How a fixed gaze at the Muslim 'Other' helps political parties in India

Yesterday night, I received a call from my sister. In a rushed voice, she said, “My eight-year-old son is being pestered by his friend at school who keeps asking him if he believes in his god.”

Born to a Christian father and Hindu mother, he refused to engage questions about whether he believes in someone else’s God. However, the episode later took a violent turn when his lunch box was thrashed around by his friend and he was ridiculed for belonging to a certain faith.

“You must go to the school tomorrow and report this to the principal,” I told my sister with a sense of helplessness and rage, all at once. For a moment I wanted to disbelieve the fact that it was possible for one to possess such an acute and stark sense of identity at such young age

The very next moment, I turned to my friend and enquired as to whether he ever faced such a situation. He replied saying it was worse if not as bad.

My friend, who is currently pursuing a PhD in Sociology at IIT Delhi, recalled an incident when, in response to a complaint against a young Muslim boy, his teacher publicly humiliated him and said, “Boys like you later become terrorists.”

The boy was later made to leave the school by his parents.

He also recollected how during his childhood, he would be seen as an object of both curiosity and disgust. His friends would often ask him about circumcision rituals, if he ate beef and whether he supported Pakistan.

“Of course, all this happened in a mood of banter, but it sticks with you!” he said.

In 2002, the ripples from the Gujarat violence reached Patna. The very same friends now exchanged playful remarks about how they would target each other in a riot.

“Nothing happened! But it sticks around!” he repeated.

