The 2018 elections have changed Pakistan’s political landscape and power structure from what they were till less than three months ago. Those in the government till recently are now gearing up for agitation and those who have been protesting since 2013 are now preparing themselves to take over the government.

All the losing parties are crying foul and some of them are calling for the election results to be countermanded. This is unlikely to happen. Nor would democratic opinion wish the confrontation on the electoral process to continue for long. The ground reality is that a regime change has taken effect. By the time these lines appear in print, Imran Khan should be getting ready to take oath as Pakistan’s new prime minister.

His victory speech, widely described as splendid rhetoric, has already won him considerable goodwill at home and abroad. He said many things that people, especially the poor and all those who feel strongly about corruption and extravagance by public representatives, wanted to hear. One of the main things missing was that the captain of the victorious team forgot to pay customary tribute to the losing side for putting up a good fight.

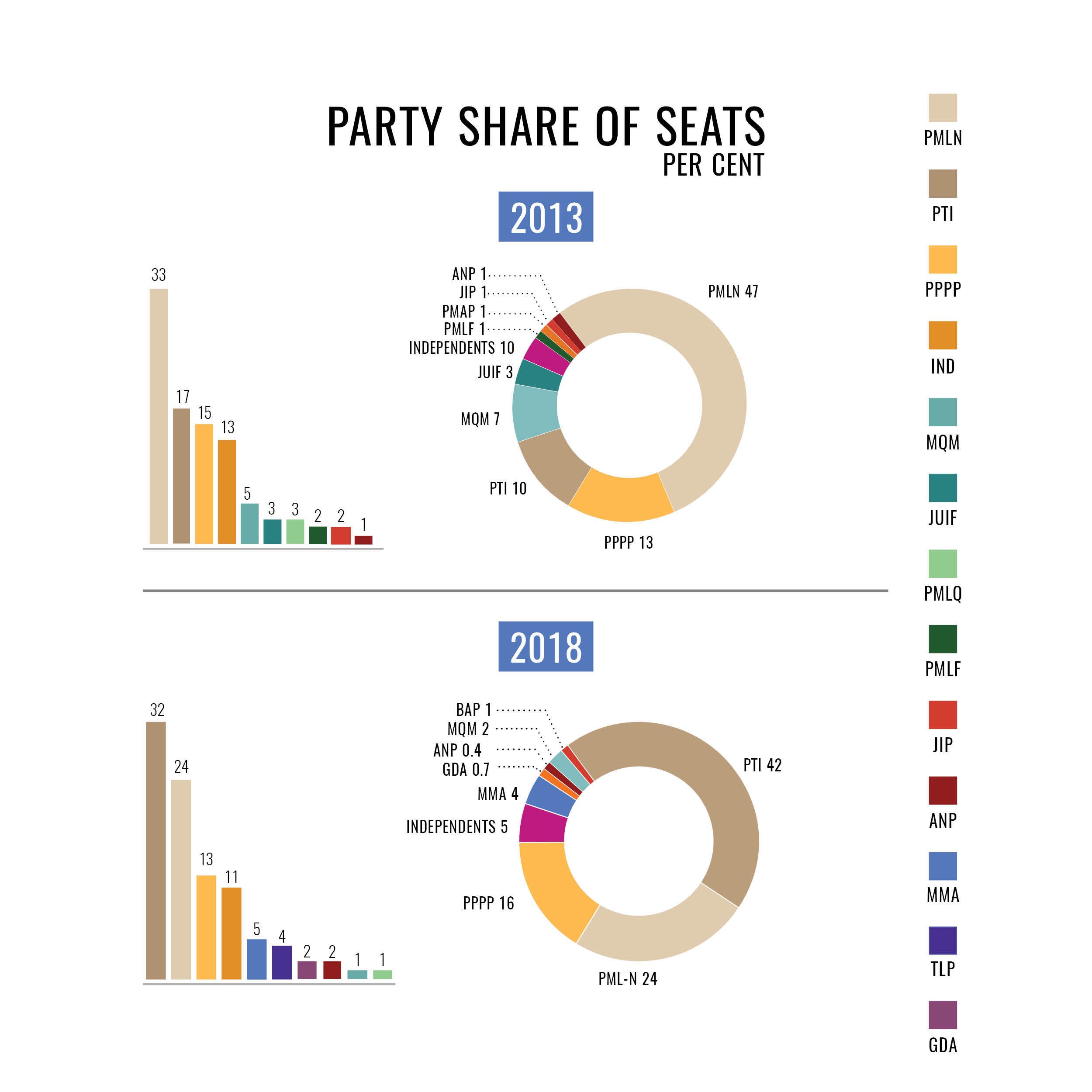

Going back to the election results, the final tally proved most political pundits wrong as Imran Khan’s Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) won more seats in the National Assembly than its main rival, Nawaz Sharif’s Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PMLN), did. Even in the Punjab Assembly, the former party fell only a few seats short of the latter. PTI also suffered no incumbency disadvantage in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and surprised everybody by bagging more seats in Karachi – both for the National Assembly and the Sindh Assembly – than the Muttahida Qaumi Movement-Pakistan (MQMP) and the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) put together.

