqh at several madrasas. In this, he appears to have followed his father who was a religious scholar at a princely court in Anatolia and taught at an institution that blended the functions of a madrasa and those of a khanqah, demonstrating how fluid the relationship between an Islamic law college and a mystic lodge could be in Islamic societies. Even madrasas built exclusively for training ulema have often been paired with khanqahs since centuries.

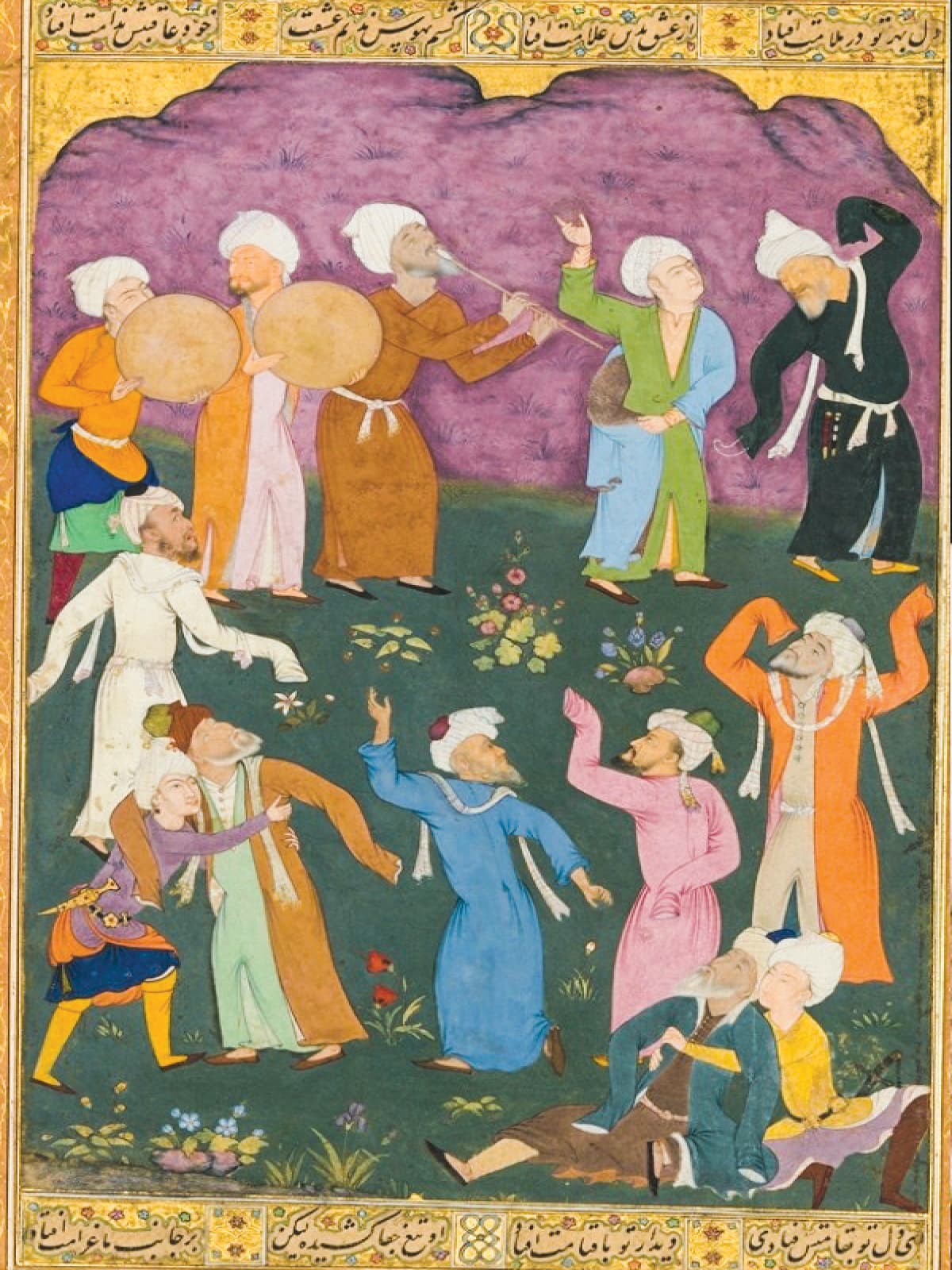

Biographers have described how Rumi’s legal opinions were frequently sought on a variety of subjects. As a spiritual guide and preacher, he regularly delivered the Friday sermon (khutba), achieving popularity as an acclaimed speaker and attracting a considerable number of disciples from all parts of society. His followers included merchants and artisans as well as members of the ruling class. His lectures were attended by both women and men in Konya. For much of this while, he was also composing his renowned poetry and becoming identified with his own style of sama’a and dance, which sometimes drew criticism from other ulema, many of whom nevertheless continued to revere him.

