The first outgoing shipment of containers carrying Chinese goods departed from Gwadar port on November 13, 2016. The media event was attended by Pakistan’s top policymakers as well as a high-level Chinese delegation. Despite this important first step for the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), many people in Pakistan still approach this project with a sense of cautious optimism.

Nearly all will say CPEC is a game-changer, but some will ask for whom? Others will flag that CPEC is the largest foreign investment into Pakistan, but many will question whether the country will be able to bear the debt burden resulting from it. Some will talk up how the various sub-routes could lift under-developed cities and towns, but others will question whether these sub-routes will even materialise as China is really only interested in the direct route from Kashgar to Gwadar.

To understand the policy motivation behind OBOR, one must realize that China is desperate to maintain its growth momentum, especially with the uncertain outlook for the global economy

This confusion exists because fresh information on CPEC is mostly anecdotal, rather than from a credible official source. People will highlight the increasing number of Chinese in the country (on flights, hotels, shopping malls, etc); the rapid pace of development at Gwadar port; and how the first Chinese shipment moved through different ports of Pakistan to reach Gwadar. Other than the recent shipment, concrete details are scarce.

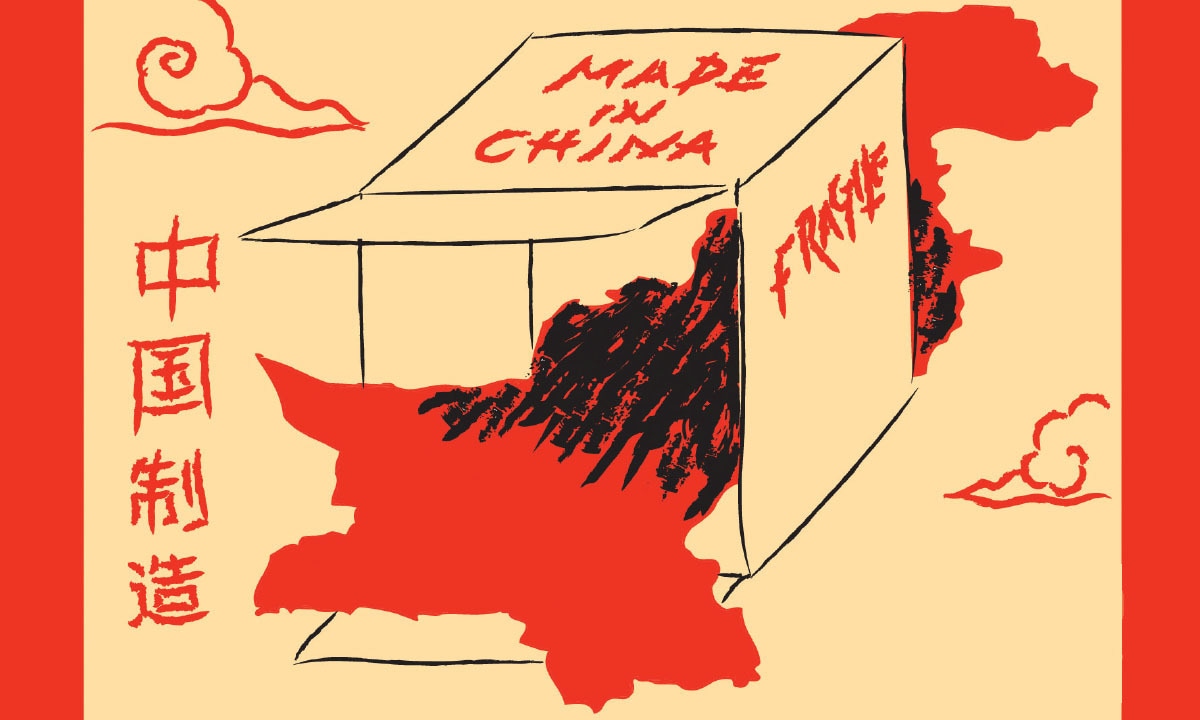

Even so, Pakistanis feel the partnership with China is critically important for the country, though they are unsure whether it will materialise fully. On the other hand, the global reaction to China’s One-Belt-One-Road (OBOR) – of which CPEC is a part – falls into one of two categories: those who think the project is simply not feasible in terms of scale, or the resources needed or the timeline; and those who fear that OBOR is China’s master plan for global domination in the 21st century (see map below).

Observers concerned about OBOR’s feasibility flag the sheer scale of this undertaking, and the apparent disconnect with available funding sources. Bankers will highlight the inherent risks in long-term infrastructure projects, which are compounded by the large number of participating countries. They will focus on financial/trade guarantees, regulatory reach/enforcement, and legal cover and recourse.

