Allahdad was woken up in the middle of the night by the thunder of shelling and what sounded like Kalashnikov fire. Half-asleep, he and his neighbours stumbled to the rooftops of their mud-brick homes in Chaman city to determine the source of the ominous sounds. A battle seemed to be taking place a couple of kilometres to the west, near a border crossing that links Chaman with the town of Wesh in Afghanistan.

Allahdad went back to sleep only to wake up again at 5:30 am. He was to report for duty in less than two hours as the member of a census-taking team in his native area. At 7:00 am, he arrived at a local base of the Frontier Corps (FC) about 2.5 kilometres from the Afghan border. The officers there told him that he and another enumerator were to conduct census in Roghani check post area behind Chaman’s Government Degree College. As soon as they left the base in an FC vehicle, they found that they were instead headed westwards. Allahdad was surprised. He asked the FC officials accompanying him why they were going towards the border where fighting was taking place. He received no answer.

Allahdad and his companion spent the next five hours within the battle zone, sandwiched between two militaries exchanging heavy fire. “We took cover behind a wall,” he says on the phone from Chaman weeks later. A tank was posted right behind them. It was firing shells inside Afghanistan. Carrying only green waistcoats that had ‘Pakistan Census 2017’ written on them and carrying stationary needed for census taking, they felt like sitting ducks. Allahdad says he repeatedly asked the FC soldiers to provide weapons to him and his two associates. “If you want us to fight for our country, then at least give us a weapon,” he said to the soldiers.

Allahdad, a school teacher with 20 years of experience, would later find out that firing from the Pakistani side on that day in early May this year was in retaliation to what a military spokesman called “unprovoked” hostility from the Afghan side towards census takers and the FC soldiers accompanying them. The number of people who lost their lives in the crossfire remains disputed — it could be anywhere between 15 and 50 depending on who is counting. The dead include Afghan soldiers, Pakistani security personnel and civilians from both sides.

Prior to the skirmish, tension had been building up for days between the border forces of the two countries over Pakistani efforts to conduct the census in two border villages — Killi Luqman and Killi Jahangir. Both Pakistan and Afghanistan claim that the villages are located on their side of the Durand Line, a 2,600-kilometre border that has been often contested since it was drawn to separate Afghan territories from British India in 1893.

Following the border clash, Allahdad took a break for a few days before returning to his census duty, but he was still wondering why he and the other enumerator were taken right into the middle of the battle. Such scepticism towards the state in general and security forces in particular is not uncommon in his native Balochistan — a province where the army and other paramilitary forces are not always treated with love and respect.

This perception of the security forces could have had serious implications for a task recently assigned to the army: to accompany census teams and note down and verify demographic information about the occupants of households — in addition to the documentation done by civilian enumerators. The ostensible objective of this move, as explained by Rana Mohammad Afzal Khan, parliamentary secretary for finance, revenue, economic affairs, statistics and privatisation, during a speech in the National Assembly last year, was to add credence to the data collected during the Sixth National Census carried out in two phases between March 15 and May 25.

Asif Bajwa, chief statistician of the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (PBS) and the man in charge of the census exercise, also said that the soldiers were meant to be “neutral observers” who would conduct an on-the-spot verification of the demographic data collected.

Their neutrality, however, has never been a given.

The United Nations stipulates that every country conduct a national census every ten years. The 1973 Constitution requires the same, though Pakistan has twice failed to do so since 1981. The census due in 1991 was carried out in 1998 and the one to be conducted in 2008 was finally done in 2017.

