Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) was scrambling to stitch together a coalition government in Islamabad on February 28, 2008, 10 days after emerging as the single largest party in the National Assembly. The party had lost its leader, Benazir Bhutto, in a gun-and-bomb attack on an election rally at Rawalpindi’s Liaquat Bagh only two months earlier. Now her husband and successor as the party head, Asif Ali Zardari, was faced with a problem: who could he trust with the post of prime minister?

The natural front runner for the slot was Makhdoom Amin Fahim, the soft-spoken poet-pir from Hala in Sindh. He was head of the Parliamentarians version of the PPP through one of the party’s most difficult times, after the second Nawaz Sharif government in the late 1990s had forced Benazir Bhutto into self-exile and put Zardari behind bars on corruption charges. Even an offer from General Pervez Musharraf to become prime minister after the 2002 general election had not lured the Makhdoom of Hala into changing his loyalties.

Zardari did not have a very high opinion of Fahim — as is shown in the situation reports sent by the United States embassy in Islamabad back to Washington DC. According to the whistle-blower website WikiLeaks, the US ambassador at the time, Anne W Patterson, told her bosses back home that Zardari viewed Fahim as personally weak, lazy and a poor administrator who lacked the requisite skills to run a government.

Patterson’s classified memos inform us that the PPP co-chairperson seemed to be backing Shah Mehmood Qureshi even before the general election had taken place. Qureshi, after all, was the PPP’s candidate for the post of prime minister after the 2002 general election when Benazir Bhutto was still alive and her party was just a few National Assembly seats behind the Pakistan Muslim League–Quaid-e-Azam (PMLQ), which eventually formed the government.

His arch-rival from their hometown, Multan, Yousuf Raza Gilani, according to the leaked US correspondence, always came up as a less likely option in Zardari’s discussions with Musharraf’s National Security Adviser Tariq Aziz and the then Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) chief Lieutenant General Nadeem Taj — both of whom were negotiating a power-sharing deal with him. When Zardari told Aziz that he was considering Qureshi as a candidate for prime minister, the latter was ‘unenthusiastic’. He thought that “Qureshi would not work well with other parties, was very ambitious and might threaten Zardari’s authority.”

When the moment to make the final choice arrived on March 24, 2008, Zardari picked Gilani to head the government. Qureshi was made the minister of foreign affairs.

It was the second time after 2002 that he had come within a whisker to becoming the prime minister, ever since he had fought and lost a local government election to a younger brother of his other political rival from Multan, Javed Hashmi, in 1983. Having turned 60 this year, will Qureshi ever get that close to the top job again?

Also read: Why Pakistan needs a foreign minister

According to Lahore-based journalist and political commentator Sohail Warraich, Qureshi has been “grooming himself for the job ever since he joined politics”. And, Warraich argues, he has what it takes to be prime minister: “He is one of the most well-read politicians in Pakistan, comes from a known religious family, is intelligent and has a strong grip on foreign affairs, economy, agriculture, etc. He understands Punjab’s politics and remains untainted by charges of moral and financial corruption. He knows how to communicate with local and international audiences and is close to the country’s powerful establishment.”

Anyone with these credentials would want to have the post of Pakistan’s chief executive. Little wonder then that most people who know Qureshi have found him ambitious.

He easily alienates people around him because of his feudal, aristocratic attitude,” concedes one of his loyal voters.

One of them, Ambassador Patterson, narrated to her superiors in Washington DC that Qureshi had been promoting himself as a possible prime minister in his meetings with diplomats. She, at the same time, described him as an independent person. “If I am prime minister, I am not going to be Zardari’s ‘yes-man’ ... I am loyal to the party and to Zardari, but I am my own man,” a leaked US embassy document quoted him as having told US officials. He is said to have explained to them that, if he were made prime minister, he expected to be able to choose his own ministers and would not passively accept directives from Zardari working from behind the scenes.

