This essay must start with a qualification: it offers only a selective overview of developments in modern and contemporary art in Pakistan. Here, the term ‘modern’ is used for the art produced between the middle of the 20th century and the beginning of 1990s; after that ‘contemporary’ art comes into vogue. Modernism largely avoids engagement with the immediate and the present.

Rather than focusing on specific social circumstances or engaging with current events, modern art offers metaphoric and transcendent alternatives to the real world. Its materials and mediums seek permanence. By contrast, contemporary art is immersed in the immediate and the present. Unlike modernism, it offers no transcendence but instead engages with existing conditions. It is often ‘post-medium’ as ‘contemporary’ artists usually employ diverse materials and techniques that include ephemeral and time-based mediums.

Abdur Rahman Chughtai (1894–1975) enjoyed a long and productive career and stands out as the first prominent modern Indian Muslim artist. He studied at the Mayo School of Art in Lahore circa 1911 and began painting early in his life. He forged a distinctive style and grounded his art in the ideas of Urdu writers and poets. By the 1920s, under the influence of poet Muhammad Iqbal’s pan-Islamic ideas, he started basing his paintings on consciously Islamic and Mughal aesthetics. His influential publication – Muraqqa’-i Chughtai (published in 1928) that illustrates the poetry of Mirza Ghalib – marks this shift. Chughtai and Iqbal possessed a cosmopolitan Muslim imagination during the first half of the 20th century when independent nation states in South Asia and much of the Middle East had not yet materialised. But while Iqbal’s later poetry and philosophy is characterised by dynamism, Chughtai’s artistic ethos is marked by introspective stasis. His early paintings are set outdoors or in simple architectural frames, illustrating Hindu mythological figures. By contrast, his later paintings are set in arabesque interiors in which female figures are covered in elaborate, stylised layers of clothing. These paintings are not based on a particular narrative but create an aesthetic universe akin to the one conjured by classical Urdu ghazal.

Chughtai was over 50 years old in 1947 but, while he remained an admired figure, he had no prominent disciples in the newly created Pakistan who would follow in his artistic footsteps. Pakistani art needed a new formal language that could better express the challenges of mid-century modernity and decolonisation. For a fully modernist artistic practice to emerge, Pakistan also needed a restructuring of its art schools and exhibition venues since a large number of art teachers, students and curators had left for India after Partition.

At the time of its creation, the country faced a difficult landscape for fine arts. Even Lahore – that at the time had two schools for art instruction, the Mayo School of Art and the Department of Fine Arts at the Punjab University – was in a poor shape because of the departure of many art instructors and students. Karachi virtually had no art scene before 1947 and there was not a single art school in East Pakistan.

Key institutional developments took place over the next two decades. The Mayo School of Art was upgraded to the National College of Arts (NCA) in 1958, a move that facilitated a greater focus on the teaching of modern art. During the tenure of Shakir Ali (1916–1975) – first as an instructor in painting from 1952 to 1961 and then as principal from 1961 to 1969 – NCA became an incubator of modernism in West Pakistan. At the Punjab University, expressionist painter Anna Molka Ahmed (1917–1995) became the head of the Department of Fine Arts and held the post for many years, organising numerous exhibitions during the 1950s and publishing many catalogues on emerging artists. In Dhaka, Zainul Abedin (1914–1976) founded the influential Institute of Fine Arts in 1948. Artistic societies and arts councils emerged in many cities. These included the Arts Council in Karachi, the Alhamra Arts Council in Lahore and the Gallery of Contemporary Art in Rawalpindi that artist Zubeida Agha (1922–1997) headed for 16 years beginning in 1961. When scholar and historian Aziz Ahmad noted in 1965 that the “Westernized elite of Pakistan takes its modern art seriously”, he was also commenting on the evolving reception of modern art in the country over the previous 17 years.

