Burdened by poverty, ignorance, the bondage of a repressive system and now, the aggressive onslaught of born-again fundamentalism, the Pakistani woman bears a heavy cross. What hope does she have of breathing through to a new order?

In the year [1985] which marks the end of the International Decade for Women, we look at the many facets of the Pakistani woman, and examine the forces shaping her destiny.

This special story from the Herald's 1985 archives was compiled from reports and material by I A Rehman, Zubeida Mustafa, Najma Babar, Salim Shahid, Sairah Irshaad, Lalarukh Hussain, Najma Sadeque and Talat Aslam.

Thirty years ago no ideological arguments were needed to identify the evils that oppressed women or to contend that religion stood in the way of their eradication.

The position today is that Muslim women (and their allies among men) have to argue all over again that they are entitled to equality, while a resuscitated orthodoxy has been emboldened to deny the rights of women that had been accepted after hundred years of Muslim society's march towards reform and liberalisation. It is not by accident that the very first page of the report of the Commission on the Status of Women, attempts to acquit the woman of the charge of pushing Adam out of Paradise!

"Other faiths have held Eve responsible for the fall, by falling prey to the temptation of Satan, which made her eat the forbidden fruit, and then in turn tempting Adam. In the Holy Quran she is absolved of the offence of being first tempted by Satan and in turn tempting Adam which resulted in the fall of man from the state of bliss and innocence ... In the following verses of the Holy Quran, the words used are "they" "them", "their", and "both". Thus equal responsibility and blame devolves on both man and woman."

Obviously, it has now become necessary to answer people like Dr Isar Ahmad who hold women responsible for all the evil in the world and have not forgiven her for the "original sin."

Whereas in other societies women are engaged in wiping out discriminatory laws, customs and prejudices inherited from previous stages of social development, and which are incompatible with the existing social order in these societies, Pakistani women have been caught in a wave of social regression.

A hundred years ago, the road to emancipation of Muslim women in the subcontinent seemed to have been opened. Politically, emasculated and economically straitened, the subcontinent's Muslims had been forced to examine the causes of their social backwardness — and to accept certain conclusions. One of these was the realisation that at least part of their misfortunes had been invited by their oppression of women.

By treating women as an item of booty in tribal wars long after tribal wars had ceased, and by applying to them the customs of their tribal ancestors or those borrowed from the followers of Manu's anti-woman philosophy, they had promoted social evils which had rendered them incapable of facing the challenge of the times. The result was an acceptance of the need to reform Muslim society by eradicating such evils as polygamy, child marriages, seclusion, oppressive customs related to child birth and marriage, rituals associated with death and burial, and by promoting the education of women.

Whereas in other societies women are engaged in wiping out discriminatory laws, customs and prejudices inherited from previous stages of social development, and which are incompatible with the existing social order in these societies, Pakistani women have been caught in a wave of social regression

This process of purification of the Muslim society through a reinterpretation of the Islamic code must not be unduly credited to the British; it had started long before they swept through the sub-continent. However, the end of isolation from the European communities brought an external factor also into play.

In order to prove the Muslim people's entitlement to progress as equal members of the contemporary world community, forward-looking Muslim scholars had to argue that not only did their faith and their traditions not stand in the way of progress, they in fact enjoined them to acquire an order based on respect for scientific truth and human values.

Also, they had to assert that far from being opposed to the emancipation of women they had a tradition of pioneering female uplift much before the rest of world. It was in this context that Amin Ali could say that the Prophet of Islam had placed women "on a footing of perfect equality with men" in the exercise of all legal powers and functions.

True, the process of reform took time to take off and it proceeded in stages but progress it did, and one by one the obstacles raised to the onward march of Muslim women by the religious orthodoxy and defenders of the feudal order began to be removed. The Muslim woman’s right to education, to inherit property, to protection from child marriage and marriage without consent, to participation in political activity with the right to vote and seek political office came to be recognised and written into law.

The gradualness of the process can be gauged from special references to women's participation, during the battle for the creation of Pakistan Muslim League conventions: first in purdah, then without it and then out into the streets. By the time Pakistan came into being it had been accepted that women would have full political, social, economic, legal, and cultural rights. In principle these rights had been conceded; the task was to accelerate the pace of enforcing them.