Also read: Pakistan's foreign policy betrays deep domestic insecurities

To Patterson, Qureshi was a polished, experienced, pro-West politician. “Qureshi … is a smooth and sophisticated interlocutor, and he appears sincere in professing that his and PPP’s interests are congruent with those of the United States. He believes PPP has more in common ideologically with Musharraf than with Nawaz [Sharif]” — whose Pakistan Muslim League–Nawaz (PMLN) he had quit after about six years of association, to join the PPP in 1993.

On January 27, 2011, almost three years after the PPP’s fragile coalition government had taken over, Raymond Davis, a private security contractor engaged by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), shot down two young motorcyclists on Lahore’s busy Ferozepur Road.

The police arrested Davis for the murders and sent him to jail. The US government demanded his immediate release, contending he enjoyed diplomatic immunity and was protected from criminal prosecution under international conventions. But, blown up by 24/7 television news, the incident triggered a strong public outrage. Political parties and religious and militant groups joined the foray to whip up anti-American emotions. Protests were held almost on a daily basis and fiery speeches were delivered, threatening the government against releasing Davis under any American pressure.

Also read: Which has been Pakistan’s most significant political schism?

The case soon evolved into a much bigger issue about the presence of a large number of CIA operatives on Pakistan’s soil. Zardari – who by then had become the President of Pakistan – and Husain Haqqani, Islamabad’s ambassador in Washington DC, were blamed for freely issuing visas to these operatives.

There were speculations that the military establishment was pulling the strings from behind the scenes to hit back at Zardari and Haqqani for their perceived proximity to US authorities. It was amid this political melee that the Foreign Office issued a statement, presumably at Qureshi’s behest, that Davis did not enjoy blanket immunity from trial because he was not a diplomat according to Pakistani records. This was the last thing that a beleaguered Zardari expected from his government’s top diplomat.

Also read: Satire: Diary of Nawaz Sharif

A few days later, the PPP’s central executive committee decided to trim the size of the federal cabinet. There was talk of the reshuffle being a ploy to bring in a new foreign minister.

Qureshi decided to skip the oath-taking ceremony of the new cabinet after he came to know that he had been stripped of his old portfolio. “He declined to accept the water and power ministry offered in the new cabinet because he knew that he was being punished for the statement on Davis’s diplomatic status,” contends a Multan-based political observer. “By accepting a new cabinet portfolio, he would not only have accepted the reprimand by Zardari but also invalidated his own stand on the issue of diplomatic immunity for the American operative.”

Some suspect the Foreign Office statement and Qureshi’s refusal to join the reshuffled cabinet were both prompted by the then ISI director general Lieutenant General Ahmed Shuja Pasha. “Qureshi was, and still is, very close to Pasha,” claims an Islamabad-based political analyst who personally knows Qureshi. “That was the time when the military establishment was trying to politically isolate President Zardari for his government’s unrestrained support to the US at the cost of what the establishment considered the country’s sovereignty,” the analyst adds without wanting to be named. “General Pasha had a major role to play in that.”

Qureshi portrayed his unceremonious removal from the cabinet as a “selfless act of defiance” to protect “national honour”. It suddenly catapulted him into national limelight. From being one of the 54 ministers and advisers in Gilani’s cabinet, he became one of the most sought-after politicians in the same league as Sharif, Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) Chairman Imran Khan and, of course, Zardari himself.

In spite of the public snub from the PPP leadership and insults hurled at him by second tier party leaders, Qureshi did not quit the party immediately. He initially tried to woo the anti-Zardari elements within the party by questioning the PPP’s alliance with the PMLQ. Many speculated that Qureshi was trying to foment a revolt within the party and create a group by gathering alienated party workers and leaders around him.

By the time he made up his mind to leave the PPP, he was being wooed by both Sharif and Khan. The former hosted him twice in his Raiwind estate, inviting him to join the PMLN, but he chose to wager his bets on PTI instead — a party that many in the Sharif camp saw as being helped by Pasha as a possible challenge to their hold on Punjab.