Zainul Abedin, one of the best-known artists at the birth of Pakistan, played a key role in promoting art across the country, especially in East Pakistan. He studied painting at the Government School of Art in Calcutta from 1933 to 1938 and then taught there until 1947 before moving to Dhaka. His work first attracted public attention in 1943 when he produced a powerful series of drawings on the famine in Bengal. As the founder principal of Dhaka’s Institute of Fine Arts, he soon turned it into the best art school in Pakistan. Not only was his art practice exemplary for his students, he was also respected for his administrative skills which he judiciously exercised to promote art and crafts in both wings of the country. After Bangladesh’s independence in 1971, he came to be regarded as the founding figure of modern Bangladeshi art.

His practice was divided between modernist experimentation and depiction of folk and tribal elements in East Bengal’s culture. As Badruddin Jahangir has pointed out, Zainul Abedin avoided painting “pictures of Muslim glory” like Chughtai did. He, instead, portrayed peasants and bulls from rural Bengal. Human beings and animals in his work appear as labouring bodies and heroic figures engaged in struggle. He also recognised the need to create a rooted modern high culture because the Bengali bhadralok (middle class) high culture of those times was seen as Hindu culture and was thus disapproved of by the West Pakistani ideologues. He argued for and practised a “Bengali modernism” based on folk themes, abstracting them into motifs characterised by rhythm and arrangement of colour and pattern.

Other artists from East Pakistan active during 1950s and 1960s include Quamrul Hassan (1921-1988), SM Sultan (1923–1994), Hamidur Rahman (1928–1988), Mohammad Kibria (1929-2011), Aminul Islam (1931-2011) and the pioneering modernist sculptor Novera Ahmed (1939-2015). A lively artistic exchange then flourished between the eastern and western wing of the country despite political tensions. Exhibitions in one wing featured works from the other wing and artists travelled frequently between the two parts of Pakistan.

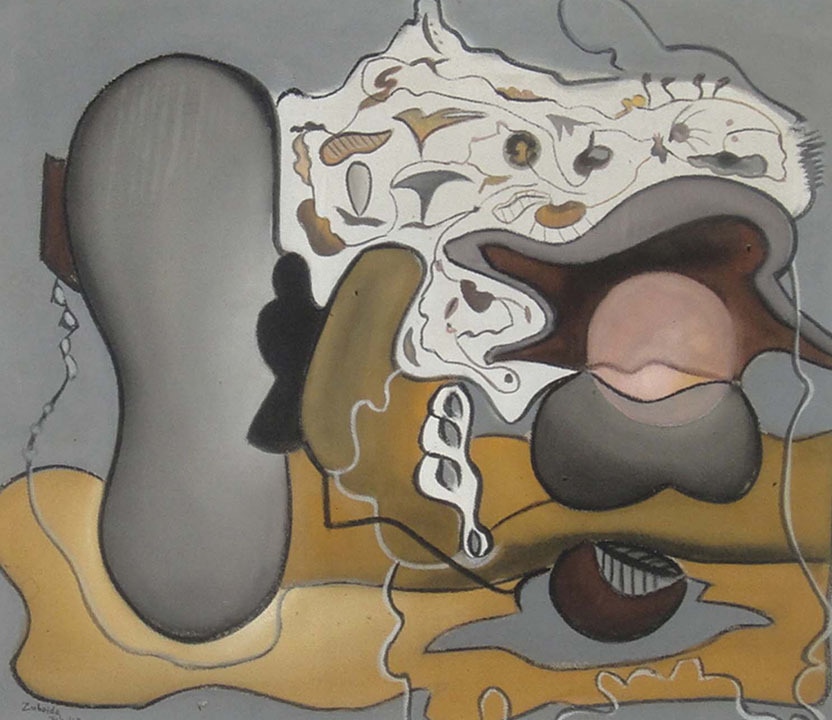

Zubeida Agha’s solo exhibition of provocative “ultra-modern” paintings in 1949 “fired the first shot”, as noted a critic who marked it as a key event in the emergence of modernism in the country. She was Pakistan’s first properly modernist painter. Her enlightened family had encouraged her early interest in art in the 1940s. She was deeply struck by the modernist painter Amrita Sher-Gil (1913–1941) who had died young in Lahore and whose unconventional life and art have become the stuff of legend. Apart from her work as the director of Rawalpindi’s Gallery of Contemporary Art, Zubeida Agha was involved in discussions and plans for setting up a national art gallery and a national art collection.