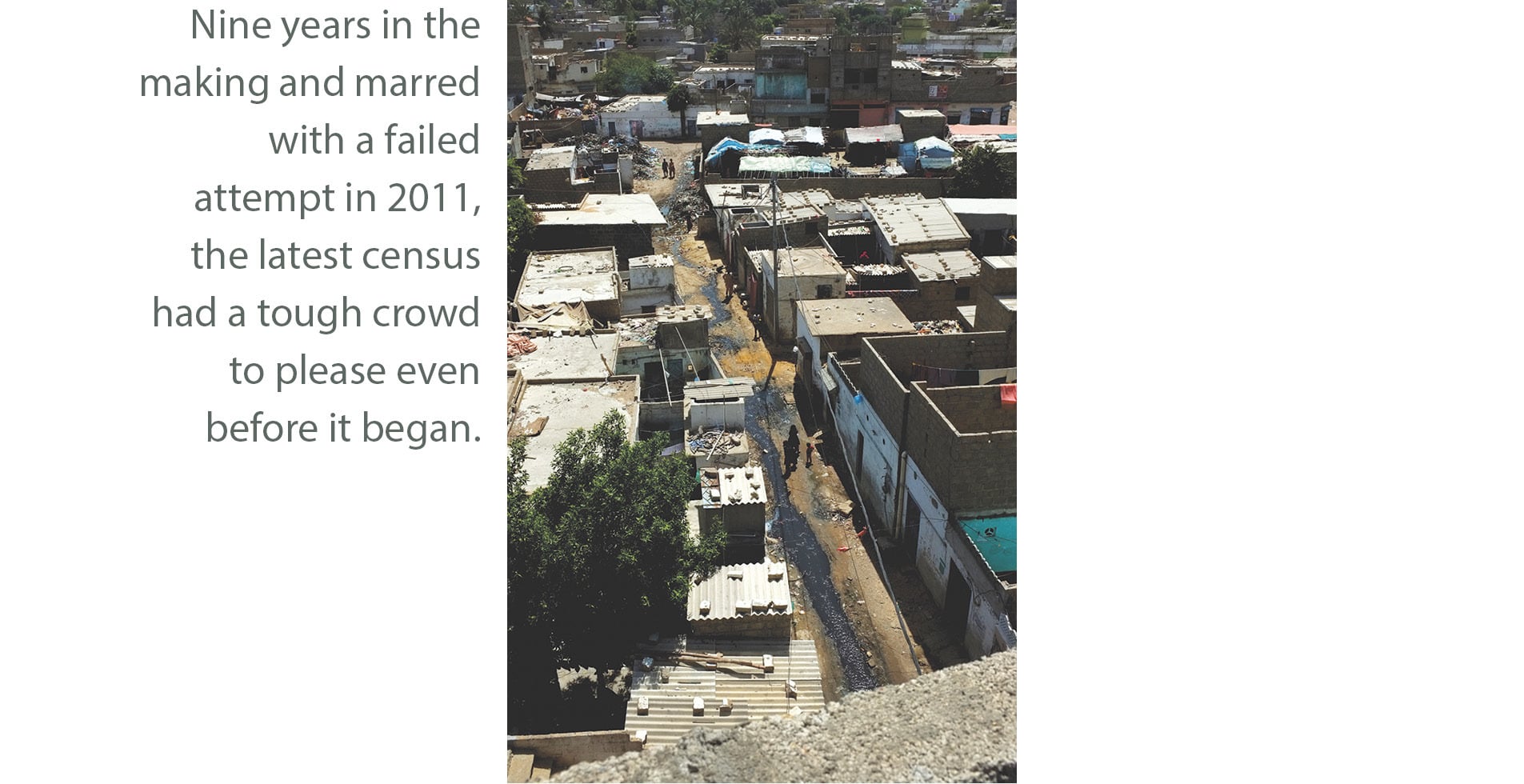

Nine years in the making and marred with a failed attempt in 2011, the latest census had a tough crowd to please even before it began, including a three-member Supreme Court bench — headed by then chief justice Anwar Zaheer Jamali. After hearing multiple petitions for months and listening to one reason after another for the delay – including the unavailability of security officials to provide protection to census staff in strife-torn areas – the judges lost their patience in December 2016 and told the government to hold the census within the next three months — or face legal action. The PBS – formed in 2011 through a merger between the Federal Bureau of Statistics, the Population Census Organisation (PCO) and the Agricultural Census Organisation – scrambled to make arrangements to get it done within the short time given to it, leaving many gaps and lacunae in its procedures and processes.

Fieldwork for the census was carried out with the active involvement of 200,000 soldiers from the army. They were not just meant to provide security to 91,000 civilian census workers but were also tasked to complement data collection and cross-check it on the ground. In most areas, other security agencies such as the navy, FC, Rangers, police and Levies were additionally engaged in providing security to census teams.

