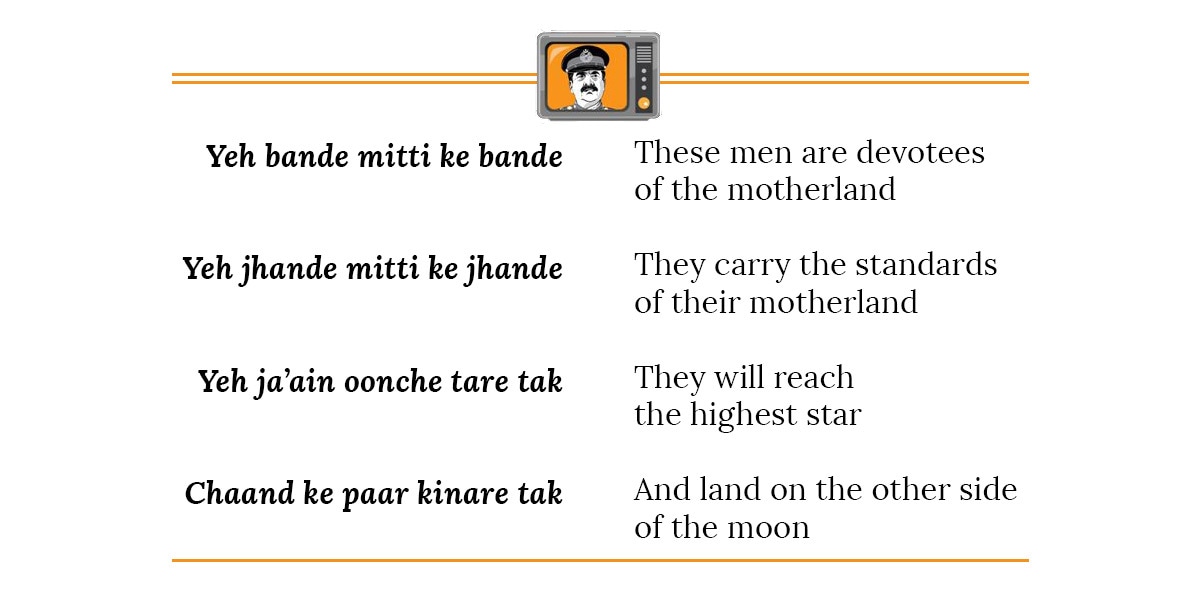

As Atif Aslam croons these lines in his signature lilting style, the accompanying video tells an impressive story of public service and bravery. Captain Ahmed, the fictional protagonist in the video, saves a young woman from mugging in a market and then gets killed in a military operation he leads to rescue children and women from the captivity of what resembles Taliban fighters. The woman happens to be a journalist who, then, puts together the story of Ahmed’s exploits through interviews with his colleagues and his diary entries. Next day, her story is carried on the front page of a newspaper with a very laudatory headline — “Real Heroes of Pakistan”.

In the song, released on April 30, 2013 on what the Pakistan Army calls Youm-e-Shuhada (Martyrs’ Day), the various elements of a public relations juggernaut come together: catchy music, military-style pyrotechnics and a good human interest narrative. It gives a message that the soldiers would want everyone to get: Military officials are out there to help and protect people – both in war and peace – and their story must be highlighted by the mainstream media.

Major General Asim Bajwa, director general of the Inter-Services Public Relations (ISPR), effectively the media wing of the army, explains why there is a dire need for stream-lining the flow of military-related information to the media — mainly newspapers and television channels. “It was June 8, 2014, and Karachi’s Jinnah International Airport had come under a terrorist attack,” he says in a recent conversation. “When I switched on the television, I saw reporters and cameramen standing almost inside the airport. There was no one to stop them from entering into a sensitive zone where fighting was going on; no one to tell them that their reporting could endanger lives,” he adds. “I called a senior official in the federal information ministry; he told me to get in touch with the Sindh government, since the incident was happening in Karachi. I talked to officials in the Sindh government and they said the airport came under the Civil Aviation Authority, which is not a provincial department. I talked to someone at the Civil Aviation Authority and they said their job was limited to ensuring that all flights landed and departed on time.”

Flabbergasted, Bajwa decided to take control. “I informed the chief [of the army staff] and requested him to move the station commander in Karachi to the airport. The station commander immediately shifted all the journalists out of the airport. At the same time, I assured all the news directors at television channels and all the editors at newspapers that they will be getting minute-by-minute coverage.” From then onwards, he would tweet directly to newsrooms across Pakistan, if and when there were any developments at the airport. “When I visited the United States later, they were amazed at how efficiently I had handled the flow of information during that attack,” he says with a hint of pride.

