Back when it was formed in 1967, the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) quickly grew to become a viable alternative to established political parties that were increasingly viewed as part of a problematic status quo presided over by General Ayub Khan. With its charismatic leader and its message of radical social and economic change, the party would go on to bag a majority of seats in West Pakistan in the 1970 elections after winning over the support of key constituencies such as labour, peasants, students and urban professionals.

Yet, for all the rhetoric that surrounded its victory, it quickly became evident that PPP in power was a different beast from the party that had campaigned against inequality and oppression. Starry-eyed socialists and other progressive activists who had formed the core of its leadership in its formative years were quickly sidelined once it formed its government in the aftermath of the traumatic loss of East Pakistan in 1971. Many eventually left the party, complaining that it had lost its way and become beholden to the very interests it had sought to oppose.

PPP’s transformation from a party of change to one upholding the status quo should not have been entirely unexpected. Despite its indisputable popularity, the party was, at least partially, reliant on established landed politicians to win votes in Punjab and Sindh and this dependency only increased over time. Understandably enough, their electoral indispensability provided those politicians with considerable influence over questions of policy. In the grand scheme of things, vote-getters inevitably proved to be more important than ideologues sitting outside the Parliament.

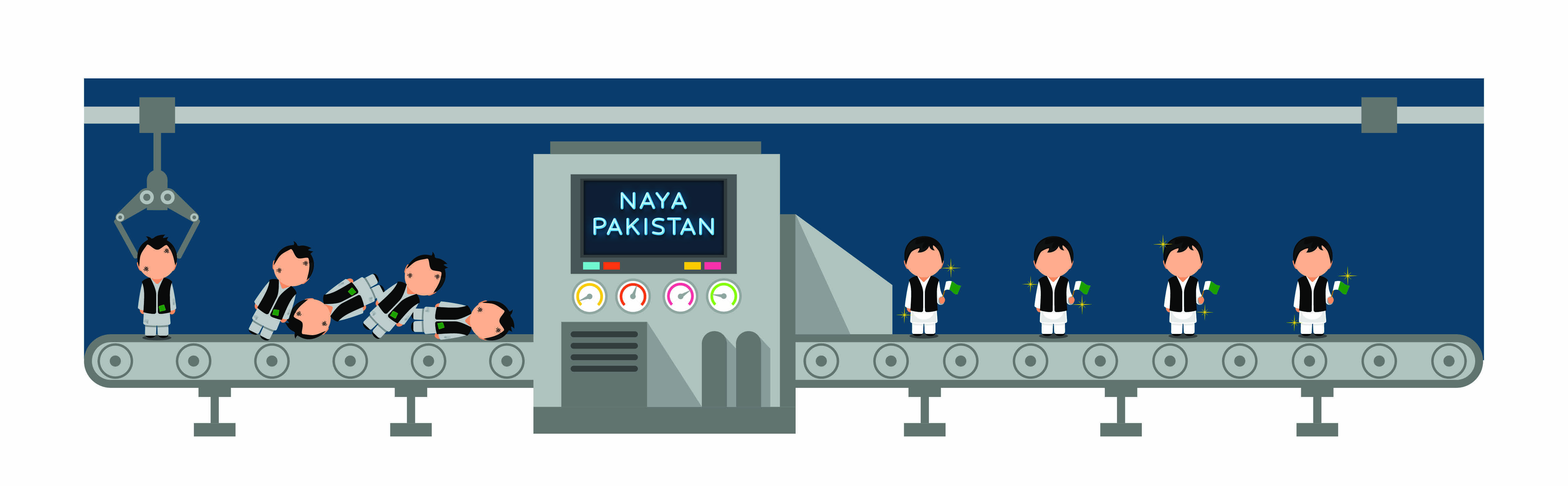

As the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) begins its tenure in government after winning the 2018 elections, it is easy to see some parallels with the events of the 1970s. While PTI is no PPP and Imran Khan is no Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, what is common between the two parties and their leaders is their seemingly inevitable capitulation to political reality, with slogans of hope and change giving way to accepting the need to compromise in the quest to win votes.

There has been a lot of debate on PTI’s reliance on electables – constituency politicians who have the ability to win their seats regardless of party associations – to secure victory in the 2018 polls. There has been, in fact, a long-standing split within the party between the electables, almost all of whom have been inducted into PTI over the last half a decade, and a so-called ‘ideological’ wing comprised of an older cadre of leaders and activists who have been associated with the party since its inception in 1996.

Those PTI leaders who supported the electable route to government have always argued that fielding established politicians as candidates, even when they have questionable reputations and shifting loyalties, is a necessary evil in an electoral system that favours influence over ideology. Its critics have always pointed out that systemic change can hardly be expected from those whose politics has thrived on maintaining the status quo.