According to a booklet written by Maulana jafar Shah Phulwari, and published by the Institute of Islamic Culture in 1955, Islam gave a woman unlimited rights. She had the right to choose a husband for herself and to reject the choice of her guardian; there was no question of any compulsion from elders. The bridegroom had to pay mehr before or after the nikah. He would be responsible for meeting all the needs of his wife, including food, clothing, ornaments (singhar), medical treatment and other household expenses.

True, the process of reform took time to take off and it proceeded in stages but progress it did, and one by one the obstacles raised to the onward march of Muslim women by the religious orthodoxy and defenders of the feudal order began to be removed

No woman could be forced to cook and wash (except where such chores are part of a society's customs). The husband would bear all the expenses of the children and a woman who did not want to breastfeed her babies would not be forced to do so. If a wife demanded compensation for suckling the babies the husband was obliged to pay. If a woman wished to separate from her husband on grounds of dislike, she could secure a divorce.

A woman could have her own legitimate sources of earning and her earnings would belong to her. She was entitled to a share in the property left by her husband, parents, children, brothers and sisters. Lastly, a woman could lay down any appropriate conditions at the time of the wedding which had to be honoured by the bridegroom.

After defining the woman's rights, the sphere of family affairs, the author concluded that in other respects also “woman and man are equal and have identical rights.

An ideal situation, obviously, but the author, in his lifetime saw a violation of all these rights given to women by Islam. Women were abused, sold, denied their inheritance, denied maintenance - in short treated Iike chattel. The situation is grim – and pretty much the same in all four provinces of the country.

Salt of the Earth

The Punjabi woman, particularly in the rural areas, remains in the grip of a feudal code which has gained considerable strength from the rise of obscurantist forces.

In this code, woman is the symbol of honour — man's honour. The feudal guards his honour by confining his womenfolk in strict purdah and prevents his tenants from acquiring a sense of dignity by treating their women as maids or playthings.

The feudal concept of honour has, unfortunately, been adopted by smaller members of the landed aristocracy, too. Women are abducted, assaulted and enslaved to disgrace rivals. In each case, it is man who is believed to be dishonoured; the trauma and the humiliation suffered by the woman is irrelevant. This explains incidents like Nawabpur and similar less-publicised outrages.

The second important feature of the feudal code that affects women is the obsession with land ownership. A feudal may give his daughter a fat dowry and other gifts to deprive her of her share in the land. The desire to keep landed property within the family often results in polygamy, forced marriages of widows, and incompatible matching of young boys and girls. Girls of large feudal families who inherit big estates face severe hardships and even danger. A few women have been killed and several declared insane.

But for all their faults, the feudals have not tried to impose their social norms on the less-privileged rural community except in the matter of restricting education. In several parts of the Punjab, like Dera Ghazi Khan, Jhang, Mianwali and Multan, powerful feudals resist the spread of female education. Confesses a big landlord: "If these ordinary girls get educated, who will work in our fields and who will sweep our havelis and cook and wash for us?" In other matters the feudals leave the poorer women free to step out of seclusion and labour in the fields.

It is the semi-rural, semi-urban community, a relatively new result of the urban encroachment on the rural land- scape, that is imposing new curbs on women. While the agricultural community in the Punjab had certain traditions of female freedom the women did not observe purdah, worked in the fields, could attend melas, and were allowed some say in matters of heart and hearth. The emergence of petty bourgeoise elements in the countryside has led to the adoption of a conservative attitude towards women, and they are under heavier social constraints than before.

The Punjabi rural woman can still be enticed into elopement with jewellery and new clothes after a harvest. Older women are not unaware of their plight or the need to change the life of their daughters. In most cases, when young girls come into conflict with their male guardians over a wish to acquire education or take up jobs, they are supported by their mothers and grandmothers. "We have suffered in silence; we do not want our children to meet the same fate," an old woman in Sihala (near Rawalpindi) recently told a survey team.

The second important feature of the feudal code that affects women is the obsession with land ownership

With all their desire for emancipation, rural women have little opportunity to enjoy an emancipated life unless they migrate to the cities; there are not enough jobs in the countryside and no opportunities for social freedom.

A young schoolteacher in Multan, who used to spend 80 percent of her salary on tonga fare to and from the village 'school she was employed at, told a journalist, "I have accepted this unrewarding job because no one else is available here and I want to be myself."