This was not the first time that the government had turned to the army for assistance in collecting demographic data. The soldiers’ involvement in the exercise was first considered shortly after the controversial house count in 1991 that showed that Sindh’s population had more than doubled since the previous census in 1981 — from 19.03 million to over 50 million people. That the province’s population remains below that figure by two million people even after the 2017 census suggests how flagrantly flawed the 1991 numbers were. The reason for the highly inflated numbers, analysts speculate, was that the Mohajir Qaumi Movement, which later became Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM), forced enumerators to overcount households in urban parts of the province, especially Karachi, where the party’s support was concentrated.

The then federal administration of the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PMLN) consequently decided that it needed the army’s help to go ahead with the next phase of the census — a headcount. But the entire census had to be called off indefinitely after it became apparent that even the army would not be able to move, and count houses and people freely, in many parts of Karachi and Hyderabad due to resistance by the MQM cadre.

When the census finally took place in 1998, it did have soldiers accompanying enumerators. Their presence was meant to ensure that political parties and groups with vested interests could not influence or harass civilian census takers into fudging the data. The soldiers were also supposed to double-check if members of any community, group or political party were lying to census officials in order to inflate their numbers.

Yet, various sections of society in various parts of the country rejected the results of the 1998 census as being flawed, if not entirely false. In Balochistan, many Pakhtuns refused to be counted at all because of what they perceived to be a biased approach towards data collection. The Sindh Assembly also rejected the numbers as being doctored. “When things come to Islamabad they are cooked up and somebody else takes the broth,” Benazir Bhutto, then heading the parliamentary opposition, said in the National Assembly. She was apprehensive that the census results were fudged to benefit the then ruling party, PMLN.

The 2011 survey, too, could not go beyond house count even when it was conducted under the army’s supervision. Asif Bajwa, who was working as the PBS chief at that time too, refers to its results as “atrocious”. Habibullah Khattak, then chief census commissioner, also admitted before the National Assembly’s committee on economic affairs and statistics that the house count in Sindh did not match the trends of previous censuses and various demographic studies.

The same pattern of dismissing – or at least disputing – demographic data persisted after the PBS released the preliminary “summary” results for the 2017 census late this August, putting the country’s total population at 207.8 million. Several political parties, including the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) that rules in Sindh, believe that the province’s population – put at about 47.9 million people and showing an annual growth rate of 2.41 per cent – is grossly understated.

According to MQM’s estimation, the census data is a conspiracy to undermine the party’s urban vote bank since it shows Karachi’s population to be 14.9 million people — far below many previous guestimates. Farooq Sattar, the chief of his own faction of the MQM, called the data “rigged”. Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf has also expressed doubts over the population of the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (Fata) being five million. The party said the census did not seem to have taken into account the people displaced from tribal areas.

A policeman was injured when a census team came under attack in the Mandni area of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa’s Charsadda district within a week after the census had started. On April 5, four army soldiers, an employee of the air force and two passers-by died while 18 others were injured in a suicide bomb attack on a census team in Lahore’s eastern outskirts. Less than 20 days later, a security official lost his life and another was injured when unknown attackers hit a census team near Pasni town in Balochistan’s Gwadar district. In all these instances, security officials accompanying the census officials could not prevent terrorists from striking.

The presence of heavily armed soldiers in combat fatigues might have protected the census teams from possible coercion, even violence, by groups, communities or individuals bent upon preventing data collection or trying to mould the statistics in their own favour. But it can also be argued that, rather than being aimed at civilian census officials, the attacks mentioned above were a continuation of the strikes security forces have been facing for years at the hands of different militant organisations ranging from the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan to Baloch separatist militias.

Sending out soldiers to streets and neighbourhoods across the country under such circumstances might have made them more vulnerable to hostile acts than before. In retrospect, it looks like a necessary risk — one that, fortunately, has not led to as many attacks as feared.