It is evident from Rumi’s letters that he also had extremely close relations with several Seljuk rulers, even referring to one of them as ‘son’. It was not rare for him to advise these rulers on various points of statesmanship and make recommendations (for instance, on relations with infidel powers) in light of religious strictures and political expediencies. He is also known to have written letters to introduce his disciples and relatives to men of position and influence who could help them professionally or socially. Unlike his religious sermons and ecstatic poetry, these letters follow the conventions typically associated with correspondence addressed to nobles and state officials.

All this contradicts the idea that mystics (mashaikh) are always firmly resistant to interacting with rulers. The stereotypical image of mystics is one where they are far too caught up in contemplation of the divine to have anything to do with the mundane political affairs of the world. Yet in sharp contrast to this image, many prominent mystics in Islamic history have played eminent roles in society and politics.

This holds true not only for the descendants of prominent mystics who continue to wield considerable sociopolitical influence in Muslim countries such as today’s Egypt and Pakistan but also for the mashaikh in whose names various mystical orders were originally founded. These mashaikh evidently lived very much in the world, not unlike nobles and kings and many classes of the ulema.

The offspring of these shaikhs also often became favoured marriage partners for royal princesses, thus becoming merged with the nobility itself.

Rumi’s life also offers evidence that the two worlds of khanqah and madrasa, often considered vastly different from each other, all too often overlap in terms of their functions. Regardless of the impressions created by mystic poetry’s derogatory allusions to the zahid (zealous ascetic), wa‘iz (preacher) or shaikh (learned religious scholar), there is little practical reason to see mystics on the whole as being fundamentally opposed to other leaders and representatives of religion. In fact, right through until modern times, we have seen ulema and mashaikh work in tandem with each other in the pursuit of shared religio-political objectives, the Khilafat movement in British India being just one such example among many of their collaborations.

Rumi’s activities are indicative of a nearly ubiquitous pattern of political involvement by prominent mystics in various Islamic societies. In Central Asia, support from the mashaikh of the Naqshbandi mystical order (tariqa) seems to have become almost indispensable by the end of the 15th century for anyone aspiring to rule since the order had acquired deep roots within the population at large. The attachment of Timurid and Mughal rulers to the Naqshbandi order is well known. The Shaybanid rulers of Uzbek origin also had deep ties with the order and Naqshbandi mashaikh tended to play a prominent role in mediating between Mughal and Uzbek rulers.

Naqshbandis are somewhat unusual among Sufi orders in their historical inclination towards involving themselves in political affairs, and for favouring fellowship (suhbat) over seclusion (khalwat), yet political interventions are not rare even among other orders.

Closer to home, Shaikh Bahauddin Zakariya (d. 1262), a Suhrawardi mystic, is reported to have negotiated the peaceful surrender of Multan to the Mongols, giving 10,000 dinars in cash to the invading army’s commander in return for securing the lives and properties of the citizens. Suhrawardis, indeed, have long believed in making attempts to influence rulers to take religiously correct decisions. Bahauddin Zakariya was very close to Sultan Iltutmish of the Slave Dynasty of Delhi and was given the official post of Shaikhul Islam. He openly sided with the sultan when Nasiruddin Qabacha, the governor of Multan, conspired to overthrow him.

It is widely known that the Mughal king Jahangir was named after Shaikh Salim Chishti (d. 1572) but what is less well known is that his great-grandfather Babar’s name ‘Zahiruddin Muhammad’ was chosen by Naqshbandi shaikh Khwaja Ubaidullah Ahrar (d. 1490), who wielded tremendous political power in Central Asia. The shaikh’s son later asked Babar to defend Samarkand against the Uzbeks. When Babar fell ill in India many years later, he versified one of Khwaja Ahrar’s works in order to earn the shaikh’s blessings for his recovery.

Even after Babar lost control of his Central Asian homeland and India became his new dominion, he and his descendants maintained strong ties with Central Asian Naqshbandi orders such as Ahrars, Juybaris and Dahbidis. This affiliation was not limited to the spiritual level. It also translated into important military and administrative posts at the Mughal court being awarded to generations of descendants of Naqshbandi shaikhs.

The offspring of these shaikhs also often became favoured marriage partners for royal princesses, thus becoming merged with the nobility itself. One of Babar’s daughters as well as one of Humayun’s was given in marriage to the descendants of Naqshbandi shaikhs. The two emperors also married into the family of the shaikhs of Jam in Khurasan. Akbar’s mother, Hamida Banu (Maryam Makani), was descended from the renowned shaikh Ahmad-e-Jam (d. 1141).