PMLN won fewer seats in the National Assembly as well as in the Punjab Assembly than most observers had predicted. These observers perhaps could not fully assess the pro-PTI environment created prior to the polls and the impact of Imran Khan’s aggressive campaigning.

Still the credit due to PMLN for its plucky fight should not be held back. It entered the electoral arena with its hands and feet tied – though the fact that it was on the rack matters less than its actual electoral position – and yet it raced neck and neck against the odds-on favourite. In the end, it got seats in the National Assembly commensurate with its share of the popular vote — winning 23.7 per cent of all the contested seats with 23 per cent of polled votes. Compared to this PTI won 43 per cent share of the National Assembly seats with a 31 per cent share of polled votes. This is likely to revive the on and off debate on the shortcomings of our first-past-the-post electoral system.

Much noise had been made about the importance of ‘electable’ candidates in the run-up to the election but all assessments in this regard were largely proved wrong. The candidates acquired by PTI from other parties on the assumption of their electability generally failed to do well.

Many of them – including former Punjab governor Sardar Zulfiqar Ali Khan Khosa and former PPP bigwigs Nadeem Afzal Gondal, Nazar Muhammad Gondal and Firdous Ashiq Awan – could not win their seats. Quite a few PTI candidates who were given party tickets on the basis of their electability lost to the party’s own supporters who had been denied election nominations.

Some of the heavyweights (such as former interior minister Chaudhry Nisar Ali Khan and Prince Abbas Khan Abbasi, a descendant of the Nawab of Bahawalpur), who considered themselves unbeatable on the strength of their personal standing, entered the fray as independent candidates and fared badly. This strengthens the impression that political parties in this election have mattered more – just as they have done in the past – than individual candidates. This can be considered a good omen for a transition to democracy though the way political parties have frittered away such advantages in the past dampens such optimism.

What does not look good is that the competition between political parties and candidates for citizens’ votes often degenerated into hateful encounters and permanent-looking divisions in society. Instead of winners shaking hands with losers and the latter congratulating the former, the competing camps have passed on the baggage of mutual hatred and enmity to their supporters in the larger communities. This is closer to the tradition of vulgar feudal feuds than to a decent democratic competition.

The result is incidents like the arrest of two young men in Bannu for allegedly shooting a dog after draping it in the flag of a party that they opposed. The harm that such perpetuation of electoral enmities causes to politics, public administration and cultural life is truly enormous. All parties have a duty to develop a culture of respect for their opponents.

