It is raining on March 8, 2017 at the Torkham border post on the Pakistan-Afghanistan border. Half a dozen women and some children are sitting in an office compound out in the open. A security official approaches them and orders them to vacate the place that houses the offices of the paramilitary Frontier Corps, the tribal militia Khyber Khasadar Force and the civilian administration of Khyber Agency, the tribal area where the post is situated. He wants them to move to the Afghan side of the border. They all request him to let them remain on the Pakistani side.

One of them, Deeba, 29, is adamant. Clad in a shuttlecock burqa and crying incessantly, she insists: “I won’t go back to Afghanistan, come what may!” A resident of Khwar Nabi, a village in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa’s Swabi district, Deeba is carrying her Pakistani Computerised National Identity Card (CNIC) with her.

A few weeks earlier, she went to Jalalabad, the capital of Afghanistan’s Nangarhar province about 70 kilometres to the west of Torkham, to attend a family event at the house of her sister who is married to an Afghan. Before Deeba could return home, a blast at the shrine of Lal Shahbaz Qalandar in Sehwan on February 16 killed over 70 people, and Pakistan stopped all cross-border movement at Torkham, blaming the blast on terrorists who had come from Afghanistan.

By March 7, people and vehicles waiting to cross over stretched for kilometres on both sides of the border. Pakistan temporarily lifted the ban for a couple of days to let them pass. When Deeba came to know about the border opening, she rushed to Torkham along with her three children, including a two-month-old baby, but was stopped at the border post and told that she could not enter her own country because she had not left for Afghanistan with a visa. She protested that nobody had asked her for a visa when she went to the other side. Border guards had only looked at her CNIC and allowed her to exit Pakistan.

Stranded at Torkham, Deeba and her children, along with many others like them, spend a freezing night between March 7 and March 8 without proper shelter. The next day, they are neither willing nor equipped to pass another cold night in the open. “You have the power to kill me by opening fire with the gun you are holding,” she challenges the security official telling her to leave the compound. “But I won’t go back to Afghanistan.”

Deeba moves out only after the guard assures her that she will be allowed to go to her home in Swabi.

The assurance turns out to be a trap. As soon as she steps out, she is pushed back into Afghan territory. Realising that she has been deceived, she holds onto a steel railing as a female security official tries to push her into Afghanistan. “Za khpal watan ta zam (I have to go back to my country),” Deeba says in Pashto as she cries continuously.

“Why don’t you understand, sister?” asks a male security guard belonging to the local Afridi Pakhtun tribe. He is visibly softened by her crying.

“I do understand but you do not understand Pakhtunwali (the Pakhtun social code),” she responds.

The Afridi guard is annoyed over having to treat women unkindly, something that Pakhtunwali forbids, but he has no other option. “I am not at peace when I go to bed at night due to the way women are treated at the border,” he says. “But defying orders means termination from [my] job and I cannot afford that. I am the sole bread winner of my family.”

Gul Hasan, a Frontier Corps official responsible for managing the media, is taking photos in the meanwhile. He trains his camera on Deeba, clicks and sends her photo to his bosses as she is being pushed through the border rail.

An hour later, Colonel Umer Farooq, a Frontier Corps commander, circulates the photos to journalists in Landi Kotal, the headquarters of Khyber Agency about 10 kilometres to the east of Torkham, on the road that connects the border with Peshawar. He portrays Deeba as someone “going back to Afghanistan” and claims that the female security guard is helping her “as she could not handle all three children by herself”. Later the same day, Deeba and 470 other Pakistanis are allowed to enter their own country.

Khurshid Shinwari’s mother came from Ghazgay area near the Gardi Ghaus shrine in Afghanistan’s Nangarhar province. After her marriage many decades ago, she shifted to her husband’s house in Landi Kotal. When she fell terminally ill in 2001, her brothers came to see her from Nangarhar. They wanted to maintain links with her children after her death. “My eight-year-old daughter was thus engaged to the son of one of my uncles,” her son Shinwari says, a thickset man in his fifties.

He married his daughter off when she turned 20, after which she went to live with her in-laws in Afghanistan. She would cross the border frequently – and without any trouble – to meet her parents in Landi Kotal. In September 2016, she gave birth to a baby boy.

Around the same time, the National Database and Registration Authority (NADRA) declared her Pakistani identity card invalid because she had shifted to Afghanistan. Towards the end of January of this year, her son fell seriously ill and needed medical treatment not available in Afghanistan. She tried to bring him to Pakistan but was not allowed to enter the country of her birth because of her invalidated CNIC. “On February 4, her four-month-old son died,” Shinwari says, his green eyes looking wistful.

Pakistan is a favoured destination for a large number of Afghans seeking medical treatment, though as the case of Shinwari’s grandson shows, it is becoming increasingly difficult for them to get to the Pakistani side. Until late last year, Pakistani border authorities did not bother assessing their medical condition before letting them in. Only in November 2016, the civilian administration of the tribal areas appointed two doctors at Torkham to screen ailing Afghans trying to enter Pakistan. Even then, the bar to entry remained low and the number of Afghans crossing the border to visit Pakistani doctors and hospitals ran in the hundreds each day.

Since last December, screening has become more stringent and is undertaken by an army doctor. “[Just] 10 to 20 Afghan patients are allowed to enter Pakistan for medical treatment each day,” says an official of the civilian administration of Khyber Agency. Only those suffering from heart disease and cancer and those with bullet injuries are allowed instant entry, he adds. The rest are either sent back or told to bring in more documentary evidence to prove that they need urgent medical attention.

The border closure in February-March of this year also resulted in a large number of Afghan patients getting stuck on the Pakistani side. Even those who had valid travel documents were not allowed to cross the border at the time.

Hundreds of them are stranded in an under-construction mosque in Landi Kotal bazaar on a cold, early March day this year. They have been spending freezing nights in half-built shelters with next to no provisions. Misery and suffering abound.

Consider the story of Sardar Kareem. A slim man in his mid-forties with a black beard and wrinkled face, he has just one brown shawl to protect himself from night temperatures touching zero degrees. He belongs to Mohmand Darra area in Jalalabad and had his right leg amputated at Peshawar’s Hayatabad Medical Complex on February 17 because of complications caused by diabetes. “I have been staying in the mosque for the last five days because I have no money to stay in a hotel in Peshawar,” he says.

An ailing Afghan woman is sitting on a rough patch of land in Landi Kotal along the road that leads to Torkham. She underwent backbone surgery in January at a private hospital in Peshawar’s Dabgari Garden area and came back for a follow-up in February. As soon as her check-up was completed, she embarked on her return journey because she had left behind her nine-month-old child. Before she reached Torkham, cross-border movement was halted. Alone and almost penniless, she had no choice but to seek shelter in the mosque.

Many among the stranded are not ill but their stories are equally painful.

One of them, Raheemullah, wants to go home to Afghanistan because increased surveillance and checking have made it difficult for him to work anywhere in Pakistan. “I have been stranded here for the last five days,” says the 51-year-old labourer from Afghanistan’s Ghazni province. He has a visa to stay, but not work, in Pakistan and was employed building mud walls in Nankana Sahib district in Punjab when the local authorities arrested him in the wake of the Sehwan blast and put him in jail for a couple of weeks. He counts himself lucky that he was released.