Qureshi is the custodian of the shrines of Bahauddin Zakariya – the founder of the Suhrawardiyya Sufi order in the subcontinent – and his grandson, Shah Rukn-e-Alam, in Multan. British colonial rulers always sought the support of his family to strengthen their rule — as did the military dictators after 1947.

One of his ancestors – after whom he is named as Shah Mahmood Hussain Qureshi – is said to have sided with the British in the 1857 War of Independence. “In return, he was allotted huge lands in Multan. Later on, his family joined the [pro-British] Unionist Party from whose platform [Qureshi’s] grandfather Makhdoom Mureed Hussain Qureshi fought the 1946 election before independence,” says Shakir Hussain Shakir, a Multan-based author and political analyst.

“After independence, Qureshi’s father [Makhdoom Sajjad Hussain Qureshi] carried on with the family’s tradition of political correctness and tried to align himself with parties close to the establishment,” says Shakir. “When General Ziaul Haq imposed martial law in 1977, Makhdoom Sajjad Hussain Qureshi joined the dictator who inducted him to [his hand-picked] parliament, Majlis-e-Shoora. Later, he was made a senator and then appointed Governor of Punjab.”

Also read: The great divide: Politics for the poor has gone out of fashion

The family’s love affair with the powers-that-be continued apace after that. In his book, Haan! Main Baghi Hoon, Hashmi writes that General Hamid Gul, who was corps commander of Multan at the time and who later became a controversial ISI chief, called him to his office in the run-up to the 1985 partyless general election and advised him to withdraw his candidature for a Punjab Assembly seat (which included Hashmi’s ancestral Makhdoom Rasheed town near Multan) in favour of Qureshi. The conversation took place in the presence of Qureshi’s father. Hashmi refused to oblige. When the results became known at the end of the polling day, Qureshi had polled almost twice as many votes as Hashmi did for the provincial assembly even though the latter won the National Assembly seat from the same area.

An alumnus of Aitchison College, in Lahore, and a Cambridge University graduate, Qureshi joined the PMLN before the 1988 general election. Two years later, he was made minister of finance in Chief Minister Ghulam Haider Wyne’s Punjab government. Just before the 1993 general election, he joined the PPP after Sharif declined to make him PMLN’s candidate for a National Assembly seat that included Makhdoom Rasheed where Hashmi wanted to contest. Qureshi easily defeated Hashmi to become a junior parliamentary affairs minister in the second Benazir Bhutto government.

“He was disappointed with the PMLN because he believed that Nawaz Sharif’s politics had started only after [Qureshi’s] father had sworn him in as chief minister in 1988, although [Sharif’s] party had not won enough seats to form a government in Punjab,” says a former member of the National Assembly from Multan, requesting anonymity. “[Makhdoom Sajjad Hussain Qureshi did so] despite a telephone call from Benazir Bhutto stopping him.” Sharif did not return the favour.

Another factor was a class conflict between ‘agriculturist’ Qureshi, who was the founding chairman of the Farmers’ Association of Pakistan, which represents big landowners in Punjab, and ‘businessman’ Sharif under whom, according to Warraich, “Punjab’s political power shifted into the hands of the urban elite from the landed aristocracy.”

There was another reason. “In my view, the most important factor that made him quit the PMLN was his ambition. He believed he could not achieve his goals if he stayed with the PMLN,” says a political activist from Multan who claims to be close to both Qureshi and Gilani. “He needed an alternate platform to advance his ambition and the PPP provided him that.” Benazir Bhutto made him the party’s Punjab president in 2007 even when Gilani did not see the decision ‘favourably’.

Warraich, too, believes that the PPP treated Qureshi quite well. “If Benazir Bhutto had made him the Punjab president of the party, Zardari, too, gave him the vital designation of foreign minister at a time when the party needed someone trustworthy in its dealings with the Americans.”

Some PTI leaders say Qureshi ‘advised’ Khan against letting Hashmi into the party.

What, then, made Qureshi quit the PPP? “I think he was not satisfied with a slot in the federal cabinet or with becoming the foreign minister,” says Warraich.

