A visible battle between aggressive development and retreating nature ensues on the road that leads from Islamabad to Murree. As the federal capital and its sprawling suburbs recede in the background, low green shrubs on the roadside hills give way to a thin forest of coniferous trees up against a formidable foe — burgeoning schemes to build houses and markets.

Some of these schemes are owned and managed by corporate giants such as Bahria Town and Sheraton hotels and restaurants. Many others are run by smaller operators who are said to be peddling either forest lands or properties that are disputed between the forest department and private claimants.

Through wall chalkings and billboards, the Punjab forest department has made an obvious effort to showcase its ‘success’ in forest conservation; nurseries run by the department can be seen at regular intervals and younger trees, indeed, are spotted growing at many places where older ones have been cut down.

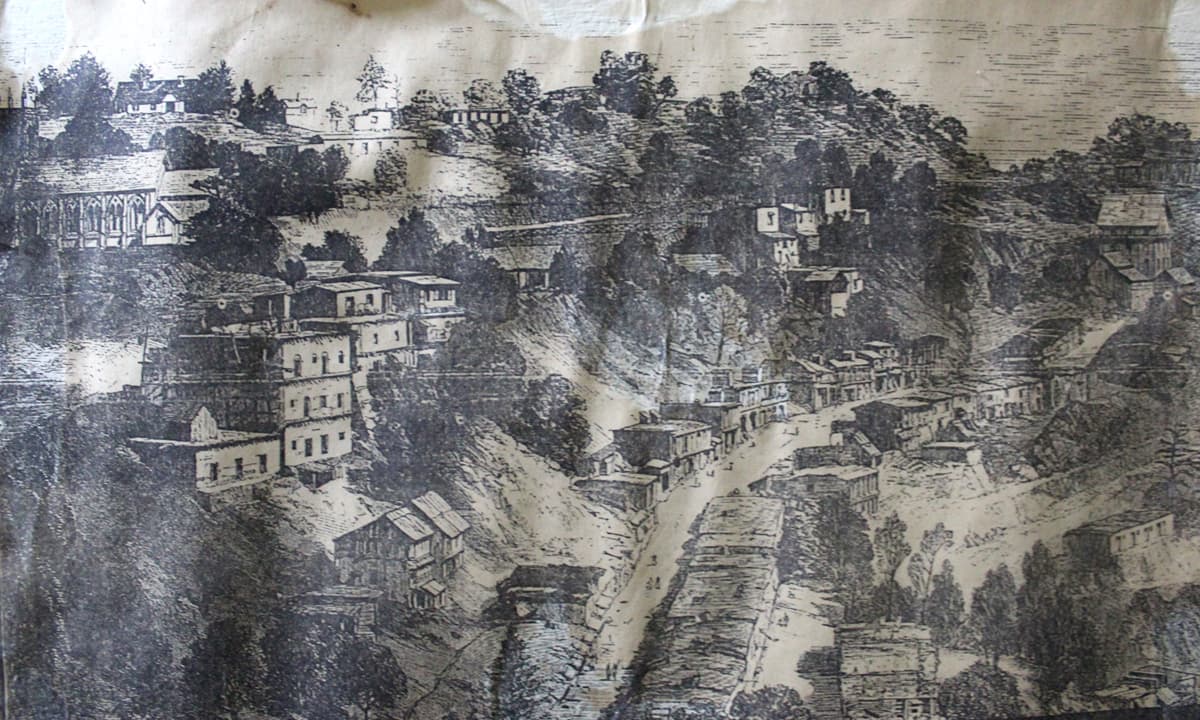

As Murree draws closer, colours shift from green to brown to grey. Seen from the nearby mountaintop of Lower Topa, the hill on which the town is built seems like it will collapse under the weight of the reinforced concrete placed on it.

The entrance to Murree is clogged with piles of burning garbage, open sewage lines and an endless chain of cars and motorcycles, producing noxious fumes and ear-renting noise. This environmental pandemonium takes an alarming turn inside a plot of land opposite a bus stand, where between 150 and 200 pine trees have been chopped down since the middle of 2017 to make room for a 127-bed hospital. Although construction has been halted due to winter, the tract of sloping land looks like a graveyard of trees on a cold November day — the earth is dug up and wooden debris is scattered around. Heavy construction machinery is parked where the felled trees once graced the view.

At least three full-grown pine trees have been chopped down, their timber neatly piled in a corner of the lawn of a rest house owned by the Lahore High Court.

Local responses to the building of the hospital have been mixed — a measure of how civic needs and the natural environment are often pitted against each other in tourist areas like Murree where, paradoxically, human presence and activities are heavily dependent on the preservation of nature. Some local journalists and residents criticise the cutting of trees; others view the medical facility as a necessary substitute to the dilapidated civil hospital on the other side of town. Trees can be replanted, they argue, but a human life once lost is lost forever.

A little further up from the bus stand, The Mall is packed with tourists and vendors even though the inclement weather is hardly conducive to a stroll. Situated on the road’s busiest part is Chinar Hotel, owned by octogenarian Haji Shifaul Haq. He walks into his warm, dingy office behind the hotel’s reception with a walking stick in hand.

Haq sports a curled moustache and is dressed in a warm winter coat with a pocket square and ascot scarf — all remnants of colonial-era fashion. The walls of his office are plastered with old photographs of Murree, newspaper cuttings related to the environment and numerous awards he has received in his role as president of the local horticultural society, a private initiative of concerned citizens established in 1995.

He picks up two hand-painted signboards from behind his desk and holds them up. “Mujhe mat kaatain,” he reads out one of them — “Don’t cut me.” He has nailed numerous such boards to trees along The Mall, recording their species and ages. “There were people in the local administration who used to help me out,” Haq says in a shaky old voice. “Now it’s just me.”