Immediately after getting out of jail, he rushed to Torkham to go back to Afghanistan. By the time he reached the border, it had already closed. “The Pakistani government does not let us live on its own soil but at the same time it is not letting us go back to our home country,” he says.

Alam Gul Stankzai, a resident of Afghanistan’s Maidan Wardak province, starts crying out for help as soon as he sees someone approaching him. He used to sell dry fruit from a hand-driven cart in Rawalpindi where law enforcers would often stop him to check his identity papers. He moved to Peshawar hoping the situation would be better there. It was not. He sold his wares at throw-away prices and decided to leave Pakistan. “I will never come back [to Pakistan]. For God’s sake let me go back to my own land,” he implores.

Shafeeqa’s case is rather unique. She is a Pakistani but is marooned in Landi Kotal because she is desperate to be in Afghanistan. Her 19-year-old daughter died in Kabul earlier in the day and she wants to attend her funeral. With her three little daughters – still clad in their school uniforms – she is crying loudly and needs to be in Kabul at any cost. “My husband and relatives are waiting for me to be at the funeral but [the border guards] are not letting me cross into Afghanistan,” she says.

Shafeeqa came to Pakistan along with her family in the early 1980s after the Soviet Union invaded her native Afghanistan. Asif Shah, a Pakistani resident of Peshawar, fell in love with her and the two married. This was over two decades ago. Her husband now works in Kabul at an air-ticketing agency and their daughter was also married there before she was divorced a few months ago. She was living with her father in Kabul when she died.

Shafeeqa’s request for permission to cross the border has been turned down on the ground that she does not have an Afghan visa. She still hopes to see her deceased daughter one last time before she is buried. The burial, however, has already taken place without her knowledge. “My wife threatened to commit suicide if I buried our daughter in her absence,” says her husband by phone from Kabul the next day. But he could not put off the burial indefinitely.

Residents of Landi Kotal feel obliged to help the stranded under Pakhtunwali. A local tribesman says his family alone can accommodate as many as 20 Afghans in their hujra (an informal community centre), providing them shelter and three meals a day. However, he says, officials have warned the locals verbally against providing assistance to Afghans lest some militants benefit from their help. “We cannot afford to antagonise the authorities,” he explains.

AFrontier Corps official working at the Torkham border post explains why it is difficult for the authorities to tackle hardship cases on an individual basis. Between 6,000 and 7,000 people come to Pakistan from Afghanistan through the post every day, he says, not wanting to disclose his name for security reasons. Almost the same number of Pakistanis go to Afghanistan from the same spot daily, he adds.

Out of these, at least 400 people go to the other side of the border every morning and come back in the evening of the same day. They are mostly traders and manual labourers. About 20,000-25,000 Pakistanis live in Afghanistan as expatriate workers. Close to 1.3 million Afghans live in different parts of Pakistan as refugees, according to the United Nations high commissioner for refugees. Hundreds of trucks carrying goods to Afghanistan also pass through Torkham each day. The scale of movement at the post is too great to allow the border authorities the time to help individuals in distress, the official says.

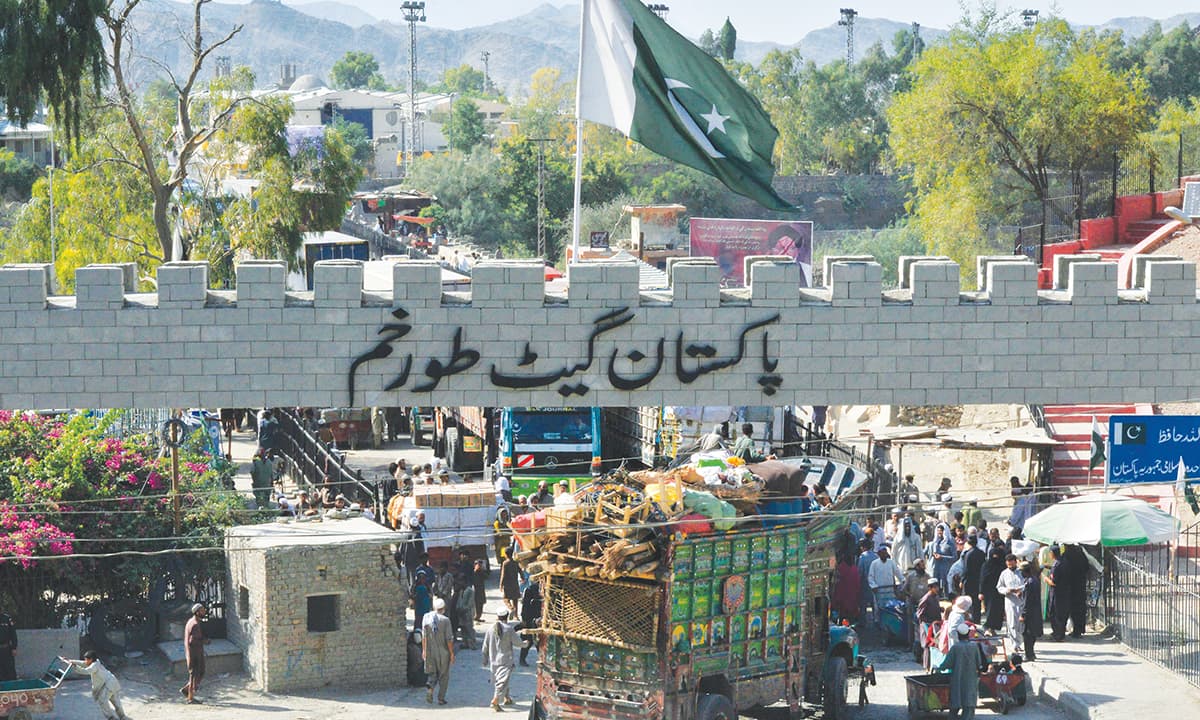

Before January 2016, the number of Afghans coming into Pakistan was as high as 20,000 per day and the checking of their documents was lax, if not entirely missing, says Shamsul Islam, a passport officer at Torkham border. He explains that Pakistan uses three different mechanisms to regulate border traffic at the post: immigration on valid travel documents examined through an integrated biometric system, movement of Pakistani Shinwari tribespeople to Afghanistan through a NADRA-operated system and, finally, movement of Afghan nationals on transit permits, known as rahdari passes, first issued by Pakistan on September 23, 2015.

Rahdari passes require renewal after every six months and were originally available to any Afghan sponsored by a Pakistani living in Landi Kotal tehsil of Khyber Agency. Four months later, their provision was restricted to Shinwari tribesmen living in Haska Maina, Speen Ghar, Acheen, Nazyaan, Dur Baba and Ghani Khel villages of Afghanistan. The total number of passes reached 16,000 when they were first issued, but went down to 3,800 by February 2017. Those who come to Pakistan using rahdari passes cannot travel beyond Shaheed Morr area, a crossway two kilometres east of the border post.

It was only after a terrorist attack at Bacha Khan University, Charsadda, in early 2016 that the Pakistani authorities started vigorously implementing these mechanisms to stop the infiltration of terrorists from Afghanistan. To that end, a four-layer security and clearance system was set up at Torkham. It is manned by the Khyber Khasadar Force, the Frontier Corps, Customs officials and the immigration cell of the Federal Investigation Agency (FIA) operating in that order. “Everybody crossing the border is required to pass through a proper system now,” says Islam.