The most intense feeling of deprivation on this score is visible in the barani areas where men go to work in nearby towns and women yearn to do the same. One of the important social problems in the Potohar region is the large number of girls who studied to become teachers but did not succeed for want of openings.

Thus, while most rural women yearn to move to the cities the problems of even those who manage to do so do not end. Families back home insist on their observing the traditional code even while living and working in Lahore. It is not uncommon to come across a college teacher or a lady doctor who leads a normal life in Lahore but who locks her car in the city and takes out her burqa whenever she goes to visit the family in the countryside.

As regards work conditions, the woman of urban Punjab has the same problems as those in other parts of the country. In the rural areas, the woman’s work schedule has not changed for decades: of tending to animals in the morning, cooking, preparing dung cakes for fuel, washing, then - only thing to brighten, up her life - exchanging a word of scandal across the low house wall.

Daughters of the Desert

Meanwhile in rural Sindh .... A festive eerie atmosphere; incense fills the room. A bride in her wedding finery ... but there's no groom. A bearded mullah asks the father of the bride whether he gives up his right to marry his daughter to any man. The father nods thrice. The poor, weeping bride is then asked whether she gives her consent (not that it matters). She is made to pledge that she will never look at any man except her father and brothers for the rest of her life — and then married to the Holy Book.

Not a scene from a soppy Muslim social film. This is a real life ceremony haq bakhsha, still practised in the rural areas of Sindh to prevent property from going outside the family. It is used when there is no male within the family, to prevent a girl from marrying outside the clan and taking her share of the property away.

In rural Sindh, a woman is not a human being in her own right but a commodity, a piece of property. The hari woman does not enjoy even that status. She is treated like an animal, or a domesticated pet. She cooks, cleans, tends livestock, fetches water from wells or canals often miles away from the house, fetches firewood for fuel and tills and harvests the fields - all work unacknowledged in the ledgers of statisticians.

Age-old codes of honour and morality are additional weapons that can be used by males to suppress or eliminate the Sindhi woman. A woman, married or otherwise, found having an affair with a man, is immediately branded a kari (an immoral woman) and has to die for her sins. The subject of her affections, the kara must die too. A man from the girl's family does the errant couple to death and then gives himself up. But he gets off with a brief prison term at most because a murder committed on the pretext of ghairat is legally considered ‘murder by provocation’.

This loophole in the law allows for the murders of many innocent girls in the name of karo kari. When a man has killed an enemy and wants to escape the death penalty he declares that the dead man was a kara and then looks for a suitable girl in his family whom he can declare a kari and kill.

Sometimes an innocent girl is killed by her father, brother or cousin to get at an enemy. She is declared a kari and the enemy as the kara is named and fined by the village panchayat. The victim threatens to retaliate in kind – and another woman's fate hangs in the balance. Several such incidents have recently taken place in interior Sindh.

Innocent girls also fall victim to the tradition of khoon beha (compensation for taking life). If, in a brawl between two warring families, a man is killed or seriously wounded, the offending party buys escape from prosecution, by offering as compensation a girl in marriage to anyone in the victim's household. After the marriage, the girl’s family severs all connections with her.

These are not the only instances in which girls are abandoned by their families. Prisons in Sindh are overflowing with girls who have been declared karis but have somehow escaped death. They are in jail on zina or abduction charges. The girl's family cannot visit her or else, according to custom, they will be killed for being in league with the girl.

Girls with mental illnesses face abandonment of a different kind. They are said to be possessed by jinns, and taken on long tortuous journeys to pirs and mazars. One of these mazars is Begam Jee near Sukkur, where women are chained for life in what resemble prison cells. There is no concept of psychiatric help.

For that matter, there is no concept of maternity care either in rural Sindh. A pregnant woman is left at the mercy of a village elder. The maximum number of female deaths results from complications in childbirth.

A Women's Division study shows that 22.2 percent females in rural Sindh suffer from tuberculosis, anaemia, malaria and chest diseases. There are no government hospitals near the smaller settlements, and very few LHV’s dais to cater to the needs of rural women.

A majority of the women in rural Sindh are not just bound by crippling traditions but handicapped by a lack of facilities. What compounds their misery is their lack of education.