He reminisces about a time when Malika-e-Kohsar or the Queen of the Hills, as Murree is affectionately known, was better protected. Under British rule, he says, forestry laws were severe to the extent that those wearing spiked boots (quite in vogue back then) were not allowed to walk through forests to avoid damaging the saplings and to prevent accidental fires. “Families living around forests were allowed to cut a tree only on two occasions: a death and a wedding.” And they were required to replant the same number of trees they had cut.

In colonial times, Murree and its adjoining areas had all kinds of trees, not only conifers. There were apple orchards and vineyards (one of them owned by Haq’s grandfather in their village nearby) and there were trees of batangi (Himalayan wild pear), he says. The forest was also full of trees that produced the finest and most durable timber — deodar, biyaar (blue pine), chir pine, cypress. “We had some of the rarest and most expensive tree species,” says Haq.

The thriving forest offered people sustenance during the most severe weather conditions. “When there was no fodder for animals in the winter, we would pick seeds and leaves from oak trees and boil them to make animal feed. We would burn pine flowers to keep ourselves warm.”

Many of these trees have disappeared, he says. “Others will eventually follow suit.”

And as the trees have vanished so have the many animals that used to live in Murree’s forests. “There was a species of leopard here,” says Haq. “We called it guldaar because it had spots that looked like flower patterns.” It is nowhere to be seen now. Many species of pheasants are also vanishing, he adds. “If you walk around in the morning, you’ll see fewer migratory birds in the sky.”

The most egregious move to take urban development into the forest was a 2003 plan by the Punjab government to build what it called New Murree, a residential township and tourist resort spread over 4,000 acres of reserved forest land in Patriata just outside Murree. Local residents, environmentalists, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and the media all opposed the plan. They feared the construction would not only damage the forest but would also increase the likelihood of environmental catastrophes such as landslides, earthquakes and depletion of water resources.

Their opposition caught the eyes of the Supreme Court, which took suo motu notice of the plan in 2005.

After judicial proceedings stretched over three years, the government finally scrapped the idea in 2008.

That, however, did not put an end to illegal construction on forest lands. In 2010, Murree’s municipal administration estimated that 17 housing societies were built illegally in and around the town. Lahore High Court Chief Justice Khawaja Muhammad Sharif took suo motu notice of the issue and the Pakistan chapter of the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) became party to the case providing to the court and forest department maps and photographs that showed how housing societies had encroached into the forest.

Under high court orders, the forest department signed an agreement with the WWF for an extensive survey of the housing societies. Subsequently, four teams from the revenue and forest departments carried out a 15-month survey, revealing in January 2013 that 2,862 acres out of 47,744 acres – about six per cent – of land owned by the forest department in Murree tehsil had been encroached upon by land grabbers, illegal builders and timber traders.

The provincial government identified 2,325 encroachers and filed 140 police cases against some of them. Consequently, the forest department managed to retrieve 1,279 acres of its land. The remaining 1,577 acres remain under illegal occupation.

Haq says he is in favour of development as long as it is done in a sustainable manner. “The problem occurs when individuals within the state machinery allow a massacre of trees for their personal benefit.” As an example, he points to the cutting of trees within rest houses owned by various government departments such as those for railways, police and the superior judiciary.

In one of the alleys that branches off Bank Road near Murree’s Kashmir Point lies proof of his claim in plain sight: at least three full-grown pine trees have been chopped down, their timber neatly piled in a corner of the lawn of a rest house owned by the Lahore High Court. The stumps suggest the trees have been cut only recently.

This is not the first or only instance of tree-felling on these premises, says Haq. Earlier in the year, he claims, a few chir pines at the back of the rest house were cut down to expand servant quarters.

The roof of Haq’s hotel serves as a nursery where he grows plants of varying shapes and sizes. He shuttles among the plants with the energy of a young man, stopping occasionally to comment on their various properties. He then steps out onto a sunlit terrace, looking at the depleting green cover. The orange bloom of the occasional autumn tree looks foreign.

To combat deforestation, Haq suggests strengthening forestry laws and their implementation without exception. “Until recently, if you cut down a pine tree – which has at least 400 cubic feet of wood to offer – you could be let off after paying a 500 rupee fine.” This legal laxity, he believes, is a major reason why the timber mafia operates quite actively in and around Murree.

The first place that captures the attention of a commuter travelling from down country to Gilgit-Baltistan is Dasu, the headquarters of Kohistan district in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. It is a delight for nature lovers: a river flows just past the town and high, majestic mountains surround it from all sides.

The place also offers another spectacle: thousands of logs of wood are stockpiled in a highly organised manner on both sides of the Karakoram Highway that passes through Dasu.

These stockpiles are visible not just in this remote outpost of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa but can also be spotted in many places along the Karakoram Highway till it reaches Gilgit-Baltistan’s Diamer district. The logs stored in Harban, a village about 72 kilometres northeast from Dasu, alone offer approximately 200,000 cubic feet of wood, valued at 240 million rupees at the minimum market rate of 1,200 rupees per cubic foot.

The Gilgit-Baltistan region’s topmost civilian officer, Chief Secretary Dr Kazim Niaz, puts the total volume of the timber stored in Diamer at 1.8 million cubic feet. Its total value could easily be more than two billion rupees.

Not long ago, these logs were old, tall conifers.

Many locals do not see any problem with this massive logging. Some are happy they have found jobs in their hometowns as caretakers of the stockpiled timber. One of them, clad in a black leather jacket and a pink sweater, says he earns as much as 20,000 rupees per month only by keeping an eye on the logs lying by the roadside in his village.

Unlike elsewhere in Gilgit-Baltistan, forests in Diamer district are community-owned. Under a provision of the area’s deed of accession to Pakistan, local residents have collective proprietary rights over the forests, though the forest department has the exclusive authority to manage and maintain them. The community can lease, sell and cut trees only by following government procedures.

