Contemporary artists are increasingly unwilling to be categorised by the specific mediums they utilise in their practices. The boundaries between sculpture, painting and digital art are blurring as art institutions in Pakistan catch up with global trends. The outcome is a new generation of art school graduates who are not solely defined by a single skill or expertise. Like storytellers who simultaneously use description, narration and dialogue, these artists now employ a number of processes within the same artistic image. Whether their artwork represents reality is beside the point.

The distinction between two-dimensional and three-dimensional work is also getting blurrier and fuzzier as 21st century artists compulsively merge multiple forms in their art making. One no longer needs to move around a sculpture to observe it — a sculpture can be digital now. Paintings, too, need not be confined to framed surfaces hung on walls.

Curator and artist Alia Bilgrami recently brought three artists together to examine these newly emerging grey areas in an exhibition titled Folding Shadows. The show featured works that are inspired by perceptions of three dimensionality but realise those perceptions, each in its own way, through linear patterns, geometric designs and the layering and folding of materials.

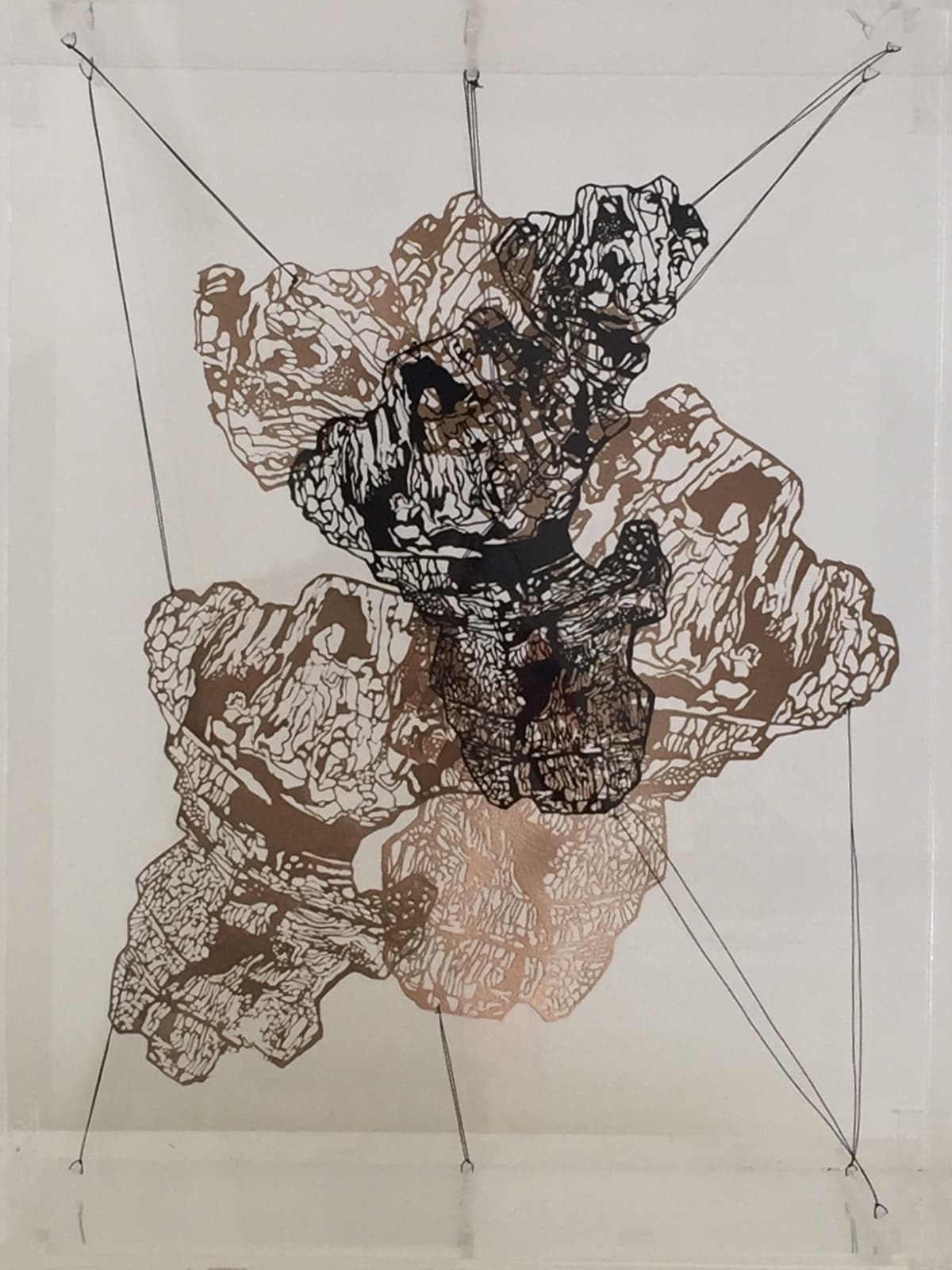

For instance, Sarah Ahmad uses detailed ink drawings of foliage and tree bark on thin sheets of vellum (leather parchments used as a writing surface) to highlight the intricacies of nature. Titled Fractured Cosmos of Driftwood, her compositions are made on a two-dimensional surface but one can feel the thickness of the bark as well as the multiple veiny threads wrapped around the stems.

It is interesting to note that Sarah uses monochromatic hues – black and white – to outline these images of nature. Without colour, the artworks appear more like scientific diagrams, examining the cellular composition of the bark and the plants.