While none of these misgivings are unreasonable, we believe they fail to consider several key points. But the basic issue raised by sceptics is entirely legitimate.

So the 46 billion dollar question is whether these fine-print concerns could sink the project. Is the devil really in the details?

What China seeks from OBOR

To understand the policy motivation behind OBOR, one must realise that China is desperate to maintain its growth momentum, especially with the uncertain outlook for the global economy. In fact, if China’s economic growth slows significantly, there are legitimate fears this could spark social unrest and political instability.

In our view, the challenges facing Chinese policymakers could be ranked as follows:

Secure shipping lanes. As the world’s largest importer of oil and gas, China needs to ensure that its shipping routes are not vulnerable at the choke point – the Malacca Straits. Hence, Corridors 1 and 2 of OBOR have immense strategic value for China, not just for fuels and minerals, but also to access Central Asia, the Middle East and Africa.

Develop Western China. While the coastal areas are largely developed, Western China is somewhat neglected. For political harmony, policymakers need to focus on Western China, which explains why Corridors 1, 2 and 3 of OBOR originate out of the Western provinces.

Use China’s spare capacity. Building physical infrastructure has fueled China’s economic growth. With growing concerns that policymakers may have over-invested, China’s installed capacity in steel, cement, bulk chemicals and heavy machinery, is now under-utilised. Building infrastructure in neighbouring countries would be a convenient way to use this spare capacity.

Create new export markets. China perhaps realises that exports to the member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), which have been driving its economic growth, may continue to fall. In effect, it needs to cultivate new markets in Africa and Central Asia, which have significant growth potential.

Create goodwill with neighbouring countries. OBOR entails establishing training institutes and schools in participating countries, which should support the project and be mutually beneficial.

While it is clear that China has to be ambitious, OBOR may not be quite as ambitious as it appears. For example, China may not deliver all six corridors, these corridors may not extend as deeply as envisaged, and each corridor may not include roads, railroads and pipelines as currently planned. But even half of the currently planned OBOR network would go a long way towards securing what China needs.

In fact, we believe there is a latent priority within the six OBOR corridors, with Corridor 1 and 2 on top of the list for strategic reasons. This may be why Corridor 1 (CPEC) has been the first order of business for China under OBOR. Taking a staggered approach makes sense, as it limits the resources that have to be committed upfront. Furthermore, negotiating the first two corridors is likely to be less problematic for the Chinese (compared to Corridors 5 and 6) as there are fewer participating countries in Corridors 1 and 2 (Pakistan, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan and Iran) -- and some of these countries do not enjoy close ties with the United States.

China’s unique approach to economic reforms

Many third world countries were more developed than China in the 1970s. In light of this, China’s current standing in the global economy clearly reveals why its economic transformation is considered a miracle. After Tiananmen Square in 1989, China embraced economic reforms with even greater fervour.

The architect of this accelerated growth was Deng Xiaoping. In 1978, Deng challenged the Chinese to double China’s economy by 2000 and make China a middle-income country by 2050. China far exceeded his expectations when it overtook Japan to become the second-largest economy in 2010. Deng’s heuristic (learning-by-doing) approach to economic reforms defied the collective wisdom of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

It is somewhat ironic that the development strategy advocated by the Washington Consensus, under which the World Bank and IMF operate, is far more ideologically burdened than the one used by Communist China to reform its own economy. Compared to Pakistan, the Chinese were far more practical – and result-oriented – in their approach to economic reforms.

Most importantly, China displayed the political will to change. But political will, while essential for the success of reforms, is not enough. An effective strategy is also needed and China used a novel one that yielded unprecedented results.

Bo Qu, a visiting scholar at Princeton University, highlights two key characteristics of China’s economic reforms since 1978.

It is somewhat ironic that the development strategy advocated by the Washington Consensus, is far more ideologically burdened than the one used by Communist China to reform its own economy.

First, economic reforms do not proceed according to a well-defined blueprint. Qu states that experimentation is a fundamental part of China’s policy formulation, and the process is primarily driven by specific problems encountered during implementation. In effect, the real focus should be on solving practical problems, instead of persisting with ideologically appealing, but ineffective institutional arrangements.

Second, China’s reforms were gradual and incremental, without hard timelines. Qu states that incremental reforms reduce adjustment costs as policymakers are able to balance the pace of reforms with social stability.

Despite starting as an under-developed agrarian economy in the late 1970s, China did not approach the international financial institution (IFIs) for policy advice or financial assistance. The stark contrast between this approach and Pakistan’s experience since the late 1980s cannot go unnoticed. Although Pakistan has been working to restructure its economy for the past 25 years, many would argue that little has been achieved.