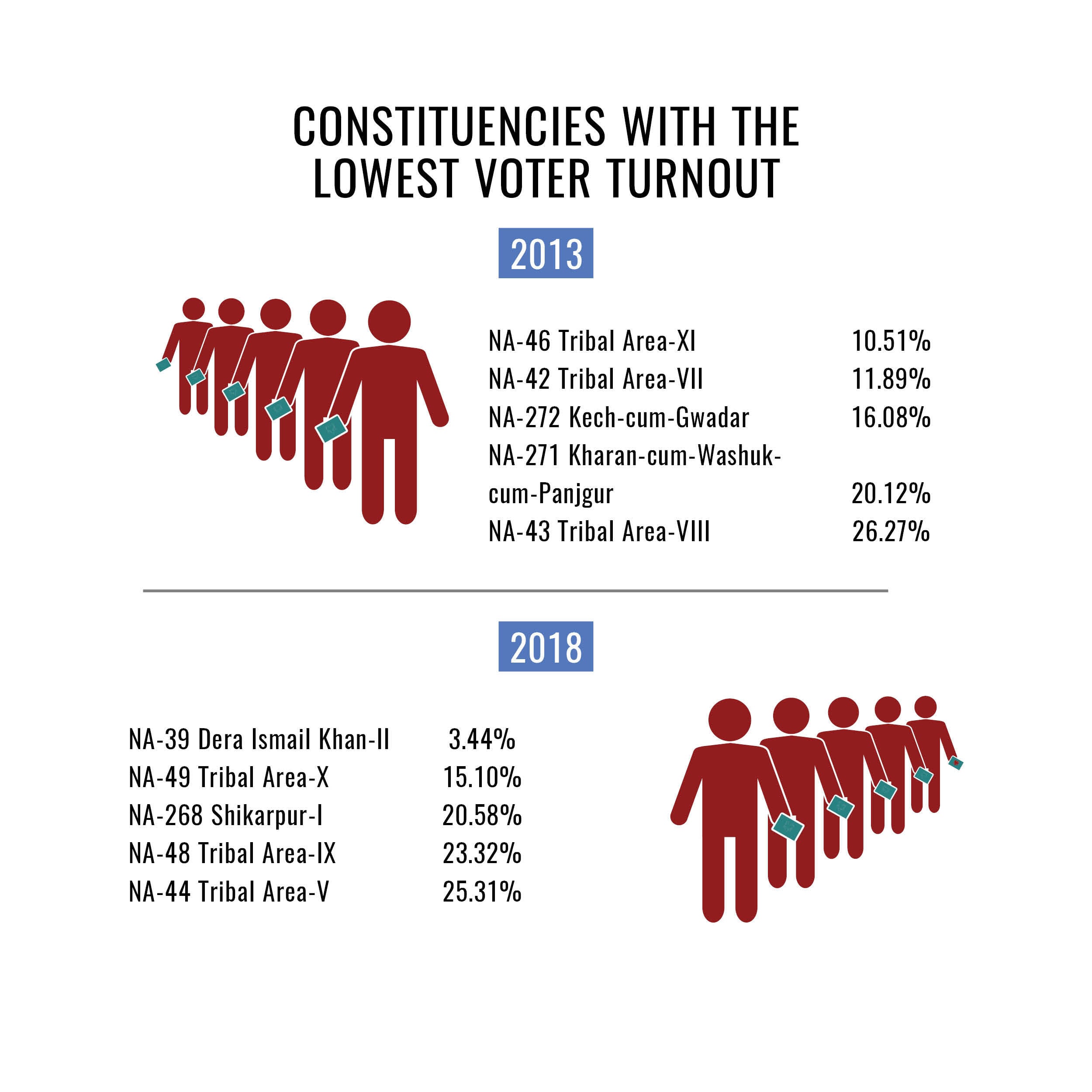

There were signs of genuine public participation in polling in Balochistan in terms of the voter turnout after several general elections. In the National Assembly constituency that spans over the districts of Lasbela and Gwadar, the winner and the runner-up both polled more than 60,000 votes which is a record for Balochistan. The voter turnout in this constituency was more than 56 per cent, around four percentage points above the national figure.

A new political entity, the Balochistan Awami Party (BAP), created after the Senate election earlier this year, did well and emerged as the largest single group in the provincial assembly though it did not do equally well in the elections to the National Assembly. And Shahzain Bugti, who won a National Assembly seat from his ancestral Dera Bugti district, was given to believe that his claim to be the political heir to his slain grandfather Nawab Akbar Bugti could be accepted. One would have felt happier if some understanding with the dissident Baloch nationalists had also been reached.

The other major positive development was that election candidates included a large number of women who contested general, rather than reserved, seats for both the National Assembly and the four provincial assemblies. This could be due to the legal requirement that made it compulsory for all political parties to grant at least five per cent of their election nominations for general seats to women. Some of these candidates had contested elections earlier as well but they were outnumbered by those who ran for the first time.

Out of all these, eight have become members of the National Assembly (four from Sindh, three from Punjab and one from Balochistan). Nine others have won provincial assembly seats. This is an improvement upon the 2013 figures (when only six women won seats in any of the five directly elected legislative forums) and slightly better than the 2008 number (when women secured 16 general seats) and 2002 results (when they won 13 general seats).

The growing acceptance of women as people’s representatives on general seats ought to be welcomed as a progress towards the deepening and strengthening of democratic norms. That a majority of the women candidates belonged to politically known and influential families does not matter. If the transition to democracy continues unhindered, women from the lower rungs of society might also start winning seats in the legislatures.

There was some good news for members of minority communities too. Dr Mahesh Malani became the first Pakistani Hindu, after 1970, to be elected to the National Assembly from a general seat. He had been elected to the Sindh Assembly from a general seat in 2013 and had won recognition as a conscientious and diligent legislator. Two other Pakistani Hindus – one from Jamshoro district and the other from Mirpurkhas district – also won seats in the Sindh assembly from constituencies that have large Muslim majorities.

The credit for consolidating the system of joint electorate and secular politics through this small but significant development can be claimed by PPP. The party has also enabled the first Pakistani woman of African descent to enter the provincial assembly of Sindh by nominating her on a reserved seat. Similarly, PTI deserves credit for getting a member of the Kalash community, Wazir Zada, into the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Assembly by including him in its list of nominees for the seats earmarked for minority communities.

Also welcome was the ability of the Hazaras of Quetta to maintain their presence in the Balochistan Assembly. One of the beleaguered community’s own political entities, the Hazara Democratic Party, has won two seats in the house (though the winner of one of these seats has been barred from taking oath as a legislator unless he can prove that he is a bona fide Pakistani citizen and not an Afghan refugee).

The defeat of many political stalwarts in the election needs to be pondered over. The media has only sensationalised their ouster from Parliament but there are other aspects of their failure to make it to the assemblies which should not be ignored.