In her artist’s statement, Sarah draws a comparison between experiencing nature and understanding the complex systems which make up the universe — systems that can both destroy and sustain life on Earth. She uses laser-cut pieces of her drawings to create installations around the walls of Koel Gallery, bringing inanimate patterns of nature to life through layering and scrunching of the vellum sheets. This appears to be an effort to highlight how nature adapts to, or at least bypasses, any conditions presented to it by human beings.

The second artist featured in the show is Hadia Moiz, who usually explores colour tones in her work through the use of negative space. Her works on display use light and shadow to create images within boxes made from Perspex (a transparent plastic material that can vary in thickness). These images use the shapes and silhouettes of such objects as an old-fashioned time capsule, drawers and a chess pawn to evoke confusion among viewers. Not only is there no single visual to focus on, but the artist is deliberately playing with misconceptions too.

Hadia also plays with the scale of the objects trapped in the Perspex boxes and prevents the viewer from having a clear understanding of their full form. This perhaps is a commentary on the complex realities of human life in the 21st century. As the curator points out in her curatorial note, the layering in Hadia’s work can be seen as an attempt to analyse the complications created by time as it passes by.

People often ask, “What can we really take away from art?” The question is especially pertinent here because contemporary art – mostly exhibited in restricted spaces such as galleries and museums – can be viewed by limited audiences. The short answer is that art always provides an opportunity to be imaginative, even to a passive viewer.

That is what Sarah and Hadia do. They channel light, objects and shapes in their work in such a way that viewers are able to see entire landscapes of expression in their art rather than looking at a single object, like a tree or a piece of furniture. The two artists take familiar objects such as leaves and trees or chess pieces and contort them to make them look like something far removed from reality, thus engaging viewers to tell stories that can include numerous details and have multiple meanings.