She led a mostly reclusive life. Her engagement with modernism was a focused, lifelong endeavour, forged through her study of Greek philosophy, classical Western music and mysticism as well as her fascination with the urban. Her later paintings move between depiction and abstraction and are characterised above all by decorative motifs in dazzling colours. Yet the very richness and surfeit of her ornamental aesthetic create a modernist effect — of a reflexive alienation. Unlike the flattened picture plane of Chughtai’s watercolours, her “third dimension” is seen as a modernist artistic structure in which the dynamism and balance of elements express ideas, tonalities and moods.

Ahmed Parvez (1926–1979), who spent a decade in the United Kingdom starting from 1955 before returning to Pakistan, also developed a dynamic language of colourist abstractions. In contrast with the contemplative compositions of Zubeida Agha’s work, however, his explosive forms mirror his volatile existential dilemmas.

The decades immediately after independence saw important political developments take place that would come to shape modern Pakistani art. Soon after, Pakistan’s founding, military-bureaucratic-industrial establishment concentrated in the western part of the country started following unwise policies that alienated East Pakistan. As a Cold War ally of the United States, Pakistan also suppressed leftist intellectuals and activists. But repression alone cannot fully explain why Pakistani artists disavowed realism and adopted modernism. A major reason was that modernism helped them express subjective and social predicaments in a more complex manner than was possible through realism.

Some early modernists such as Shakir Ali were also leftist political activists. He began his artistic training in 1937 in Delhi and joined the J. J. School of Art in Bombay in 1938 as a student. By then he was also contributing progressive Urdu texts to literary journals. He later studied and worked in London, France and Prague for many years. There he was associated with socialist youth groups. His mentoring and personality were decisive in inspiring a generation of students and fellow artists who emerged on the art scene between the 1950s and 1970s. These include figurative cubist painter Ali Imam (1924–2002), Anwar Jalal Shemza (1929–1985) and Zahoor ul Akhlaq (1941–1999).

Shakir Ali’s modernism was restrained and disciplined. He focused his work on exploring form and composition rather than on narrative and drama. Birds, cages, moon and flowers became symbols in his paintings for human finitude and its transcendence through imagination. He remained immune to jingoistic motivations as is clear from his refusal to assume a nationalist stance during the 1965 war between India and Pakistan. Indeed, the lives of Zubeida Agha, Shakir Ali and many key artists of the generation that followed them, including that of Zahoor ul Akhlaq, are marked by an enigmatic silence on many issues of public importance. Their works were giving shape to an artistic project aimed at exploring visual allegories for ethical and social dilemmas more deeply than was possible through public debate in that era.

During the 1960s and 1970s, calligraphic modernism formed an increasingly influential mode of expression though Hanif Ramay (1930–2006) had started reformulating calligraphy to express abstract ideas as early as the 1950s. Iqbal Geoffrey (born in 1939) developed an expressionist calligraphic practice, accompanied by a playful Dadaist performative persona, during his stay in the United Kingdom and the United States in the 1960s. Anwar Jalal Shemza, who was also a noted Urdu writer, moved to the United Kingdom during the mid-1950s and developed an important body of abstract calligraphic work. Inspired by Swiss-German artist Paul Klee, Arabic calligraphy and carpet designs – his family had earlier been involved in the carpet business – he worked out his aesthetic mode of expression over the course of a disciplined career. His Roots series, executed in the mid-1980s towards the end of his life, exhibits remarkable formal restraint as it expresses the anguish of an expatriate. Jamil Naqsh (born in 1938 and now based in London) has also created numerous abstract calligraphic paintings apart from his signature figurative oeuvre.

