In many ways, Francis Robinson’s book is as much a summation of the life of its protagonist as it is of its author’s lifelong association with the study of Muslims in the Indian subcontinent. Renowned for his pioneering research on Islam and politics in British India, Robinson has produced works that deepen the understanding of the notion of modernity and the ways in which it has shaped individual and collective Muslim lives in this part of the world. Jamal Mian: The Life of Maulana Jamaluddin Abdul Wahab of Farangi Mahall, 1919-2012, in the same vein, charts the experience of modernised Muslim lives in colonial India and the transformation they have gone through due to Partition’s upheavals.

Jamal Mian is known primarily as the scion of a distinguished North Indian Muslim family. His story, as narrated by Robinson, is not the story of an individual; it is the intellectual biography of an era. The author is ideally suited to tell it, not just because of his scholarship on South Asian Islam but also due to the fact that he had a personal association with Jamal Mian and enjoyed unfettered access to his vast trove of private papers, including a journal maintained for years.

Robinson portrays his subject as an embodiment of Islamic scholarship’s centuries-old tradition to which Jamal Mian’s family contributed immensely. Those who are accustomed to hearing the names of such Sunni groups as Deobandis and Barelvis might not have heard the name of his ancestors – the ulema of Farangi Mahall – but they served as the most well-known purveyors of Islamic learning in North India for more than 300 years.

They traced their origin to one Jalaluddin who came to India as part of Shahabuddin Ghori’s lashkars in the 12th century. He settled near Delhi where he also founded a khanqah. His successors later moved to Awadh where one of them, Mulla Hafiz, received a revenue-free grant of land during the Mughal emperor Akbar’s reign. Local land owners so resented the favours bestowed upon his family by successive Mughal kings that they ended up killing Mulla Hafiz’s great grandson Mulla Qutbuddin. The detailed account of this gory incident was duly recorded and sent to Emperor Aurangzeb, who allotted Qutbuddin’s son even more property comprising the sequestered estate of a European indigo merchant of Lucknow. This property included a mansion – named Frank’s Palace – that came to be known as Farangi Mahall.

Robinson credits the Farangi Mahalli ulema for patronising the study of ma’qulat or rational sciences – such as philosophy, logic and mathematics – along with mankulat or religious texts. Their greatest contribution has been Dars-i-Nizami, a curriculum still followed in Sunni madrasas in Afghanistan, Pakistan and India. Initially devised by Qutbuddin, it is named after his son Mulla Nizamuddin who gave it a definitive form. He not only introduced the latest works on logic and philosophy in the syllabus but also adopted a new pedagogical technique that exposed students to the most difficult texts in each discipline. Once a student learned, understood and mastered those texts, Nizamuddin argued, the rest of the instruction would follow easily. Robinson attributes the success and popularity of this curriculum to its emphasis on ma’qulat which “formed good minds and good judgment for the business of government”.

What further distinguished Farangi Mahallis from the rest of Sunni Hanafi scholars in India was their deep attachment to Sufi silsilas (orders) and Sufi shrines. One, however, may argue that links between religious scholars and Sufis were common in precolonial India, though their continuity after the British takeover looked like an anomaly, especially given that calls for a more ‘sanitised’ version of Sufi beliefs and practices were quite frequent at the time, as were debates and sectarian splits on the issue of taqlid (the notion of following one of the four Sunni schools of jurisprudence or fiqh).

Most pro-taqlid Sunnis – such as Deobandis and Barelvis – are Hanafis like Farangi Mahallis but they have been increasingly uncomfortable with many syncretic South Asian Sufi practices embedded in the Subcontinent’s indigenous culture that accords shrines a place of distinction in a community’s religious and social life. To use the words of Amjad Ali Shakir, a historian of the Congress-affiliated, anti-colonial ulema, Deobandis and Barelvis (the former more so than the latter) were Hanafis in their maslak (religious doctrine) but not in their mizaj (temperament). They followed the fiqh of Imam Abu Hanifa but did not share his acceptance of diverse religious practices. Farangi Mahallis, on the other hand, were Hanafis by maslak as well as by mizaj.