The female literacy level in Sindh is one of the lowest in Pakistan. According to the Women's Division study, the female enrolment in primary schools is 4 percent; it comes down to 1.3 percent at high school level. Out of 1,847 rural settlements having population of 500 to 1,000 covered by the research, 1,666 settlements did not even have primary education facility for females. Out of 636 settlements having a population of 1,000 and above, there were only 137 settlements which had, female primary schools and only 15 middle schools and two secondary schools. The total female literacy rate in rural Sindh is around 5.2 percent.

Of Tribal Bondage

The plight of the Baloch woman seems little better than that of her Sindhi counterpart. The rigid norms and traditions of the Baloch tribes have changed precious little.

The woman of the Baloch and Brahui tribes on the southern coastal, the central north-eastern and the central north-western areas, is a complete slave to tribal custom and tradition. She can barely breathe without a man's permission. In matters of marriage, she has no say whatsoever, and money is the basis of all marriages.

The Baloch tribal woman bears the entire burden of family and tribal life. Like her counterpart in the Punjab and Sindh she does all the domestic chores: fetching water from far-off springs, collecting wood for fuel, grinding the grain for domestic use on hand-operated grind stones, and grazing the cattle. Apart from this, she also spins cotton and woollen cloth on hand looms, does embroidery and spinning wool for shawls.

Gypsy women even perform the hard duty of pitching tents and folding and carrying them on journeys with their tribe. With changing times, social values have changed somewhat in towns and big cities. In some families, girls are being given an education but there is no breaking away from tradition.

The Pashtun tribes who inhabit the north, north-east and north-western areas of the province have done away with the sardari system but they have their own rigid traditions, which affect women the most. Apart from Quetta and some other big cities where there have been visible changes the Pashtun woman has no status in society. In the interior, all marriages are arranged on the basis of walwar: the man pays a price for a wife and once he has done that, she is his property to do with as he pleases.

There have been horrific instances of wife abuse and the girl's family has not been allowed to intervene. Because young girls fetch a higher price than older ones, child marriages have been frequent, usually immediately after puberty.

Old men wanting young brides have to pay hefty sums. Widows are worth only half of what virgins will fetch. There is also a custom, less widely practiced now, that a brother who does not wish to marry his brother's widow himself can dispose of her in marriage to someone else for an appropriate walwar.

The Pashtun woman does more or less the same work as the Baloch man, but since this area has a lot of water and fertile lands, there is a lot of agricultural activity. Apart from their domestic chores, the Pashtun women, also help their men in the fields and orchards. They are expected to tend the cattle and assist in cultivation. Polygamy is widely practised among well-to-do Pashtun men. There is no concept of family planning and the Pashtun women have to bear the load of frequent childbirth.

In the cities, the Pashtuns are more open to modern education, therefore in the universities and colleges there are more Pashtun girls than Brahui or Baloch girls. Some of them have also entered politics. But in spite of this, when the question of active participation in practical life arises, these women are severely hampered by tradition. Ultimately the Pashtun woman has to return to domesticity. Even if they are qualified, very few are allowed to pursue careers in medicine, teaching or other fields.

The development that has taken place in Balochistan has hardly affected the Baloch woman. There has been an increase in girl's schools in the rural areas, but there is a scarcity of female teaching staff. Nor do the rural health centres and basic health units have an adequate number of nurses and female doctors.

Statistically women constitute 43 percent of the 52 lakh population of Balochistan. But there is only one girls degree college in Quetta. Three intermediate colleges were established in Loralai, Sibi and Kalat, but the Kalat college closed down because there were no admissions.

The college at Sibi is functional because it is coeducational. The Loralai college is also running, because of the new generation of Pashtun girls who are being allowed the benefits of education. The percentage of female literacy in the province however, is a bare two percent.

Legally, the Baloch woman has barely any rights. With very few exceptions she has no right to own property, nor even to the presents given her on her marriage. If divorced, she is entitled to nothing but the clothes on her back. If widowed, she receives a bare subsistence allowance from her husband's estate. In a Baloch house-hold, women are regarded as mere assets in the division of its property.

Honour Bound

Lounging outdoors on a charpoy, a Khan was holding forth on the subject of women. He spoke passionately (and approvingly) of the universal purdah in the area. When someone pointed out a number of women working in the fields in the distance, he seemed taken aback. "Oh, those women," he said in a disparaging tone. "They are just ordinary poor women. Nobodies really. To segregate one's woman is a question of honour. Why should those without any honour to lose bother about such things?"