But the greatest practitioner of calligraphic modernism is Pakistan’s most celebrated artist Sadequain (1930–1987). His rise to extraordinary fame commenced in 1955 when he exhibited his works in Karachi with the support of Prime Minister Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, a liberal patron of arts. Sadequain soon received many prestigious government commissions. A large number of murals he executed between 1957 and his death have reinforced his myth as a suffering but heroic artist. His gigantic 1967 mural at Mangla Dam, titled The Saga of Labour, is based on Iqbal’s poetry and celebrates humanity’s progress through labour and modernisation.

During a residency at Gadani near Karachi in the late 1950s, Sadequain encountered large cactus plants whose vertical, leafless and prickly branches formed silhouettes suggestive of calligraphic forms. He subsequently moved towards an imagery that contained exaggerated linear features drawn like cactus plants. His self-portraits and murals evoke a sense of movement and dynamism that mark his most significant works of the late 1960s, including his 1968 paintings based on Ghalib’s poetry. His residence in Paris during the 1960s was also formative in his artistic development. A 1966 series of drawings he made in France depicts him in his studio with his severed head and in the company of female figures. The drawings associate Sadequain with transgressive Sufis such as Sarmad (whose head was cut off on the order of Mughal emperor Aurangzeb in 1661) and with Picasso’s drawings and prints from 1930s on the mythos of the artist and the model.

Sadequain charted a unique artistic trajectory. He remained close to the state that promoted calligraphy during the Islamisation of the 1970s and 1980s yet he exhibited aspects of transgressive Sufism through his persona. His star status also allowed him to address an audience wider than the urban elites. As Lahore-based artist Ijaz ul Hassan (born in 1940) has aptly noted: “[Sadequain] never hesitated to glorify the inherent strength and creative spirit of man, and his ability to build a better world … [He] was the first to have liberated painting from private homes and transformed it into a public art … ”

Other modernists have also broken new ground. Rasheed Araeen, who was born in Karachi in 1935 but moved to London in 1964, has been producing art based on constructivism and geometry while at the same time being active against racism and inequality. Race and inequality have formal value as well as social significance in his art. In 1987, he founded and began editing Third Text, a journal that offers an important global critical platform for writings on modern and contemporary art. In recent years, he has engaged more closely with artistic and intellectual developments in Pakistan.

Karachi-based artist Shahid Sajjad (1936-2014) was a pioneer sculptor in carved wood and cast metal. His work continues to influence subsequent practitioners of these genres across Pakistan. A R Nagori (1939-2011), who taught art at the Sindh University, Jamshoro, addressed marginalisation and inequality in expressionist paintings that depict symbolic facets of aboriginal communities in Sindh and the surreal excesses of General Ziaul Haq’s regime. Zahoor ul Akhlaq created drawings, paintings and sculpture that have left deep and formative impacts on numerous artists working today. And Imran Mir (1950-2014) was one of the first few to systematically investigate geometric forms in painting and sculpture.

Many of the latter-day modernists were still actively producing art during the 1990s even though modernism had begun to transition to contemporary art by then.

Contemporary art practices emerged in the context of specific political, economic and global developments: the rise of Islamist politics since the mid-1970s, the emergence of feminist activism during the 1980s, the restoration of an unstable democracy (in 1988-1999), the privatisation of state-owned businesses under direction from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, the accelerated growth of mega cities, the migrations of skilled and unskilled workers abroad in large numbers, the arrival of global satellite television in the early 1990s, the advent of Internet and liberalisation of media, and the impact of foreign artists, curators, biennials and residencies. As these developments stirred and agitated the artistic community in Pakistan, some artists found the formal and thematic framework employed by their modernist predecessors as inadequate. Pakistani art practice had been primarily easel-based oil or watercolour painting or sculpture till the early 1990s. Its formal modes were also focused on landscapes, calligraphic abstraction and regional, historical figures and symbols.