In India, Mughal princes and kings also established important relationships with several other mystical orders such as the Chishtis and Qadris. In particular, the Shattari order (that originated in Persia) grew to have significant influence over certain Mughal kings. It seems to have been a common tendency among members of the Mughal household to pen hagiographical tributes to their spiritual guides. Dara Shikoh, for example, wrote tazkirahs (biographies) of his spiritual guide Mian Mir (d. 1635) and other Qadri shaikhs. His sister Jahanara wrote about the Chishti shaikhs of Delhi.

So great was the royal reverence for mystics that several Mughal emperors, like their counterparts outside India, wanted to be buried beside the graves of prominent shaikhs. Aurangzeb, for example, was buried beside a Chishti shaikh, Zainuddin Shirazi (d. 1369). Muhammad Shah’s grave in Delhi is near that of another Chishti shaikh, Nizamuddin Auliya (d. 1325).

Like several other Mughal and Islamic rulers, Aurangzeb’s life demonstrates a devotion to a number of different mystical orders (Chishtis, Shattaris and Naqshbandis) at various points in his life. The emperor is reported to have sought the blessings of Naqshbandis during his war of succession with his brother Dara Shikoh. Naqshbandi representatives not only committed themselves to stay by his side in the battle but they also vowed to visit Baghdad to pray at the tomb of Ghaus-e-Azam Abdul Qadir Jilani (d. 1166) for his victory. They similarly promised to mobilise the blessings of the ulema and mashaikh living in the holy city of Makkah in his favour.

The combined spiritual and temporal power of influential mashaikh across various Islamic societies meant that rulers were eager to seek their political support and spiritual blessings for the stability and longevity of their rule. Benefits accrued to both sides. The mashaikh’s approval and support bolstered the rulers’ political position, and financial patronage by rulers and wealthy nobles, in turn, served to strengthen the social and economic position of mashaikh who often grew to be powerful landowners. The estates and dynasties left behind by these shaikhs frequently outlasted those of their royal patrons.

This is not to say that every prominent mystic had equally intimate ties with rulers. Some mashaikh (particularly among Chishtis) are famous for refusing to meet kings and insisting on remaining aloof from the temptations of worldly power. Shaikh Nizamuddin Auliya’s response to Alauddin Khilji’s repeated requests for an audience is well known: “My house has two doors. If the Sultan enters by one, I will make my exit by the other.” In effect, however, even these avowedly aloof mashaikh often benefited from access to the corridors of royal power via their disciples among the royal household and high state officials.

The relationship between sultans and mashaikh was also by no means always smooth. From time to time, there was a real breakdown in their ties. Shaikhs faced the prospect of being exiled, imprisoned or even executed if their words or actions threatened public order or if they appeared to be in a position to take over the throne. The example of Shaikh Ahmad Sirhindi (d. 1624) is famous. He was imprisoned by Jahangir for a brief period reportedly because his disquietingly elevated claims about his own spiritual rank threatened to disrupt public order. Several centuries earlier, Sidi Maula was executed by Jalaluddin Khilji, who suspected the shaikh of conspiring to seize his throne.

It is not only through influence over kings and statesmen that Islamic mystical orders have historically played a political role. Some of them are known to have launched direct military campaigns. Contrary to a general notion in contemporary popular discourse that ‘Sufism’ somehow automatically means ‘peace’, some Islamic mystical orders have had considerable military recruiting potential.

The Safaviyya mystical order of Ardabil in modern day Iranian Azerbaijan offers a prominent example of this. Over the space of almost two centuries, this originally Sunni mystical order transformed itself into a fighting force. With the help of his army of Qizilbash disciples, the first Safavid ruler Shah Ismail I established an enduring Shia empire in 16th century Iran.

In modern times, Pir Pagara’s Hurs in Sindh during the British period offer another example of a pir’s devotees becoming a trained fighting force. It is not difficult to find other examples in Islamic history of mashaikh who urged sultans to wage wars, accompanied sultans on military expeditions and inspired their disciples to fight in the armies of favoured rulers. Some are believed to have personally participated in armed warfare.

To speak of a persistent difference between the positions of ulema and mystics on the issue of war or jihad would be, thus, a clear mistake. ‘Sufism’ on the whole is hardly outside the mainstream of normative Islam on this issue, as on others.

Another popular misconception is to speak of ‘Sufism’ as something peculiar to the South Asian experience of Islam or deem it to be some indigenously developed, soft ‘variant’ of Islam that is different from the ‘harder’ forms of the religion prevalent elsewhere. Rituals associated with piri-muridi (master-disciple) relationships and visits to dargahs can, indeed, display the influence of local culture and differ significantly from mystical rituals in other countries and regions.