Journalists agree the old ways of reporting about the army and the ISPR have lost relevance. In one major departure from the past, postings, promotions and transfer of senior military officials are no longer a subject of speculation, as was the case in the past. Many journalists bitterly remember how they were mistreated, sometimes even badly manhandled, by intelligence officials in the 1990s only for reporting on high-level staff shuffles in the army. Reports about such shuffles now reach newsrooms as an official press release, mostly delivered as an email or a tweet.

When the need arises for ‘inspiring’ individual journalists into writing something favourable for the military – much like in the song mentioned above – the ISPR prefers to do it from a distance. It has engaged private consultants – some of them journalists-turned-analysts – to coordinate with reporters and desk editors. Managers at some consultancy firms working with the ISPR share with the Herald how they are in touch with a large number of journalists ready to oblige as far as “filing a pro-army” story is concerned.

The military leadership complained to the federal ministry of information technology and PTA about the fake social media accounts created under the names of military and intelligence chiefs.

Whereas in the old system, the ISPR officials had to personally liaise directly with reporters and news editors, now personal access is granted only to a select few — mostly talk-show hosts, opinion writers and editors. Obviously, most journalists are unhappy with the new military-devised hierarchy within their ranks.

A senior ISPR official, however, denies that journalists have been relegated to a secondary status in his department’s protocol. “Our whole system is based on information-sharing with the media and journalists,” he says.

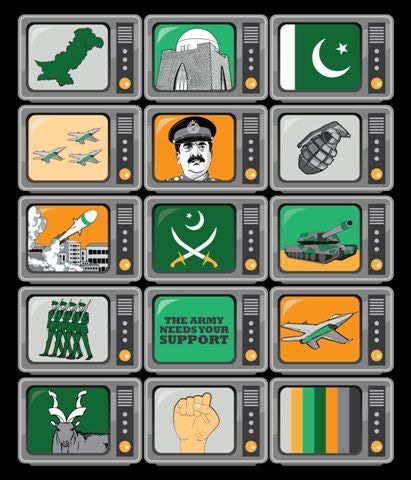

That is true — to the extent that the ISPR does share information with the media. The way that sharing is done and with whom, however, has changed almost entirely – new mediums such as social media forums and websites are being frequently employed and the generation of non-news products, such as songs, plays, documentaries and films, has gathered an unprecedented momentum. The dissemination of most of this digitally produced content bypasses journalists and reaches its targeted audiences directly.

To be historically correct, the ISPR has been generating and disseminating much more than just military-related news reports since its early days after Independence. It always had a publication department, which has published a monthly journal, Hilal, since 2007 (it started as a weekly in 1951 and sometimes in 1952 was turned into a daily newspaper, mostly consumed by the military’s own personnel; it returned to a weekly frequency in 1964). The ISPR has been producing documentary films since the 1960s and releasing songs and other motivational and promotional materials for decades.

Yet, in recent years, the volume of the ISPR’s media production has increased dramatically. In the last five years alone, the ISPR has produced numerous documentaries, a large number of inspirational songs and three major drama serials — besides working on a feature-length film. Bajwa’s Twitter account has 1.31 million followers (and counting) — larger than the daily circulation of the three largest newspapers in the country combined.

Mubashir Zaidi, a senior reporter who hosts a talk show at Dawn News television channel, believes that interacting with newspapers and television news channels has “now become a small fraction of [the ISPR’s] overall job description”.

This song plays as a backdrop to a video showing a slick military operation. A battery of young army officers in combat fatigues charges a militant hideout where a large number of civilians are being held hostage. Equipped with earphones, mouthpieces, night-vision goggles and sniper rifles; wearing protective helmets and kneecaps, these officers look like the epitome of a 21st century Pakistani solider — armed with latest technology and yet selflessly fearless. They carry out an immaculate rescue operation — killing and capturing all the kidnappers and freeing all their hostages unharmed without so much as receiving a minor injury.

The brand development of these postmodern soldiers can no longer be possible without the communication tools that are compatible with their image. And the ISPR is employing those tools to the maximum. The moment a development takes place related to the armed forces — for instance, a military operation in tribal areas, casualties in a clash with terrorists, meetings of the senior military officials among themselves or with other government functionaries and foreign visitors, or even the introduction of some new military toy for the use of the boys in uniform – officials at the ISPR become active through their Facebook and Twitter accounts. News reports are disseminated, photographs are relayed and links for multimedia content are shared instantly.

The number of official social media accounts representing the army is rather small. Bajwa, the ISPR chief, operates his own Twitter and Facebook accounts; his department, too, has one Twitter and Facebook account each; and there is a third Facebook account that represents the Pakistan Army but is operated by the ISPR.

And then, there are some more.

The problem with this ever-changing narrative is that, well, it changes too frequently and too fast – from religion, patriotism and militarism to religious and ethnic diversity and back, in the space of a single song or a play or a movie.