As a first step in this procedure, at least 60 per cent of the members of a local community must approve before a forest can be sold to a contractor. Then, the deputy commissioner – the highest government officer in the district – approves the sale, changing the status of the forest to ‘leased’. The contractor then approaches the forest department to mark the trees which can be cut. The district forest officer, accompanied by other members of the district administration, subsequently marks the trees, specifying that only dead, damaged and mature ones can be cut (a mature tree’s trunk has a girth of 28 inches).

This procedure has been violated time and again, acknowledges Niaz. “The trees have been cut brutally.”

There had been a complete ban on cutting trees in Diamer’s forests since 1992, but in 2002 the federal government issued what in official terminology is called a “work plan” — essentially, permission to lease and cut forests. The work plan, officials say, had to be suspended in 2003 after it resulted in a massive rush to cut trees, mostly without the mandatory supervision of the forest department. The ban on felling trees was reimposed, though it has not been able to stop illegal logging.

The stockpiles along the Karakoram Highway are the result of all the trees cut between 2002 and 2015. They are still lying in the open because forest trees, felled both legally and illegally, require official permission for their transport outside the Gilgit-Baltistan region. The regional government usually announces a policy for their disposal every now and then. This includes determining the royalty to be paid to forest owners and levying a tax on contractors.

Many such policies have been announced since 2002. The latest one was issued in 2017 and approved by Prime Minister Shahid Khaqan Abbasi in a meeting of the Gilgit-Baltistan Council – a high-level official forum that effectively governs the region – held in Skardu on October 25 last year.

Under this policy, the royalty has been fixed at 100 rupees per cubic foot of timber and government tax at 600 rupees per cubic foot. After a contractor pays the two amounts, all the timber he has cut, legally as well as illegally, gets government approval for sale in markets all over Pakistan, where the lowest going rate for a cubic foot of timber is 1,200 rupees. In the biggest down-country markets, such as in Karachi and Lahore, the rate can be as high as 3,200 rupees per cubic foot. Even after giving forest owners and the government their dues, traders still hope to earn windfall profits from the stockpiled timber.

Officials and local residents, therefore, agree that disposal policies only incentivise the felling of trees. “Whenever we gave a disposal policy, it started a new phase of forest cutting,” says Amjad Hussain, a former member of the Gilgit-Baltistan Council. This vicious cycle will never end “until we put a permanent ban on the transportation of timber, both through smuggling and legal channels”, he says.

Others say disposal policies are announced in spite of their visibly negative impact on forests because many involved in the timber trade are extremely well-connected. Haji Wakeel, a known timber trader from the forest-rich Tangeer valleys of Diamer district, was Gilgit-Baltistan’s minister for forests a few years ago, local residents reveal. Wakeel is deceased but the same post is now held by his brother Imran Wakeel. Some other politicians from the area – such as former health minister Haji Gulber, incumbent minister for excise and taxation Haider Khan and minister for agriculture and livestock Haji Janbaz Khan – are either themselves timber traders or have close relatives involved in the business.

It is the lobbying power of such people that has led to the announcement of the newest disposal policy, sources in the region’s government say. At the meeting where the policy was approved, Chief Secretary Karim Niaz opposed it tooth and nail. He suggested that the stockpiled timber be allowed to go to waste in order to send a message to timber traders that the government would not let them benefit from their illegal activities, sources reveal. Gilgit-Baltistan Chief Minister Hafeez ur Rehman, on the other hand, is said to have argued that the government could earn millions of rupees in revenue by issuing the disposal policy. Niaz then proposed imposing a prohibitively high amount of tax on the stockpiled timber in order to discourage its trade. This suggestion too was not accepted.

Forests in Ghashu Valley and Pahut Nalla areas of Gilgit district are located in extremely high mountainous terrain with no road access. Parri, the nearest town on the Karakoram Highway, is more than 30 kilometres southeast of these forests and the nearest village, Zwar Shing, is more than 10 kilometres south of them. A dilapidated narrow road links Parri with Zwar Shing, but the forests are accessible only on foot.

The logistical difficulties involved in operating within these remote areas are no deterrence to timber traders. They, indeed, have devised a novel way to bypass some of them. They cut trees into logs and throw them into running streams in the months of March, April and May, when the flow of water is quick enough to carry them forward but not too quick to make it impossible to retrieve them. The logs are fished out of the water at a place called Shauj. From there, they are transported to Zwar Shing in jeeps. Their final destination is Gilgit city, where they are sold to traders and individual customers coming from all parts of Gilgit-Baltistan region.

These logs come from government-owned forests that are protected by law from any human intervention unless approved by the authorities. There are at least five checkpoints, manned both by the forest department and police, between the forests and Gilgit city to ensure that no illegally felled trees are transported to the market. Yet almost half of all illegal timber does filter through these checkpoints because there exists a close nexus between timber traders and the forest department, says Muhammad Nazeem, who runs the Wildlife Conservation and Social Development Organization, a non-governmental organisation in Chakarkot village of Sai Bala Union Council. Zwar Shing and the forests are part of the same union council.

The remaining half of the timber – measuring 900,000 cubic feet, according to Niaz – gets stockpiled in the anticipation of a government amnesty scheme to allow its transportation to Gilgit city. Under the latest scheme, announced in October 2017, the regional government said it would buy all the stockpiled timber at 300 rupees per cubic foot. It gave timber traders a month to declare their stocks in order to benefit from the scheme. No one showed up.

They were expecting to get a higher rate of 600 rupees per cubic foot, says Karim Dad Chughtai, assistant commissioner of Jaglot subdivision which includes Sai Bala’s forests. The government did not budge. Instead, it decreased the rate it was offering to 170 rupees per cubic foot. Surprisingly, this worked.

Sensing that the government could either confiscate their timber without paying anything or would never allow it to pass through to Gilgit city, timber traders started transporting their stocks of wood to Parri Bangla in November 2017. The local administration had set up a temporary office there for the purpose of receiving and measuring the timber to auction it later.

In similar government-organised auctions in the past, timber traders would make a cartel in order to keep their bid prices low, says the chief secretary. They also did not allow anyone from outside their own area to take part in the auction, he adds. This time round, he has plans to make the auction as open and fair as he must.