However, the main trends and features defining Islamic mysticism in South Asia remain pointedly similar to those characterising Islamic mysticism in the Middle East and Central Asia. As British scholar Nile Green points out, “What is often seen as being in some way a typically South Asian characteristic of Islam – the emphasis on a cult of Sufi shrines – was in fact one of the key practices and institutions of a wider Islamic cultural system to be introduced to South Asia at an early period ... It is difficult to understand the history of Sufism in South Asia without reference to the several lengthy and distinct patterns of immigration into South Asia of holy men from different regions of the wider Muslim world, chiefly from Arabia, the fertile crescent, Iran and Central Asia.”

It is a fact that all the major mystical orders in South Asia have their origins outside this region. Even the Chishti order, which has come to be associated more closely with South Asia than with any other region, originated in Chisht near Herat in modern-day Afghanistan. These interregional connections have consistently been noted and celebrated by masters and disciples connected with mystic orders over time. Shaikh Ali al-Hujweri (d. circa 1072-77), who migrated from Ghazna in Afghanistan to settle in Lahore, is known and revered as Data Ganj Bakhsh. Yet this does not mean that the status of high ranking shaikhs who lived far away from the Subcontinent is lower than his in any way. Even today, the cult of Ghaus-e-Azam of Baghdad continues to be popular in South Asia.

The third myth is that mystics across the board are intrinsically ‘peaceful’ and opposed to armed jihad or warfare.

For anyone who has the slightest acquaintance with Muslim history outside the Subcontinent, it would be difficult to defend the assertion – one that we hear astoundingly often in both lay and academic settings in South Asia – that ‘Sufi Islam’ is somehow particular to Sindh or Punjab in specific or to the Indian subcontinent more broadly. It is simply not possible to understand the various strands of Islamic mysticism in our region without reference to their continual interactions with the broader Islamic world.

What is mystical experience, after all? The renowned Iranian scholar Abdolhossein Zarrinkoub defines it as an “attempt to attain direct and personal communication with the godhead” and argues that mysticism is as old as humanity itself and cannot be confined to any race or religion.

It would, therefore, be quite puzzling if Islamic mysticism had flowered only in the Indian subcontinent and in no other Muslim region, as some of our intellectuals seem to assert. Islamic mysticism in South Asia owes as much to influences from Persia, Central Asia and the Arab lands as do most other aspects of Islam in our region. These influences are impossible to ignore when we study the lives and works of the mystics themselves.

As Shaikh Ahmad Sirhindi (Mujaddid-e-Alf-e-Sani) wrote in the 16th-17th century: “We ... Muslims of India ... are so much indebted to the ulema and Sufis (mashaikh) of Transoxiana (Mawara un-Nahr) that it cannot be conveyed in words. It was the ulema of the region who strove to correct the beliefs [of Muslims] to make them consistent with the sound beliefs and opinions of the followers of the Prophet’s tradition and the community (Ahl-e-Sunna wa’l-Jama’a). It was they who reformed the religious practices [of the Muslims] according to Hanafi law. The travels of the great Sufis (may their graves be hallowed) on the path of this sublime Sufi order have been introduced to India by this blessed region.” *

These influences were not entirely one-way. We see that the Mujaddidi order (developed in India by Shaikh Ahmad Sirhindi as an offshoot of the Naqshbandi order) went on to exert a considerable influence in Central Asia and Anatolia. This demonstrates once again how interconnected these regions had been at the intellectual, literary and commercial levels before the advent of colonialism.

This essay has been an attempt to dispel four myths about Islamic mysticism. The first myth is that there is a wide gap between the activities of the mystic khanqah and those of the scholarly madrasa (and that there is, thus, a vast difference between ‘Sufi’ Islam and normative/mainstream Sunni Islam). The second myth is that mystics are ‘passive’, apolitical and withdrawn from the political affairs of their time. The third myth is that mystics across the board are intrinsically ‘peaceful’ and opposed to armed jihad or warfare. The last myth is that Islamic mysticism is a phenomenon particular to, or intrinsically more suited to, the South Asian environment as compared to other Islamic lands.

All these four points are worth taking into consideration in any meaningful policy discussion of the limits and possibilities of harnessing Islamic mysticism for political interventions in Muslim societies such as today’s Pakistan. It is important to be conscious of the fact that when we make an argument for promoting mystical Islam in this region, we are in effect making an argument for the promotion of mainstream Sunni (mostly Hanafi) Islam in its historically normative form.

**Translation by Dr Sajida Alvi*

The writer is a doctoral student in Mughal history at the Institute of Islamic Studies at McGill University in Canada.

This was originally published in the April 2018 issue of the Herald. To read more subscribe to the Herald in print.