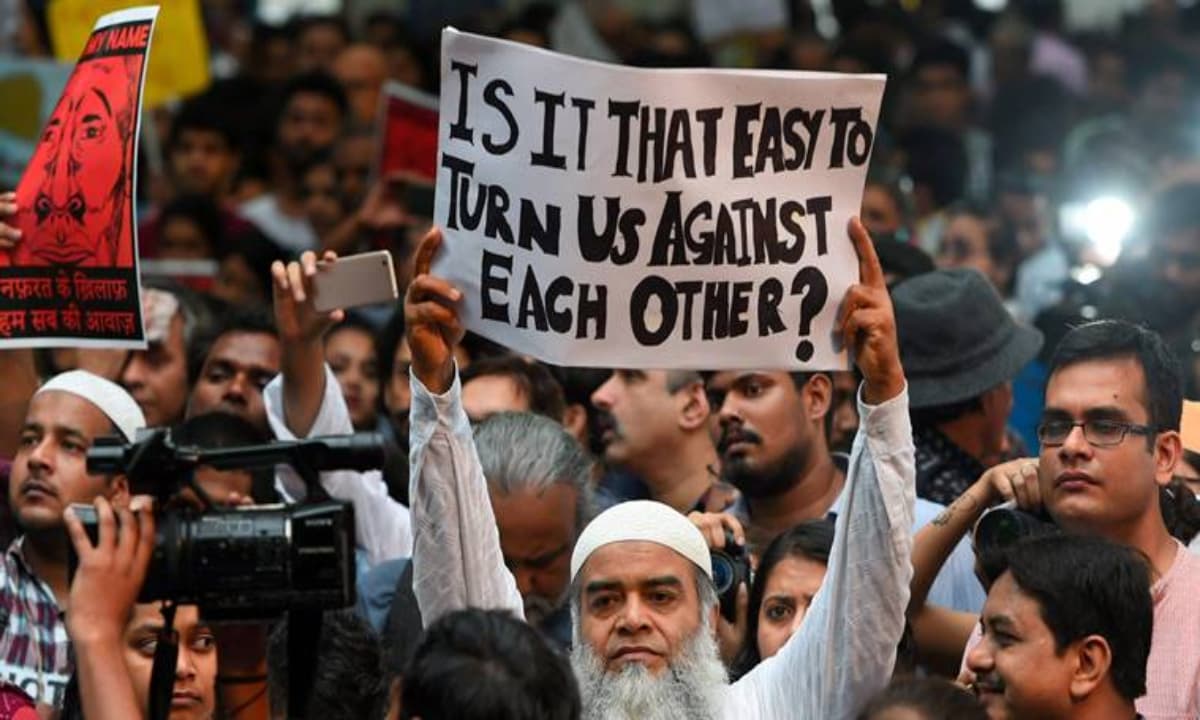

Escalation of communal rhetoric

A few days back, Shaukat Ali, an elderly man was thrashed and heckled by a vigilante mob in Assam. He was attacked not for being poor, or for doing something wrong, but because of his identity as a Muslim. Communal attacks in contemporary India are part of a new discourse where attacks are seen by everyone on their screens. Attacks take place at an intimate level where one is very efficiently conveyed the risk that their identity carries.

It is not simply a process through which Amit Shah, the president of the BJP, declares the official disenfranchisement of Bangladeshi Muslim migrants; it is also a process through which the Hindu majoritarian state produces and encourages anxiety and hostility towards the Muslims of the country.

The anxiety is not necessarily over the question of class, or a case of discrimination; more than that it renders a certain community as the ‘other’. This otherisation is a dehumanising process. It is a process through which self imagines the other as weak and powerless.

Recently, during the launch of Congress manifesto Rahul Gandhi exclaimed that “all were Hindu.” Instead of asserting and accepting differences, he purported to claim that the Hindu identity was national and universal. While his politics may claim to be different from that of Hindu majoritarian values, this time, strangely, the presence of other communities escaped his imagination.

This absence can also be gleaned from the fact that Ghulam Nabi Azad, an experienced Muslim leader from Congress, in an address to the alumni of Aligarh Muslim University rued the fact that Muslim figures have no visible presence in Congress’s campaign. He suggested that his own party leaders have stopped calling him for campaigns because they fear its impact on voters.

Intellectuals like Meghnad Desai and Kancha Ilaiah in their columns have also alluded to a certain tilt within the Congress towards proving its Hindu credentials (a brilliant example is Shashi Tharoor’s book Why I am a Hindu).

Desai even goes further and questions Congress’s use of acronyms such as NYAY – a scheme which promises to give Rs. 72000 yearly to every poor in the country. With its Sanskritised Hindi name that can capture people’s attention, to Desai, this appears less to be a counter and more an imitation of Modi’s style of politics.

The difference between BJP’s Hindutva and Congress’s Hinduism seems to be losing its ground. While the BJP, in order to assert the idea of a strong Hindu rashtra, represents the Muslim as a vulnerable figure like Shaukat Ali who can be excluded, humiliated and violated in broad daylight, Congress decides to altogether invisibilise them to present a truer Hindu self.

Invisibilisation of minorities

The invisibilisation of the community goes hand in hand with a call for the liberal idea of fraternity. This idea of fraternity, on the other hand, takes a more pronounced form in BJP which attempts to create a sense of superiority among Hindus (including working class and different caste groups) through a shared feeling of communalism against the Muslim other.

Like two bulls locked in each other’s horn, the worldview of BJP and Congress remains confined to a majority-minority relationship. The minority in the scheme of their dominant ideology is always the Muslim community in the country. The multiplicity of differences over region, language, caste and gender do not find any significant place in their idea of the national whole.

Had it mattered, the Hindu Brahmins with 5% of the total population would have ranked first in the minority list. Since this is not the case – as it would lay bare how power works in India – a fixed gaze at the Muslim ‘other’ and use of Muslims as a monolithic category helps both the BJP and the Congress keep their politics running without end.

Can we then think of going beyond the strategy of mere survival as a nation? Can we imagine a politics, an alternative politics, which recognises difference as a precondition for ‘national unity’? A politics based on the idea of recognition and representation?

In the existing political climate and the logic in which these two major national parties and their ideologies seem to be working, these questions remain far-fetched and very distant as of now.

The writer is a research assistant in the visual studies department at School of Arts and Aesthetics, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi.

The article was originally published in The Wire.