Muhammad Dildar Azizi, a 50-year-old resident of Jaglot town in Gilgit district, remembers his childhood when forests in his native area were abundant and dense. “The forest in Chakarkot was so thick that no one could walk through it,” he says. Over the last three decades, he says, trees have been cut without restraint. “Now one finds logs all around.”

People live about eight kilometres further up into this valley,” he says. The whole area, including his own village, has no gas supply. The nearest place to buy wood is the town of Patikka, about 14 kilometres to the west.

By most accounts, illegal cutting of forests started in the late 1980s but accelerated after 2010 when automatic saw machines were first introduced to local forests. These machines not only cut big trees quickly but also converted them into logs within no time, says Muhammad Nazeem of Chakarkot.

For Niaz, the economic backwardness of Sai Bala and Diamer is the main reason why their residents are involved in timber trading. He cites a survey conducted by the United Nations Children’s Fund (Unicef) titled Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2016-17 that lists Diamer as the most backward district in Gilgit-Baltistan region in terms of the physical, social and economic well-being of its residents. The same is the case with Sai Bala in Gilgit district, he says.

Another related problem is the need for firewood to keep homes warm during the winter months when temperatures in many parts of the region drop below zero degree centigrade. Local residents estimate that a family needs about 80 kilogrammes of wood per day for four winter months — a whopping 9,600 kilogrammes of wood every year.

The government reckons the requirement could be much lower — it provides 40 kilogrammes of wood per day to its officers working in grade 17 and above; those working in lower grades get 20 kilogrammes of wood per day. Yet, even by the lowest estimate, a family requires 2,400 kilogrammes of wood each year, equivalent to at least one grown-up tree.

Forests are the only source of procuring all this wood.

The region’s forest department recently suggested that instead of providing wood to its officials, the government should give them money so they can arrange their own heating mechanisms based on other sources of energy such as gas and electricity. The proposal has yet to become policy.

Any policy formulation, indeed, takes quite long in Gilgit-Baltistan because those who have the power to make, revise and revoke policies sit in Islamabad. Though the region has its own legislative assembly and its own government, most policies have to be approved by the Gilgit-Baltistan Council, which is packed with representatives of the federal government. But once a policy is made, its implementation becomes the sole responsibility of the regional government.

Here is just one example: sometime late last summer, Chief Secretary Niaz sent a proposal to the federal finance division seeking the creation of 270 new government posts for Gilgit-Baltistan. He also sought around 20 jeeps/cars and 50 motorcycles for the region’s officials. “It has met with the usual cold response,” he says.

The lack of close coordination and collaboration between regional authorities and the federal government is especially glaring as far as forests are concerned. The forest management law in Gilgit-Baltistan is archaic and the region’s own legislature does not have the power to change it. Formed in 1927 and last amended in 1991, the law envisages a maximum fine of 3,000 rupees and a jail term not exceeding three months for a person who damages a forest. These are ridiculously lax punishments for cutting a conifer tree that takes on average, at least, 25 years to reach maturity. (This speed of growth is still lightning fast compared to that of juniper trees that are said to grow only half an inch per year and can be found in an old forest in Balochistan’s Ziarat district).

Within this legal framework, says Niaz, Gilgit-Baltistan’s government cannot properly deal with those who are causing the forests irreparable damage. The regional government, therefore, has suggested a number of changes in the law to improve its effectiveness. “We have asked for a separate forest force that must be armed and well-trained. We have asked for increasing the fine and duration of imprisonment. And we have asked for extending the remit of the law to some offences that it does not cover.”

Above all else, Gilgit-Baltistan needs to create a forest management system that has a sufficient workforce and is well-equipped and well-trained to do the job. Forests in Diamer district alone are stretched over 536,436 acres – comprising about 77 per cent of all forest area in Gilgit-Baltistan – but the forest department there has only 103 employees. Many of them are actually administrative staff who do not have anything to do with ground monitoring and management of forests. Moreover, the department has only three jeeps for the whole district and these too are used by its top officials, the district forest officer, the regional forest officer and the conservator. Field staff has only eight motorcycles for patrols.

There is a reason why the Neelum River is called Neelum — or sapphire in English. Its waters grow increasingly blue as a road meanders along them upstream from Muzaffarabad. What, however, is odd for a river passing through these mountains is that its banks are as brown as a brick and as barren as a desert. Every few kilometres, rocks and earth have slid into the river, forcing it to change its course. Such minor environmental destruction is visible at regular intervals along the entire 29-kilometre journey from Muzaffarabad to the village of Panjgiran to the northeast.

A narrow uneven road, squeezed between a steep decline on one side and an almost vertical rock face on the other, leaves Panjgiran and leads into the high mountain valleys in the north. About three kilometres up the road, a dozen people belonging to Tatrial village are sitting outside a grocer’s shop at a table laden with boiled eggs, fried chicken, tea and biscuits, suitable snacks for a cold November day. They are all concerned about a common challenge: how to gather enough firewood to protect their families from the oncoming winter.

One of them, Mir Younas, shields his eyes with one hand to avoid the midday sun and points up in the distance. “People live about eight kilometres further up into this valley,” he says. The whole area, including his own village, has no gas supply. The nearest place to buy wood is the town of Patikka, about 14 kilometres to the west. “How do you want people to cook or keep themselves warm through the winter if not by cutting down trees?”

But felling a tree without official permission attracts a government fine — between 20,000 and 30,000 rupees, according to Mir Mumtaz, an older member of the group with a neatly trimmed white beard.

Until recently, every local family used to cut three chir pine trees in winter, he says, “but we have brought that down to one tree” mostly to avoid official penalties. The only way the government can stop the cutting of trees completely, according to Mumtaz, is to provide an alternative means for indoor heating and cooking.