The absence of Chaudhry Nisar Ali Khan, Pashtoonkhwa Milli Awami Party (PkMAP) chief Mehmood Khan Achakzai, the head of Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam-Fazl (JUIF) Maulana Fazlur Rahman and top Awami National Party (ANP) leaders such as Asfandyar Wali Khan and Ghulam Ahmed Bilour will make the Parliament poorer as far the quality of its debates and legislative battles among its members are concerned. One would have included Jamaat-e-Islami (JI) emir Sirajul Haq in this list as well but he has retained his seat in the Senate so he can have his say there.

The case of Mehmood Khan Achakzai and Fazlur Rahman deserves special notice as they – the former more than the latter – are known for defending the supremacy of Parliament and for presenting a democratic perspective on the crucial issue of imbalance in civil-military relations. If they have been punished by the voters – or by someone else – for espousing such views, Pakistan is the loser.

The religious-political parties that had banded themselves together under the banner of the Muttahida Majlis-e-Amal (MMA) suffered a loss of face as they got one less National Assembly seat than they had won separately in 2013 when JUIF had secured 10 seats and JI had won three. They were not able to pose any challenge to PTI in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. It is possible that they did not have the external support they had in the 2002 elections when General Pervez Musharraf was working out his thesis on the unity of command in the electoral arena.

It is also possible that this time it was deemed necessary to test the strength of some new religious groups. One of them, the Tehreek-e-Labbaik Pakistan, that emerged in 2017 and staged a successful blockade of Islamabad the same year, has reason to be happy with its showing in the 2018 elections. It won two provincial assembly seats in Sindh – both from Karachi – and polled more than 1.8 million votes in Punjab and around 400,000 votes in Sindh.

The containment of parties in MMA, the free run allowed to the Tehreek-e-Labbaik Pakistan and the permission granted to members of banned sectarian and militant outfits to contest the polls by adopting a registered party as the vehicle for satisfying their electoral ambitions could have serious repercussions for the polity. Moderate voters supporting the MMA’s constituent parties could come under pressure to join outfits like the Tehreek-e-Labbaik Pakistan or other new and more militant organisations. One wonders whether such a development will be in the interest of a democratic consolidation in the country.

Significant changes have taken place in Sindh’s political landscape if one were to take the election results at their face value. PPP managed to beat off the challenge from the Grand Democratic Alliance (GDA) in the province’s interior and it increased its share of the National Assembly seats from Karachi — from one in 2013 to three in 2018. Yet it could not prevent PTI from recording extraordinarily high gains in Karachi. PPP will run into greater troubles if it fails to read the winds of change properly. For the time being, it will retain its hold on the provincial government in Sindh but PTI, that has the second largest number of provincial assembly seats, will be a formidable opposition and more so if it also takes GDA under its wings.

A change in the strategy of Sindhi nationalist and other ethno-political groups in Sindh cannot be ruled out. Instead of challenging PPP with their own strength within the province, they could seek the patronage of the new PTI-led political elite in Punjab that will not only be in power at the federal level but also seems to be in the good books of the establishment. PTI has already thrown a bait to MQMP (the party it has dethroned in Karachi) — and MQMP seems keen to bite that bait. With its slim majority in the Sindh Assembly, PPP may have to face tough competition from an opposition alliance of around 45 members.

If, with federal support, PTI can satisfy even a fraction of the yearning among Karachi’s citizens for relief from mismanagement and corruption, its challenge to PPP all over Sindh could increase enormously and PPP might find itself in serious trouble during the next general election. An additional worry for the party will be the accountability drive against its top leadership that has already gained renewed momentum. One cannot say how it will fare under pressure from such a drive.

Another party that is seriously threatened by PTI’s rise in Karachi is MQMP. Pakistan’s largest and only post-feudal city has embraced PTI in a big way as its representative, electing its nominees to 14 of its 21 National Assembly seats and 21 of its 44 provincial assembly seats. This could mean the beginning of the end of muhajir politics as conducted since MQM was founded under the patronage of General Ziaul Haq’s military dictatorship.

MQMP has certainly paid a price for the immaturity shown by the leaders of its warring factions and there may be some truth in their complaints of interference in election by unmentionable elements, but its leadership will do well not to attribute its stunning defeat to these two factors alone. It must carry out a realistic appraisal of its political strategies, especially its reliance on the stagnant politics of narrow ethnic identity and on securing the Urdu-speaking community’s following allegedly through fear, intimidation and violence. If MQMP cannot evolve a new and democratic thesis and persuasive methods of winning friends, it should be prepared for even harder tribulations.

Another challenge for both PPP and MQMP comes from the Tehreek-e-Labbaik Pakistan which, quite obviously, has found support among Karachi’s lower and middle classes whose amenability to populism in religious rhetoric is well-known. The party’s ability to challenge the city’s other political stakeholders is likely to grow with the passage of time.

No discussion on a general election can be complete without an assessment of the performance of the Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP). The conduct of the 2018 election leaves a lot to be desired on this count.