But the other risk involved in sending out army officials into civilian areas is the sense of harassment that people may feel, especially in Balochistan and Karachi where the army has a history of carrying out security operations. In some cases, this feeling was enhanced due to attempts by soldiers, taking down demographic data, to find information they were not supposed to collect. At places, particularly in Sindh and Punjab, they wanted to know if the household they were enumerating had any licensed or unlicensed weapons. A senior officer involved in the census in Karachi acknowledges that the army wanted to utilise the opportunity to know how many weapons there were in a certain area. His name cannot be revealed because he did not have permission to speak to the media. Another officer claims it was just a scare tactic so that people possessing illegal weapons got rid of them, fearing government action.

But considering that census teams were not permitted to enter or search homes or lodge cases over weapon seizures, the likelihood of this tactic succeeding looked low from the beginning. No one voluntarily discloses the possession of illegal weapons, let alone giving them up. Also, the fact that residents in Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa were not asked about weapons suggests that no countrywide policy existed to link the collection of demographic data with a deweaponisation drive.

Bajwa also says just that — queries about weapons were not a part of the census officials’ mandate. A few army officers acted on their own in some areas, he says, that too in the early part of the census process. “As soon as we received reports about it, we took up the matter with the army … They said some local commander must have asked [questions about weapons].” The queries then stopped, he adds.

It is 1:00 pm and Anjum Kashif is rushing through her lunch. Since the census began about a week earlier on March 15, she has constantly been attending to phone calls from census workers reporting hurdles from the field. She works as a statistical assistant at the PBS and has set up a control room at the Government Degree College for Boys in New Karachi, also known as North Karachi.

In census jargon, the control room is called ‘charge centre’ and she uses it to coordinate among the army, PBS personnel and other government employees – mainly school teachers and lady health workers – engaged in the collection of census data.

Anjum is a self-proclaimed perfectionist, always willing to go the extra mile to produce quality results. This makes her an ideal candidate to oversee census activities in North Karachi, one of the city’s most densely populated areas. She is taking no days off, sometimes attending meetings at the district administration’s offices or at the local chapter of the PBS after having already spent an entire day in the field. She often goes home late at night even though she has two young children to attend to. Sleep is a luxury for her. “My only wish is to ensure that the work that comes under my watch is done accurately,” she says.

Accuracy, indeed, is the holy grail of any census. In Pakistan’s case, even a perceived lack of accuracy can easily lead to public and political outcries and protests. As far as the recent census is concerned, some of its accuracy seems to have been compromised due to the haste with which it has been conducted. Dr Muhammad Iqbal, a statistics teacher at the University of Peshawar and member of a census advisory committee constituted by the PBS, acknowledges that the government was unprepared for the census. “Due to lack of time, even the census questionnaires used are the ones created back in 2008. These things cause a big impact.”

Outdated maps used for dividing neighbourhoods into census blocks – each consisting of around 250 households – constituted another major problem, says a report prepared by observers deployed by the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) to monitor the census process.

Anjum concurs. She received frequent complaints about the census blocks from many of the 500 or so census enumerators she worked with. About 10 per cent of the 905 blocks under her jurisdiction turned out to have more households than they were supposed to, she says. Some of them exceeded their supposed size by three times. One enumeration supervisor working in Khwaja Ajmer Nagri neighbourhood of Karachi discovered a block that had 700 households, she says. He immediately contacted Anjum who visited the area herself. Trudging up a steep slope to get a proper view of the settlement, she realised why the supervisor was right. The neighbourhood was too big and too thickly populated to have only a few census blocks. On her recommendation, it was remapped and divided into 22 blocks.

Size was not the only problem with the blocks. Based on old maps, they were sometimes also difficult to locate. In many cases, their geographical reference points – such as street names and locations of local landmarks – had changed so much that they had all become mixed up. Anecdotal evidence from various districts in Sindh, Punjab, Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa suggests that many maps used in the census process could have been made as far back as 1998.

A PBS representative in central Punjab’s Kasur district guestimates that 20 per cent of the maps in that district were not updated after 2011. Similarly, a school teacher conducting the census in Mastung district of Balochistan says that census blocks were based on mapping conducted 17 to 20 years ago. In both places, outdated maps were a major reason why a census block had 700 to 800 households — a number that was impossible for a single enumeration team to cover within the census timeline.