If one looks at the composition of Prime Minister Imran Khan’s cabinet, there are plenty of reasons to share the scepticism of these critics. Of its 16 members (excluding five non-elected advisers), only three (Asad Umar, Shireen Mazari and Aamir Kiyani) did not hold ministerial positions either under General Pervez Musharraf (2002-07) or during PPP’s fourth government (2008-13).

What this means is that the vast majority of the cabinet’s members were aligned with other political entities at different points in the past, with some – such as Khusro Bakhtiar, minister for water resources, planning, development and reforms – having defected to PTI from the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PMLN) as late as May 2018. Six other members of the cabinet are from PTI’s coalition partners, arguably a disproportionately large number given the relatively small presence of these partners in the Parliament.

Contrary to what many core PTI supporters might have liked to see, cabinet portfolios are rarely awarded based on expertise. This is mainly because the actual task of formulating and implementing policy is usually not the responsibility of a minister. It is, instead, handled by the bureaucracy and experts staffing government departments. While it obviously does not hurt to have ministers who have a good grasp of their ministry’s remit, or who have experience relevant to their posts, much of their work is to provide leadership to officials working under them and to oversee implementation of the government’s agenda.

As such, in a context where ministers do not necessarily require subject-specific skills, what is the selection criteria that is used when forming a cabinet?

Around the world, not just in Pakistan, ministerial positions are often part of a broader system of reward and patronage used to cement alliances, repay loyalty and influence political environment. In this sense, Imran Khan’s choices are predictably pedestrian.

It is not surprising to find people like Sheikh Rasheed Ahmad (minister for railways), Fehmida Mirza (minister for inter-provincial coordination) and Ghulam Sarwar Khan (minister for petroleum) being rewarded for their defection to/support for PTI just as the appointment of Shah Mehmood Qureshi (minister for foreign affairs), Fawad Chaudhry (minister for information and broadcasting) and Shafqat Mehmood (minister for education) makes sense given the loyalty they have shown towards Imran Khan since joining his party and the central role they have played in PTI’s long campaign to outsmart its main rival, PMLN, before, during and even after the elections.

In rewarding opportunism and loyalty through cabinet appointments, Imran Khan is not very different from his predecessors. And if the past is going to be reflected in the future in a similar fashion, there is no reason to believe that his cabinet will not grow in the years ahead even though its current size is much smaller than the two that preceded it.

The same logic that seems to have underpinned cabinet appointments also appears to inform other appointments Imran Khan is making. While the new chief minister of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Mehmood Khan is a relatively new entrant to politics, his family has been associated with PPP in the past. He also served as a provincial minister under PTI’s previous government in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa with no obvious distinction.

Another case in point is the selection of Sardar Usman Buzdar as chief minister of Punjab. While Imran Khan announced his name as a radical move to bring an unknown politician from a backward part of the province to power, Buzdar’s father is a tribal chieftain who has remained a member of the Punjab Assembly in the past. He himself was elected as tehsil nazim from Taunsa, his native area, during the Musharraf regime and has remained in different parties including PMLN. It is equally important to note that he has faced allegations of corruption, and reportedly even of complicity in murder, in the past.

His appointment, therefore, may have more to do with his strategic value as a politician from south Punjab, an area that PTI would like to turn into one of its core constituencies in the future. His selection may also be because of his reported closeness to Jehangir Tareen, one of Imran Khan’s most trusted aides, rather than due to any specific acumen he may have for running Pakistan’s largest province. Similarly, Chaudhry Pervez Elahi’s elevation as the Punjab Assembly speaker, Asad Qaiser’s election as the National Assembly speaker and Chaudhry Muhammad Sarwar’s reappointment as governor of Punjab all smack of rewards being offered for continued political support in the case of the former and unstinted loyalty in the case of the latter two.

Another area in which Imran Khan and PTI have not really differed from their predecessors is the gender balance of the cabinet. With only three female members, the federal cabinet has an extremely skewed gender ratio. The nomination of yet more men for other posts, such as governorships and the presidency, means that PTI has missed the opportunity to have more women in high offices. Similarly, there is no representation of religious minorities in any of the high offices of the state and government, and the cabinet continues to remain a bastion of wealth and privilege with virtually all of the ministers drawn from among the political and economic elite of the country.

How the new ministers will perform in the months and years ahead remains to be seen but their past records in government, their political, economic and social backgrounds, and the motives underpinning their appointments do not inspire much confidence. For now, PTI’s Naya Pakistan does not seem very different from what it is replacing.

The writer is an assistant professor of political science at the Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS)

This article was published in the Herald's September 2018 issue. To read more subscribe to the Herald in print.