The election was conducted under a new law, the Elections Act of 2017, which was formulated on the basis of recommendations by a large parliamentary committee set up in 2014 with the express objective of suggesting much needed reforms in the election system. Leaving aside controversies over the long time taken to draft the law, more attention was paid after its passage to the agitation by religious parties over changes in some mandatory declarations by election candidates than to the many not-so-good features of the new law or any of its significant omissions.

But the fact is that the new law gave election commission more powers to conduct elections than it ever had. For instance, it acquired powers to annul the polls in any constituency if the number of votes cast by women voters there fell below 10 per cent of the registered women voters. The commission was also empowered to regulate election expenses and ensure that women and members of minority communities were fully enrolled as voters and represented as candidates. (The law, however, did not extend the benefit of joint electorate to the members of the Ahmadi community and that continues to detract from the state’s claims to be a genuine democracy.)

Even more significantly, the law gave election commission sweeping powers to regulate the working of political parties. These powers included the mandatory registration of political parties with the Election Commission of Pakistan in order to be eligible to contest elections — a condition that was struck down by courts in 1988.

Still it was a stupendous task even for an empowered election commission to hold elections for the National Assembly and the four provincial assemblies simultaneously on a single day. The commission deserves credit for carrying out the technical part of the election exercise fairly well but some of its decisions did not satisfy democratic opinion.

Firstly, the Election Commission of Pakistan assigned unprecedented responsibilities to the military which was fair neither to the cause of a free and democratic election nor to the military itself. As is being alleged, it was not possible for election officials to ensure that the job of security forces was limited to just the maintenance of order during polling.

Secondly, election authorities failed to accord equal importance to all the political parties. As a large number of people were still waiting to cast their votes outside polling stations when voting hours ended, mainly because the vote casting process was manifestly slow, several parties pleaded for extension of polling time by one hour.

The only party that did not support this demand was PTI though those waiting in queues must have included its supporters too. Heavens would not have fallen if polling had been allowed to continue for another half an hour or so. A similar request by PTI for an extension in voting time by an hour, on the other hand, had been readily granted days before the polling.

In the Election Commission of Pakistan’s defence, it can be argued that the Elections Act, 2017 does not make very clear provisions as far as changes in polling hours are concerned. Since such questions may arise in the future too, it may be useful to refer to relevant provisions of the law.

Section 70 of the act deals with hours of the poll. It says: “The Commission shall fix the hours, which shall not be less than eight, during which the poll shall be held and the returning officer shall give public notice of the hours so fixed and hold the poll according to the hours fixed by the Commission.”

This section does not refer to the possibility of changing the polling hours after they have been fixed probably because the matter is covered by a proviso which says: “Provided that the Commission may extend polling hours in one or more polling stations in exceptional circumstances to be recorded in writing but such decisions shall be taken at least three hours before the close of the poll, enabling the returning officers to convey the decision of the Commission to all presiding officers under his jurisdiction well before the time already fixed for close of the poll.”

The flawed text of the proviso seems to be the cause of confusion as the need to extend polling time is usually felt during the last hour. Nobody can, in most cases, decide the matter three hours earlier than that. This flaw is especially glaring given that returning officers can now communicate with presiding officers by just pushing a single button on their mobile phones.

It should be possible to resolve the matter by appropriately amending Section 70 of the act.

The other, and frequently heard, complaint about polling was its slow pace. All poll observers have confirmed this. European Union observers have attributed the long time taken to cast a vote to the procedure introduced by the Election Commission of Pakistan. Sometimes the shortcomings of the staff borrowed from provincial government departments for polling day were to be blamed for the slow voting process. In any case, a proper probe will be in order.

There was only one entrance to five polling booths at the Fatima Jinnah Medical College in Lahore where I was able to cast my vote, thanks to a helpful presiding officer. Voters had to stand in lines for hours. The polling staff and polling agents were sitting cramped in small and inadequately lighted rooms. Some polling booths were reported to be without any fans — a major inconvenience for both the voters and the staff in stifling July heat. These matters could have been taken care of by wide awake assistant returning officers (usually taken from the provincial administration, educational institutions and banks, etc).

This brings us to the question of the quality of services rendered by the staff acquired for the election. Their assignment demanded proper motivation and some degree of commitment to democratic ideals. Those who thought they were being made to do forced labour or those who complained of inadequate reward or lack of regard were unlikely to be duly useful. The Election Commission of Pakistan will do well to streamline its training programmes for election staff and also by scouting for motivated and efficient talent outside its limited pool of government officials.

A greater confusion was caused by the failure of the result transmission system (RTS) than from the ineptness of polling staff. When results stopped getting routinely updated, even from the constituencies in major cities such as Lahore and Karachi, people suspected the worst. They did not understand why the results were being delayed in the presence of a sophisticated electronic system put in place for the direct transmission of vote counts from polling stations to the Election Commission of Pakistan’s headquarters in Islamabad.

