The confluence of commerce and culture, politics and gang war, crime and conflict, Lyari comes together at Aath Chowk. It starts falling apart as one moves away from it. The eight paths that lead to, or from, Aath Chowk, pass through eight places, monuments to eight defining moments in the turbulent history of Lyari.

Lea Market, February 2015

Located on the south-eastern edge of Lyari just off Napier Road, this is a commercial area like any other in the old part of Karachi — bustling but crumbling and untidy. On a spring day, it belies Lyari stereotypes: this bazaar in the ‘crime capital of Karachi’, the ‘mega-slum’ and the ‘most dangerous place’ in the city is abuzz with commercial activity.

A police patrol slowly moves through the area, a distant reminder that this is no ordinary terrain.

Housed mainly in a yellow sandstone British-era marketplace, marked by a clock tower, Lea Market has been the source of millions of rupees of extortion money every month, collected by the operatives of criminal gangs active in the area. It is also right next to Sarafa Bazaar – the largest jewellers' market in Karachi – which, in turn, is connected to many other markets and bazaars where money briskly changes hands — more often than not landing in the pocket of someone wielding a gun or operating a gang. All these commercial centres to the east of Lea Market are contested territory between warring gangs and their political patrons.

Lea Market flashed into the limelight on May 22, 2012.

Uzair Baloch, leader of the Baloch of Lyari, the area’s public do-gooder in chief, head of a gang, leader of the just outlawed Peoples Aman Committee, took out a public rally that day out of Lea Market. Having quit the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) a few months earlier, he invited the chief of the Sindhi nationalist Awami Tehreek, Ayaz Latif Palijo, to co-lead the rally with him.

The public purpose of the event was to convey a political message — all of Sindh belongs to all Sindhis; there should be no no-go areas anywhere. Titled the Mohabbat-e-Sindh rally – a rally borne out love for Sindh – its participants were ostensibly there to oppose demands for a separate Mohajir province. Its not-so-hidden agenda was to convey to the Muttahida Quami Movement (MQM) that all the commercial areas falling between Empress Market and Lea Market were an open playing field: anyone should be able to collect protection money here. Lyari’s infamous gang warfare was entering the scramble for bigger spoils.

As the participants of the rally stepped out of Lea Market, gunmen allegedly linked to the MQM opened indiscriminate fire from adjacent lanes. At least 12 people, most of them young men, lost their lives.

Jhatpat Market, March 2014

Some 500 metres from Aath Chowk, Jhatpat Market is a popular shopping spot for women. Disorderly and without a distinct architectural character, its shops, handcarts and makeshift stalls sell all types of clothes and accessories for women.

That March afternoon, the market was full of shoppers when it was rattled by a sudden boom of hand grenades, rocket propelled projectiles and gunfire. It was one of the countless clashes that Lyari has suffered over the last decade and a half among its myriad criminal gangs.

When the battle finally ended, it had taken the lives of 12 women and four children.

The residents of the area were enraged. They immediately brought out a protest demonstration and reached in front of the Karachi Press Club to make their shock, anger and grief known to the media and the government. Shouting slogans against the members and leaders of the two main gangs operating in Lyari – one headed by Uzair Baloch and the other by Baba Ladla – these protesters demanded what they called a ‘minus two’ formula.

It was after this protest that the security forces, comprising mainly paramilitary Rangers but also backed up by the police, started carrying out a search, arrest and kill operation in Lyari. “It was after the tragedy at Jhatpat Market that the Rangers made their presence felt in Lyari after more than five years,” says Ramzan Baloch, a former government official and a Lyari resident.

Bizenjo Chowk, August-September 2013

Named after the late Baloch nationalist leader Ghaus Bakhsh Bizenjo, this place marks the junction of Chakiwara road and Mewa Shah road. It was here, according to Elahi Bakhsh Baloch, a local social activist, that Lyari repeated the most persisting pattern of its deadly gang wars, which stretch well back into the 1960s.

It all started at a late-night football game.