Immediately following General Raheel Sharif’s appointment as the Chief of the Army Staff (COAS) on November 29, 2013, at least 37 Facebook accounts appeared under his name. Many other Facebook accounts appeared simultaneously under the name of Lieutenant General Rizwan Akhtar, director general of the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI).

Apart from these and numerous other social media accounts opened under the names of prominent military personalities and officials, there are countless accounts and pages on Facebook, Twitter and Youtube which actively promote content close to the ideology and the activities of the military. Most of these sites and accounts were instrumental in promoting Raheel Sharif’s credentials as a soldiers’ soldier, right after he became the COAS. This was initially done through a meme showing his ageing mother and asking who would be a nobler woman than her in Pakistan — her husband (Rana Muhammad Sharif), brother (Raja Aziz Bhatti) and the eldest son (Shabbir Sharif) were all majors in the army, the latter two having won the Nishan-e-Haider, the highest military award for gallantry.

In another extremely popular Facebook post, Raheel Sharif is shown walking down a corridor flanked by the Karachi corps commander and the director general of the Sindh Rangers. Their images are juxtaposed to the image of three lions walking side by side. “Never before the life of terrorists have been made so difficult in Karachi,” reads its caption. Many other posts show COAS Raheel Sharif as the acme of efficiency, professionalism and altruistic commitment to the welfare of the people of Pakistan. Through his unwavering will, the readers are told, he is going to rid the country of the twin menaces of terrorism and corruption.

“Of course, General Raheel is a major blessing of Allah for Pakistan. Let us thank Allah for this blessing,” reads another post that carries his photo in full military regalia. In one post, he is shown in the foreground of a scale used as a symbol of justice. The top of the post carries his name, the bottom mentions military courts. “The age of justice is about to dawn. Injustice can never be perennial,” it proclaims.

Sometimes Pakistan’s virtual world seems to be walking in lockstep with Raheel Sharif. If he is meeting soldiers stationed in the tribal areas, his digital supporters rush to portray him as a military commander par excellence who cannot care less about his own safety to be with his men. When he receives the families of the victims of terrorism or the children and widows of the slain military officials at his office in Rawalpindi, the focus shifts to highlighting his compassion as a man of the people. His official tours to places such as Balochistan and Karachi are portrayed as the arrival of a dauntless commander on the scene of a war that nobody was able to win before him. And his parleys with foreign dignitaries are projected as the manifestations of his unbendable patriotism and unparalleled statesmanship.

Other serving and retired military personalities also get a huge amount of favourable traction in cyberspace courtesy websites and social media accounts that actively root for anything linked to the military. When Hameed Gul, a former head of the ISI, died last month, the Internet was abuzz with his exploits, projecting him as a hero who had singlehandedly defeated the Soviet Union. An army general who has sent his son to the front line in the war against terror sometimes earns a similar spate of digital praise. One of the favourite subjects of these cyber warriors is promoting the heroic deeds of young army officers who have laid down their lives while fighting against terrorists. Sometimes, their spartan lives are shown in contrast to those of “luxury-loving, inept and corrupt politicians”.

Apart from promoting the military leadership, some of these accounts are active in generating a single-track hype over important issues of national security and foreign policy. The military is shown to be fighting an unequal war against a foreign enemy which has evil designs against Pakistan and is willing to employ any financial, intellectual, ideological, cultural and military means to destroy our country. Some Pakistanis are then presented as internal enemies, collaborating and conniving with the external enemies of the state. These mostly include politicians, media persons, writers, actors and the odd religious leader.

A Karachi-based social media expert, who wants to remain anonymous due to the sensitivity of the subject, says such content is mostly generated by social media accounts and websites set up under obscure identities. PakArmyChannel, for instance, is present both on Youtube and Facebook. It reveals little about the identity of its operators except that they may be based in Germany. The channel carries hundreds of videos with pro-army songs, news reports and other multimedia materials related to the military. And it is just one of innumerable accounts with obscure identity. “There is no way we can know the origin of these accounts. These cannot be traced back to any real person or organisation,” says the expert.

For its part, the ISPR has made it clear that it has nothing to do with such obscure accounts and sites. “We have got nothing to do with any kind of negative or malicious campaign against anybody,” says a senior ISPR official when asked about the contents of such Internet-based forums and platforms.

We are told, on the other hand, that the military leadership complained to the federal ministry of information technology and the Pakistan Telecommunications Authority (PTA) in December 2014 about the fake social media accounts created under the names of military and intelligence chiefs. The PTA is said to have taken up the matter with Facebook management, leading to deletion of many of those accounts – albeit temporarily.