Other measures include building an elaborate physical infrastructure.

A heavily-guarded concrete and steel portal, with multiple entrances, stands tall at the Torkham border post. A high steel-wire fence starts from the portal and stretches on both sides of a road in the Pakistani territory all the way to Shaheed Morr. Within the fenced-in area, different lanes are reserved for human and vehicular traffic going to Afghanistan. Vehicles and people intending to enter Pakistan from Afghanistan have separate lanes reserved for them. No cars or buses are allowed to cross through the post. Those wanting to cross to the other side are made to leave their vehicles near Shaheed Morr. They have to cover the rest of the distance on foot. The sick and the elderly are usually pushed in wooden wheelbarrows.

All these systems have been put in place over the last 12 months or so, according to Islam. They started when the National Logistics Cell (NLC) was assigned the task of streamlining the “haphazard” cross-border activities, he says. The cell built proper trade terminals and fenced the post, creating pedestrian and truck lanes and separate counters for departure and arrival.

Departments such as the FIA that check passports and visas, and Customs that levies taxes on imports and exports, meanwhile, have increased their strength at the post, says the Frontier Corps official. Security pickets have been reinforced, patrolling has been increased and the presence of security and intelligence agencies has been strengthened around Torkham, the passport officer says.

He believes that the Afghans stranded in Landi Kotal must have incomplete travel and identity documents. The security agencies, he says, have detained 400 or so other Afghans who were trying to cross the border without legal documents, he says. They are to be thoroughly investigated: Those who are found not to be involved in any militant or terrorist activity in Pakistan will be declared ‘white’ and will then be handed over to the civilian administration which will release them after charging 5,000 rupees in fines for attempting to cross the border illegally. The ‘grey’ detainees will be subject to further probes and the ‘black’ ones will be presented before the courts.

Pakistani security forces have also blocked three rather unfrequented routes near the Torkham border known to have been used by terrorists and militants to enter Pakistan, says the official. Shoot-at-sight orders have been issued if and when anyone is found trying to use those routes, he adds. “The infiltration is nil now.”

Construction of permanent structures on the border – marked by the British-era Durand Line that Afghanistan has historically refused to accept – has been seen in Kabul as a disagreeable act. The Afghan government’s attempt to stop Pakistan from going ahead with the construction of various facilities at Torkham led to a clash last year between the border forces of the two countries. On June 12, 2016, Major Jawad Changezi, an army officer working with the Frontier Corps at the post, lost his life to firing from the Afghan side.

His death made Pakistan slow down commercial traffic that takes all kinds of goods, including food and home appliances, from Pakistan – both by legal and illegal means – to Afghanistan. Border guards were told to strictly enforce the provisions of the Afghanistan-Pakistan Transit Trade Agreement (APTTA) of 2010 that aims at, among other things, curbing illegal re-entry of Afghanistan-bound goods into Pakistan. Imported from China, Japan, East Asia, Europe, North America and the Gulf, theoretically for use in Afghanistan, these goods often end up in bazaars and markets in border towns such as Peshawar and Chaman.

Under one of the most important clauses in the agreement, every truck carrying imported goods to Afghanistan is required to make a security deposit of 600,000 rupees to Pakistani authorities at Karachi Port. The money is returned only if the truck has crossed over to Afghanistan and unloaded all its goods in that country. If it does not exit Pakistan or comes back to Pakistan without unloading its contents, the security deposit is forfeited.

Though the agreement was signed about seven years ago and rules and regulations for its implementation were formed in 2011, it is only recently that Pakistan has deployed the required tools and human resources at Torkham and Chaman to enforce it strictly. As a consequence, say civilian officials in Khyber Agency, trade traffic has witnessed a sharp decline at Torkham. In previous years, more than 800 trucks per day crossed the border to go to Afghanistan, says one official. This number has deceased by half, he adds.

Irfan Muhammad, a clearing agent who coordinates between Afghan traders and truckers and Pakistani taxation authorities at Torkham, also believes that Pak-Afghan goods traffic has gone down by at least half in recent months. His firm would help at least 100 trucks to clear the customs procedures each day before the border controls became strict. This number has gone down to 40-50 a day, he says.

More than anything else, the decline is having a serious impact on Pakistan’s exports to Afghanistan. About 500-600 trucks carrying cement used to cross into Afghanistan on a daily basis in the not-so-distant past. “Now their number has declined to 150-200 a day,” says Muhammad.

Afghan officials love to point out that Pakistan is hurting its own commercial interests with tighter border controls. “We have a number of other trade options like Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Azerbaijan, Tajikistan and Iran and we are using them after restrictions have been placed on trade through Chaman and Torkham,” says Dr Abdullah Waheed Poyan, the Afghan consul general in Peshawar. He confirms that annual trade between the two countries has gone down to about 1.5 billion US dollars from its peak of 2.5 billion US dollars a few years ago.

The other direct impact of the changes in border trade has been on truck drivers. Earlier, drivers and their helpers from the two countries could cross the border without passports or visas, says Poyan. Now, Pakistan requires Afghan truckers to acquire multiple-entry Pakistani visas. They have to spend additional time and money to obtain them, he says.

The drivers who do not require a visa even now are also unhappy. Muhammad Saleem, a 38-year-old former teacher, was once so enticed by the prospect of making a decent living from cross-border traffic that he quit his job at a school for Afghan refugee children in Haripur district of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in 2008 and became a taxi driver.

He would earn 18,000-20,000 rupees a month driving a cab between Haripur and Torkham four to five days a week. This was a great improvement over his 7,000 rupees a month salary as a teacher. But commercial traffic between Pakistan and Afghanistan has gone down so much in recent months that he can get work only once a week. “It has become extremely difficult to make ends meet,” he says.

Decline in demand for trucks and containers has led to a reduction in their fares. A truck that could be hired for 350,000 rupees for a single consignment early last year is available for 260,000 rupees now. The truckers also have to wait longer than in the past at Karachi Port due to the increase in time that Afghan transit trade now takes to clear. While this raises costs for importers who have to pay the shipping companies an additional 80-90 US dollars per day for each container, the wait for each truck to get its consignment often stretches to about six days, says Muslim Khan, a 33-year-old truck driver.

A Shinwari tribesman from Afghanistan, he has been driving a goods container for the last four days. On January 3 of this year, he arrives at Takhta Baig, a place just outside Peshawar in Jamrud tehsil of Khyber Agency, after starting his journey at Karachi Port four days earlier. He will need to drive for another six hours or so to reach Jalalabad.

His long hair falling from beneath his red cap, Muslim Khan sets off from Takhta Baig for Torkham early in the morning. His younger brother, Shamullah, is sitting next to him in the driver’s cabin. Their 22-wheel vehicle is moving at a very slow pace because of the massive amount of goods it is carrying. They stop as they approach a checkpoint.

Shamullah gets down and hands some money to an official. The vehicle moves to the next checkpoint where the same act is repeated. Shamullah performs the same routine until their vehicle has crossed all the 14 checkpoints between Takhta Baig and Torkham. “It is impossible to pass a checkpoint without paying kalang (extortion),” says Muslim Khan. Both Pakistani and Afghan truckers pay kalang worth many thousand rupees before reaching Torkham, he claims.