This stark statement is the crux of the matter.

In the Frontier, rural women have always worked in the fields. The myth that women in these areas are hidden from public view only holds for women from a socially superior strata.

Pakhtunwali, or the Pakhtun code of behaviour, lays great stress on female segregation. Women are segregated to prevent them from being in a position where they could dishonour a man. Pakhtunwali, however, represents a sort of aristocratic ideal rather than an approximation of what actually exists.

Women in the Frontier, though admittedly in a grossly disadvantageous position vis-a-vis men, are not simply passive, stoical upholders of the burden of oppressive traditions. Many women do, in fact, wield a great deal of influence behind the scenes.

Many women have invested the money their husbands send from the Gulf, in Suzuki pickups and small minibuses and have become entrepreneurs. Of course, they play their role behind the scenes, but many are reported to have become experts in financial dealings.

But there is one field where they have not yet been able to break what constitutes Pashtun tradition. To a man, land represents honour and no woman is allowed to inherit it. Many men acknowledge this practice to be un-Islamic but they will not tamper with tradition.

But now a new element is changing the face of tradition. The massive migration of men from the rural areas to the Gulf states has left several villages in the province populated by women, older men and children. Women have been forced to take responsibility for the land and livestock, and for the hundreds of tasks, big and small, that were traditionally the domain of men. One interesting factor is, the way in which remittances from the men in the Gulf have been utilised.

Many women have invested in Suzuki pickups and small minibuses and have become entrepreneurs. Of course, they play their role behind the scenes, but many are reported to have become experts in financial dealings. A quiet revolution may well be in the making without our being aware of it.

This recent development in the Frontier has given women a certain measure of independence but this independence should not be mistaken for licentiousness. In the Frontier, the penalty for even an innocent liaison with a man is death.

The Killing Fields

Fida Ali, a Balti, and long-time chowkidar at a resort in Kachura, one of Pakistan's northern areas, submitted his resignation to the management. His grounds for leaving: "my daughters. Now that they're old enough to support me, I can retire gracefully." Prematurely too, for Fida Ali is barely 40. But like most of his male counterparts in that part of the country, and unlike most others in other parts of it, Fida believes that "girls are God's gift to fathers."

The sentiment is not surprising, for in Baltistan, which comprises areas like Skardu, Gilgit and Hunza, Women constitute a major part of the work- force — and it is labour which comes free.

Superficially, rural Baltistan seems light years away from the rest of the country. Apart from the obvious topographic, climatic and cultural differences, socially too there seems to be a vast chasm between the marked conservatism of the urban centres and the apparent liberalism of these areas. Here women are an active presence, seen and heard.

Traditionally, there has been little or no chaddar and chardiwari; here women's movements are less constricted. But this liberalism is a facade: it doesn't come easy, and doesn't go far.

The society remains patriarchal and the men make the rules. In Skardu and its surrounding areas, while men by and large take it easy, women are out in the fields — sowing, cutting and ploughing (in certain areas they are even used in place of bullocks) on the often treacherous mountainsides, tending to their flock by the riversides, panning for gold, and of course in their traditional place — by the hearth, tending to their homes, their children and their men. It is hard labour, made harder by the natural elements. So hunched backs, stooping shoulders and premature aging are common.

Isolated as this area is from outside influences, chauvinism nonetheless seems to have found its way here. For while the men feel free to delegate all responsibility to their women, they accord them none of the accompanying privileges. Child marriages are common and once married, the girls transfer their loyalties and their labour to their new families.

New influences which have permeated this area have also had a regressive effect on the status of women. Never fanatically religious, these people (traditionally Shias) have now come under the fold of Khomeini's fire and brimstone fundamentalism.

Posters of the 'Imam' are plastered on every wall, and Balti mullahs financed by the locals are sent to Iran every year for fresh indoctrination. The results are becoming obvious: a once relatively laid-back social order is giving way to a much more rigid system, and women are bearing the brunt of it.

The Gilgit area, more urban and affluent in character, is obviously more conventional than its neighbouring regions. Women, especially those of the upper classes, are largely confined to their homes. A few are educated but rarely beyond the elementary level. This is a predominantly male-oriented set-up and procreation is regarded as a woman's prime function. A barren woman is considered to have an 'evil eye' and is consequently of no use.