As people were preparing their pre-dawn meal one day in Ramzan, a stadium next to Bizenjo Chowk was festively lit up. Two teams of Lyari youngsters were pitched against each other; they owed allegiance to the same patron — one was named as Baba Ladla-92 and the other Baba Ladla-99.

Noor Muhammad aka Baba Ladla was, indeed, the chief guest at the game. As was Javed Nagori, a PPP provincial minister elected from Lyari. As the winners were celebrating, everything suddenly went upside down. A huge explosion killed 11 people, including 16-year-old Abdul Basit, the captain of the winning team, and six of his teammates.

The police claim the explosion was carried out through a planted device and was meant to kill Ladla, who at that point was the enforcer-in-chief for Uzair Baloch’s criminal operations, and Nagori, hand-picked by Uzair Baloch to become a member of the Sindh Assembly. Ladla’s supporters allege the explosion was masterminded by Zafar Baloch, a former PPP office-bearer in Lyari who had been serving as the public and political face of Uzair Baloch-led Peoples Aman Committee.

Since the days of Dadal, Sheru and Kala Nag – the original founders of gangland Lyari in the 1960s – such infighting has been the staple of the area’s criminal lore. By the 1980s, Dadal and Sheru were fighting pitched battles with Kala Nag’s son. In the next phase of this saga of friendship, betrayal and death, Lal Muhammad – aka Lalu – and Babu were fighting it out among themselves for supremacy in Lyari’s underworld. By the early 1990s, Dadal’s son Abdul Rehman had joined the fray, becoming the leader of Lalu’s death squad.

In another re-enactment of the past, Lalu’s son Arshad Pappu became Rehman’s nemesis. When Rehman was killed in a police encounter in 2009, the leadership of his gang and the Peoples Aman Committee he had established fell in the hands of Uzair Baloch whose father, Faiz Mohammad Baloch, was kidnapped and brutally killed by Pappu in 2003.

Since Faiz Mohammad Baloch was closely related to Rehman, his murder resulted in pitched battles between his gang and the one headed by Pappu. Their deadly clashes continued over the next five years.

After the football match that ended in carnage, revenge was in Lyari’s air — once again. On September 18, 2013, unknown assailants gunned down Zafar Baloch, along with his guard, right at Bizenjo Chowk.

With Uzair Baloch having shifted abroad earlier that year, Ladla set out to bring the whole of Lyari under his control. This led to a fresh phase of the deadly gang war — leading to the death of hundreds of young men over the last 18 months, says one former government official living in Lyari.

Brohi Chowk, March 2013

This little known area close to the Lyari Expressway has been the site of perhaps the most gruesome murder ever committed in Lyari.

“Following the capture of Arshad Pappu [by Uzair Baloch’s men in March 2013], the population of Lyari was invited through the loudspeakers of local mosques to take part in his “punishment”. Pappu was then tied to a car, dragged naked, beheaded, dismembered and finally burnt. This gruesome performance culminated with young armed men … playing football with his severed head,” writes French scholar Laurent Gayer, in his recent book, Karachi: Ordered Disorder and the Struggle for the City.

When the rivalry between Pappu and Rehman first became public, the MQM reportedly started patronising Pappu to weaken Rehman and, thereby, loosen PPP’s political grip over Lyari, its last remaining stronghold in Karachi.

By 2008, clashes between the two groups had taken the lives of around 500 young men. With Pappu’s vicious murder, Uzair Baloch became the undisputed king of Lyari. He was so powerful at one point that he forced the PPP to award its election nominations only to individuals he had hand-picked for Lyari’s one National Assembly and two provincial assembly seats.

Uzair Baloch was named as the main culprit in the case registered for Pappu’s murder. Between April and July 2013, multiple police raids at his home in Lyari’s Singo Lane for his arrest remained unsuccessful. Even when he was holding meetings with residents of Lyari and lording over a jirga in his courtyard, law enforcement agencies were unable to lay a finger on him.

The law of unintended consequences, however, eventually caught up with him. Stung by his multiple betrayals and blatant blackmail, the PPP was unrelenting in its efforts to capture him after the party came back to power in Sindh in the summer of 2013. He had to run. Sometime last year, he was first spotted in Dubai where he was arrested and is undergoing hearings for extradition to Pakistan.