They were linked to the Chishti Sufi order, in particular to Shah Muhibullah (1587-1648). He was a devotee of Abu Said Gangohi, the grandson of Abdul Quddus Gangohi who was known for popularising Andalusian Sunni mystic Ibn Arabi’s writings in India. Farangi Mahallis also developed links with the Qadiri order through Shah Abdul Razzaq (1636-1724) who was based in Bansa, a town in Bara Banki district of Awadh region. Their affiliation with the custodians of his dargah continued late into the British period. When Farangi Mahallis wanted to relaunch their family madrasa in 1905, they invited the sajjada nishin (holder of the sacred seat) of Bansa to inaugurate it.

Farangi Mahall’s significance as a seat of learning suffered many setbacks from the middle of the 18th century onwards. Firstly, its administrators had to contend with the aggressive Shia regime of Awadh that forced Mulla Nizamuddin’s son, Maulana Abdul Ali Baharul Ulum, to leave Lucknow in the 1750s. Secondly, the emergence of madrasa networks in towns across North India during the second half of the 19th century dented Farangi Mahall’s distinctive status as a religious school. In 1866, for example, Maulana Qasim Nanotvi and Rashid Ahmad Gangohi founded a madrasa at Deoband that, capitalising on the print revolution of the age, soon spread its fame and message to all corners of British India — even beyond to places such as Afghanistan.

Robinson completely overlooks a key question here: what explained the phenomenal success of Deoband at the expense of other madrasas including the one at Farangi Mahall? Only briefly does he mention Farangi Mahall’s competition with another madrasa, the Nadvatul Ulama in Lucknow, and the disagreements the two had over curriculum and methods of instruction.

Farangi Mahall’s decline as a madrasa, however, did not diminish the social status of its resident family. Jamal Mian’s father, Abdul Bari, took advantage of this social capital to find a central place for himself in Indian politics, especially at the outset of World War I and during the Khilafat Movement that followed. It was during this period that Jamal Mian was born in December 1919 on a day that, according to the Islamic calendar, corresponded with the 12th of Rabiul Awwal, the birth anniversary of the Prophet of Islam (may peace be upon him).

Robinson provides an intimate account of the social environment in which Jamal Mian was brought up, including a detailed description of his family’s residence and its adjoining neighbourhood. The author also describes the architecture and urban environment of the entire Lucknow of the time, with its elaborate mannerisms, all of which contributed to the making of Jamal Mian’s personality.

This was a time when old social values were in decline and a rupture between the old and the new was underway in every sphere of life. This rift came to characterise Jamal Mian’s life and is a major reason why his personal journey is worth studying and reading about. His personal journey, in fact, cannot be understood without understanding the social milieu of those times, which had a strong bearing on his life and personality.

His father’s Farangi Mahall was often a venue for high profile political activities and leading personalities – Gandhi, the Ali brothers, Motilal Nehru – were frequent visitors to it. Jamal Mian not only got a chance to interact with these luminaries at a very early age but also became witness to how some Muslim personalities put their personal interests above the interests of Indian Muslims. At one stage, his father refused to see his own disciple Muhammad Ali Johar because he had reportedly supported the demolishing of the green dome – the much revered gumbad-e-khiza – of the Prophet’s mausoleum if Sharia so required.

Around three months later – in January 1926 to be precise – the news came that Ibn Saud had taken over Hijaz (the region where the holiest Muslim cities of Mecca and Madina are located). Abdul Bari was opposed to Ibn Saud’s Wahabi ideology but Johar was one of its most ardent supporters in India. He wrote in his Hamdard newspaper that he “would not hesitate to break [his bonds with the ulema and Sufis of India] if truth and God so beckoned”. He then renounced his allegiance with Abdul Bari who felt so devastated that he suffered a stroke and died within a week. His death was widely mourned. Shops were closed down in Lucknow and madrasas of the Deobandi and Barelvi persuasions called off their classes.

Jamal Mian was only seven years old at the time. Despite the best education in traditional Islamic sciences that he had received, he was not prepared for the responsibility that had fallen upon him — of providing religious and political leadership to the Muslims of North India.

It was obvious that he could not match the stature of his father in political acumen and religious scholarship but he still managed to develop cordial personal relations with people of import, thanks to his own social skills and the head start he had as a scion of Farangi Mahall. The contribution of these connections is quite visible both in his subsequent politics and business.