A massive pile of timber sits outside a house on a slope behind him. Members of the household, including women and children, must have worked some hours each day during the summer to put together the firewood before it was supplemented by trees cut by men in the family.

Tree cover on Tatrial’s mountains still looks thicker than on the banks of the Neelum. Chir pine trees abound on nearby hills. Snow-capped peaks in the distance are wrapped in blue pines, locally known as kail. Its wood is much sought after for use in furniture.

These evergreen conifers stretching both eastwards and westwards are categorised as a species of “least concern” on a list compiled by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), indicating that these are not threatened.

Yet, the rapid decline of pine forests in different parts of northern Pakistan is ringing alarm bells. A 2016 report published by the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa forest department, for instance, says that 75 billion rupees worth of wood is being burnt every year in the province, having become a major factor in the 74 per cent decline in the regeneration capacity of the province’s forests since 2013.

We tried to save as many trees as we could. But increased traffic along this route forced us > to convert this [avenue] into a double road.

The laws that govern forests are a hotchpotch. Forest maintenance has been a provincial responsibility for a long time, but sometimes there is an overlap between the mandate of the federal ministry for climate change and the provincial forest departments — leaving trees in no one’s care. Sometimes provincial laws differ from one district to another. Khyber Pakhtunkhwa’s law, for example, allows the residents of Swat to collect deadwood from the forest floor, but a fallen tree is immediately seized by the government for auction in most parts of the province’s Galiyat region that abuts Murree. Residents of Tatrial are similarly prohibited from retrieving deadwood from forests.

“We have to apply for a permit and participate in an auction if we want to get hold of a fallen tree from government forests,” says Younas. “Cutting down trees growing on privately owned lands also requires permission from both the land revenue department and the forest department.”

Those involved in the illegal timber trade, however, do not bother about these legal niceties. They connive with government officials to cut and transport trees illegally. Forest fires are the most frequent excuse used by timber traders and their governmental collaborators to fell trees. “If truth be told, most forest fires are not accidental,” says Younas. “On nights when arson happens, trees are chopped down and trucked out of the forest with help from forest guards. The remnants are then set ablaze so that not even the stumps of the felled trees are identifiable.”

Forest fires are common almost everywhere in Pakistan. Most recently, in early December 2017, a whopping 700 acres of forest were burnt down over three days in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa’s Shangla district. Two months earlier, a devastating fire hit forests in Upper Dir district of the same province.

Apart from these big blazes, smaller ones seem to be a matter of routine. In May 2016 alone, eight fires broke out in Islamabad’s Margalla Hills reserve forest over the course of just 15 days.

Residents of Kormang village in Shangla district saw an extraordinary scene on the evening of December 7, 2017. Mountain peaks many kilometres down south were all ablaze. “I saw a huge fire spreading very quickly due to strong winds,” one resident recalls two days later.

He says he contacted the forest department and apprised its officials about the fire. He also recalls reports of people living next to the mountain tops that were on fire making efforts to contain the flames before they reached their villages. They removed all dry leaves lying around their houses. They also dug small trenches and filled them with water so that fire could not cross them.

The evening the fire broke out, forest department officials contacted one Hizbur Rahman in Kormang. They wanted him to drive them in his taxi to Utlo village (about 15 kilometres to the south) where mountains covered with dense forests were aglow. Rahman agreed.

But before reaching Utlo, officials concluded the fire was too huge for them to control. “At 2 am, we came back to Kormang,” says Rahman.

They paid another visit to the area three days later on December 10, bringing around 50 people to put out the fire. They succeeded to the extent that they prevented the fire from spreading into human settlements but they could not even go to that side of the mountains where the fire was licking out trees at a brisk pace.

By next day, however, the fire had died down. According to Rahman, it was extinguished by rain that started falling at 4 am on December 11.

Margalla Hills National Park is spread over 31,142 acres of land. Its protected forest serves as an idyllic backdrop for Islamabad besides offering walking and biking tracks and being the origin of multiple natural streams that flow into Rawal Lake, one of the main sources of water for the federal capital. That such an important ecological area must be preserved and managed sustainably goes without saying.

So it came as a shock for residents of Islamabad to hear that 53 illegal stone-crushing plants had been operating from the Margalla Hills for years. Punjab’s Environment Protection Agency made the revelation in a report submitted to the Supreme Court in June 2016.

The court had taken suo motu notice of stone-crushing in May 2016 after coming to know about it through a television news package. The chief justice immediately ordered the federal government as well as the provincial governments of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Punjab to look into the matter. The mines and minerals department of Punjab responded by saying that the crushing plant could exist and function only because the Islamabad Electric Supply Company had provided them electricity connections. Khyber Pakhtunkhwa officials pointed to legal technicalities that barred them from revoking mining leases. The chief commissioner and police chief of Islamabad, however, claimed in front of the court that no mining, crushing or blasting activities were being carried out any longer in the Margalla Hills.

In November of the same year, Justice Mian Saqib Nisar resumed proceedings in the case after a senior lawyer filed a petition about unchecked felling of trees in the national park. The judge reminded officials of a blanket ban not only on tree-cutting but also on any encroachment in the Margalla Hills.

About a year later, on October 15, 2017, Islamabad’s Ataturk Avenue is a scene of massacre of 250 trees — eucalyptuses, jacarandas and chirs. Labourers axe away at the felled trunks, cutting them down to size so they can be thrown in the back of trucks and taken away. Two forest guards watch the noisy traffic go by from a tree trunk they are using as a bench.

“We tried to save as many trees as we could,” one says. “But increased traffic along this route forced us to convert this [avenue] into a double road.”

The avenue passes through the bureaucratic, diplomatic and commercial heart of Islamabad. On one end stand private and public educational institutions, sports facilities, embassies, guest houses and the offices of two major opposition parties. The opposite side of the road is home to many important government offices.

The second guard says, “We will plant twice as many trees here” as have been cut down. “10 times as many,” quickly interrupts his companion.