Shakeel Ahmed, a customs clearing agent at Torkham, makes a similar claim. Various Pakistani departments, he says, have set up a number of checkpoints on the 45-kilometre stretch of road between Peshawar and Torkham (many of these have been set up only in recent months) where each trucker pays about 7,000 rupees.

This money never goes to the national exchequer. Instead, it lands in the pockets of those manning the posts, he alleges.

A stretch of shopping centres on the northwestern outskirts of Peshawar marks one side of a road that links the city with Jamrud and then onwards to Torkham. Multistorey shopping complexes and small stores located here are brimming with all types of goods — automobile spare parts, lubricants, tyres, electronics, crockery, blankets, toys, cosmetics, clothes, shoes, canned foods, chocolates, drinks, even dry fruits. This is the famed Karkhano Market, perhaps the biggest and the most known place to buy smuggled goods in Pakistan.

Buyers from many parts of northern and central Pakistan find it a convenient and cheap source of luxury goods that may cost an arm and a leg if purchased from superstores and markets dealing in legal imports.

Gul Sher (not his real name), a Shinwari tribesman from Landi Kotal, has been involved in smuggling goods to Karkhano Market for years. He describes how he would carry smuggled goods through Torkham on hand-pushed carts. Once on the Pakistani side, those goods were transferred to trucks that carried them to Peshawar. A truck full of smuggled items would cost 450,000 rupees, says Sher. The cost included the bribes required to buy officials manning the checkpoints (approximately 300,000 per truck) and the fare (approximately 50,000 rupees). Each month, Sher and his associates would bring to Karkhano Market four to five trucks containing smuggled goods. Hundreds others from the Shinwari tribe did the same.

Most of that traffic is gone now. Business has been bad for shopkeepers at Karkhano Market for quite some time. Many shopping centres wear a deserted look. Smuggled goods cost almost as much as legally imported ones now.

Fazle Wahid, a middle-aged trader at Karkhano Market, has been dealing in smuggled blankets for the last 16 years. He complains his business has come to a halt due to “extraordinary restrictions” on the border. “For the first time after I started this business, I am suffering a loss of 30,000 rupees to 35,000 rupees a month,” he says. A double ply blanket available at Karkhano Market was cheaper by 1,500-2,000 rupees than the ones legally imported, but that difference has diminished to the extent that customers belonging to Punjab do not see any benefit in shopping at Karkhano Market anymore, he says.

Businessmen in Landi Kotal, another major hub of smuggled goods from Afghanistan, face a similar situation. Shah Noor, a local trader in his mid-forties who deals in tyres smuggled from Afghanistan, is worried about the future of his business. A pair of smuggled tyres used to be available at 34,000 rupees in Landi Kotal before restrictions at the border, while the legally imported ones cost 43,000 rupees. The price difference has all but vanished, he says.

If Wahid Khan Shinwari, secretary general of the Landi Kotal Customs Clearing Agents Association, is to be believed, half of Landi Kotal’s roughly 25,000 people have been affected by the strict border management. Others point out that 1,300 taxi cabs and 800 buses plying between Torkham and Peshawar have almost stopped their operations because of the declining number of people crossing the border. Many of the 700 or so customs clearing agents working at Torkham are also left with next to no work. Hundreds of people working as carriers of smuggled goods and earning 500-1,000 rupees a day have become jobless.

Wahid Khan Shinwari recalls a meeting between local tribal elders and the Frontier Corps commandant on March 1 of this year. The objective of the meeting was to discuss the impact of changes in border management on local trade and employment. “We warned the commandant that unemployed youth may join terrorists who offer 20,000 to 25,000 rupees a month to those willing to work with them,” he warns.

Not that smuggling has entirely vanished.

The only traditional smuggling route where cross-border movement of goods has come to a complete halt over the last two years lies to the north of Torkham in Shalman area. Security there has been highly tightened to stop the infiltration of militants belonging to Daesh and Jamaat-ul-Ahrar from the Afghan side, so much so that even cross-border movement of local tribespersons has been banned.

Shalman is inhabited by the Haleemzai and Tarakzai sub-clans of the Mohmand tribe. They have blood relations with people living on the Afghan side of the border. Many of them would go to Afghan villages without any hindrance until a few years ago. “For the last seven years, we have had no links with our relatives and friends in Afghanistan,” says Gul Haq Khan, a resident of Sheen Pokh village in Shalman. Afghan security forces let them cross the border even now but, he says, “When we return, Pakistani security forces subject us to a thorough probe in their lock-ups.”

Pakistani pickets dot the area at two-kilometre intervals to keep a strict watch on the border. Commuters to Shalman from other parts of Pakistan are stopped at the Ghakhay checkpoint manned by the Swat Scouts.

A signboard to the side of the picket warns: the camera lens is watching you. The locals advise outsiders against introducing themselves as journalists. “[Security officials] will never let us cross the picket if they come to know that you are journalists,” one of them says. Only a few metres ahead, there is another checkpoint, manned by the Khyber Khasadar Force. Pakistani mobile phone signals do not reach here. If your phone is on international roaming, you may catch signals from towers installed in Afghan territory on the other side of a river that marks the boundary between the two countries.

Khasadars warn all visitors to discontinue their travel to Shalman and go back. “We do not want to put your lives at risk as both Daesh and Jamaat-ul-Ahrar militants are present on the other side,” says a 50-something Khasadar official. On May 21 of this year, the Khyber Agency’s civilian administration “ordered thousands” of residents of Sheen Pokh “to vacate their houses” after a mortar shell fired from Afghanistan killed a woman and critically injured a boy, according to a report in the daily Dawn.

Smugglers, instead, are using a new route — through Zakhakhel Bazaar located to the southwest of Landi Kotal amid high mountains and narrow passes. Due to the presence and movement of militants through the area, outsiders are not allowed to enter it without permission from security agencies.

To overcome this hurdle, smugglers find local partners from the Zakhakhel clan of the Afridi tribe who help them smuggle goods from Afghanistan’s border areas to Zakhakhel Bazaar on mules and camels. From there onwards, the goods are shifted to Landi Kotal and Karkhano Market on trucks.

Smugglers also need to pay protection money (500,000 rupees for each truck) to Tauheedul Islam, a pro-government militant organisation that has been fighting against the fighters of another militant organisation, Lashkar-e-Islam, since 2011.Before that year, the two groups were united and waging a war against Pakistan in collaboration with the Pakistani Taliban.

Tauheedul Islam has a presence all along the smuggling route. Its commanders have a monopoly over trucking operations and they have disallowed the entry of any vehicles into the area other than those they themselves own. It helps them charge high fares (300,000 rupees per truck). It also keeps the volume of smuggled goods low because of the limited number of trucks the commanders can deploy. If smugglers want to expedite goods transportation, they have to pay an additional 200,000 rupees to Tauheedul Islam for each consignment.

The result is an increase in the price of smuggled goods and a decline in their volume, thus leading to a decrease in the money that a smuggler can make. By the time a truck reaches Karkhano Market from Zakhakhel Bazaar, its total transportation cost amounts to 800,000 rupees — more than twice as much as the cost of transporting a truck from Torkham to Karkhano Market. This erodes the profit margins shopkeepers in the market once enjoyed.