Bajwa concedes that there were some “areas where nobody was living when the maps were updated but now there is a 14-storey building standing there”. The PBS, therefore, had anticipated that there could be problems with blocks, particularly in peri-urban areas (located on the outskirts of a city/urban area) where population has increased rapidly and construction of new roads/streets and buildings has taken place at a very fast pace, he says. But he rejects the suggestion that some of the maps were two decades old. Official mapping for the purpose of forming blocks was carried out in 2014 in rural areas and it was completed by the end of 2015 in urban areas, he says.

Shahid Mehmood Tahir, 50, is a newspaper distributor and public school teacher in Sheikhupura, about 50 kilometres to the west of Lahore. Working as a census enumerator in his home town, he got an extraordinary assignment — counting prisoners in a local jail.

When Tahir and his census associates reached the jail they found that there were 2,200 people imprisoned there. “The life of a prisoner is completely different from the life of an ordinary person,” he says about his experience of being inside the prison. “It is a separate world.” Soon he also found that many prisoners had no interest in being counted as part of the national population and were extremely reluctant to share their personal information. “They did not like to give answers immediately. We had to wait for them to respond to our questions,” says Tahir.

“Sometimes they gave such odd answers, one did not know how to write them down.”

He remembers meeting one prisoner and asking him to show his Computerised National Identity Card (CNIC), or shanakhti card in local language. “What is a shinakhti card?” said the prisoner. Some prisoners wanted to share their life stories with enumerators. A 10-year-old boy, in prison on murder charges, narrated to Tahir how he got into an altercation over a game of cricket and ended up hitting another player fatally with his bat.

In the case of female prisoners, the enumerators had an additional problem. Women were kept in a part of the jail where men were not allowed to enter. Tahir and his colleagues had to stay where a female constable was standing, guarding the prisoners. The jail staff helped them get the information they required, he says.

These difficulties in a confined place offer a micro-level picture of the obstacles that census enumerators were up against in streets and neighbourhoods across Pakistan.

Some residents in “posh” neighbourhoods were difficult to get a hold of, says Tahir. Many in places such as Karachi and Quetta mistook census officials for the much-shunned polio administering teams. One of the biggest logistical difficulties was access across many rural and conservative parts of the country. A census official in Kohat, for instance, had to speak to a woman through an iron gate.

Also consider the case of Killa Saifullah district in Balochistan. The recent census has put the district’s population at 342,814, having increased at an annual rate of 3.05 per cent since 1998. Women account for 46.95 per cent of the local population and yet an outsider will be hard-pressed to find even a single woman in public — not even in bazaars.

If they have to go for shopping or they need healthcare, they will go to either Quetta or Karachi but will not venture out in their own district, says a local resident. “There is a restriction on women here.” Out of respect for men in the family and the strict social code prevalent in the area, adds a local teacher, some women do not utter even the names of their husbands and male in-laws. A woman in Killa Saifullah having to encounter a male enumerator would not have even disclosed the names of men in her family let alone provide personal details about herself.

Many enumerators did not have sufficient training. For instance they did not know the difference between literacy and education, says the report by UNFPA observers. As a result, the report adds, people who were literate but had not attended school were considered illiterate. Observers have also reported problems with the enumeration of transgender individuals and persons with disabilities in all four provinces, says a report in daily Dawn.

Some of these flaws can be attributed to the timing of the census — coinciding with the busiest part of the academic calendar. “… government schools conduct their internal exams in February and March. Board exams for classes five and eight (in Punjab) also take place in these two months. This year, these activities overlapped with the census enumerators’ training,” this magazine reported in March 2017. “These are then usually followed by matriculation and intermediate exams in April and May — happening almost concurrently with the two-phased census exercise this time round.”

It was perhaps this coincidence that made Punjab Chief Minister Shehbaz Sharif initially announce that no teachers were to participate in census taking in the province. He later revoked his decision but his reluctance hampered the training of many teachers for their census duties. “Up to 170 teachers did not show up for training” in Kasur alone, says a census official.

The Punjab education department also barred headmasters from joining census teams, he says. Constituting more than 20 per cent of primary school teachers in the province and being the most experienced and the most qualified members of the staff at schools, they could have brought with them the experience and authority the PBS so needed in its census operations.