What will happen if the road needs widening again? Will all the trees they are promising to plant be cut down again? “These expansions are part of the master plan of the city. There is nothing we can do about it,” one says.

Zulfiqar Ahmed, who has worked as a successful food vendor in Namli Maira village of Nathiagali for years, is shocked by the ruthless cutting of trees for the expansion of a local road recently.

Around 150,000 people living in various localities around Ayubia National Park, spread over 8,184 acres of land in Galiyat, are mostly dependent on forests for their firewood needs. The WWF distributed fuel-efficient stoves and solar water heaters to residents in 2016 in an attempt to decrease their dependence on firewood, says Muhammad Waseem, a WWF representative in Galiyat.

This partially addressed one of the many threats forests face in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa’s Hazara area, which includes Galiyat region. Forest wood is also used here to make graves. In the past, people generally used wood from Taxus wallichiana, locally known as barmi, for this purpose, but when it reached the brink of extinction they started using Himalayan cedar. Since Himalayan cedar is also becoming rarer, they are using pine and chir pine lately.

Construction was another sector that used huge amounts of forest wood until recently. The trend of using wood for buildings, however, has been replaced by the use of brick, mortar and reinforced concrete, Waseem says.

All these various uses have led to large-scale deforestation in Galiyat, something that, according to Waseem, is causing landslides and water scarcity. He cites a research study conducted in 2004 that shows that six out of Galiyat’s 23 natural springs have dried up. “This will get worse in the coming years.”

Sardar Saleem, divisional forest officer in Galiyat, acknowledges that forests in Galiyat were under immense pressure but claims his department has successfully checked their decline. Among many other tools and resources, he has at his disposal a 15-member raiding team that takes quick action on any information regarding illegal cutting of trees. Its operations have produced positive results. “During the last six months, only one tree has been illegally cut in Galiyat region as compared to last year when 17 trees were cut,” he says in an interview in November 2017. “But we confiscated all of the 18 trees,” disallowing their illegal trade and transport.

The task of guarding forests can be quite risky though.

Saleem talks about a night in December 2014 when an official of his department received information that two trees had been illegally cut in Kaldaniya Kakul village not very far from Abbottabad city. Saleem left Abbottabad at 11:15 pm with six members of his staff. They parked their vehicles at some distance from the site of the incident so that those who had cut the trees would not run away. As they were walking towards the felled trees, Saleem received a call from his driver who said 15-20 people had attacked him. “They were threatening to set the department vehicles on fire.”

Saleem and his colleagues rushed back but were immediately held hostage. “We managed to send messages to our friends in Abbottabad who sent over police who made our captors flee.”

Rashid Husain, a slim young man sporting a short beard, works as a taxi driver in a village in Galiyat region. A few years ago, he admits, he was a member of the timber mafia — a blanket term for those involved in the illegal cutting of forests and the transportation and trade of logs produced thereby.

Husain narrates a story illustrating how the timber mafia is actively aided and abetted by forest officials.

On a freezing night on December 24, 2012 he and his collaborators were loading illegally cut wood on a jeep to transport it outside a forest in his native Bara Gali area. All of a sudden, he felt a light flash on his face. He immediately pulled out his handgun and pointed it in the direction of the light. As he stepped out of the glare, he realised the man holding the light was a senior forest officer. He wanted to arrest them and confiscate the wood they had cut.

Husain and other members of his group decided to offer the officer some money. “In the beginning, he was uncompromising but soon we succeeded in making a deal with him,” says Husain. They offered to pay him 120,000 rupees and he let them do whatever they wanted with the wood.

Husain also claims to have known other corrupt practices prevalent in the forest management. He alleges how he saw officials “surrender thousands of kanals of forest land to private owners” during mapping done by the Survey of Pakistan, a federal government department, in 2015-16. He was then working as a government contractor (after having quit his work with the timber mafia) and was building pillars to mark the forest boundary in Galiyat. The survey officials shifted the location of the pillars one foot into the forest as compared to where they had been according to a survey done in 1904-05, he claims.

Husain also alleges the forest department granted forest land to 41 people for residential purposes in Galiyat Forest Division during the last few years even though there has been a ban on leasing forest land for any purpose.

Using a public-private model, the forest department provided saplings to private landowners > under an agreement that made the government responsible to take care of the plants.

Sardar Saleem rubbishes these allegations. He says the survey was carried out after the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa government started its Billion Tree Tsunami project. The purpose of the survey, he says, was to determine the original location of the forest boundary as given in the 1904-05 demarcation. Rather than surrendering any forest land, Saleem says, the survey helped the forest department “retrieve 6,660 kanals which the department did not even know belonged to it”. Only 80 kanals of this retrieved land is being contested in courts by its occupants, he says. “The department has taken over all the rest.”

Zulfiqar Ahmed, who has worked as a successful food vendor in Namli Maira village of Nathiagali for years, is shocked by the ruthless cutting of trees for the expansion of a local road recently. He is a staunch supporter of preserving and developing forests for the sake of tourism, if nothing else. “People come here to see nature but if we keep on cutting our forests it will ultimately lead to nothing but an end to tourism,” he says.

Ahmed is happy that the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa government has taken some serious measures to preserve and develop forests. “There is a complete ban now on shepherds taking their cattle herds into forests,” he says. These herds hampered the natural regeneration process of forests by trampling on the saplings and using them as fodder. Additionally, he says, the government is planting 400 million new trees to increase forest cover in the province.

Known as the Billion Tree Tsunami, this plantation drive is a flagship initiative of the provincial administration. Nurseries have been set up across the province in the public as well as private sector to provide saplings for plantation. According to Saleem, public sector nurseries, working under the forest department, have distributed 200 million saplings in different parts of the province free of cost. Another 200 million saplings have been produced by private nurseries and given away for replantation.

The added trees will increase the size and density of forests, according to Saleem. Usually, he says, “the forest department sows around 430 plants in an acre of land but 500 to 1,200 plants per acre have been planted in Galiyat under the Billion Tree Tsunami.”