Contemporary artists wanted to address social concerns more directly than was possible with the languages of modernism. They were also intrigued by the artistic potential of new mediums and technologies. These motivations are evident in the work of artists who are making increasing forays into mediums previously marginal to art in Pakistan such as performance and video. Sculptor Amin Gulgee has created a regular platform to support performance art in Karachi. Hurmat Ul Ain and Rabbya Nasser have done a number of collaborative performances. Photography has matured as an important medium for artistic expression. While Arif Mahmood has pursued a subjective lyrical approach in his photos, Nashmia Haroon and Naila Mahmood have documented social and spatial inequities in their photography. Others such as Sajjad Ahmed, Aamir Habib, Amber Hammad, Aisha Abid Hussain, Sumaya Durrani, Anwar Saeed, Mohsin Shafi, Mahbub Shah, Zoya Siddiqui and Iqra Tanveer have extensively employed lens-based montage, staging, manipulation and conceptual approaches. Bani Abidi, Sophia Balagam, Yaminay Chaudhri, Ferwa Ibrahim, Haider Ali Jan, Ismet Khawaja, Mariah Lookman, Basir Mahmood, Sarah Mumtaz, Aroosa Rana, Fazal Rizvi and Shahzia Sikander have used video and new media as key modes for their artistic expression.

A representative selection of diverse contemporary artworks can be viewed in the catalogue of the Rising Tide exhibition curated by Naiza Khan in 2010 and in Salima Hashmi’s more recent book, The Eye Still Seeks: Pakistani Contemporary Art (published in 2015).

A major contributor to the growth of contemporary art is the evolution of an art school culture that has proliferated in recent decades. Many innovative contemporary artists today are either former students of the NCA, the Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture (IVS), Karachi, and the Beaconhouse National University (BNU), Lahore, or they are teachers at these institutions.

During the last few decades, faculty at the NCA has included such accomplished artists and art teachers as Bashir Ahmad, Naazish Ata-Ullah, Jamil Baloch, Colin David, Salima Hashmi, Muhammad Atif Khan, Afshar Malik, Quddus Mirza, R M Naeem, Imran Qureshi, Qudsia Rahim, Anwar Saeed, Nausheen Saeed and Beate Terfloth. While miniature painting had been taught at the NCA for decades, by the 1980s under encouragement by Zahoor ul Akhlaq — who was interested in the miniature’s underlying structure — its pedagogy converged with other aesthetic frameworks. The NCA has consequently produced notable New Miniature artists from the 1990s onwards. These include Waseem Ahmed, Khadim Ali, Ayesha Durrani, Irfan Hasan, Ahsan Jamal, Aisha Khalid, Hasnat Mehmood, Murad Khan Mumtaz, Imran Qureshi, Nusra Latif Qureshi, Wardha Shabbir, Madiha Sikander, Shahzia Sikander, Aakif Suri, Saira Wasim and Muhammad Zeeshan. Their work ranges from meticulously rendered figures and repeated floral and decorative motifs on vasli paper to unorthodox sculptures and large scale installations.

The other change brought about by the NCA is an expansion of artistic activity beyond the issues and concerns of big cities and the likes and dislikes of their elites. Being a state institution, it admits a diverse student body that cuts across rural and urban divides and other distinctions based on class, province and ethnicity. Many contemporary artists trained by the NCA come from different parts of Pakistan but they have made Lahore their home. A number of them – Noor Ali Chagani, Imran Channa, Shakila Haider, Ali Kazim, Waqas Khan, Nadia Khawaja, Rehana Mangi, Usman Saeed and Mohammad Ali Talpur – employ in their works a rigorous and repetitive mode of expression pioneered by Zahoor ul Akhlaq and the recently deceased former NCA teacher Lala Rukh (1948-2017). While Zahoor ul Akhlaq investigated the tension between geometry and narrative at a structural level, Lala Rukh was steadfastly committed to her spare, minimalist practice on diverse and unorthodox materials.

The simultaneous proliferation of art schools has also created a competitive environment in which teachers and students are more willing to experiment than ever before. The work of many BNU graduates employs innovative conceptual strategies and digital technologies. Salima Hashmi served as the founding dean of its School of Visual Arts & Design from 2003 till recently. Its faculty members have included David Alesworth, Unum Babar, Sophie Ernst, Malcolm Hutcheson, Samina Iqbal, Ghulam Mohammad, Huma Mulji, Rashid Rana, Ali Raza, Razia Sadik and Risham Syed.