Regardless of whether the ISPR and the military own those websites and accounts or not, more often than not, they project views meant for massaging the military’s institutional ego and the personal egos of its leaders. At many popular forums, both on the Internet and within the social media, discussion is raging whether Raheel Sharif should get an extension in his tenure as the COAS; if yes (for most discussants that is the only and obvious answer) then by how much should his service be extended beyond November 2016 when he is set to retire — for three more years, for five years, or for life. A web page that favours a five-year extension had attracted 33,000 likes by the end of the last month.

This prompts the anonymous social media expert to make a controversial observation. “Such campaigns are calculated moves.”

Brigadier (retd) A R Siddiqi, who has worked in the ISPR for more than 20 years before retiring as its head in 1973, argues that “such image-building” often “happens under official direction and with the full weight of the state authority.” In the preface to his 1996 book, The Military in Pakistan: Image and Reality, he writes about the problems with such exercises. “The image may not always be unreal or untrue, but it hardly ever reveals the entire picture. In fact, the need for the image may arise only when reality by itself is not good, substantial or weighty enough for projection in its true form and colour.”

Elsewhere in the book, Siddiqi offers a historical parallel to make his point. When Major General Muhammad Azam Khan imposed martial law in Lahore in March 1953, in the wake of anti-Ahmedi violence, army officers “were treated and projected as popular heroes and leaders”. He writes: “Everyday news photographs showed them presiding over public functions, addressing people, touring city areas for on-the-spot surveys, opening new markets and public buildings.”

In an earlier chapter, Siddiqi explains that, as a result of sustained image-building exercises, the “military emerges as a super social elite answerable to none except its own commanders, at various levels, and ultimately to the commander-in-chief (chief of the staff)”. The development of such personal allegiance may trigger events that lead to the overthrow of the civilian authority and the start of a military dictatorship. “In turn, the service chief, depending on his personal ambition, exploits the loyalty of all ranks to seize political power and become a dictator … Sustained image-building may both precede and follow military coup d’etat,” warns Siddiqi.

Released in the immediate aftermath of a terrorist attack on an army-run school in Peshawar late last year, these highly evocative and emotional lines are complemented by a video that shows children rushing to schools to take up the pen and the book even when faced by naked threats of terrorism. The same auditorium where the terrorists had killed close to 150 individuals is brimful of students towards the end of the song; the school principal appears at the climax and sums up the mood of the whole song in a defiant one-liner: “Welcome back to school.”

The song was a major official effort to create a narrative that could paint the terrorists who had committed the brutal school attack as the well-deserved targets of national hatred and retribution. Its lyrics did not focus on religious themes; children’s innocence, love for the motherland, courage in the face of adversity, determination to carry on with education irrespective of the threats and optimism about the future were considered enough to mobilise public opinion against an enemy difficult to portray as an unmitigated evil.

Soon enough, the propagandists on the other side found the flaws in this approach and launched their own version of the song exploiting those flaws to the hilt. They showed children reading religious texts and painted the generals of the Pakistan Army as getting money from the imperial powers to kill the true followers of Islam. The song ended on an ominous note: a man’s voice says, “Welcome back to school” and the sound of bullets being fired follows after a brief pause.

In an Islamic republic that has a self-professed objective to preserve and promote the Islamic way of life, the Taliban song posed a serious challenge to the ideologues of the state: who owns the religious and national narrative and, if there are to be multiple national narratives, which one should enjoy preference and precedence?

An ISPR documentary, The Glorious Resolve, released in 2011, pointed to the same problem. It showed the slogan of Allah-o-Akbar at the end of a speech by a Taliban commander also marking the opening of the next scene in which Pakistani soldiers were offering prayers. Fighting an ideological battle with an enemy which shared that very ideology, and indeed claimed to be representing it better than a ‘Westernised’ military and political elite, seemed almost impossible.

It was much easier to confront the narrative of an external enemy — such as a hostile neighbour, an overweening superpower or a foreign intelligence agency. Confronted with a religion-inspired extremist militancy in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and the tribal areas, an ethnic nationalist insurgency in Balochistan and a deadly mix of crime, corruption and politics in Karachi, the manufacturers and guardians of the national narrative have been highly confused. They have been finding it extremely difficult to bind all these strands together in a single narrative thread that could help them galvanise the nation behind those fighting against the forces harming and hurting Pakistan.

In the recent past, the makers and builders of the national image kept their efforts abreast with the military’s objectives and challenges. Intent on promoting an insurgency in the Indian-administered Kashmir, the ISPR collaborated with Pakistan Television Corporation (PTV) in the late 1980s and the early 1990s and came up with plays such as Mujahid that highlighted how and why it was justified for Pakistanis to fight against India in Kashmir. Ujalay Se Pehle was another army-inspired play in those decades, revolving around military operations against dacoits and bandits in Sindh’s river belt areas.