It was in order to remove – or at least reduce – the impact of such flaws that the PBS set up an advisory committee of experts including people such as Dr Iqbal of Peshawar University, Dr Mehtab Karim, vice chancellor and executive director of the Centre for Studies in Population & Health at Karachi’s Malir University of Science and Technology, and Dr Zeba Sathar, director of the Pakistan Population Council, a non-governmental organisation working on family planning and family healthcare.

One of the most important recommendations the committee made was a post-enumeration survey to determine what percentage of the population was not counted or was under-enumerated during the census. The PBS rejected the recommendation. Its officials are said to be worried that any discrepancies found as a result of the survey would expose them to hostile criticism. Instead of seeing it as a useful tool to identify errors of omission and commission in the census, they feared it might jeopardise the credibility of the whole census exercise. Even in 1998, they pointed out, no such survey was conducted.

Making a case for the survey, Karim argues that it is not essentially meant to find fault with a census or the takers of a census. He makes a distinction between “undercounting” and “under-enumeration”. The former, he says, implies deliberate omission while the latter suggests defects in methodology. A post-enumeration survey will at least show if any people have somehow been left out of the count and what their possible number is, he says, and adds that a census conducted in a vast and thickly populated country like ours is likely to under-report some numbers. Even a developed and thinly-populated country like Australia has recorded 2 per cent under-reporting in its census, he says.

His own calculations – based on annual population growth rates derived from the Pakistan Demographic Surveys conducted intermittently between 1982 and 1997 – show that the population was under-reported by about five per cent in the 1998 census. This equals to around six million people. The surveys he relied on were discontinued after 2008, making a post-enumeration survey even more important to track problems in the census.

Karim believes the major problem in the 2017 census pertains to Sindh and Punjab’s data [Figure 1A]. How is it that the average household size has been dropping in Sindh regularly? From seven persons per household in 1981 to six persons in 1998 and to 5.6 persons in 2017 but it remains the same for Punjab – around 6.4 persons per household – between 1981 and 2017, he asks.

This, he says, contradicts the findings of the Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey, published by the National Institute of Population Studies in December 2013, which suggest that family planning programmes in Punjab have fared better compared to the ones in Sindh. The survey states that decline in fertility rate since the 1990s has been highest in Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (at 29 per cent) and slowest in Sindh (at 23 per cent). Even Balochistan (at 27 per cent) had a steeper decline than Sindh.

Bajwa of the PBS, however, dismisses the need for a post-enumeration survey. A “neutral observer” – an army man – accompanied each enumerator during the census which means that the data collected is already double-checked, he says. There is, therefore, no need for any other survey, he adds.

Karachi’s Orangi Town is home to a large number of ethnolinguistic communities — Pakhtuns, Baloch, Afghans, Sindhis, Bengalis, Biharis, Banarasi and other migrant groups with Indian antecedents. A picture of government neglect, the town is known to be one of the world’s largest slums and has an estimated population of 2.4 million people (the 1998 census put its population at 721,694). This densely populated area is plagued by water shortages, poor sanitation, lack of schools and healthcare facilities, to name just a few of the civic amenities that are either non-existing here or are in bad shape if they can be spotted at all.

Within the northeastern periphery of Orangi Town lies Baloch Goth. Meandering through its narrow and congested streets, one may pass by several neighbourhoods each with its distinct ethnic makeup. From the elusive and isolated Afghans to Banarasi silk weavers who had migrated to Karachi after Partition from Banaras, present-day Varanasi in India’s Uttar Pradesh state, the goth offers a slice of Pakistan’s demographic pie with every ethnic taste in it.

Only 2,500 people lived in Baloch Goth in 1998, says Muhammad Juman Darwan, a local political activist associated with the PPP. He guestimates that figure has increased at least threefold. Residents here are hoping that the latest census will help them make a case for their civic needs. If the government has the most updated figures for population, it will be in a better position to plan and provide resources and services to those who need them the most — goes the local logic.

If government money and census data are closely linked, then it is important to ensure nobody is left out of the count — or is overcounted. Darwan, a two-time head of the Baloch Goth union council, therefore, has been monitoring the census exercise very closely. “We have conducted a census of our own and we will tally it with official results,” he says.