Back in Lyari, his former home turf – spread over Rexer Lane, Singo Lane, Bizenjo Chowk, Chakiwara and Shah Baig Lane – is now under the control of the Rangers. “We have set up checkpoints. We aim to cleanse the area of criminals in the next few weeks,” says a senior Rangers official without wanting to be named. “A further expansion in checkpoints will be made after March.”

The impact of the Rangers’ presence is noticeable.

The frequency of violent crime has come down; drug dealers too, are not operating in public view as they were in the past. Local residents acknowledge that incidents of firing have decreased. Yet, one of them, a journalist, complains that Rangers are targetting only specific areas. “It is evident that the Rangers are clearing out areas which were previously under [Uzair Baloch’s] control,” he says, without wanting to be named due to security threats.

The Rangers deny the allegation. “Our mandate is to break the backs of these criminal gangs,” says a senior Rangers official. “We carry out our operations without bias towards any particular gang.”

Since March 2014, the Rangers have conducted more than 600 raids in Lyari and have nabbed 153 gangsters and 246 extortionists. The official claims only those criminals and suspects were killed in encounters who put up resistance and shot back at the raiding parties. “Everyone who died in encounter was a criminal,” he says. The rest, he claims, are undergoing various stages of their trials.

Cheel Chowk, April-May 2012

A big metallic kite, in full flight, sits atop a round yellow stone-and-concrete structure in the middle of this large road junction in the northern part of Lyari. Surrounded by unplanned residential and commercial buildings, it is a major gateway into the Baloch-dominated parts of Lyari, extending from the west of Lea Market to the Lyari River. The Chowk saw some extremely intense battles between law enforcement personnel and gangsters in the early part of 2012.

Uzair Baloch at the time had decided to take on his erstwhile benefactor — the PPP.

On April 26, 2012, Malik Mohammad Khan, a long-time PPP activist and a former naib nazim of Lyari Town, gathered the party’s supporters together for a protest demonstration against the conviction of the then prime minister Yousuf Raza Gilani for contempt of court. Early in the afternoon, the protesters reached Aath Chowk where armed men riding motorcycles tried to disperse them, media reports say. Some of the armed men came right in front of Khan who was leading the protesters. He was pushed into a corner and shot dead.

It was a declaration of autonomy and rebellion, a blood-soaked warning message to the PPP that its efforts to disband the Peoples Aman Committee were to face as stiff a resistance as anyone would expected from a well-resourced, well-entrenched Lyari gang.

Enraged, the government ordered an immediate crackdown against Uzair Baloch and his men. A day after Khan’s killing, the police raided Uzair Baloch’s home. They could not find him.

The provincial government then sent in “nearly 3000 police personnel in bulletproof vests [and in] armoured personnel carriers,” reported the Herald in its June 2012 cover story. For the next week or so, this huge law enforcement contingent, headed by dreaded police official Chaudhry Aslam, remained mired in street battles with gun-wielding gangsters on one hand and stone-throwing young protesters on the other. “Every time they tried to step out of their armoured personnel carriers to capture the pickets manned by gunmen, the police had to beat a hasty retreat due to heavy gunfire,” reported the Herald.

By the time the operation was called off on May 4, 2012, five policemen had lost their lives along with many civilians caught in the crossfire.

Addressing a press conference later, Aslam claimed the police campaign was not an “operation” but a raid, conducted in order to flush out militants belonging to the Baloch Liberation Army (BLA). His claims were impossible to verify.

Even though no evidence exists to link Uzair Baloch to the BLA, he was definitely branching out politically at the time. He established contacts with the Pakistan Muslim League–Nawaz, which was eager to make electoral inroads into Lyari, and Sindhi nationalist parties, particularly Ayaz Latif Palijo’s Awami Tehreek which believed its anti-PPP politics would gain traction among the disgruntled Sindhi and Baloch residents of Lyari. They planned a series of what they called Mohabbat-e-Sindh events.