China’s Family Production Responsibility System (FPRS) is a good example of the heuristic approach to economic reforms. Before this, China had communal farms with strict production quotas, where even meals were a group activity. The FPRS (which is still in force) allowed individual farmers to rent arable land from the government, in exchange for a specific quota of produce/crops. The rent was paid to the local government.

This simple idea, which effectively permitted farmers to sell surplus produce in village markets, was first implemented in specific provinces in the mid-1970s. When positive results were realised, these experiments were carried out with different crops, and then replicated in other provinces of China.

The FPRS was formalised as policy in 1978 – by 1984, 99 per cent of China’s total agricultural production was incentivised by the private gains of individual farmers. The scale of this change can only be appreciated when one realises that China’s rural population was about 800 million to 850 million people at the time.

This policy alone lifted most of China’s population out of poverty.

China’s success with large-scale economic transformation suggests that it would be an ideal partner to execute CPEC. But even more importantly, China’s tried-and-tested approach to reforms, which is incremental and open to change as the situation evolves, suggests that a lack of concrete details is not cause for alarm. This appears to be how the Chinese prefer to work.

Is OBOR a plan for global domination?

We disagree with the perception that OBOR aims for global domination. First, the specific focus on Asia (effectively ignoring Africa and Latin America) does not reveal global ambitions; and, secondly, since China is the third-largest country by landmass and the second-largest economy in the world, any of its long-term strategy – by definition – will be on a “global” scale.

What is harder to explain is China’s policy in the South China Sea. For a country trying to downplay the perception that it seeks to challenge the US for global domination, China’s strategy in Asia Pacific is surprisingly aggressive. However, changing one’s perspective could explain China’s orientation on this issue.

The Asia Pacific region has a significant US military presence. American bases in Japan and South Korea can be traced back to WWII and the Korean War, but have lost their tactical importance with the end of the Cold War. Furthermore, the continued US presence in Australia, the Philippines, Thailand and the Indian Ocean has the potential to disrupt trade flows destined for – and originating from – China. Since China’s hard power comes from its trade flows, the Chinese are justifiably concerned that a stand off with the US, on any issue, could easily strangle its domestic economy.

The geopolitical dimension of CPEC

While OBOR may not be a plan for global domination, it does seek to change the global status quo. Creating a physical corridor to the Arabian Sea will give China direct access to a deep-sea port that is close to the largest hydrocarbon exporters and a shortcut to Europe, the Middle East and Central Asia.

One must consider how this project challenges the global status quo, the US control of global shipping lanes and India’s ambitions to control the Indian Ocean. The growing tension between the Asian giants (China and India) and the hostility between Pakistan and India explains why CPEC is so strongly opposed by India.

The resistance to Gwadar becoming a fully functioning port is perhaps being reflected by the troubles in some parts of Balochistan — specifically targeting the Pakistan Army and local law enforcement agencies. These terrorist attacks may be an effort to undermine CPEC.

For a country trying to downplay the perception that it seeks to challenge the US for global domination, China’s strategy in Asia Pacific is surprisingly aggressive.

Although Pakistan’s support for CPEC is clear from the army’s active role in guaranteeing security and the endorsement by Pakistan’s main political parties, if the placement of the various routes is hampered by bureaucratic red tape and provincial self-interests, the key Gwadar-Kashgar corridor could be the only route that will be built.

This “CPEC-lite” will fulfill China’s needs, but will not create the economic spillovers the other routes promise.

In the context of the geopolitical prize that is Gwadar, the following is a simplistic assessment of CPEC: China finances and builds the project, while Pakistan pays in terms of social and political disruption, and the loss of innocent lives. Given the strategic importance of the Gwadar-Kashgar corridor to China, this component of OBOR will surely be completed because it is motivated by more than just economics.

This is about securing China’s trade routes and allowing it to position itself in the Arabian Sea.

We believe this partnership with China could be the key factor that will place Pakistan’s economy on a more sustainable path forward. As China targets Central Asia, the Middle East and Africa as part of its strategy for the 21st century, it simply cannot afford to have an economically unstable partner in CPEC.

This geopolitical compulsion should generate the political will to undertake tough economic reforms in Pakistan and also ensure that CPEC is sustainable and profitable for the country.

Mushtaq Khan is Chief Economist at Bank Alfalah and holds a PhD from Stanford University.

Danish Hyder is a research associate at Bank Alfalah and holds a degree from Vassar College in New York. These are the views of the authors and not the bank.