The IVS, founded in 1989, has had a notable art faculty that includes Meher Afroz, Roohi Ahmed, David Alesworth, Elizabeth Dadi, Saba Iqbal, Naiza Khan, Naila Mahmood, Samina Mansuri, Asma Mundrawala, Nurayah Sheikh Nabi, Seher Naveed, Muzzumil Ruheel, Sadia Salim, Gemma Sharpe, Saira Sheikh, Adeela Suleman, Munawar Ali Syed, Omer Wasim and Muhammad Zeeshan. Its teachers and students experiment with diverse forms, structures and materials while focussing on Karachi’s complex urban issues such as identity, labour, infrastructure and public space. Established a decade after the IVS by artist Durriya Kazi, the Department of Visual Studies at the University of Karachi has also trained many active practitioners of contemporary art.

Some artists trained at these institutions have brought traditional mediums in conversation with diverse non-traditional materials and approaches. Akram Dost Baloch in Quetta and Abdul Jabbar Gull in Karachi, for instance, work with carved, constructed and relief sculptural works. Ehsan ul Haq, Mehreen Murtaza, Seema Nusrat and Ayesha Zulfiqar have made conceptual multimedia installations. Many others – such as Sana Arjumand and Jamal Shah in Islamabad, Numair Abbasi, Moeen Faruqi, Madiha Hyder, Rabeya Jalil, Unver Shafi and Adeel uz Zafar in Karachi and Rabia Ajaz, Nurjahan Akhlaq, Fahd Burki, Fatima Haider, Sehr Jalil, Ayaz Jokhio, Madyha Leghari, Zahid Mayo, Imran Mudassar, Abdullah Qureshi, Kiran Saleem and Inaam Zafar in Lahore – have been committed to drawing, painting and printmaking in abstract, expressionist, figurative and narrative modes.

Increased opportunities for higher education as well as residencies and workshops abroad have allowed artists to learn and practice new skills. Karachi-based Vasl Artists’ Collective (part of the Triangle Arts Network) has initiated important residency programmes since its founding in 2000. Recent ventures by Karachi’s Sanat Gallery and Saba Khan’s Murree Museum Artists Residency are also notable initiatives. The Lahore Biennale Foundation has supported a number of prominent and innovative public art projects. The move towards exhibitions curated around a theme – by such curators as Aasim Akhtar, Hajra Haider Karrar, Adnan Madani, Zarmeené Shah and Aziz Sohail among others – is another recent development that is prompting artists to explore new ways to create and showcase their works.

This does not mean that all is well and wonderful in Pakistan’s art scene. A major issue is the near-absence of rigorous exposure to the study of humanities, social sciences and critical theory. This ultimately limits the intellectual growth of art graduates. For example, many young artists continue to simply quote historical motifs and artistic fragments from the past in their compositions. Others replace original motifs in ancient works with contemporary images or juxtapose them with commodity visuals. Rarely are these attempts groundbreaking. They are symptomatic of an inadequate critical ability to meaningfully engage with the history of art — a necessary part of finding one’s path as an artist. A deeper understanding of Indic art, miniature painting and western art movements may offer students more fundamental lessons pertaining to scale, structure and finesse in formal terms (of which Zahoor ul Akhlaq serves as an earlier exemplar) as well as those concerning the social significance of such artistic concerns as patronage, circulation, address, narrative, history and economy. It does not help when graduating students triumphantly sell their work during degree shows. This reinforces the notion that market success is the primary measure of an artwork’s value rather than the process of research and investigation and the inevitably awkward initial grappling with complex aesthetic and social questions.