Wearing a crisp white shalwar kameez and a red Sindhi cap on a late March day, Darwan knows Baloch Goth, his birthplace, like he knows the back of his hand. He has lived here all fifty or so years of his life. Although an MQM man won a Sindh Assembly seat from the area in the 2013 general elections, Darwan says it is his duty to ensure that distortions in the census process do not harm the interests of local residents. Sitting outside his office located inside a single-room structure and furnished with a lone table, a few chairs, and a poster showing Darwan shaking the hand of PPP chief Bilawal Bhutto, he is greeted warmly by a census team accompanied by several officials of the Pakistan Navy and the police. He has established a friendly rapport with them since the census began a few days earlier.

“We would not have trusted school teachers alone,” Darwan says. His mistrust is rooted in his experience of the 2011 census when teachers were pressured by a political party into using an impermanent pencil to note down information on census forms, he says. This made it easy for the party to change the information before sending it to senior census officials, he adds. As a result, he claims, one household was counted as three. This time around, “the military’s presence is reassuring”.

A few months later, as the initial census results are released, Darwan is anything but assured. “Now you can see for yourself. It is a mess, isn’t it?” His doubts are strengthened when the district administration invites him to a meeting to verify the boundaries of certain census blocks in Manghopir area. “Why are they going into this [verification] after the census results have already been released?”

Darwan says his worst fears have come true: the census does not reflect the immense migration to Sindh that has taken place, specifically to Karachi (where population has risen by only 5.56 million people since 1998). According to the previous census, Lahore, Faisalabad, Multan and Rawalpindi together received the same number of internal migrants between 1981 and 1998 as Karachi alone did. Every fifth person who left his native village or town ended up in Karachi during that period. Considering that far more migrants have moved to Karachi than any other city over the last decade and a half, the population of migrants here seems to have been under-reported if not deliberately undercounted.

Khawaja Ajmer Nagri illustrates this. Cordoned off on one side by a hill where some people have built their shacks and a dilapidated road, strewn with trash and sewage running on its other side, the locality – like Baloch Goth – is home to people from across Pakistan. About a kilometre from Power House Chowrangi, it has residents who come from a number of ethnolinguistic backgrounds — Seraiki, Sindhi, Pashto, Punjabi and Urdu. The locals dismiss the botched house count of 2011 as “ridiculous”. They claim it put their neighbourhood’s population at 2,500 even though the 1998 census had recorded it to be 19,000.

That this data was flawed became apparent when the census blocks in Khawaja Ajmer Nagri had to be revised upwards by 200 per cent in the latest census. Another proof of the neighbourhood’s high population comes from polio vaccination campaigns which suggest that just the number of children under the age of five living here is around 14,800. This number, according to estimates by international organisations such as the World Health Organization, represents about 17 per cent of the locality’s total population. Going by this formula, the number of people living in Khawaja Ajmer Nagri should be around 87,500.

Census authorities have not yet revealed locality-wise data for settlements such as Baloch Goth and Khawaja Ajmer Nagri but Karachi’s overall statistics have political activists like Darwan worrying. He speculates that the PBS must have included many migrants living in Karachi in the population of the districts they originally belong to.

The other problem with the census data for Karachi is the confusion about non-Pakistanis living in the city — Burmese, Bangladeshis, Afghans, Iranians among others. Does the census data include them or will they be counted separately? A large, but unspecified, number of them may have already been counted as Pakistanis since they have acquired Pakistani identity documents.

Experts like Karim believe that counting aliens separately is not what a census ought to be doing. “A census has nothing to do with citizenship. [Its requirement is that] everybody must be counted irrespective of whether he or she is a Pakistani citizen or not,” he says. “It is simply about knowing how many people live in a country or a locality.”

Fazal Amin, 21, belongs to the Sipah subtribe of Afridis and is a resident of Bara tehsil in Khyber Agency, which is one of the seven Pakhtun regions along the Pak-Afghan border that together form Fata. He has recently completed his bachelor’s in business administration from a university in Peshawar and is working as the head of Sipah Youth Organisation, a local activist group. He is one of the many locals who claim that Fata’s population has been deliberately undercounted in the latest census.