The aforementioned Islamabad-based analyst agrees. “The foreign ministry did not seem to fit in with his long-term political plan, although it immensely helped him show his competence to the public and develop close and personal relationships with powerful US officials like former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and her replacement, Senator John Kerry. He wanted something bigger.”

When Qureshi accused the PPP government of undermining Pakistan’s sovereignty perhaps “he was following the example of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto” who, before founding the PPP, had blamed General Ayub Khan of doing just that in the aftermath of the 1965 war by making peace with India at Tashkent. Qureshi went to the extent of cautioning the “nation that the nuclear programme wasn’t safe in the hands of Zardari”. This, the analyst says, shows “how desperate he was to rise as a popular national leader”.

Also read: General accountability

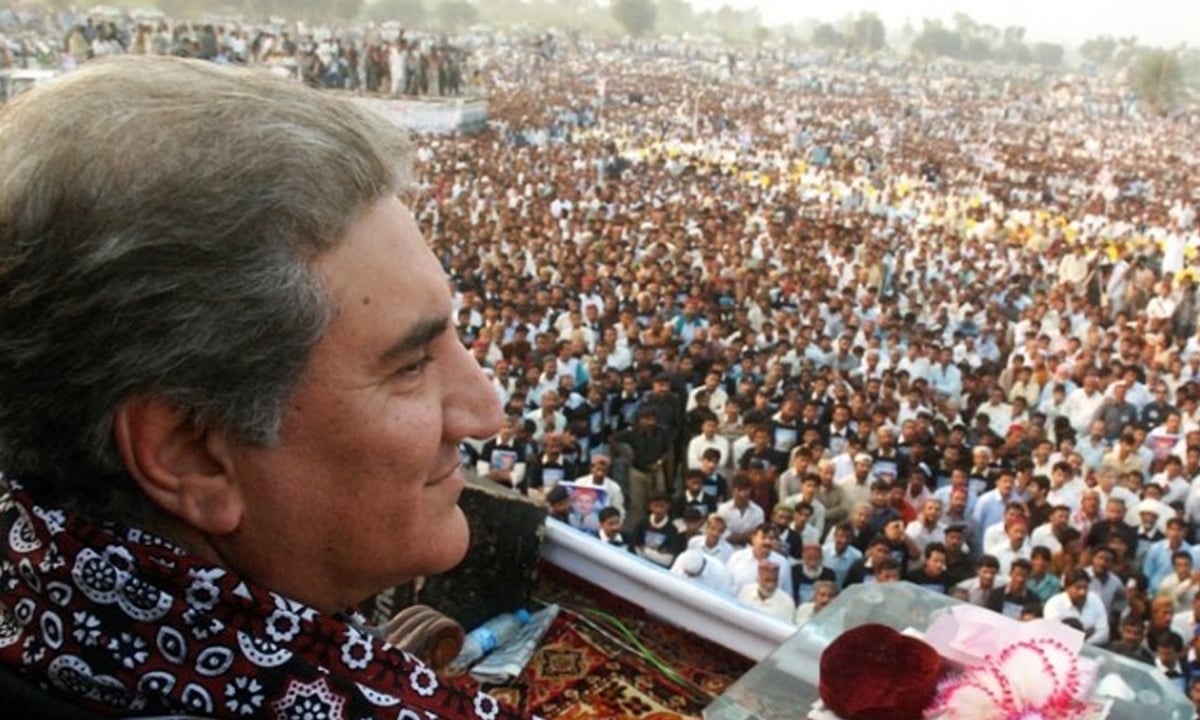

After his exit from the PPP, Qureshi tried many a time to build his image as a popular politician who has grown out of constituency politics. For example, he used Jamaat-e-Ghausia, the organisation comprising devotees of Bahauddin Zakariya, mostly concentrated in Sindh, to organise a large public rally on November 27, 2011, in Ghotki, on the border between Punjab and Sindh, to announce his decision to join the PTI. Later in 2013, he contested a National Assembly seat from Umarkot, again in Sindh, where a large number of his family’s spiritual followers reside. He lost the contest to a PPP nominee, Nawab Muhammad Yousuf Talpur, by more than 13,000 votes.