A related problem is the absence of robust platforms for intellectual debate. The few journals on art or culture that exist in Pakistan have been unable to frame key issues in ways that engender serious discussion. Even these journals have not been published regularly. Two of them – Sohbat published by the NCA and Nukta Art issued from Karachi – folded recently, leaving in their wake an even more impoverished discourse on art. Online journal ArtNow: Contemporary Art of Pakistan has thus assumed great significance as far as reviews and criticism of contemporary art in Pakistan are concerned.

This is partly addressed by graduate programmes at the NCA, led by Lala Rukh earlier and Farida Batool at present. The focus on the study of humanities at the undergraduate level at the recently founded Habib University in Karachi and the announcement of a new undergraduate cultural studies programme at the NCA offer grounds for optimism. A critical mass of engaged writers and theorists on art and culture may emerge in the years to come.

Democracy was restored in Pakistan in 1988 but it brought little relief to Karachi. Throughout the 1990s, the city had a severely depressed economy and experienced deadly violence between the government and identity-based political groups. But Karachi is also remarkable for its ever-proliferating commercial energy and its ceaselessly vibrant visual culture. The rise of popular urban aesthetics during the 1990s in the city needs to be situated against this background. Initiated by the art practices of David Alesworth, Elizabeth Dadi, myself and Durriya Kazi, this development is sometimes referred to as “Karachi Pop”. Its aesthetics bypass fidelity to national or folk authenticity and deploy informal urban objects and popular images to create photographs, sculpture and multi-media-based works that explore cinematic fantasy and everyday desire. Other artists who have similarly worked extensively with urban and media-popular cultures include Faiza Butt, Haider Ali Jan, Saba Khan, Ahmed Ali Manganhar, Huma Mulji, Rashid Rana and Adeela Suleman.

Many contemporary artists have worked on the complex ramifications of the post-9/11 era. Sensitive portraits of young madrasa students by Hamra Abbas in her work God Grows on Trees (2008), Rashid Rana’s digital photomontages that bring opposites together in perpetual tension and Imran Qureshi’s Moderate Enlightenment miniature paintings (2006-08) as well as his large scale installation at the Sharjah Biennial (2011) are among the most thoughtful works in this regard. 9/11, however, has also resulted in the production of many one-dimensional works that serve little purpose other than manifesting how global terrorism has eclipsed other important issues that contemporary art ought to have been investigating.

Feminism, too, has been a major theme in contemporary art. During the 1980s, feminist artists and poets emerged as the most vocal opponents of Zia’s Islamisation policies. Artists and activists Salima Hashmi and Lala Rukh have played a major role in this opposition. Since then many other artists have employed various modes of expression and genres to explore feminist themes and ideas. Naiza Khan’s art has explored the materiality of the female body since the early 1990s; Aisha Khalid’s paintings have investigated the liminal status of the female body trapped within decorative and ornamental motifs; Farida Batool’s photographic work critically locates the vulnerability of the ludic female body in urban space; Ayesha Jatoi has made striking interventions on public monuments that display military hardware; Adeela Suleman’s early work with decorated cooking utensils highlights the dangers women motorcycle riders face; Risham Syed has utilised embroidery and fabrics to highlight the disjunction between genteel domesticity and violence in public spaces; and Rabia Hassan’s videos draw attention to the rampant objectification of women’s bodies in Pakistani commercial cinema.

Globalisation’s impact on contemporary art has also been significant. It has reconfigured the relationship between home and diaspora through ease in foreign travel and developments in communication technologies. Home and diaspora now exist in much closer proximity than was the case in the past. Many Pakistani artists have migrated abroad but they are producing artworks on themes and subjects that directly or indirectly link them to their home country. One of the most prominent among these expatriates is Bani Abidi. She has lived in India and Germany but continues to tackle fraught issues of identity and everyday life in Pakistan. Huma Bhabha, who developed her career primarily in New York, has created a series of apocalyptic prints based on photographs from Karachi titled Reconstructions (2007) and Seher Shah (now based in India) has explored haunting afterimages of exposure to Mughal and British colonial imagery. Other artists living abroad include Mariam Suhail and Masooma Syed (both based in India), Mariah Lookman (who resides in Sri Lanka), Saira Ansari, Rajaa Khalid, Saba Qizilbash and Hasnat Mahmood (who live and work in the United Arab Emirates), Humaira Abid, Anila Qayyum Agha, Komail Aijazuddin, Ambreen Butt, Khalil Chishtee, Ruby Chishti, Simeen Farhat, Talha Rathore, Hiba Schahbaz, Shahzia Sikander, Salman Toor and Saira Wasim (all based in the United States), Farina Alam and Faiza Butt (based in London), Khadim Ali, Nusra Latif Qureshi and Abdullah M I Syed (who have lived in Australia) and Samina Mansuri, Tazeen Qayyum, Amin Rehman and Sumaira Tazeen (who have migrated to Canada).