In Hunza, the rural woman's lot remains basically the same as her Balti counterpart's, but in more affluent circles, Hunza women remain behind closed doors.

New influences which have permeated this area have also had a regressive effect on the status of women.

However, they manage to wield authority from behind closed doors. This may be due to the fact that Hunza is almost a hundred percent Ismaili: a spirit of community welfare and a relatively relaxed attitude towards women marks this sect.

Affluence also determines the lifestyles of Chitrali women. In the upper classes women spend their days sewing, embroidering, gossiping, visiting female relatives and attending their children. In the lower classes women do more menial labour, but mainly within their homes since women of all strata are largely confined indoors.

Traditionally, during their menstrual periods and for forty days after childbirth, Chitrali women are not permitted to cook, and certain areas of the house are sealed off to them. But today these customs are not always observed.

Chitrali society is also male-oriented: the birth of a male child is cause for great celebrations, but no such festivity surrounds the birth of a female. Marriages are all arranged, and a woman's physical atributes determine her eligibility. But here there is no bride-price; instead, the girl's father is given a certain amount of money for his daughter's hand.

In valleys like Chilas, women have virtually no individuality; they are so subordinate that it almost seems, according to veteran traveller John Staley, in that area as though they are "socially and morally incompetent and so men are fully responsible for their behaviour."

In regions like Diamer, women's noses are cut off on charges of moral turpitude. Legally, women of the northern areas have few rights. They do not inherit landed property. If there is no male issue, the land is inherited by the brother, his sons and in rare cases even by the son-in-law. Women will only own land if their male members see fit to bestow it upon them.

The lot of the nomadic women in Kohistan, however, is probably the worst. The Gujjars, for example, are treated as social pariahs. And if there are any intermarriages between the locals of the area and these nomads, it is because the Gujjar women are a hardy lot, used to walking long distances, carrying heavy loads and possessing an inborn skill with animals. All of which makes for what is essentially free labour.

Among the northern areas, however, there is one region which is a total deviation from the norm: Kafiristan, known for its amazingly relaxed social order.

In Kafiristan, women are free spirits enjoying the same rights as men. There is an equal division of labour, and an unusually lax sexual morality. Today, however, things are changing as Kafiristan opens up to the outside world.

Disturbing reports are filtering through of men from other province arriving in Kafiristan to purchase women, for either a night or week's pleasure, or for keeps. The impoverished Kafirs have apparently come to terms with the commercial outside world, and are willing to barter their most precious commodity - beautiful Kalash women.

Changing Faces

Who is today's urban Pakistani woman? Is she the middle-class housewife of TV ads, eternally smiling and elegant as she waits on her husband and takes care of her children? Is she the factory worker, the sweepress, the dhoban, performing menial jobs for meagre wages?