This was perhaps the result of acquiring a software too delicate to be properly handled by semi-skilled hands available at both ends. No surprises there. In Pakistan, old hands often take more time composing their reports on computers than they used to take while writing them in long hand and most people supplied with computers use them only as typewriters. It should be possible to make RTS fully operational during the coming by-elections in order to test it thoroughly and remove the flaws in its working as well as its handling.

Another sticky problem on the hands of the Election Commission of Pakistan was the handling of political ambitions of those associated with banned religious and sectarian outfits. Many of them had taken refuge inside parties that were already registered. There were few restrictions on their attempts to highlight their association with banned groups as a means to attract voters. At least one television advertisement stated candidates contesting elections under a particular symbol enjoyed the support of a banned group. It was only later that the reference to the banned entity was dropped in the advert.

The Election Commission of Pakistan considered itself bound to allow anyone holding a registered/enlisted party’s ticket to join the electoral contest. Maybe the law needs to be amended to deal with parties found involved in terrorist activities after they have been registered or enlisted but one would not like to press the point hard in view of a possible abuse of the law’s restrictive provisions.

Another issue that calls for urgent attention from both the government and the Election Commission of Pakistan relates to the high number of rejected votes. That in this election 1.67 million votes – more than three per cent of the total votes cast – were rejected and that in more than 30 constituencies the rejected votes exceeded the margin of victory is more serious a matter than a mere scandal. Obviously a much greater investment needs to be made in raising awareness among citizens about political and electoral subjects. Civil society organisations can offer meaningful help in this regard provided the state can shed its irrational hostility towards them.

Above all, the Election Commission of Pakistan can be an efficient and fair-minded institution only to the extent that Parliament can provide for through legislation. The need for Parliament and the public to go on improving the electoral framework is manifest.

This was perhaps the most expensive election in Pakistan’s history, mainly due to an excessive use of television for publicity campaigns by political parties. The Election Commission of Pakistan says it has taken note of the high-cost television advertisements and these were being monitored during the election but there is little that it can do beyond that.

The Elections Act, 2017 provides that a National Assembly candidate cannot spend more than four million rupees on canvassing voters. The expense limit for a provincial assembly candidate is two million rupees. Most of the candidates, however, spent way more than these amounts and sometimes out of sheer necessity. For instance, polling staff refused to entertain voters unless they brought a slip carrying their vote number and other identification details. These slips were available at the camps run by various candidates and often the expense on setting up these camps alone could have approached the expense limits imposed by the law.

To reduce election expenses so that people of modest means could also join the electoral race, the Supreme Court of Pakistan had issued a verdict in June 2012 on a petition filed by Abid Hassan Minto. The verdict had restricted candidates to use only a specially opened bank account for making all election-related expenses. The amount of money spent through this account could not exceed the relevant expense limit given in the law.

In theory, this restriction allows the Election Commission of Pakistan to monitor a candidate’s expenditure more easily than it could earlier. One, however, doubts if effective mechanisms have been put in place to ensure that no expenses are made from other accounts or by other individuals on behalf of a candidate. It is generally believed that a large number of candidates succeed in concealing their actual election expenses by making them through other persons and, for a variety of reasons, the Election Commission of Pakistan is unable and incapable of proceeding against the offenders.

The election expenses of a candidate under the law do include, in addition to money spent by himself, “the expenses incurred by any person or a political party on behalf of the candidate”. A candidate is required to include in his expense account any expenditure incurred by a friend/supporter on “stationery, postage, advertisement, transport, or for any other item”. But these limitations are yet to be enforced fully.

Where the law is almost silent is on money spent by political parties on their collective campaigning. Unfortunately, the authors of the Elections Act, 2017 did not heed persistent public demand for putting in specific restrictions on election-related expenses incurred by political parties which tend to believe they are free to spend as much money as they can on advertising and other propaganda material. They also think that they do not have to worry much about the sources that money is generated from.

In a broader sense, however, they are not as free in making these expenses as they may like to believe. Each year, they are required to submit their audited accounts showing their annual income and expenditure, sources of funds, and assets and liabilities. They are also required to submit to the Election Commission of Pakistan details of their expenses during a general election as well as the names of all those who have given them 100,000 rupees or more for an election campaign.

Although the language of the relevant section of the Elections Act, 2017 – Section 211 – is somewhat obscure, in as much as it does not refer to the total amount of contributions received by a political party, it should be possible for the Election Commission of Pakistan to ascertain how much money a party had before an election and how much money it acquired for its election campaign and from where.

Given the various shortcomings of the election law, it is also not possible to proceed against extravagant candidates/parties. What, however, can still be done is that information about all campaign expenses should be made public in order to increase the level of electoral transparency. People should know how the means of ruling over them have been acquired.

The question whether the 2018 elections were free and fair needs to be answered in three parts corresponding to the pre-poll environment, the process of polling and post-polling developments.