New trees are also being planted on privately owned lands in order to increase the area that comes under ‘forests’. In Galiyat, Saleem says, “We have done plantation at 51 private sites.” The provincial government is giving local communities money to engage watchmen to keep an eye on these private forests.

At a conference in the German town of Bonn on September 2, 2011, IUCN set a goal to restore 370 million acres of the world’s lost forests by 2020. This target became known as the Bonn Challenge and received global endorsement in 2014 after the United Nations Climate Change Summit adopted it. Pakistan was among the signatories to the initiative.

Back home, the government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa headed by the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) took a lead in implementing the Bonn Challenge, pledging to bring about 860,915 acres of additional land under forests by 2020 besides preserving and developing existing forests. Plans were drawn up, funds allotted, official teams put together and the forest department mobilised to accomplish the task.

The man leading the project, Malik Amin Aslam Khan, orders a cappuccino in the lobby of a five-star hotel in Islamabad on a December evening in 2017. Fresh from chairing a conference on climate change the same day, he shakes hands with a few eager students before settling down into an armchair.

A PTI member, he is not new to mixing environmentalism with politics. He was elected a member of the National Assembly from his home constituency of Attock in 2002 and served as state minister for environment in Pervez Musharraf’s government. Although no longer a legislator, he has come into the spotlight in recent times as a leader of the task force that spearheads the Billion Tree Tsunami.

“We already had a green agenda before 2013 but after the elections we had to tailor it specifically to Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. This meant refocusing on forestry since it is not only the main environmental concern for the province but also a major source of income and employment,” he says.

One of his early tasks was to come up with realistic targets after consultations with the provincial government. They ultimately settled on a two per cent increase in the overall forest cover of the province over the next five years. “This came down to slightly less than a billion trees but we decided to aim [for a billion trees] because it sounds more impressive,” he says, laughing. “It was a daunting challenge and also a tough political sell since not many [voters] are bothered about the environment.”

The task force also decided that it would achieve 60 per cent of its intended target by helping dead or dying forests regenerate themselves naturally, estimating that this would help about 1,000 trees regrow in a single acre of forest land every year. To his surprise, he saw that about 1,400 trees regrew in each acre in the first year. This rose to 2,400 trees annually per acre by the time the billion tree target had been achieved in early 2018, he says.

The remaining 40 per cent of the target was realised through the plantation of new forests. Using a public-private model, the forest department provided saplings to private landowners under an agreement that made the government responsible to take care of the plants during the first three years of their life. The agreement also allowed growers to harvest trees every five years — but not without planting new ones.

The project officials also took great care in selecting different tree species for different areas. “We ensured that eucalyptus was planted only in waterlogged regions, particularly in the southern districts such as Bannu, Dera Ismail Khan and Tank,” says Aslam, who is also an IUCN regional councillor for Asia. “It was remarkable to see vegetation return to these areas once the water table went down. All of a sudden, foxes and rabbits came back to their habitat.”

The project has been largely hailed as a success by most local and international observers. That, however, has not helped quell all criticism. A question that continues to nag PTI and the provincial government is about the very title of the project: how does one go about proving that a billion trees have actually been planted?

“I agree that monitoring can be a major issue in such a vast project,” Aslam responds. “That is why the [project] is being publicly tracked by not only the forest department and the provincial strategic projects department but also the federal auditor general’s office.”

In order to ensure further transparency, he says, the provincial government approached one of the most credible environmental agencies in the world: the WWF. “They used GIS [Geographic Information Systems], along with random sampling, in 28 forest divisions of their choosing and observed the progress there year by year.”

The 14-page national forest policy is meant to provide a basic framework for tackling – but first acknowledging – the grave threats posed by deforestation and climate change to the whole country.

A WWF audit report cites an 83 per cent survival rate for the new plantation — a monumental increase over the forest department’s usual average of 33 per cent.

The project has earned Khyber Pakhtunkhwa another distinction: the province achieved its Bonn Challenge in three years by planting forests over 864,868 acres of land. Under its original pledge, the task was to be completed in five years. “It was a huge achievement for us,” says Aslam.

The pride is not universally shared though, even among those who have been a part of the project.

Timber trader-turned-government-contractor Rashid Hussain also took part in the project to grow plants in his nursery in Namli Maira village of Bara Gali, but he complains the government neither paid him all the money it owed him nor removed plants from his nursery on time. (His claims could not be verified independently.)

He says he sowed 100,000 keekar (acacia) plants and received 25,000 rupees from the government soon afterwards, in accordance with the project’s provisions. He cites an official survey to claim that 95 per cent of the seeds he had sowed grew into plants but then the government delayed the removal of the plants from his nursery so much that many of them started dying. “If the keekar plant is not removed from the nursery within six to eight months after sowing, it goes dry and spreads its roots to nearby plants. This makes it useless for replanting,” he says.

The regeneration capacity of his plants had diminished to about just 50 per cent by the time the government teams came to buy the saplings from him. He ended up getting paid for only half of the plants he had sowed, through no fault of his own, he claims.

With one eye on the praise the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa government has garnered over the Billion Tree Tsunami, Punjab Chief Minister Shehbaz Sharif set up the South Punjab Forest Company in 2015 to encourage commercial forestry.

“We took government property which had been declared as wasteland and was either barren for 70 years or was encroached upon, and handed it over to private entrepreneurs for rotational tree plantation and harvesting,” says Tahir Rasheed, the company’s chief executive officer in an interview at his office in Lahore. “Investors spend their own money on planting trees and the government gets a 30-40 per cent share of the profits [after their timber is sold],” he explains the project.

Rasheed, who has previously worked with the WWF in Balochistan, says his company is in the process of handing over 99,077 acres of land in Bahawalpur, Rahim Yar Khan, Dera Ghazi Khan, Muzaffargarh and Rajanpur district to private foresters. The project, he says, will meet local timber needs, reducing reliance on both imported wood products as well as on cutting of forests in the northern regions of the country. “We first need to safeguard northern Pakistan because that is where water regulation for the country takes place,” he says, stroking his long, grey beard. “If there is too much water, or not enough of it, that directly creates not only natural calamities like floods and droughts but also impacts food and water security.”