While Qureshi could not break free of the constituency constraints, failing to win an election away from his ancestral Multan on the back of his family’s spiritual following, he did manage something unprecedented in the process. “It was the first time in the history of Jamaat-e-Ghausia that its figurehead was using it for political objectives,” says Shakir. “His father never did that.”

Qureshi’s only brother, Mureed Hussain Qureshi, later accused him of using the Jamaat’s support and donations from the followers of Bahauddin Zakariya to consolidate his position in the PTI. Mureed Hussain Qureshi also led a failed attempt to oust him as the custodian of the two shrines. “Shah Mahmood is using the names of Sufi saints for political gains. He is encouraging members of Jamaat-e-Ghausia to join PTI. They are wrongly being pushed into politics,” he is reported to have told a press conference in Multan, some months ago. In the 2013 election, the two brothers were in opposite camps — one with the PTI and the other with the PPP.

Qureshi contested the 2013 general election from two National Assembly seats in Multan as well. He lost his original constituency (comprising Makhdoom Rasheed and its adjoining villages) to PMLN’s Malik Abdul Ghaffar Dogar by a margin of more than 17,000 votes. He won from an urban constituency which he was contesting for the first time — mainly on the strength of his party’s popularity.

The constituency politics he was trying to rise above had caught up with him, it seems. Lineage is important in politics but not as much as it used to be, says Shakir. “The custodian of a shrine may have thousands of loyal followers but now he has to personally contact voters to win an election. Times have changed.”

Qureshi’s supporters and critics in Multan agree that he has a feudal ego that impedes his politics — both at the level of constituency and in national politics. “He easily alienates people around him because of his feudal, aristocratic attitude,” concedes one of his loyal voters. “It was his ego that hampered him from creating a personal following within the PPP while he was its provincial president. Little wonder then, that no one followed him when he exited the party.”

Also read: Mind your language — the movement for the preservation of Punjabi

A PTI leader from Lahore expresses similar views. “Qureshi has made more enemies than friends in the party,” he says, speaking on the condition of anonymity.

Some PTI leaders say Qureshi ‘advised’ Khan against letting Hashmi into the party. Similarly, he was not pleased when the former Punjab Governor Chaudhry Mohammad Sarwar joined the PTI. Qureshi is said to have disappeared from the party scene for months after Sarwar was welcomed into its fold. He is also not comfortable with PTI Secretary General Jehangir Tareen and Abdul Aleem Khan, both seen as bankrolling the party. This kind of attitude, according to the anonymous PTI leader “has not helped Qureshi create a strong constituency for himself within the party”.

Qureshi’s differences with Tareen and Sarwar came to a head during a convention of party workers in April this year in Lahore where he accused Sarwar of having made repeated attempts to have him removed as the party’s senior vice-chairman. “I will part with the party if I have to seek a ticket (for election) from people like Tareen and Sarwar,” he thundered at the convention. He also accused the two of trying to hijack the party. “Sarwar and Tareen cannot influence Imran Khan’s decisions. How can these political novices teach us politics? If any rich man thinks he can impose his will on the party, he is mistaken,” he proclaimed.

It was reportedly after this speech that Khan called off intra-party elections, raising speculation that the move was to avert its possible break-up.

Qureshi, according to many PTI insiders, has a knack for making himself controversial. “His present status in national politics does not match with the kind of rifts he has become part of in his party,” says the PTI official from Lahore. “If he has his eyes on a bigger prize, he must keep his feudal ego under control and work with opposing factions in the party to unite it and not to divide it. Or else he may make content himself with always playing the supporting role he now has under Imran Khan.”

That supporting role is something Qureshi has already averted twice. How will it be different the third time round?

This was originally published in Herald's July 2016 issue. To read more subscribe to the Herald in print.

The writer is chief reporter at Dawn, Lahore. He tweets at @nasirjamall.