There is little doubt that the pre-poll environment was tilted heavily in PTI’s favour because its main rival, PMLN, had been in the doghouse for a pretty long time. Its leader had been ousted from the prime minister’s office, disqualified for life and eventually sent to prison. It could not escape the effects of a media-propelled corruption narrative against its leadership. The timing and the nature of court decisions against some of its prominent members, such as the imprisonment of its National Assembly candidate Hanif Abbasi in an anti-narcotics case and the electoral disqualification of its former minister Daniyal Aziz on contempt of court just before the polls, also went against it.

As against this, PTI was drawing strength from its crowd-pulling capacity. It was also being backed by a greater part of the media, especially television news channels. A preponderant majority of the people believed that PTI in general, and Imran Khan in particular, enjoyed the patronage of the most powerful elements in the establishment. The military has firmly denied any involvement with electoral politics but, perhaps, people still believed what they wanted to believe and concluded that the pre-election environment was not neutral.

The frequency of migration of outgoing legislators to PTI was above normal for a pre-election period and stories in circulation suggested that many of them had been persuaded to change their party labels by persons in authority.

Additionally, while PTI faced little problem in holding meetings and rallies anywhere in Pakistan, the leaders of PMLN had difficulty in organising and addressing public meetings in many parts of the country and PPP leaders, including its chairman Bilawal Bhutto-Zardari, were not given clearance even to enter their own constituencies. It was difficult to reject the impression that the electoral process was being managed by elements capable of doing so. This impression was just another way of describing pre-poll rigging which the people of Pakistan are quite familiar with.

Polling day was by and large peaceful though a powerful bomb blast outside a polling station in Quetta took as many as 31 lives. There were also a few other incidents of violence before the polls. Two suicide bombings in Peshawar and Mastung, for instance, resulted in the killing of two election candidates along with more than 130 others.

The casting of votes could be described as fair but there were issues that vitiated the climate required for a free polling. Arrangements for prisoners and physically challenged voters were not adequate. Other voters were strictly told to secure their vote numbers from the camps set up by candidates — a practice that infringes upon the secrecy of voting. Those who went to polling stations with information obtained through an SMS service run by the Election Commission of Pakistan were more often than not told to go back and bring with them slips from the candidate camps. Those armed with slips issued by a particular party had smoother sailing in the polling booth than holders of slips from other camps.

Also, contrary to the declarations by the Election Commission of Pakistan, military personnel were present within polling booths. Although they treated the voters with courtesy, their presence where the law prohibited them from being present was contrary to the requisites of a free polling. Indeed, the only people completely free and relaxed at many polling stations were policemen who whiled away their time near the gates of polling stations or somewhere else in the shade. Some of them thanked the military for saving them from standing guard in rooms where heat and humidity would make breathing difficult.

The situation changed for the worse after the close of polling. Many candidates complained that their polling agents were thrown out of polling stations during the counting of votes and tabulation of results and that Form 45 – that recorded the detailed vote count at each polling station – was neither given to their agents nor was it put on the Election Commission of Pakistan’s website. These complaints and the rejection of a large number of ballot papers constitute the core of the clamour about what is being seen as a large-scale post-poll manipulation of voting outcomes.

In his victory speech, Imran Khan laid considerable emphasis on austerity. He reiterated his aversion to staying in the Prime Minister House and his ideas of turning the various governor houses into universities. Both are hugely popular ideas but not necessarily as beneficial as is generally assumed.

The idea that holders of high political office in a poor country should practise austerity is embedded in our political tradition. Those who ridicule Gandhi’s decision to wear the simplest possible dress, travel in third-class train compartments and live in scavengers’ colonies or the Indian political parties’ practice of conducting their deliberations while squatting on the floor as cheap political ploys should do well to reflect on the politicians’ need to identify themselves with the have-nots. Two of the most important members of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s first cabinet, Dr Mubashir Hasan and Sheikh Muhammad Rashid, never occupied bungalows requisitioned for ministers and chose to stay with relatives or friends in quarters for middle-tier civil servants. Quite a few Pakhtun political leaders prefer living simply even today. Imran Khan himself has derived benefit from the way he dresses for public functions — in clothes that do not appear too expensive or too formal.

But where a head of government lives is less important than what he does. All the occupants of the White House and 10 Downing Street are not known to have discharged their responsibilities equally well.

Likewise turning the governor houses into universities is less important than improving the overall performance of educational institutions and making quality higher and technical education affordable by the poor.

The real issue in Pakistan has been to overcome constraints to democratic governance and this did not receive due attention in Imran Khan’s first address. No Pakistani prime minister has enjoyed the freedom of action the high office requires. Indeed, all those who tried to be real prime ministers came to grief. How will Imran Khan maintain the authority and dignity of his office is something people are going to watch with much interest.

In addition, the new government will also be watched for making, or not making, efforts to shed practices associated with majoritarianism. It needs to move towards more participatory governance so that it can guide the country beyond the problems associated with the implementation of the 18th Constitutional Amendment and the last National Finance Commission award for the distribution of finances among the centre and the federating units.