In the 1990s, a new type of television serial was also produced to show young military officers much like any other youngster of the era — fun-loving, romantic and upwardly mobile. Both Sunehray Din (aired in 1990) and Alpha Bravo Charlie (broadcast in 1998) were attempts at giving the military an urban ethos that it lacked until then. The reason: the military was engaged in street battles with an urban youth militancy in Karachi.

Since the early 2000s, however, the narrative has been struggling to catch up with the situation at the battlefront. A religion-inspired militia of mainly madrasa students and teachers also proved quite adept at using the same religious, patriotic and militaristic symbols that the military has been using — the Taliban had the advantage of portraying themselves as the underdog fighting against infidel imperialists and their local lackeys. The military’s media managers were perplexed over how to counter their Islam-soaked propaganda.

In 2008-2009, they unsuccessfully tried to play the victim card. They produced small docudramas about the heirs of the victims of terrorism and tried to convince newsroom leaders in newspapers and television channels that highlighting their stories was a national and moral duty in the fight against religious extremism. There were few takers, if any at all.

The military’s public image was at its lowest then. Having spent almost a decade under General (retd) Pervez Musharraf’s rule, people had seen the military leadership become part of all kinds of convenient political arrangements to ensure its stay in power. On the military front, the flip-flop combination of battle-by-day and peace-accords-by-night with the Taliban had led some people to believe that the two sides were not really interested in fighting it out against each other. Others believed the military had become so accustomed to the luxuries of politics and power that it was no longer the famed fighting machine it once was known to be.

When, finally, the military started an operation clean-up in Swat in 2009, its media managers thought that broadcasting stories of heroism and sacrifice was the best way to mobilise popular support for the campaign. This led to the production of drama serial Khuda Zameen Se Gaya Nahin, first aired on PTV and Hum TV in 2009-2010.

The objective of the serial, say officials closely associated with its production, was to counter the Taliban’s narrative. Its producers were told “we have to erase that narrative from the minds of the public”. Written by Asghar Nadeem Syed and directed by Kashif Nisar, Khuda Zameen Se Gaya Nahin was “rich on the feelings of nationalism, sacrifice, valour and fighting spirit.” It promised, according to its Facebook page, “to give hope to our audience and unite the nation.”

But it was only after the Taliban were defeated in Swat that the military regained some of its lost grip on the public’s imagination. Soon, it was back on the offensive — narrative-wise, that is. Even during the Swat operation, the military and its brand managers had found that an easy way to mobilise public opinion against the Taliban was to highlight their inhuman brutalities and excesses, and portray them as agents of the enemy.

The Glorious Resolve, for instance, showed the Taliban commander in Waziristan talking to someone on the phone negotiating the price – in dollars, take the hint – for killing Pakistani soldiers. The foreign connection was, similarly, emphasised when, in 2011, the ISPR launched another drama series based on the operation in Swat, Faseel-e-Jaan Se Aagey.

It was only after the Taliban were defeated in Swat that the military regained some of its lost grip on the public’s imagination. Soon it was back on the offensive — narrative-wise, that is.

A self-professed “tribute to the immortals by the mortals”, Faseel-e-Jaan Se Aagey dramatised the true stories of army officials, civilians administrators and ordinary citizens who had stood up to the Taliban. Produced by a private company, Communication Research Strategies (CRS), many of its episodes were written by Zafar Meraj, a senior television writer. “I received 10 stories from the ISPR,” he tells the Herald about the process of finalising which stories to show.

One of the stories televised under the serial was Ma’arka-e-Chuprial. Among other things, it showed a Taliban commander inviting a mysterious person from across the border to operate the anti-aircraft gun that the Taliban had acquired. His identity as a Hindu was revealed at the end of the drama when, faced with certain death, he told the Taliban to cremate him instead of burying him.

In 2012, the ISPR collaborated with veteran actor-director Naeem Tahir to produce a serial called Samjhauta Express. As its name suggests, it was meant to “dispel the impression created by the first flash of the media news that Pakistan was behind the blasts [that had hit Samjhauta Express plying between India and Pakistan],” says Tahir in a conversation with the Herald. Its other objective, he adds, was to underscore the “genesis of terrorism and militancy in Indian society.” The serial was clearly a counter-offensive aimed at convincing the Pakistani public that their country was a target of India-inspired conspiracies.

The military’s media managers were thrilled when Waar, a feature film starring the popular film actor Shaan, opened to packed cinema halls in 2013. It could easily have been an ISPR production: it had an aggressively patriotic theme, with a former army officer as its protagonist and a seductress as an Indian agent who sponsors and promotes terrorists in Pakistan. Many in the media, indeed, alleged the funding for the film had come from the military but its makers vehemently denied that. They, however, acknowledged that they had produced The Glorious Resolve, almost simultaneously with Waar, for and with financial support from the ISPR.