Rasheed points out that the biggest markets for timber are in major cities in Punjab and in Karachi but the residents have yet to develop a sensitivity towards environmental issues. They view the problem of deforestation as specific to the northern areas without realising that it could well be “the undoing of us all”.

His analysis is supported by the fact that Pakistan never had a national-level forestry policy until 2015. Forests have been a provincial matter since 1947, allowing provincial governments to come up with their own laws and regulations without having to consult and coordinate with each other. This has not just resulted in a confusing mixture of forestry laws operating in different parts of the country, but has also encouraged the trade and transportation, in Punjab and Sindh, of timber cut illegally in the north.

Wohlleben talks of how forests are “superorganisms with interconnections much like ant colonies”, pumping sugar to dead stumps to keep them alive for centuries after they have been chopped.

The 14-page national forest policy is meant to provide a basic framework for tackling – but first acknowledging – the grave threats posed by deforestation and climate change to the whole country. It also sets minimum benchmarks for sustainable forestry that all provinces must adhere to. It stresses the need for renewable energy resources as alternatives to firewood in areas that have no access to gas; it highlights the importance of demarcating timber trade routes to reduce the chances of illegal smuggling; it envisions the creation of ecological corridors to protect biodiversity hotspots; and it calls for reaching out to the youth to spread awareness regarding forestry.

The Council of Common Interests, the highest institution to make policy decisions involving the federal government as well as the four provincial governments, endorsed the policy in December 2016. As of February 2018, there is hardly any evidence that it is being implemented anywhere in the country.

[“J]ust like humans, trees grow and die,” says the bespectacled Dr Pervaiz Amir, a member of the board of directors of Pakistan Water Partnership, a local affiliate of an international NGO, Global Water Partnership, in his office in Islamabad. “Harvesting mature trees is a science and needs to be treated as such,” he says.

A country, for instance, can hope to have a sustainable balance between preserving and harvesting its forests only after it has attained a forest cover comprising 25 per cent to 33 per cent of its landmass, explains Amir. By most generous estimates, Pakistan has a forest cover of just 4.8 per cent, and that too is decreasing rapidly. A United Nations report – backed by most independent observers – claimed in 2010 that Pakistan’s forest cover could be as low as merely two per cent of the country’s total land area.

The same report said the forest area in Pakistan decreased by 33 per cent between 1991 and 2010 whereas the reduction of global forest cover in the same period has been just 0.8 per cent. China and India, on the other hand, increased their forests by 22 per cent and 23 per cent respectively over the same two decades.

But in order to show that there has been no change in Pakistan’s forest cover, the government has been playing number games. “The official trick is to quote the area that has been allotted to protected forests – which is unchanged – instead of the tree cover on that land,” says Amir, who has also served as a member of the Prime Minister’s Task Force On Climate Change.

He warns of such climate change phenomena as rising temperatures, increased frequency of flash floods, landslides, desertification and a consequent drop in the availability of water if deforestation continues in the country as it is.

A 2017 Asian Development Bank report endorses his views. It shows that Pakistan’s annual mean temperature could rise by as much as five degrees and sea levels near the country could increase by 60 centimetres at the end of this century. These changes may lead to a drop in agriculture yield and livestock population besides resulting in many deaths due to heat waves.

To counter this impending gloom, Amir advocates social forestry – widely practised in India – as the way forward. Rather than explaining to people that increasing forest cover will decrease the rate of climate change, he says, “You need to give them direct short-term benefits like a share in the tree’s stump value when it is finally felled after reaching a certain age.” Once local communities living in forest areas get that right, “just watch how they get together to protect trees”.

On its own, a tree cannot establish a consistent local climate, says Wohlleben, since it is at > the mercy of wind and weather.

Amir also argues there cannot be a real change in the present situation unless an afforestation process is built at the union council level and is institutionalised on a permanent basis. “It needs to be inculcated at the school level and students should be made to regularly go out on plantation drives.”

He swears by his experience that the afforestation targets the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa government has set for itself cannot be achieved by a single project alone. It will take a lot more time, money, continuity and community involvement to take effect, he says. “It is not about how many billions of trees you have planted — if you have verifiably planted them at all. It is about making sure that those trees survive.”

If a tree falls in a forest and nobody hears it, does it really make a sound? This human-centric view of unnoticed existence has confounded philosophers for centuries, but German forester Peter Wohlleben has turned the question on its head in his book The Hidden Life of Trees.

He painstakingly draws the picture of a bewildering world where trees are protagonists, freed from the burden of existing to serve human beings. He speaks of electric signals that pass through their roots at the rate of one third of an inch per minute — playing vital roles such as releasing toxic chemicals to fend off predators hungry for leaves or giving off a scent to warn neighbours.

Wohlleben talks of how forests are “superorganisms with interconnections much like ant colonies”, pumping sugar to dead stumps to keep them alive for centuries after they have been chopped. To think of trees as responsive beings instead of lumber, however, may defy some firmly entrenched perspectives: to be considered creatures that can communicate, feel, learn, count and heal instead of existing as an inanimate source of firewood or construction material.

But on its own, a tree cannot establish a consistent local climate, says Wohlleben, since it is at the mercy of wind and weather. “But together, many trees create an ecosystem that moderates extremes of heat and cold, stores a great deal of water, and generates a great deal of humidity. And in this protected environment, trees can live to be very old. To get to this point, the community must remain intact no matter what.”

Promoting this kind of long-term interconnectedness between humans and trees is probably the only way we can win the battle against climate change.

This was originally published in Herald's March 2018 issue under the headline 'The root problem'. To read more, subscribe to the Herald in print.

The writers are members of the staff.