Another area where the new government’s performance will be closely watched is economy. Even before PTI has taken over power, notice has begun to be taken of its likely resort to the International Monetary Fund for a financial lifeline. The new economic team, however, deserves to be given time to learn the ropes and acquire the ability to review and rectify mistakes of the past. Managing a country’s affairs and campaigning for gaining power are different ball games altogether. Imran Khan and his party will not be the first in history to adopt policies for which they have lambasted their opponents for years.

The immediate task for the incoming government, however, is to wind up as speedily as possible the issues generated by the general elections. Imran Khan did well to call for burying the hatchet and offer the reopening of as many boxes as necessary to address the grievances of losing candidates about unfairness of the polls.

In order to honour a national consensus on the need to move on, the phase of recounting of votes as well as hearing of election petitions must be completed as expeditiously as possible. No government should like to live with doubts about the legitimacy of its rule.

The writer is a senior journalist, peace activist and human rights advocate.

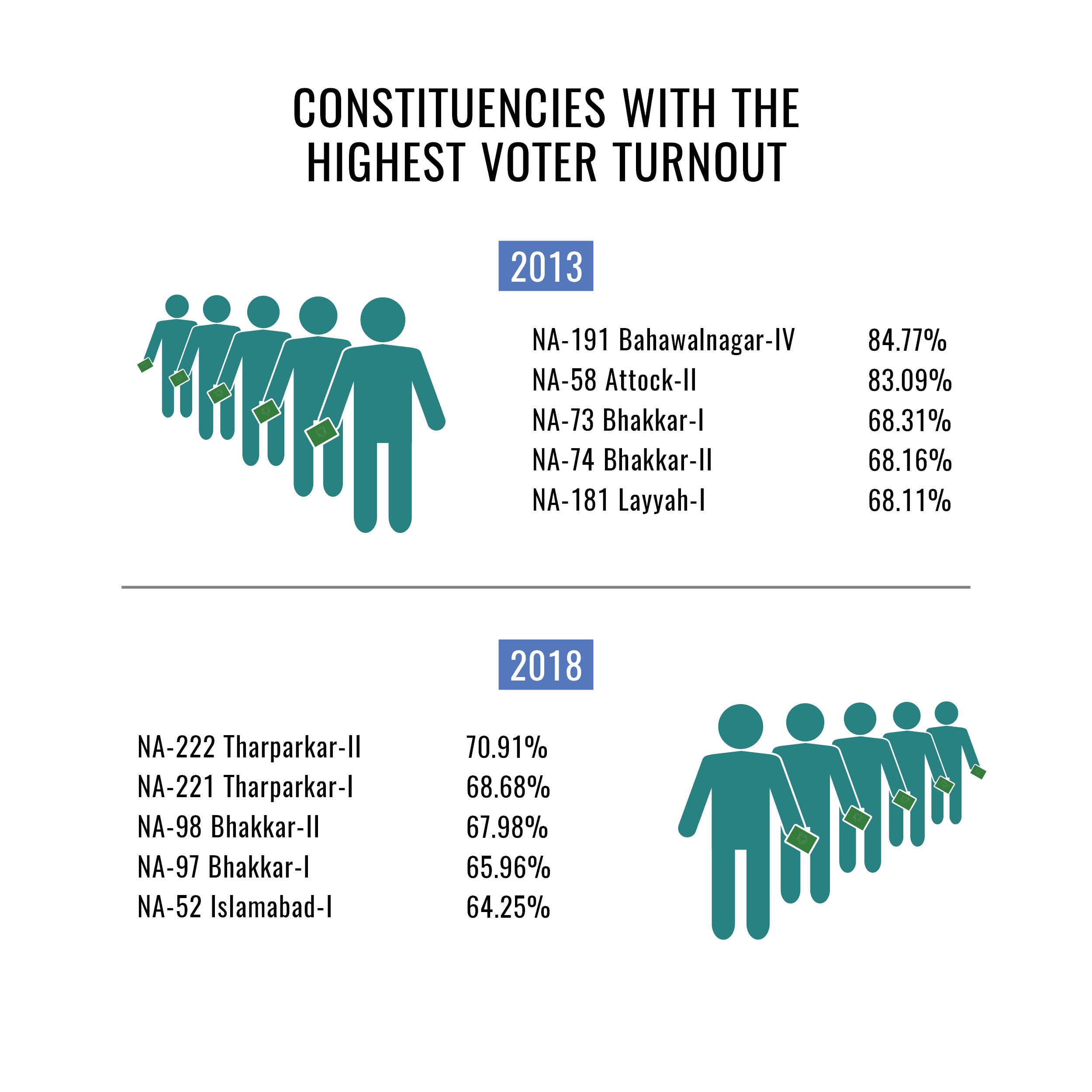

Graphs compiled by Aliyah Sahqani, Maham Hashmi, Hammad Motiwala, Mikhyle Anthony and Arnold Anthony using official data.

This was originally published in the August 2018 issue of the Herald. To read more, subscribe to the Herald in print.