Major General (retd) Athar Abbas, who headed the ISPR before Bajwa, tells the Herald that there was a proposal during his tenure to employ film as a propaganda tool. But, he says, the General Headquarters (GHQ) refused to allocate money when the ISPR asked for it in 2012.

After Raheel Sharif took over as the army chief in 2013, the ISPR presented the proposal to him again and he instantly approved it. Bajwa and his team approached Dr Hassan Waqas Rana, the writer of Waar, to produce the movie with a self-explanatory title Yalghaar (meaning ‘attack’ in English). The story of the film revolves around a commando operation to retrieve the Peochar Valley in Swat from the Taliban.

Rana tells the Herald that the film’s financing and making were both difficult propositions but the ISPR’s cooperation has helped him on both counts. “I could not have undertaken this 3.5 million-dollar project without the ISPR’s help,” he says.

While a large part of this massive amount of money required for the film is being provided by a private media house running a number of television channels, the ISPR has spent additional money to provide logistical support to the production team. “It would have been impossible for me to make this movie”, reiterates Rana, “without logistics, transportation and authenticity of script”, all ensured by the military.

Bajwa is eagerly awaiting the release of the film. In a tweet in July this year, he celebrated the release of Yalghaar’s first trailer and hailed the movie as a harbinger of the revival of the Pakistani film industry. More than that, he will be looking forward to its impact on the battle for hearts and minds that his department is so desperately trying to win.

This impression leads people to expect from the military everything that they cannot otherwise get or have.

Yet, as Amir Raza, a young writer who has a penned a television drama for the ISPR, points out, the military does not need to get directly involved in producing plays or films to create and promote a certain narrative. “Pakistani movie production houses are doing the ISPR’s job without the ISPR even having to spend a penny on it,” he says.

Raza cites the example of Border, a 2002 movie directed and produced by Iqbal Kashmiri, in which Shaan is shown as a patriotic solider who returns from a border post to his village to find cable television and Indian media products polluting the morals of the villagers. While a court in the movie hears an elopement case, he makes a dramatic entry into the courtroom and asks the judge to punish the cable network operators responsible for facilitating an Indian cultural invasion. “When I watched this movie in a cinema in Lahore,” says Raza, “I saw people clapping throughout the courtroom scene”.

Even in other mediums, the ISPR’s direct intervention is not really required. Most news bulletins and newspaper front pages in any case cover the statements and activities of the top military leadership, especially the COAS. On an almost daily basis, his engagements in different military and non-military tasks – ranging from visiting foreign capitals to inaugurating a charity cricket match and from chairing law and order meetings in Karachi to conferring with senior government leaders over the security situation in the country – are shown and reported about very prominently. When the military high command is not in the top headlines, military themes are.

In newspapers for August 31, 2015 alone, two front-page news reports were about India’s overt and covert aggression towards Pakistan. In one of them, Defence Minister Khawaja Asif warned India of unprecedented retaliation if it continued firing on Pakistani villagers across the international border in Punjab. In the other, Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif and COAS Raheel Sharif were reported to have provided the visiting American National Security Advisor Susan Rice the proof of Indian involvement in fomenting violence in Pakistan.

The same day’s daily Jang, the largest selling Urdu-language newspaper in Pakistan, carried a half-page advert on page two, celebrating the bravery of the soldiers who had lost their lives in different battles and had won the Nishan-e-Haider. The newspaper, and its sister publication in English, The News, had run similar ads throughout the month of August.

On Independence Day, many newspapers in Karachi, Lahore and Islamabad carried a full-page ad by the son of a late army captain. It showed COAS Raheel Sharif in his military uniform dominating the page — separated by a green swoosh above his cap, a sentence in Urdu read:“Only you are the pride of Pakistan”. The total cost of the ad could easily run into millions of rupees but there is no knowing who actually has financed it.

As the 50th anniversary of the September 1965 war with India drew closer, the ISPR launched another ad campaign, highlighting different aspects of that war and hailing it as a “victory”. A build-up for this, in fact, had started on August 14, when the military and paramilitary forces had arranged elaborate celebrations in different parts of the country. The very ostensible focus of these celebrations was on the military’s role in curtailing terrorism and ensuring law and order in such chaotic places as Karachi and Balochistan. The streets in many cities were lined with as many Pakistani flags as banners and posters praising the top military leadership, COAS Raheel Sharif and ISI chief Akhtar in particular.

An occasional poster could be seen eulogising Bajwa for his media management and clear-as-crystal statements on issues of national importance. After all, the ISPR under him has released five national songs this August alone — more than what all the public and private television channels and other media combined could manage.