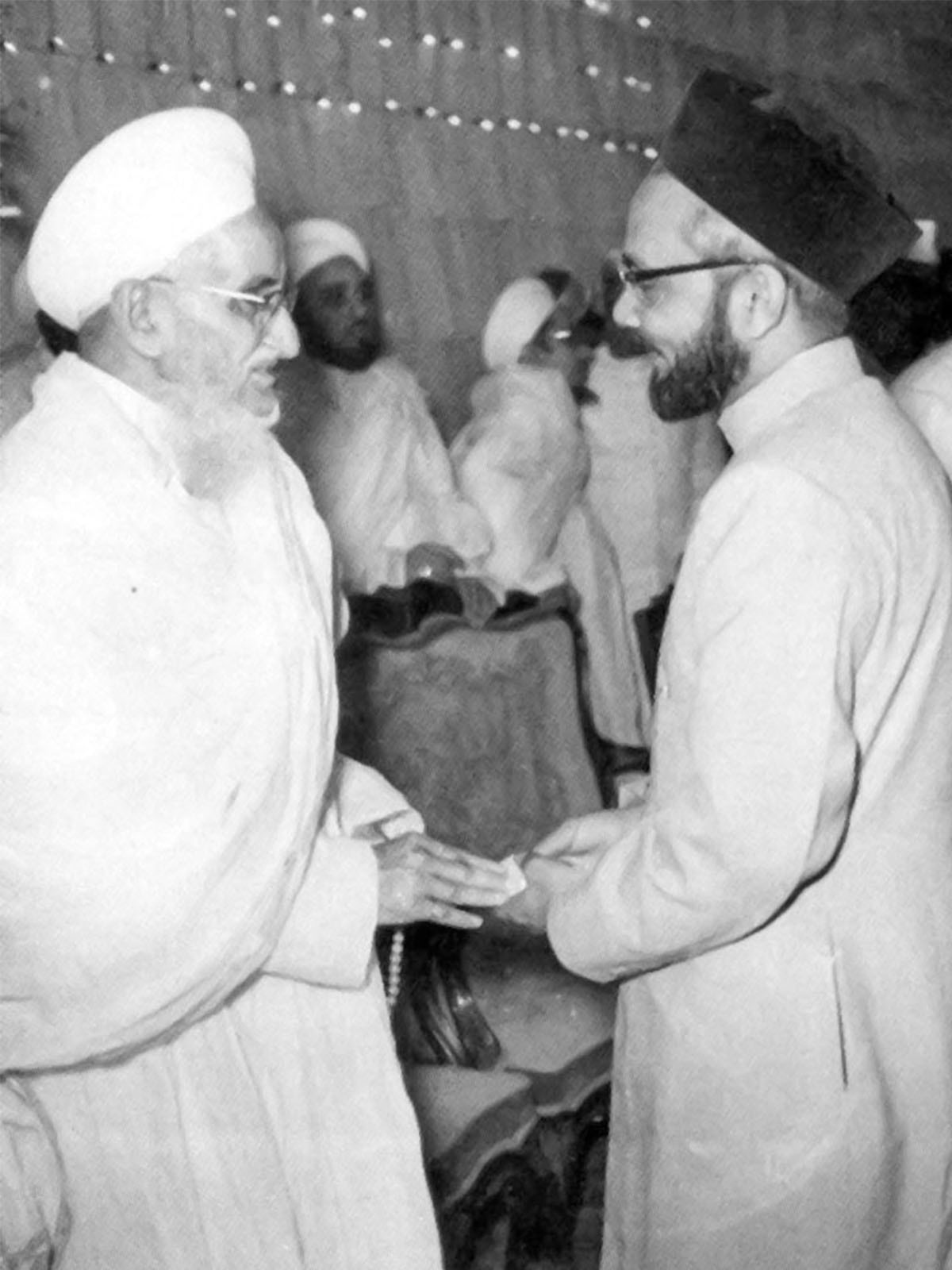

The Ispahanis, the famous Muslim business family based in Bombay that contributed generously to the cause of Muslim politics in pre-Partition India, made him a dealer of their brand of tea. Some frowned upon the idea. Others like Pir Mehar Ali Shah of Golra helped him, in unexpected ways, to sell more tea. In politics, Jamal Mian caught the eye of Jinnah who saw in him an ideal Muslim scholar whose life was compatible with Quaid-e-Azam’s own modernist/westernised worldview. The All India Muslim League made him a candidate in the 1946 election for a United Provinces assembly seat. His successful electioneering in Bara Banki area has been recorded in great detail by the noted scholar of Urdu studies, C M Naim, who witnessed it as an 11-year-old.