The road that leads to Zakhakhel Bazaar branches off from the Peshawar-Torkham highway a little to the east of Landi Kotal. It veers southwest for many kilometres to reach a mountaintop overlooking the bazaar. On a February day this year, officials of the Frontier Corps and the Khyber Khasadar Force are bunkered inside a small checkpoint on the hilltop to avoid the harsh winter wind. They stop every vehicle passing by, check the identity of its occupants and disallow all non-locals, including mediapersons, from travelling downhill. Only the commandant of the Frontier Corps and the political agent of Khyber Agency have the authority to grant them entry.

Smuggling through this area is unthinkable without the knowledge, if not connivance, of security personnel and civilian officials. A member of the civilian administration of Khyber Agency acknowledges that much, but he hastens to add that his department is not aware of any formal or informal, verbal or written, agreement between the state and Tauheedul Islam to allow smuggling. “The agreement, if there is any, has been reached between the non-civilian officials (that is, security forces) and the long-haired people (that is, militants),” he says.

Local sources say Tauheedul Islam makes about 150 million rupees a month through its patronage of smuggling. They say the money helps the organisation pay for its anti-terrorism operations. It maintains a force of around 1,100 fighters to keep peace in the area and has lost 196 of its associates in clashes with the militants of Lashkar-e-Islam, they point out. It is to compensate for this that Tauheedul Islam has been given this incentive, says a local journalist who attended meetings with security officials where information about the arrangement was shared.

Fayyaz Khan, a resident of Shabqadar tehsil of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa’s Charsadda district, is waiting to cross the border at Kharlachi, a border post in Kurram Agency. He is going to Afghanistan to participate in a football game. The Frontier Corps personnel posted at the crossing look at his CNIC and give him the go-ahead to move to the other side of the border. “Hopefully I will manage to come back,” he says.

Kharlachi does not have anything like the elaborate security arrangements that Torkham has. There are no immigration officials to check passports and visas. A handful of Afghans can be seen crossing the border without visas and passports. Most of them claim to be coming to Pakistan to seek medical treatment. A few Customs officials examine trucks passing through the post and levy export taxes on their contents.

For some unknown reason, Kharlachi is a no-go area for journalists. Earlier this year, local facilitators advised a team of journalists visiting from Peshawar against disclosing their professional identity to the officials at the border post. When one journalist took photographs with his camera, a Frontier Corps official grabbed the camera and deleted all the photos of the crossing.

Security is strict on the road to Kharlachi. The first major picket is located at a place called Hindu Dhand, just before a road coming from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa’s Hangu district enters Parachinar city, the headquarters of Kurram Agency. All vehicles – cars, vans, buses, trucks – wait at the picket in a long queue before a young soldier with green eyes, a brown beard and a fair complexion examines their papers. Outsiders are required to show their original CNICs and get a pass to enter Parachinar.

Those who want to go to Kharlachi have to pass through another checkpoint at a place called Ghulam Jan. Before a third picket arrives at Malli Kalay village, about eight kilometres north of Parachinar, the road turns southwest through a valley surrounded by snow-clad mountains of the Koh-e-Sufaid range. Population is sparse here. Houses are scattered at the foot of the hills.

A couple of other security pickets appear on the 19- kilometre road before it reaches Kharlachi. The officials at these pickets ask routine questions: if all vehicles have valid registration documents and whether all commuters carry their CNICs.

Until last year, Kharlachi was a bustling trade post. Every day 400 or so trucks loaded with such goods as fresh fruit, rice, wheat, cooking oil, clothes and footwear would go to Afghanistan from here, says Haji Rauf Hussain Turi, a tribal elder in Parachinar. About 150 trucks a day exported Kinnow alone during the winter of 2016, he says. Now, this entire traffic has been reduced to 150-200 trucks per day, he adds.

A mud track passes through the modest border gate at Kharlachi. A bevy of shiny new cars is parked on the Afghan side — waiting to be smuggled into Pakistan.

“Eight to 10 vehicles on average are smuggled every day through certain border crossings in Kurram Agency,” says Habib Hussain, who has been running an automobile business in Parachinar for over 20 years. He puts the total number of smuggled vehicles in the agency at 10,000. These are known as ‘non-custom paid vehicles’ since they are brought into Pakistan without paying any import taxes.

The Frontier Corps personnel seized 50 non-custom paid vehicles early in January of this year. Enraged over the seizure, local tribal elders met the general officer commanding of the corps, asking him to order their release. They submitted to him that he should rather take to task those border security officials who let the vehicles into Pakistan in the first place, says a source privy to the meeting.

Local traders dealing in smuggled vehicles say the only change their business has seen in the wake of tightened border controls is a rise in the rate of the bribes they pay to the officials at various checkpoints. “A year ago, we would cross the border, buy a vehicle and hand it over to a carrier to give it back to us in Parachinar,” says Habib Hussain. The carrier would charge only 5,000 rupees. Now his rate has increased manifold.

Talib Hussain, who has been working as a carrier for years, says he has started charging 25,000 rupees to bring a smuggled vehicle to Parachinar. Of this, he claims, 20,000 rupees go to the officials of various departments.

The other much-smuggled item is urea-based fertilizer. Since Kurram Agency in general and Parachinar in particular have suffered a number of bomb blasts and suicide attacks over the last few years, the government banned the sale of urea fertilizer there because of its usage in bomb manufacturing. The ban came into effect on November 20, 2015 but has not eliminated the sale of urea in the agency. “[The fertilizer] is being smuggled from Iran, Russia and Tajikistan,” says Haji Rauf Turi Hussain, the tribal elder.

Kurram Agency is a fertile region with 144,280 acres of cultivable land. Its farmers grow wheat, rice, potatoes, tomatoes and many other vegetables. “Our tomatoes go to Rawalpindi, peanuts and turnip to Lahore and potatoes to Karachi,” says Shabir Hussain, who owns a 20-acre farm in Parachinar. More than 80 per cent of households in the agency are dependent on agriculture, he adds.

Local farmers have only two choices in the wake of the ban on urea and both are financially unfeasible: they can avoid using fertilizer, which will reduce their yield and consequently hit their income, or they can use smuggled fertilizer available at a high price which will increase their input cost and decrease their profit margin.

A bag of urea is available at 1,450 rupees in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa’s Hangu district that abuts Kurram Agency in the east, says Shabir Hussain. In Parachinar, it is available at 3,000-3,300 rupees per bag. “This has inflicted a colossal loss on our economy.”

Tribal elders apprised the military authorities about the problem last year. “They assured us that it would be resolved soon,” says Khurshid Anwar, another farmer in Parachinar who owns 50 acres of agricultural land. So far, nothing has come out of that promise, he says.

The Ghulam Khan border crossing is quiet and calm even though it is located in North Waziristan Agency where a military operation against the Taliban has been going on since 2014. A two-lane road that connects it with Miran Shah, the headquarters of the agency, is deserted on a sunny day early this year. Built with financial support from the United States, it was inaugurated by then Chief of the Army Staff General Raheel Sharif in November 2016.

It passes through a newly-built gate at the border, enters the Afghan area and continues moving westwards before disappearing into the horizon. A short, 120-metre patch of land on both sides of the border has been left unpaved since its ownership is disputed between Pakistan and Afghanistan, a small but significant sign that all is not well between the two countries.