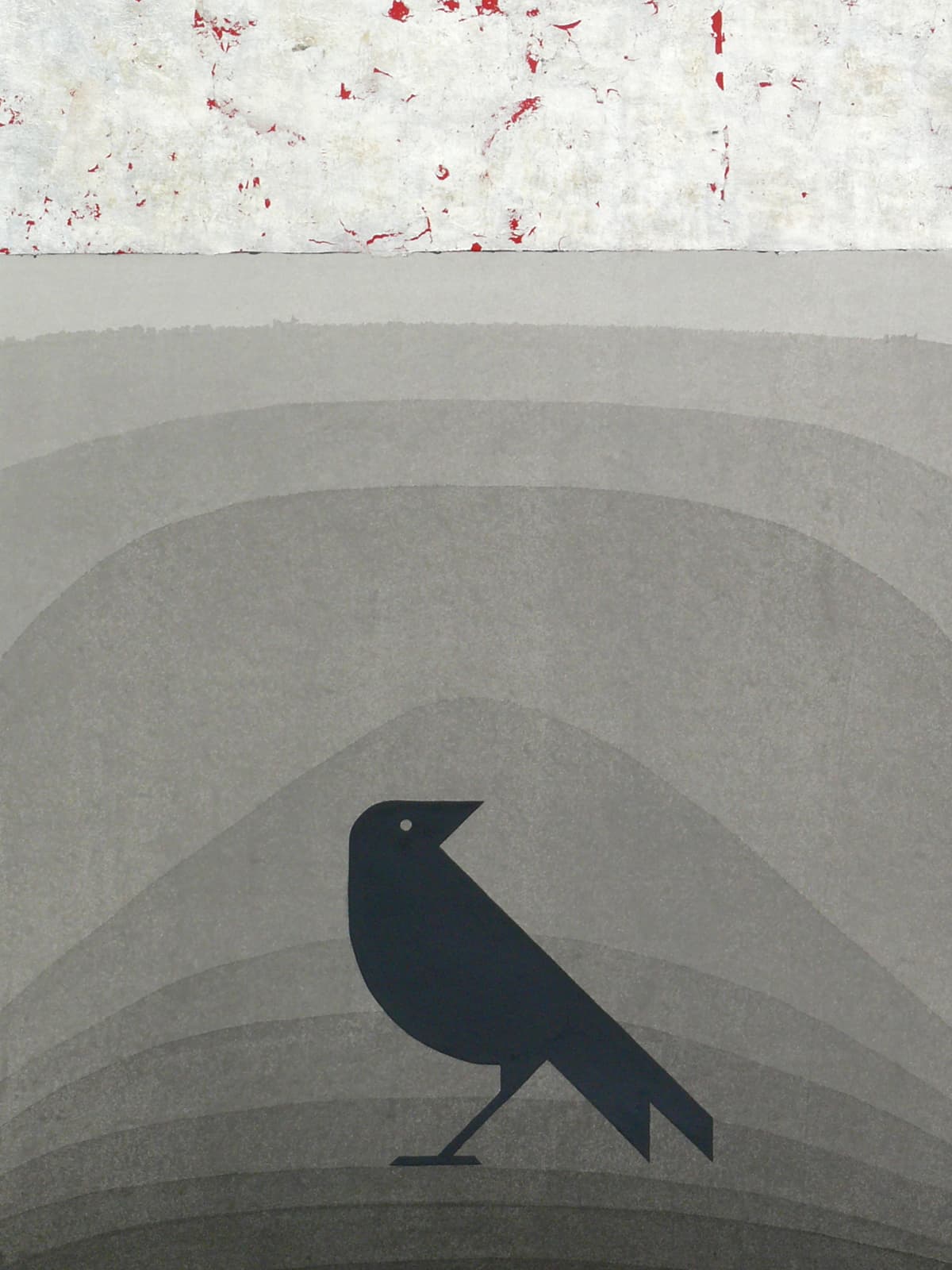

Babar Gull, the third participating artist in the show, similarly uses visuals we are all familiar with: the basic shapes of inanimate objects that remind us of our childhood. He uses triangles and rectangles painted with black Sumi ink to make a crowing bird, an upright sitting dog, a paper boat and a plane. These paintings are inspired by sculptural origami shapes, which could be misconceived as a childish pastime yet his rendition has made them look as though hours were spent to create them. His choice of medium – ink and the traditional Wasli paper – can be seen as a conscious decision to contrast his work with the toy-like images we all draw as children with pen on paper.

Gull’s pieces also investigate those methods and techniques that invite a discussion on how art is moving away from a single traditional process. Although he has painted images that even a small child can connect with, his usage of patient ink washes and detailing on unforgivingly sensitive Wasli paper suggest that he wants his viewer to look beyond the surface.

This was originally published in the Herald's June 2018 issue. To read more subscribe to the Herald in print.

The writer is a fine art graduate from the Indus Valley School of Art & Architechture and works with Vasl Artists' Collective.