From then onwards, Jamal Mian established himself firmly as the head of his family, ran a successful business and built connections across the newly created divide between Pakistan and India. Yet he often found himself on the wrong side of history. Robinson documents Jamal Mian’s personal tragedies and the general sense of loss he experienced, but does not feel that his subject suffered from a lack of political vision or commitment when it came to his attitude towards certain key moments in the history of Indian Muslims after 1947.

It is true that things fell apart for India’s Muslim aristocrats after Partition, which, ironically, was an unravelling of their own making, but that could not absolve the likes of Jamal Mian and others of their responsibility to have offered leadership to their community in this moment of crisis. He, instead, chose to dissociate himself from Indian politics at a time when he was most required to be politically active in that country.

The Indian annexation of the state of Hyderabad through force and the general treatment meted out to Indian Muslims, coupled with a decline in his own commercial fortunes, made it clear to him that life in India was going to be difficult for him. He was, after all, selling a brand of tea owned by Ispahanis who were very openly associated with Pakistan. He, thus, resigned from his membership of the United Provinces assembly and moved to Karachi.

For over a decade, however, Jamal Mian managed to ignore the boundaries between India and Pakistan, successfully managing his family’s commercial and religious affairs in both countries. He took care of his ancestral property in Lucknow, ran the madrasa at Farangi Mahall and attended the annual urs celebrations of his forefathers in India while at the same time also overseeing his business operations in Pakistan. He spent time with political elites on both sides of the border. He was friends with the members of the ruling Muslim League in Pakistan and supported Congress in elections in India.

This finally came to an end in 1957 when Jamal Mian was forced to choose between Pakistan and India. He opted for the former. Things were working out well for him in the new state. Chaudhary Khaliquzzaman, who as the head of the All India Muslim League in the United Provinces was well known to Jamal Mian, became the governor of East Pakistan in the mid-1950s. This, along with assistance from numerous other connections, helped Jamal Mian set up his tea business in Dhaka as well. He also supported Ayub Khan’s military coup and the subsequent martial law regime – actively campaigning for his presidential election in 1964-65 against Fatima Jinnah – and benefitted immensely as a result. Nawab Amir Muhammad Khan of Kalabagh, who was then governor of West Pakistan, gave him a permit to establish a sugar mill. In his diaries, though, Jamal Mian recorded that he enjoined Ayub Khan to do the right thing by the country and its people. Jamal Mian suffered a second displacement when he had to leave Dhaka in 1971 amidst the chaos and violence of civil war. But the business and property he lost in East Pakistan was compensated by his newly set up Shakarganj Sugar Mill, which had become functional by the time he relocated to Karachi. Karachi was an ideal abode for an ageing migrant like Jamal Mian to spend the rest of his life in retirement. “In nearly two days, I realised that I had not just arrived in Karachi but also encountered Hyderabad, Bombay, Calcutta, Jaipur and God knows how many other cities, friends, relatives, connections. They seemed to have been assembled from all over the place,” he wrote in one of his diary entries.

Apart from his regular visits to London and Saudi Arabia and his participation in religious ceremonies as well as the meetings of the Rabata Alam-e-Islami (the Muslim World League), a non-governmental organisation, he restricted himself to the city from 1980s onwards, spending time with Karachi-based members of the old United Provinces elite.

His children were grown up by then and had become more astute businessmen than him. None of them, however, carried forward the family’s tradition of religious scholarship. The remarkable journey of a religious family had finally taken a worldly turn.

Robinson has certainly written about a particular member of a particular North Indian sharif (noble) family but in doing so he has conjured up a whole social and cultural milieu that resonates with so many other individuals who have similar experiences and personal trajectories. The author successfully delineates how an entire social, political and religious tradition nurtured over centuries underwent a complete transformation in the 20th century — as is manifested in the lives of Jamal Mian and his children in Pakistan. Once uprooted from their place of origin, they also ended up dissociating themselves from their family’s original mission — of providing leadership in the social, political and religious spheres of life.

This article was published in the Herald's May 2018 issue. To read more subscribe to the Herald in print.