Pakistani security forces keep a close watch on the border crossing but no Afghan soldiers or officials are visible on the other side. They have set up their post on top of a hill that overlooks the crossing, says a Frontier Corps official. The first Afghan checkpoint on the ground is located about a kilometre from the line marking the boundary.

Kamran Afridi, who works as a political agent, the highest civilian official in North Waziristan agency, expected the border to open for commercial traffic and human movement soon after the road was inaugurated. He says his staff had made all the required arrangements. “We had meetings with Afghan customs officials and the representatives of the Afghan chamber of commerce. We also made arrangements to install machinery for scanning goods to be traded,” he says. But terrorist attacks in February put paid to his plans. “The escalation of tension on the border [after the terrorist attacks] became a stumbling block,” he explains.

Border tensions have also hampered the repatriation of North Waziristan’s residents from Afghanistan, says Afridi. About 9,070 families had moved to the other side of the border when the military operation, Zarb-e-Azb, started in the agency three years ago. Only 1,735 families returned to Pakistan by March 23, 2017, he says.

Bab-e-Dosti, a towering structure that marks the Pak-Afghan border near Chaman in Balochistan, has two wide gates for the movement of vehicles and two side doors for people to pass through. Queues of 22-wheeler trucks and containers, carrying different types of goods, stretch as far back as two kilometres into Pakistani territory from the border. Hundreds of people, both Pakistanis and Afghans, can be seen crossing the border at any time of the day. To regulate this massive flow of people in an orderly and secure fashion, heavily-armed personnel of the Frontier Corps in their camouflage uniforms have been deployed everywhere around the border post.

Pakistanis living in a 15-kilometre radius from Bab-e-Dosti can cross into Afghanistan without passports and Afghan visas. Afghans living within the same distance from the border, too, do not need passports and Pakistani visas to enter Pakistan. Under this arrangement, thousands of Achakzai tribesmen from Pakistan go to Afghanistan every morning as traders and labourers to Wesh Mandi, a trade hub about three kilometres west of Bab-e-Dosti. They all come back in the evening. A similar number of Afghan labourers come to Pakistan to work in Chaman during the day and return in the evening. Pakistanis only need to show their CNIC to move across the border. Afghans are required to produce their tazkiras, or biodata forms, to do the same.

The problem usually occurs over the authenticity of Pakistani CNICs and the verification of Afghan tazkiras. Afghan border guards do not accept photocopies of Pakistani CNICs. They want to see the original. Pakistani border guards also need to see the original tazkiras but the problem with these tazkiras is that, unlike Pakistani CNICs, they are neither computerised nor issued by a central authority.

On April 1 of this year, a clash erupted between Pakistani security forces and the people crossing the border after the latter protested against delays in the scrutiny of documents. The subsequent firing by border guards left three civilians injured and led to a closure of the border for about three hours. Yet, those Afghans wanting to cross the border on foot were allowed to do so. Only those riding trucks or other vehicles were not permitted to move across. Afghan border guards, however, did not stop any Pakistanis carrying original CNICs from crossing over from Afghanistan into Pakistan. Even an officially closed border was not really closed after all.

Pakistan also allows a free flow of edibles to Afghanistan in small quantities. At a little distance from Bab-e-Dosti, Afghans can be seen taking bags of flour and other kitchen items in wheelbarrows after unloading them from trucks parked on the Pakistani side of the Durand Line.

Another type of goods – vehicles – also move across the border without let or hindrance.

Saddam Achakzai, a car dealer in Chaman, discloses that smuggling of vehicles from Afghanistan did not stop even when the border was closed due to terrorist attacks earlier this year. Strict border security has increased the money given in bribes at different checkpoints, he alleges, but it has not halted smuggling.

He shows off a 2008 model Toyota Corolla Axio car a carrier has brought for him in March of this year. He claims to have purchased it paying 400,000 rupees to its Afghan owner. The carrier charged him 35,000 rupees to drive the car through the border to his showroom in Chaman. He will sell it at 450,000 rupees. “My profit is 15,000 rupees.”

Izzat Khan, a 23-year-old science graduate, is a car carrier in Chaman. “I mostly smuggle Toyota Fielder cars,” he says. According to him, the money he charges for bringing a vehicle from Afghanistan includes 2,500 rupees paid to Afghan border officials and 20,000 rupees given to officials at Bab-e-Dosti. When the border is closed for some reason, money paid to Pakistani officials jumps to 60,000-70,000 rupees for each car, he claims.

A Levies Force official still believes that cross-border movement is heavily controlled at Bab-e-Dosti as compared to the past. “Chaman was like home to Afghans. [Spin Boldik, the Afghan town on the other side of the border,] was the same for Pakistanis,” he says, talking about the situation a few years ago. “Visitors from Karachi could cross the border in their vehicles. They would come back at their own convenience.”

"We are lying between paradise and hell,” says 20-year-old Saifullah, a slim man with a bearded, smiling face. He is a resident of Killi Mazal village, named after his father Haji Muhammad Afzal (also known as Haji Mazal) and located right on the border to the south of Bab-e-Dosti. The paradise to him is Pakistan.

Back in 2013, the Frontier Corps established a checkpoint, known as Iqbal Picket, at the lone road that passes outside his village. No village resident can pass through the picket without carrying their original CNIC. Outsiders are not allowed to enter the village even when they have their identification papers with them, unless they are accompanied by a local. The restrictions have only become more stringent after the border clash between Pakistan and Afghanistan at Torkham in June 2016.

Entrance to the village is blocked by a wire fence. Villagers cannot exit the fenced-in village before 7:00am. Those who are already outside the village cannot get back in before noon. By 7:00pm, entry and exit are both prohibited till the next day. This has resulted in some tragedies.

“In January last year one of my cousins was stabbed. He died of excessive bleeding because we could not take him to a hospital in time due to the closure of the picket,” says Abdullah, a young villager. There is an alternative route through a nearby village, Killi Jahangir, but to use that route the villagers have to enter Afghanistan and pass through an Afghan checkpoint. “This is an uphill task,” he says.

Afghanistan claims the two villages, as well as a third one, Killi Luqman, fall within its territory. Electricity supplied to these villages has a Pakistani source, the Quetta Electric Supply Company, and education and communications are provided by the Pakistani state and businesses. All this has not abated Afghan claims. In March this year, Afghan border police, while patrolling Killi Luqman, directed the villagers to remove Pakistani flags from their houses.

On May 5, the dispute over the villages erupted into a full-blown armed clash between the two countries. Pakistani authorities claim Afghan border guards fired at a census team working in Killi Luqman and Killi Jahangir; Afghanistan claims heavily armed Pakistani border guards intruded into Afghan territory to occupy it.

At least nine people, four of them Frontier Corps personnel, were killed in firing from the Afghan side.

My beloved is on other side of the border and I am [lingering] on this side

[I] swear I cannot cross it over

[Because of the] dividing line of Torkham

My beloved is on other side of the border and I am [lingering] on this side

I said which place is this

[My beloved] said this is Afghanistan

I said I would go there at any cost where my beloved lives

I said I would just cross over to it

[My beloved] said no you’re not fortunate enough

Shahnawaz Tarakzai, 40, sings these lines in Pashto as he reaches Bab-e-Dosti. A Mohmand tribesman and a journalist, he comes from Michni, a village located 29 kilometres northwest of Peshawar in Mohmand Agency. His area is replete with the dreaded militants of the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan’s Jamaat-ul-Ahrar faction.