A celebration of Pakistan’s popular culture – from truck art to chai stalls and from dhol playing to Sheedi dance – the accompanying video for this song shows Pakistan in all its ethnic, cultural and religious diversity. The lyrics are deceptively free of any ideological quotient. Religion, militarism, hyper and wounded nationalism are surprisingly missing from both the lyrics and the video. It is, indeed, an undiluted celebration of a young vibrant Pakistan, enjoying its mosaic identity.

The fact that the song was released two days before Independence Day on August 14, 2015, that it is written by a serving army officer, Major Imran Raza, and that it is produced by the ISPR is a clear reflection of the desire among the military’s media managers to stay ahead of the national narrative in any possible way they can. If the nation needs religion and patriotism for mobilisation, there should be an ISPR song to do just that; if people should be convinced that Pakistan’s troubles are the creation of the outsiders, there has to be either a film or a play to hit that message home; and if people across ethnic and religious divides seem to enjoy their common popular culture, then, of course, it becomes imperative to celebrate and promote that popular culture.

The problem with this ever-changing narrative is that, well, it changes too frequently and too fast – from religion, patriotism and militarism to religious and ethnic diversity and back, in the space of a single song.

In the second week of December 2012, two senior army officers – one from the ISPR and another from the ISI – sat in a meeting of the Central Board of Film Censors in Islamabad. The meeting was called to discuss whether Pakistan should allow the import of Indian films. “Not even a single scene or dialogue against the national interest could be allowed to show,” is how the army officers are said to have set the criterion for importing and showing of an Indian movie. A senior official, who was also among the discussants, tells the Herald that the principle was so sternly put forward that nobody dared asked them as to what constituted national interest and who had the mandate, and the wisdom, to define it.

Only a month prior to the meeting, the Pakistani government had banned the screening of Ek Tha Tiger, starring Salman Khan, because it showed a female ISI operative eloping with an Indian intelligence official. Since then, a number of Indian films have been banned because they are seen to include content repugnant to Pakistan’s national interests, the latest being Phantom which has kicked up an uproar among the Pakistani nationalist circles for portraying Pakistan and its intelligence agencies in a negative light. The movie has been banned by the Lahore High Court on a petition filed by Hafiz Saeed, an anti-India religious leader considered close to the security and intelligence agencies.

In the past, even Pakistani films had been banned for hurting the “national interest”. The most famous instance of this is the banning of Punjabi language film Maula Jatt, released in 1979. Senior film critic Ejaz Gul tells the Herald the reason behind banning the movie was its “anti-establishment” message. Such a message was deemed politically dangerous in the immediate aftermath of the military overthrow of Zuklfikar Ali Bhutto’s government. “Officials from the ISPR and the interior ministry were members of the censor committee that banned the movie,” says Gul. It was only after the producer obtained a stay order from the Lahore High Court against the ban that the movie could be shown in cinemas in Punjab and Sindh.

The desire and the need to control and calibrate the media products as per the dictates of “national interest” is even more evident in the films and plays being directly or indirectly sponsored by the military’s own media managers. Senior staffers at the CRS, which has produced a number of ISPR-supported television plays, say both the idea and story of each play they have produced came from the ISPR.

Even though the scripts are written by professional scriptwriters selected and hired by the CRS, their output is vetted, approved – and even changed if required – by the ISPR before shooting for the show starts. Once the shooting is complete, the draft play is again vetted by a board constituted by the ISPR and comprising officials from the army’s GHQ, Military Intelligence and the ISI. Their recommendations are included – and that is a must — before the final product is released for broadcast.

There can be nothing accidental or inadvertent about the carefully selected and strictly analysed scripts of these plays. All references, narratives, characters and messages are intended to be there for a certain reason. That raises some serious questions about those parts of the plays that purportedly make social and political commentary.

Consider the case of an ISPR produced drama serial, Jaan Hatheli Par. Its main objective is to highlight the military’s fight against a nationalist insurgency in Balochistan. When one of its lead characters riles against tribal chieftains in the play’s official promo, he is certainly making much more than just a statement against ethnic terrorism: “The tribal chief who cannot provide clean drinking water to his people has no use as a tribal chief,” he shouts angrily.

In the recent past, the makers and builders of the national image have kept their efforts abreast with the military’s objectives and challenges.

Similarly, in the play titled Ma’arka-e-Chuprial people complain to a soldier about the loot and plunder Pakistan has been subjected to. He advises them to fulfil their own responsibilities as he and his comrades in arms have been doing. It is because of the army’s alertness that millions of people in the country sleep peacefully every night, he tells them. The contrast is obvious. While others are looting and plundering the country and not doing their jobs properly, the military is the only institution selflessly performing its arduous duties so that people can have peaceful lives.