Uzair Baloch also made an attempt to be on the right side of the military establishment which, in early 2012, was deeply displeased with the PPP and its government over the so-called Memo scandal.

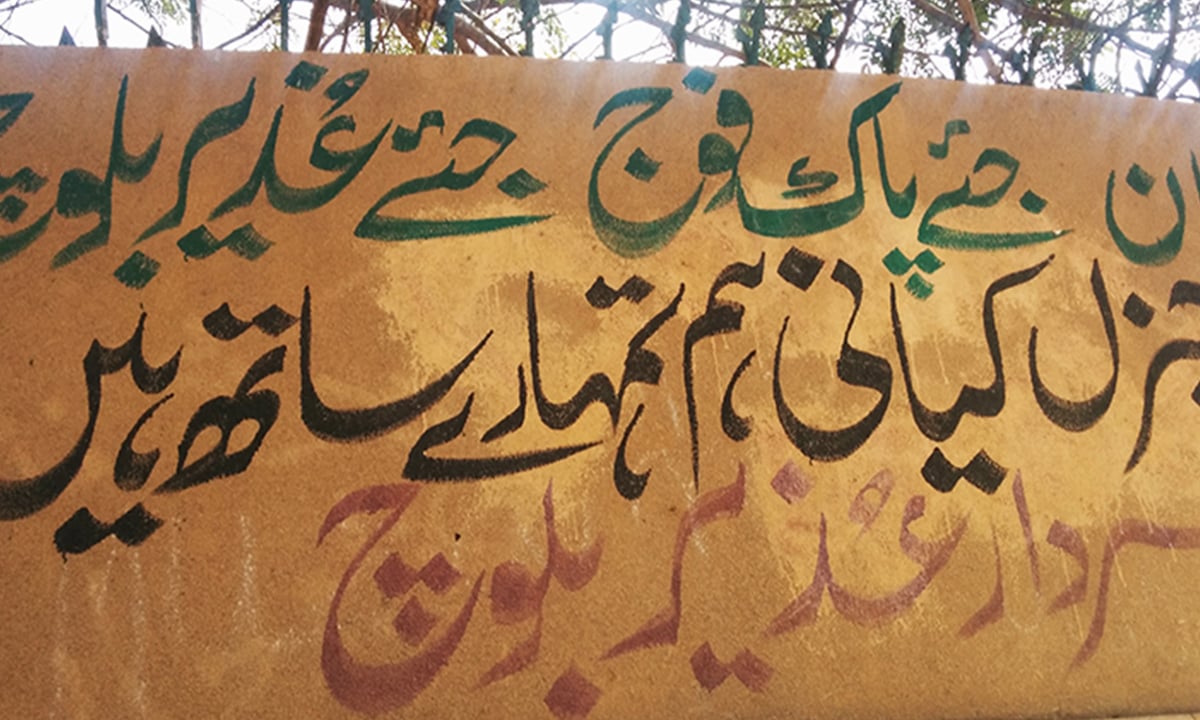

Graffiti supporting the paramilitary Rangers, Pakistan Army and the army chief was suddenly everywhere in gangland Lyari. He also offered to hand himself over to the Rangers, provided that the PPP government stayed out of it.

“There were marches, graffiti and banners supporting the Pakistan Army,” says a journalist, associated with Lyari-based magazine Sada-e-Lyari. Uzair Baloch’s pictures adorned all that ‘publicity material’.

The security establishment’s views on Lyari’s newfound love affair with it were impossible to know but the Rangers, mysteriously, decided to stay out of the April-May 2012 police operation in the neighbourhood. They never explained why.

Aman Park, October 2011

A small park in Idu Lane once housed the central office of the Peoples Aman Committee. It wears a totally deserted look now.

Rehman, by then known as Rehman Dakait, had founded the Peoples Aman Committee in 2008, with unconcealed political ambitions. In Dr Zulfiqar Mirza, Sindh’s home minister at the time, he found an eager collaborator.

Mirza wanted to tackle the MQM-based violence in the city through strong-arm tactics after failing to do so through law enforcement agencies. In multiple media interviews given since 2011, he admits to having issued thousands of arms licences to people in Lyari as well as other parts of Karachi so that they could “protect themselves from those planning to take over their space”.