Tarakzai’s impromptu song is a reiteration of the fact that many Pakhtuns living on both sides of the 2,590-kilometre long Durand Line, drawn in 1893 to mark the border between British India and Afghanistan, do not accept it as a legitimate international frontier.

Dr Abdullah Waheed Poyan, the Afghan consul general in Peshawar, echoes these sentiments when he says Pakhtuns living along the Durand Line have centuries-old ties with each other. He is critical of Pakistani measures to strengthen border controls and fence most parts of the Durand Line. “Restriction on the free movement of people … is creating problems for two brothers,” he says in an interview. “Thieves do not force their way into a house through the main gate, but they use other options,” he responds to the Pakistani argument that militants based in Afghanistan enter Pakistan through various routes across the Durand Line to commit terrorist activities. He insists restricting cross-border movement is not “a step towards the solution” of this problem.

The history of the Durand Line remains so controversial that it is almost impossible to reconcile the differences between those who see it as a legal boundary and those who see it as an illegal imposition by a colonial administration.

Those who see the Durand Line as a British construct argue that Pakhtun areas included in British India through its demarcation were actually leased by the Afghan king for 99 years — a lease that expired in 1992.

Their second contention is that the Durand Line was drawn on paper and was never physically demarcated on the ground. Their third argument is that many parts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and almost all of the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (Fata) were historically parts of Afghanistan and were annexed by the British under the Durand Line Agreement of 1893, which itself was skewed because it was not among two equal parties but between the Afghan king, Abdur Rahman Khan, who needed help to quell an insurgency and the British Empire that would not assist him without receiving something in the bargain.

Abdur Rahman Khan, who ruled Afghanistan between 1880 and 1910, was the first to make claims over certain territories now in Pakistan. In his autobiography, published in London in 1900, he stated: “… the Indian Government took all the provinces lying to the south-east and north-east of Afghanistan, which used to belong to the Afghan government in early times, under their influence and protection. They gave them the name of ‘independent,’ and … called them the neutral states between Afghanistan and India.”

A map of the ‘independent’ states, or Yaghistan as they are known in Pashto, which a viceroy of India provided to Abdur Rahman Khan, included the Waziri areas, New Chaman, Chagai, Buland Khel, the whole of Mohmand, Chitral and Asmar, the latter of which is now in Afghanistan. The Afghan amir subsequently renounced his claims over the railway station of New Chaman, Chagai, part of the Waziri areas, Buland Khel, Kurram, the Afridi areas, Bajaur, Swat, Buner, Dir, Chilas and Chitral.

The text of the Durand Line Agreement, signed on November 12, 1893, between the Afghan monarch and Henry Mortimer Durand, categorically declares these areas out of the king’s jurisdiction. “The Government of India will at no time exercise interference in the territories lying beyond this line on the side of Afghanistan, and His Highness the Amir will at no time exercise interference in the territories lying beyond this line on the side of India,” reads the agreement.

But decades after the accord was signed, Afghanistan continued making territorial claims over Pakhtun lands that had become part of British India. In the early 1940s, the Afghan government sent “a series of dispatches” to the British government in India that “expressed its desire to absorb the Pakhtun areas located along the southern part of the Durand Line”. The Indian government, however, categorically turned down this demand, says Lutfur Rehman, a PhD student at the National Defence University, Islamabad who is also a radio broadcaster.

When the British announced their plan to partition the Indian subcontinent on June 3, 1947, he says, Afghanistan again sent a dispatch to London and Delhi saying that the people living in the Pakhtun regions east of the Durand Line “should be given the option of becoming independent or of joining either Pakistan or Afghanistan.”

Afghanistan also opposed Pakistan’s entry into the United Nations as an independent state without addressing Afghan claims to Pakhtun areas. Addressing the United Nations General Assembly on September 30, 1947, Afghan envoy Hussain Aziz said: “… we cannot recognize the North West Frontier Province (now known as Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) as part of Pakistan so long as the people of the NWFP have not been given an opportunity free from any kind of influence – and I repeat – free from any kind of influence, to determine for themselves whether they wish to be independent or become a part of Pakistan.”

Afghanistan’s Loya Jirga, or Grand Assembly, passed a resolution on June 30, 1949, to unilaterally revoke all treaties, conventions and agreements signed between Afghanistan and British India. During the 1950s, Pakistan and Afghanistan engaged in several border clashes, prompting Pakistan to stop the transport of petroleum shipments to Afghanistan for three months. In 1953, the Afghan government unilaterally abrogated the Anglo-Afghan Treaty of November 1921, under which Kabul had acknowledged the Durand Line as an international frontier between Afghanistan and India. In 1973, Sardar Mohammad Daud Khan became Afghanistan’s president and officially started celebrating Pakhtunistan Day to mark unity among Pakhtuns living on both sides of the Durand Line.

Lutfur Rehman claims that many of the Pakhtun areas on the Pakistani side of the Durand Line were never under Afghanistan’s political control. Those that were a part of Afghanistan were so either for a brief period or through arrangements that gave them a large amount of internal autonomy. Peshawar remained under the full control of Afghanistan only between 1747 (when Ahmad Shah Abdali defeated its Mughal governor Nasir Khan) and 1822, when Sikh emperor Ranjit Singh snatched it from Afghan king Shah Shuja, he says.

In the region that constitutes today’s Fata, he adds, the Afghan government had a limited and weak influence, if any at all. Areas such as Chitral, Bajaur, Dir and Swat, according to him, were all autonomous states which neither the Mughals nor the Afghans could ever successfully bring under their control. Pakistan-based Pakhtun nationalists have never found such arguments easy to accept.

Aurangzeb Kasi, a Quetta-based Pakhtun leader who until recently was heading the Balochistan chapter of the Awami National Party (ANP), recalls accompanying Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, the legendary Pakhtun nationalist leader also known as Bacha Khan, when he made a month-long visit to Balochistan in 1986. Wherever Bacha Khan talked to people, he would say that he “wanted to materialise the dream of Ahmed Shah Abdali to unite Pakhtuns from the Jhelum river [in Pakistan] to Amu Darya [in Central Asia] under the umbrella of [an independent state of] Pakhtunistan.” Abdali, who came from a Pakhtun tribe, was the first Afghan ruler to unite the tribal society of Afghanistan into a state in 1747, says Kasi who visited Kabul to attend Pakhtunistan Day in 2015.

Now that Pakistan has started fencing its border with Afghanistan, Kasi sees it as an attempt to make the Durand Line a permanent frontier. “Afghans will not accept that,” he warns. Pakistan, he says, could not convince even its diehard supporters such as the Afghan Taliban’s founding amir Mullah Omar and former Afghan prime minister Gulbuddin Hekmatyar to accept the Durand Line as a permanent border between the two countries.

Dr Khadim Hussain, a Peshawar-based political analyst and a Pakhtun nationalist, argues that the Treaty of Rawalpindi, signed in 1919 between British India and Afghanistan, has superseded the accord which brought the Durand Line into being. According to that treaty, he claims, any future arrangement regarding Pakhtun areas on the east of the Durand Line was to be negotiated with Afghanistan. The treaty does not seem to have this provision, however.