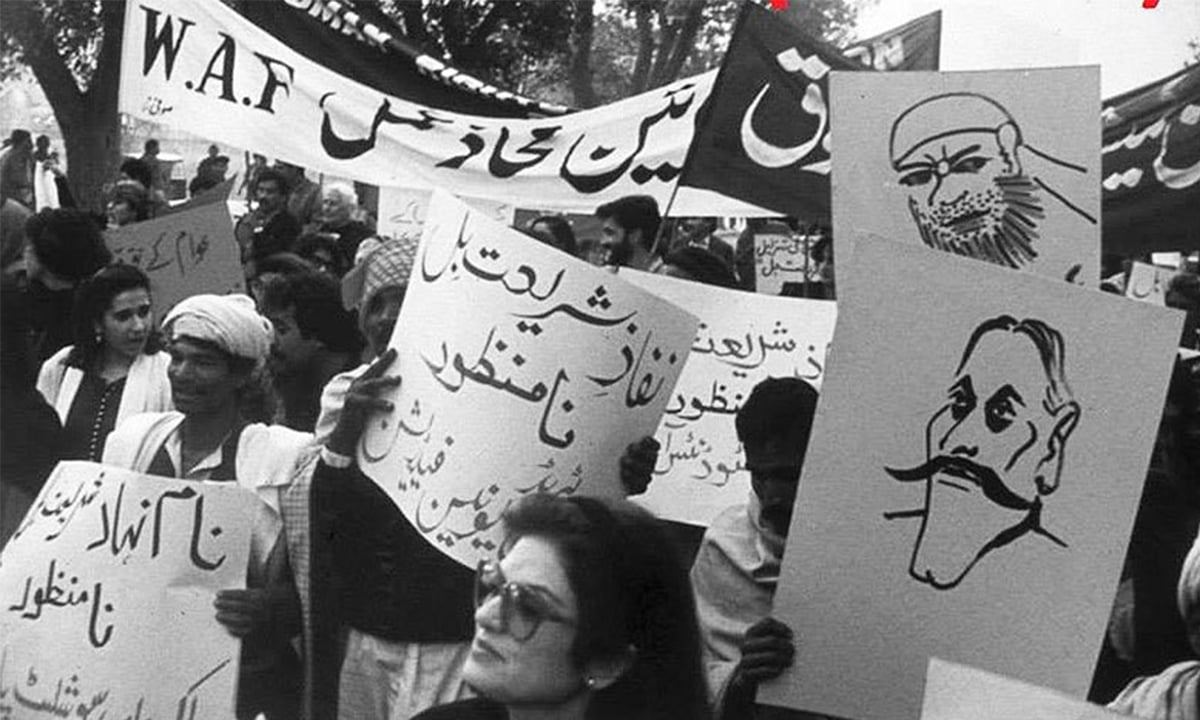

Or is she the recent migrant from a rural set-up, timid and confined to her one room house, but aware of a more liberal environment beyond her doorstep? Is she the educated, westernised, independent and vocal professional, a member, perhaps, of WAF? Is she the APWA begum doing good works, or the sophisticated at coffee parties and lavish dinners?

Unlike the rural Pakistani woman, her urban sister has many faces. In the cities and towns, the polarity of feudal society — wadera/chaudhry and peasant and the rigidity of tribal society, are replaced by a more flexible plurality.

Increasingly, despite the best efforts of obscurantism, urban women are merging into the public world — albeit a world in which reactionary attitudes to woman have been sanctioned by official philosophy and enshrined in legislation.

Women work, everywhere, whether they are in rural areas or cities. But their major economically productive activities are not even recognised, let alone rewarded: housework, child rearing, fetching water, and generally helping as unpaid hands. According to the State of the World's Women Report 1985, if the value of housework is calculated it would amount to nearly half the national income of a country. This devaluation of housework places women at a disadvantage, since it is the occupation of the overwhelming majority.

Urban women engaged in "economically productive" work (i.e, paid labour) face many handicaps. The range of opportunities available to them are extremely limited, due to socio-cultural prejudices, limited educational and training facilities, and the absence of institutionalised child care.

According to some surveys, 60 percent of working women are either professionals, such as teachers and doctors, or unskilled labour. Barely 0.8 percent work in administrative and managerial positions.

Today, few city households survive on a man's salary alone. In fact, many working-class women find that the shoe is on the other foot; while she slogs as a sweepress, a masi or an ayah, the man spends his time and her money on drugs, cards and other women.

On the whole, women workers, constituting the bulk of the labour in such sectors, enjoy no legal rights and are paid not according to any labour laws but by the ‘going rate’ which tends to stay static for years or fluctuates downwards in times of labour surplus. None of the rules regarding permanent employment, bonuses and leave apply to them, nor are they capable of demanding them; most of them are unaware of their rights.

The upper middle-class woman, on the other hand, no longer restricts herself to the two traditionally 'noble' professions: teaching and nursing. She is attempting to break into new areas. A whole new breed of small entrepreneurs running boutiques, beauty parlours and the like have emerged, and their success is encouraging an increasing number to follow suit. A handful of women have even managed to reach the top as technocrats (there's a woman shipbreaker too).

The lower-middle class sections of society, who constitute the majority, work as packers, seamstresses, cutters, either at home or in factories - under appalling sweat-shop conditions.

"My husband believes we work at tables, on high stools, wear white overalls, eat our meals in a decent dining hall and have only women supervisors around," says Shahzadi, mother of two who works in a match factory. "Instead we squat on our haunches on the bare, dirty floor, several hundred to a single room. Knee against knee, we eat our midday meal as we work, and put up with crude, ill-mannered male supervisors who insult us and harass us all day. They take a special delight in brushing their legs against ours."