Apart from these oblique attempts at setting the national social and political agenda, the ISPR has recently tried doing so directly, too. It has produced a six-and-half-minutes-long collection of SOTs (sounds on tape) by leading Pakistanis which emphasise Jinnah’s vision of a liberal and progressive Pakistan — with Zia Mohyeddin’s narration in the background. “One man, one vision, one nation” is the title of the clip meant as a tribute to Jinnah, the man, the lawyer, the leader, the statesman. It stresses his political ideals of equality, justice and the rule of law.

Is providing all this political and ideological education to the nation within the ISPR’s mandate?

Ideally speaking, a national narrative has to come from the representative institutions and the civil society, says Syed Talat Hussain, a leading television talk-show host and political analyst. “Narrative-building should be the job of the parliament. To be more specific, it should be the job of the opposition and the government within the parliament,” he says.

Saeed Shafqat, a Lahore-based analyst and teacher of politics who has written extensively on civil-military relations in Pakistan, argues that the civilian institutions and civilian government are completely out of the picture as far as the setting of national narrative is concerned. This, he says, is mainly because of their ineptitutde and incompetence. “It seems they have nothing to say and nothing to do,” he adds. “The only institution that seems to be working is the army.”

This impression leads people to expect from the military everything that they cannot otherwise get or have. And many of them, therefore, are always happy to appeal to the military to take over power and put the country back on track. “Perfectly respectable people would come to me … and say, ‘You can save the situation’”, wrote Pakistan’s first military ruler General Ayub Khan in his book Friends Not Masters while describing the reasons for his takeover of the government in 1958. In an eerily similar way, portraits of COAS Raheel Sharif adorned huge billboards in all major cities in the run-up to Defence Day on September 6, 2015, carrying such loaded texts as, “Step up Raheel Sharif, we are with you”.

In contrast, Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif’s images were singularly missing from the public sphere. Even in television news bulletins and front pages of the newspapers, the coverage of the prime minister looked like an after-thought, an appendix to the main offerings of the day.

Shafqat, however, argues the civilian sloth could be the result of some hidden deal between the civilian authorities and the military establishment. There could be an understanding between the government and the army, he says; under this decidedly lopsided agreement, the army says “we will do everything” and the civilians agree and say “we will not do anything”.

Is the military then trying to steal all the limelight for itself, relegating the civilian institutions to a secondary status in a state apparatus where they look more like observers than active participants in the nation’s political life? Brian Cloughley, a defence expert who has studied South Asia for 30 years and authored two books, including A History of the Pakistan Army: War and Insurrections, does not agree. He believes the military in Pakistan has a “legitimate need” to project a countrywide narrative due to the situation it finds itself in while fighting the war against terrorism.

A senior ISPR official defends his department’s forays in setting the national narrative in fields which are not strictly the military’s domain in a similar fashion. For him, the country’s image and its security are one and the same thing. “When we talk about security, when we talk about defense, we have to take into account the overall image of the country,” he says in a background interview. “We, therefore, have to work to build a better image of the country.”

Siddiqi warns that such sweeping mandate to set everything right gives the military leadership a wrong type of confidence. “The generals, by and large, [become] too sure of their ability always to put right the mess created by the politicians,” he observes in the preface to his book, The Military in Pakistan: Image and Reality.

When Asrar launches into his part-Sufi, part-classical, part-pop rhapsody to sing this song released on August 14, 2015, the images of soldiers clad in different types of postmodern battle fatigues and in different fighting postures quickly change in an impressive montage on the screen. The viewer can be forgiven for being confused: Is it the country that the song is talking about or the military?

Siddiqi calls this mixing up of the country with the military as “prussianism”. “[The military’s] image grows apace, and presently reaches a point of predominance and power where it becomes an object of mass reverence or fear. A sort of prussianism is born to produce an army with a nation in place of a nation with an army. The national identity and interest is progressively subordinated to the growing power of the military image,” he writes in the preface to The Military in Pakistan: Image and Reality.

Commenting on a precursor to Asrar’s song, Siddiqi says in the book: “The face of the solider in his battle kit became the face of the nation and its most popular image.”

The mixing of the soldier with the nation could result in extremely naïve notions of military superiority and invincibility, especially in a state heavily dependent on foreign aid and technology to even equip its armed forces. Siddiqi quotes a funny, if not tragically self-delusional, incident.

Amid the popular euphoria and public ecstasy over the 1965 war, foreign journalists were invited to survey the opinion of the citizens of Lahore to gauge how motivated people were as the war raged on the nearby border with India. “A foreigner asked a Pakistani what implements of war Pakistan manufactured — tanks, guns, aeroplanes?,” Siddiqi narrates. “‘Nothing’ the Pakistani answered innocently. ‘What the hell do you produce then in this country to fight a war?’ ‘Taranas’ (songs), answered the Pakistani, just as naturally as before.”

— Additional reporting by Muhammad Badar Alam, Abid Hussain and Laila Husain

This was originally published in Herald's September 2015 issue. To read more, subscribe to Herald in print.