But Khadim Hussain adds that Pakhtun nationalism has nothing to do with the validity or invalidity of the Durand Line and that the geographical unification of all Pakhtuns was never the objective of Pakhtun nationalist politics in Pakistan. He sees Pakhtunistan Day as a “pressure tactic and a ploy” vis-à-vis Pakistan. “Pakhtun nationalist parties have never accepted this tactic,” he says.

He also likes to point out that the Pakistani ruling elite has always seen Pakhtun nationalism from a territorial perspective, treating it as a threat to the territorial integrity of Pakistan. “It was due to these fears that the nascent Pakistani state toppled the elected government of Dr Khan Sahib [Bacha Khan’s brother] on August 22, 1947, and arrested Bacha Khan in 1948, despite the fact that he had taken an oath [of allegiance to Pakistan] as a member of the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan.”

A senior Pakistani government representative, who has experience working with the foreign office at a senior level, acknowledges “the fact that Afghanistan does not accept this border”. Pakistan, he suggests, “should have got it accepted during the Taliban government” in Kabul. “It is our mistake” that we did not do so.

He says Afghans have protested over border fencing and have also resorted “to open[ing] heavy fire on us”. But, he adds, “we are determined to fence” the border. “We have suffered a lot during the last 20 years due to this border. All the terrorists and miscreants have been infiltrating Pakistan through this border because it was open for anybody who wanted to come to this side,” he says, without wanting to be identified by name because of the sensitivity of the issue. “If 50,000 people come from Afghanistan daily for business and jobs, we do not know how many of them go back.”

Dr Timothy Nunan, assistant professor at the Center for Global History, Free University of Berlin, and author of the 2016 book Humanitarian Invasion: Global Development in Cold War Afghanistan, believes debates about the Durand Line are laden with emotional and fundamentally political ideas about the character of the Afghan state. “Since as early as the 1930s, but especially since the 1950s, Afghan intellectuals and governments have promoted the idea of Afghanistan as a Pakhtun state with responsibilities towards Pakhtun and Baloch groups in the territories east of the Durand Line. For this reason, Afghanistan … for decades championed the formation of an independent ‘Pakhtunistan’ [consisting of] Balochistan and NWFP.”

Nunan says Pakistan has had its own specific sensitivities about the role of Pakhtuns in the state. “Consider, for example, debates before the [recent] census about the number of Pakhtuns in Karachi, Quetta or Balochistan, or about the administrative future of Fata.”

But he points out that Pakistan’s attempts to resolve a political problem with an infrastructural solution – erecting a fence on the border – will weaken its case to defend its legitimate domestic security interests. “By inflaming nationalist sentiment in Kabul, the unilateral decision to build the fence makes it impossible for elements within the Afghan government to make unpopular decisions that could lay the groundwork for improved relations — for example, a closure of Indian consulates [in Afghanistan] and recognition of the Durand Line.” The fence, he says, will likely only boost the Afghans’ conviction that closer ties with India and nationalist rhetoric are their best tools for dealing with Pakistan.

Nunan suggests the only sustainable solution that Pakistan may have will be found through engaging Afghanistan in meaningful dialogue. “However intractable the debate may seem, it is worth reflecting that in the late 1970s, Mohammad Daoud Khan made serious efforts to settle the border with [Pakistan’s prime minister] Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. This process ended with the murder of the former in 1978 and the arrest of the latter in 1977 but it does perhaps offer a precedent for high-level diplomacy.”

Additional reporting by Namrah Zafar Moti

In response to the above article the Ministry of Foreign Affairs sent the Herald the following letter:

The people of Pakistan and Afghanistan enjoy centuries old bonds of shared history, culture and religion. Pakistan has always encouraged and facilitated people to people contacts between the two countries. Our current efforts of border management do not envisage hindering the movement of legitimate travelers, rather, our efforts would encourage and ensure safety and security of people travelling between the two countries.

Our efforts of better border management are geared towards curbing the cross border movement of terrorists, clamping down on traffickers and smugglers, enhance trade, transit and facilitate movement of people. We therefore, are upgrading infrastructure at our existing custom terminals to enhance their capacity to process larger quantities of goods and transiting vehicles and swift and convenient clearance of people.

[In response to the question posed regarding] the steps that Pakistan is taking to ensure that the fencing of the border does not harm or hamper the traditional family links between the Pakhhtun tribes living on its two sides, Pakistan has always encouraged and facilitated people to people contact between Afghanistan and Pakistan as we understand that such interactions solidify our bilateral relations. We are aware of ground realities and have undertaken multiple steps to ensure that life of common citizens on both sides of the border are not adversely affected by our initiative of effective border management.

Afghan students who attend schools on Pakistani side of the border have already been issued with RFID cards and a proposal to extend similar facility to the common people along the border is currently under consideration. A system of facilitative visas for medical treatment by Pakistani missions in Afghanistan is already in place and we are also working on a proposal to introduce a visa on arrival for those requiring urgent treatment at Torkham, Chaman and other border points.

[In response to the question posed regarding whether the people living in the border regions will be] taken into confidence over the border fencing and other border management mechanism, especially considering that there are still people present on both sides who see the Durand Line as an arbitrary, controversial line drawn by the British colonial rulers, the Government is fully mindful of the sentiments of the people living in the vicinity of both sides of the border and the social connections that exist between them. Therefore, it remains our endeavour that border management measures take into account this aspect and that we try to make the legal travel and trade easy but block the movement of terrorists and other undesired elements. People living along Pak-Afghan border understand the importance of these measures and they stand-by our efforts of effective border management.

[In response to the question posed regarding talks going on between Pakistani and Afghan security forces on border management], all issues of mutual concern are discussed in our bilateral consultations with Afghanistan. As far as the security forces are concerned there exits a hotline between the DGMO’s of the two countries and the channel is utilised to address Pak-Afghan border issues. Recently, the representatives of the two security forces met in Peshawar to discuss issues related to Pak-Afghan border security to the etc. We believe that the border management measures are mutually beneficial to the two countries as they would check movement of terrorists and smugglers, encourage and enhance bilateral trade and transit of Afghan merchandise to other countries and also facilitate and make the journey between the countries safe.

[In response to the question posed regarding] Pakistan considering any options/proposals to manage/control its border with Afghanistan in such a way that it does not negatively impact bilateral trade, Pakistan hasn’t introduce any restrictions for legal trade between Pakistan and Afghanistan, rather we are reinforcing and upgrading the existing trade terminals with the aim to increase their capacity, make them more efficient, also, we are exploring new trade terminals/crossing points to facilitate trade/transit and encourage legal movement of people and goods. We have recently opened a new border crossing for trade and transit of vehicles, at Kharlachi, Kurram agency. In addition we are investing in human resource as well as technical surveillance means to increase our reach to frequented and unfrequented routes used by smugglers and other undesired elements to curb illegal trade and smuggling. With these efforts we are hopeful that the trade between the two countries would increase and the traders of the two countries would be facilitated.

This was originally published in the Herald's September 2017 issue under the headline 'The thin red line'. To read more subscribe to the Herald in print.

The writer is a staffer at the Herald.