Lyari gangsters did not need those licensed guns, nor were they interested in self-defence. They had guns aplenty and their aim was to extend their criminal operations for extortion, kidnapping for ransom and drug dealing beyond Lyari.

As Rehman had already consolidated his grip over most criminal activities within Lyari, he thought he was now powerful enough to expand and extend his network. Mirza’s offer to him to join hands against the MQM could not have come at a more opportune time.

The results of their cooperation were immediately obvious. The MQM saw its monopoly over violence severely challenged, and eroded, especially in older parts of Karachi such as Kharadar, Mithadar, and Saddar but also as far as Malir and Landhi.

The potent cocktail of criminality, legitimised by politics and ethnic hatred, that flowed from this transformation of conflict scarred Lyari — particularly its young residents. The first and foremost visible impact was that Baloch youngsters from Lyari were socially ostracised; they were usually seen as gangsters in non-Baloch areas, and more often than not were falling victim to ethnicity-driven targeted killing. With most of the Karachi-based media partial towards the Urdu-speaking community, preconceived notions about the Baloch youth and Lyari residents all being criminals produced a mangled narrative which traumatised these sections of Karachi’s population in more ways than one.

“The young Baloch men experienced spatial restrictions due to the presence of a variety of threats both inside and outside their locality. These young men are both the subjects and objects of fear in a context in which male Baloch bodies have come to be framed as threatening by the state, rival political parties and the media,” writes Dr Nida Kirmani in her essay titled City of Fear: Everyday Experience of Insecurity in Lyari.

In one case, a 36-year-old college teacher from Lyari faced problems opening a bank account and getting a credit card because the bank felt he was a “credit risk”. In another instance, a resident of Khadda Market in Lyari registered his son’s birth in Saddar Town, to prevent him from being ridiculed or discriminated against for being a Lyari resident.

Even within Lyari, the neighbourhood was divided between a Baloch-dominated central area, where the Peoples Aman Committee had complete control, and non-Baloch areas on the periphery where the MQM-backed gangsters were operating.

The clashes between the two sides were frequent – and deadly – and were fought from behind heavily fortified border streets.

People living in one part of Lyari could not visit their relatives living in another part. “There was a time when we couldn’t even bury our dead in Mewashah graveyard because it too was taken over by a gang. They would not let people from a rival gang’s territory bury their dead there,” says a journalist working with with Sada-e-Lyari.

Lyari’s gangsters had become too big and too powerful to control. The provincial government had to do something — and urgently. After two years of letting the Peoples Aman Committee operate as its armed wing in and around Lyari, the Sindh government decided to ban the organisation in October 2011.

Chakiwara Road, 2008

Running from east to west across Lyari, this road bisects a number of Baloch-dominated neighbourhoods in the area. Between 2003 and 2008, gangs headed by Rehman and Pappu had divided these neighbourhoods virtually street by street.

As their clashes raged, residents would be confined to their homes for weeks, sometimes managing to move around through holes in the walls — passages that linked one house to the next, one street to the other.

In July 2008, the newly installed PPP government in Sindh decided to launch an “integrated operation” in Lyari. It involved 700-strong police force with a similar number of Rangers personnel. The operation was successful. It ended the gang war in most parts of Lyari — for a brief period of time, that is.

It did not finish the gangs and the gangsters, though.

The gangsters led by Pappu and his lieutenant Ghaffar Zikri were major losers in the operation. They lost a huge number of men and had to relinquish control of most parts of Lyari. Managing to escape the onslaught of law-enforcement agencies, Rehman saved his men and ammunition and was right there to assert his control over large tracts of Lyari as the police and the Rangers retreated to their headquarters.

The same year, the PPP put a political seal of approval on his criminal dominance by letting him found the Peoples Aman Committee.

Rexer Lane, circa 1974

Rehman was born in this non-descript residential area dotted by multistorey residential buildings and narrow, winding streets. He stabbed someone at the age of thirteen. By 1991, he was a known assassin operating on the behalf of a famous gangster — Lal Muhammad alias Lalu.