A more direct engagement of art with the enormous issues of social justice in Pakistan is also developing amongst contemporary artists. By making site-specific interventions (instead of creating discrete art objects such as paintings and sculptures), some artist collectives are investigating social processes and relations in modes that venture beyond the dominant ways of artistic expression. The Awami Art Collective in Lahore has done projects in public spaces that critique sectarianism and destructive urban development. Karachi-based Tentative Collective has focused on making interventions in subaltern communities of the city. And the archival and research-based work by Zahra Malkani and Shahana Rajani analyses how large-scale inequality is being structurally entrenched on the physical and socioeconomic margins of Karachi.

This essay was completed before two major art events – the Karachi Biennale curated by Amin Gulgee and the Lahore Biennale – have transpired. One hopes and expects that these ventures will distinctively and positively transform the trajectory of contemporary art in Pakistan in the months and years to come.

Some of the experimental contemporary art work has been supported by Vasl, Gandhara-Art and the Lahore Biennale Foundation. But to continue to flourish, it urgently needs sustained and substantial support from state and private cultural organisations for research and production. It also requires prominent, large-scale, not-for-profit, intelligently curated spaces for its display. Private collectors spend large sums of money to acquire a single artwork but do not seem to comprehend the long-term value of incubating investigative artistic practice and scholarship that do not immediately yield shiny trophies for private possession. Grants through applications adjudged by juries coupled with ongoing mentorship through a research process can encourage young artists, curators and researchers to begin such investigations. Existing museums can also create spaces for contemporary projects and programmes to foster non-commercial art. This will have the additional advantage of placing experimental work in a critical dialogue with the existing museum collections.

Pakistan is a vast and diverse country. Its social and cultural dimensions, in which rapid transformations are transpiring not always peacefully, remain highly under-examined. Apart from the undoubtedly urgent and highly visible issues of violence and political and media scandals, a whole host of other processes are unfolding rather silently. These include dramatic changes in rural and urban ecologies; the rise of new informal economies and labour practices; the capture of natural resources and economic development by crony capitalism; the disastrous state of education and other human development indicators; growing sectarianism and a simultaneous scripturalisation and mediatisation of religion; the tensions and collaborations between linguistic groups and the formation of new ethnicities; the complex traffic between folk authenticity and televised popular cultures; the transformative spread of social media technologies; the reconstitution of social hierarchies in emerging digital and biometric infrastructures; and marked changes in familial structures and sexual mores — just to notate a few. Only a few artists are addressing such issues and that too only tangentially.

Committed contemporary art practice, its thoughtful curating and incisive criticism and scholarship on it can provide unrivalled insights into these consequential developments. These diverse analytical and creative perspectives will view Pakistan not through the lens of narrow exceptionalism but by developing comparative insights with reference to the adjoining regions of South and West Asia as well as to the larger Global South. But for that to happen, many aspects of contemporary art need to be reoriented towards research and process. The existing strengths of Pakistani contemporary art – its commitment to rigorous studio practice and object-making – need to be brought into a sustained critical conversation with other academic and creative disciplines.

An earlier version of this article was originally published in the Herald's August special issue celebrating 70 years of Pakistan. To read more subscribe to the Herald in print.

The writer is is an Associate Professor in Cornell University’s Department of History of Art.