Fisheries, pharmaceutical firms, garment and match factories prefer to employ female hands. Not only are they more efficient, they are less troublesome too. They are more than willing to work at the low salaries usually offered. What's more, they can be cheated out of their actual wages and done out of their allowances — and they wouldn't even know.

On the whole, women workers, constituting the bulk of the labour in such sectors, enjoy no legal rights and are paid not according to any labour laws but by the 'going rate' which tends to stay static for years or fluctuates downward in times of labour surplus. None of the rules regarding permanent employment, bonuses and leave apply to them, or are they capable of demanding them; most of them are unaware of their rights.

The main reason for this is the lack of organised trade unions in most factories which employ mostly female labour. With the exception of a handful of recognised and registered pharmaceutical companies, the rest make their own rules —which are designed to keep their workers from organizing themselves or making even simple demands.

Male workers, though more aware of their rights and not so easily intimidated, find it difficult to take steps to safeguard themselves against arbitrary measure without the cooperation of the majority. Even if they do manage to form a union, the bulk of the women workers most often desist from becoming members of this union, and are perforce made members of the management's 'pocket' union thus jeopardizing their own rights.

Most of these poor women support the management’s policies out of fear of losing their jobs. The more vocal among them could get laid off or face intimidation at the hands of the management's hired hands. One such incident is enough to intimidate the rest.

Another factor that helps the managements of such factories is the extremely low social status of such women. Most women, in spite of being the sole bread-earners of their families, have to maintain a clean reputation.

Just the fact of their stepping out of the sanctity of their homes and working with males makes their conduct suspect, even in the eyes of close family members. Consequently, most women play extra 'safe' and take the unfair treatment without protest.

Cutting them down to size

In a society where access to justice diminishes in proportion to social status, it may seem somewhat irrelevant to protest against legislation which discriminates against women. After all, even with the relatively progressive Family Laws Ordinance of 1962, the lot of most women didn't significantly improve, and they remain victims of well entrenched social discrimination.

But putting a set of laws on the statute books has an influence on the shaping of social attitudes and it is for this reason that the struggle for women's rights has focused on the proposed legislation, which seeks to institutionalise and legitimise an age-old system of repression under the guise of Islam.

The draft legislation initially put orward related to specific aspects of women's rights — the Law of Evidence, the Law of *Qisas* and *Diyat*, the Zina Ordinance, the Hudd Ordinance. It was met by a well-organised storm of protest. In response, the government retreated into an endless debate on the broader issue of women's status in an Islamic dispensation.

As a result opposition to the proposed legislation was diverted into hairsplitting arguments over meaningless issues, many of them frivolous. In effect the regime bought time for itself: the real issues were obscured.

In actual facts, only a few laws discriminatory to women have been passed. But those few are lethal, laying down the basis of the secondary status and discriminatory treatment being meted out to women at present.

The government has created history by doing away with the differentiation between rape and adultery. By blatantly flouting the Quranic requirement of four witnesses to an act of adultery, and assuming guilt on the basis of pregnancy, the government has left rape victims vulnerable to the charge of zina.

At the same time it permits rapists to get off scot-free for lack of evidence — a benefit of doubt not extended to women. In less than half a decade, an atmosphere of insecurity has been deliberately and effectively introduced to justify male domination, disguised as "protection".

The primary object of enforcing a new law of evidence is not to degrade women's status as a witness but to increase the state's interference with the judicial process and to convince the masses that the promise of an alternative to people's demand for a radical socio-economic order was not without substance. Fortuitously, the only change in the old law of evidence consistent with the entrenched authority's interest was at the expense of women's rights.

Other impediments to women's opportunities and mobility have been effected by decree or tacit understanding: no postings abroad in the foreign service; no decision-making and sensitive posts at home, no participation in international sports meets and no music lessons in girl's schools.

The particular interpretation of Quranic injunctions adopted by the authorities today owes more to expediency and an inherent anti women prejudice than to the spirit of Islamic law. Consequently, enlightened women — and men are beginning to devote their energies to longer – term tactics, rather than an immediate opposition to the present Islamic formulations.

This article was original published as part of the cover story in the September 1985 issue of the Herald under the headline 'A woman's cross'. To read more subscribe to the Herald in print.