Thus was born the myth of Rehman Dakait, the legendary gangster of Lyari.

Sometime in the mid-1990s, he killed his own mother. Some say he did so because she was having an affair with Lalu’s opponent, Babu; others say it was an accident. Whatever the truth, this only added to his criminal mystique, writes Gayer.

Between 1996 and 2006, Rehman managed to escape from the custody of law-enforcement authorities more than once. Only a daredevil and wily man like him could do that.

Lyari was now a gangland working like the unfolding script of a Bollywood mafia movie, with a mythical and charismatic don at the helm. Generous to friends, mean to foes, he robbed the rich and fed the poor. No urban legend in Lyari, or for that matter in Karachi, is bigger than his.

People have tried to explain the gangster culture Rehman inspired. “There is an entire subculture that is very charming for teenagers who want to join the gangs,” says a Khadda Market resident who has observed the gangs from close quarters. “They get a stipend from the boss; they get a new bike, a gun. They have their own set of codes as well as a particular dress code such as six-pocket cargo pants and chequered shirts. It is the glamour of the mafia which sucks them in,” he continues.

On October 18, 2007, Rehman escorted Benazir Bhutto to safety when her caravan was hit by a massive bomb blast at Karachi’s Karsaz area. Rehman Dakait the gangster was transformed that day into Sardar Abdul Rehman Baloch, the brave political activist of Lyari who could do anything to protect the PPP leader.

A year later, he set up the Peoples Aman Committee.

In August 2009, he was killed in what is widely believed to be a stage-managed encounter with Chaudhry Aslam. “I have never staged fake encounters in my career,” Aslam told a newspaper interviewer later that month.

By killing Rehman, he got a new sobriquet among the residents of Lyari: encounter specialist. “I have no idea why people in Lyari call me ‘encounter specialist’ even though most of the criminals I have arrested are alive and in prison,” he insisted.

Aslam himself died in an ambush allegedly carried out by the Taliban in January 2014.

On an early March day, Aath Chowk is as calm as any place in Lyari is ever expected to be. Few vehicles ply on roads around it; human presence is thin. Yet, the place has all the signs of having been under siege and contestation for a very long time.

Heavily armed Rangers personnel peep through sandbags securing their checkpoints; their colleagues patrol the area on motorcycles. A tall rectangular marble monument marking the Chowk is half hidden behind a few PPP flags; graffiti praising the outlawed Peoples Aman Committee sitting cheek by jowl with them. Slogans praising Baloch separatists and Akbar Bugti as a martyr have also appeared. Across the road from the monument, the façade of a dilapidated two-storey building is covered with words scribbled in hasty handwriting — they are in praise of Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif and list his local supporters.

These disparate symbols all have an uneasy but peaceful coexistence at Aath Chowk. Life in Lyari seems to have picked up its shattered pieces and come together again — for now, at least.

It may fall apart yet again.

The tense calm at Aath Chowk permeates the whole of Lyari — its eerily tenuous existence trembling in trepidation, fearing the return of violence. A 60-year old resident of Rexer Lane complains to the Herald about the high-handed attitude of the paramilitary forces. “They don’t even care about the old and people with disabilities. They treat us like scum,” he says. Also sceptical about the outcome of the operation, he says it is worrying how “the operation has lasted for more than a year and nobody has questioned when will it end.”

Rangers officials say they are not working in haste. Prime Minister Sharif has promised to restore peace in Karachi by 2018, says one of them. “That is our deadline.”

Will the impact of the operation last or will Lyari once again descend into chaos? In his paper The Gangs of Lyari: From Criminal Brokerage to Political Patronage, Gayer writes: “At this point, the terrain is ripe for a renegotiation of the contract between political patrons and their criminal protégés. The success of this renegotiation is however conditioned to the goodwill of law-enforcement agencies, which are the only ones that can translate these ambitions into acts by dismantling the unofficial power structures set up by these criminals.”

This article was originally published in Herald's March 2015 issue. Subscribe to Herald in print.

The writer was a staffer at the Herald.