“I can point to so many instances where the discrepancy is obvious,” he says. “For example, the Akakhel tribe living in Khyber is known to have at least 90,000 voters but they have been counted by the census to be between 30,000 and 35,000 people.” Many Akakhel families, he claims, have not even been approached by census officials. He is concerned about the census data because he understands that it has serious financial and economic implications. “An undercount will adversely affect Fata’s development funds, our share in the National Finance Commission (NFC) award, quotas in government colleges and jobs and our representation in the provincial assembly in case we are merged with Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.”

Amin’s organisation guestimates Fata’s population to be around 8.5 million — far higher than most other estimates. The Fata Research Centre, a research organisation based in Peshawar, estimates the tribal areas’ population to be around 4.6 million — roughly in line with the latest official figure of 5,001,676. Yet, Amin insists that census figures are unreliable because they have not taken into account internally displaced people (IDPs) — tribesmen living in different parts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa after being displaced by conflict and violence in their native areas. “There were about 1.2 million IDPs, according to the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa government, back in 2009,” he says. That number should have increased since then, he adds, considering that there have been subsequent displacements from North Waziristan and South Waziristan as well as from Kurram, Khyber and Mohmand agencies.

Official estimates indicate that the number of IDPs has gone down rather than having gone up. Only 500,000 tribespeople – or 75,000 families – are waiting to return home, says the government. The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs in Pakistan, on the other hand, claims that “a total of 5.3 million people in Fata have been displaced since 2008”. If this figure is to be taken as a basis for the population of the tribal areas, then far more than five million people should be living there. But, perhaps, the UN data is counting a large number of IDPs twice or thrice since many of them have been displaced more than once over the last nine years.

All these various figures are confusing, if not worse. “As per my observations, the enumeration of the IDPs during the census has been completely disorderly,” says Amin. One of his biggest complaints is that many IDPs have been included under the population of districts where they are temporarily residing. “Why have they been counted as residents of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa when they are ultimately going to return to Fata?”

Iqbal, the statistics teacher, explains that census teams have justifiably counted those IDPs as residents of the province. “The rules of our census clearly state that any person living in a place for over six months must be counted in that place,” he says. “A huge number of people from the tribal areas have now permanently settled in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. They are no longer IDPs. It is unlikely that they will ever return [to their native lands],” he says. “You can’t be expected to be counted in Fata if you have been an active socio-economic resident in Peshawar for years.”

Bajwa, however, explains that the IDPs have been temporarily counted among the population of those districts they are residing in. “During the [data] processing stage, they will be adjusted to their original areas based on coordination with the Fata disaster authority.”

Ismutullah Shah, a teacher of Seraiki language at one of the oldest colleges in Bahawalpur, is apprehensive that speakers of Seraiki may have been undercounted in the latest census. The 1998 census put their number at about 10 per cent of the country’s total population and at 17.4 per cent of Punjab’s population. In Bahawalpur district, more than 60 per cent of the population was shown as Seraiki-speaking. Shah fears that these numbers may have changed for the worse for Seraiki speakers.

Activists like him fear that many younger Seraikis, especially in urban parts of Seraiki-speaking areas, might have listed Urdu as their mother language in forms for the recent census. In a 2014 interview with this magazine, Shah had lamented that people from his community discouraged their children from speaking Seraiki at home due to what he called a “misconception” that learning Urdu provided more job opportunities. “Homes have become slaughterhouses for Seraiki language,” he had said.

In rural areas, there was the opposite problem of people not really knowing the importance of registering themselves as Seraiki speakers. Bahawalpur has a rural population of about 70 per cent (as per the last two censuses) and, according to the 1998 census, about 80 per cent of Seraiki-speaking residents of the district lived in rural areas. Most of them are also illiterate, especially those scattered in the vast Cholistan desert. Seraiki activists like Shah fear that Seraiki speakers in these parts might have ended up noting down Punjabi as their mother language. Being illiterate and simple village folk, they could have confused their language with the province they are residing in. Most census enumerators in Seraiki areas were also Punjabis, activists further allege, and they might have attempted to undercount Seraiki speakers.

To preempt all this, activists embarked upon a campaign to raise awareness in the months leading up to the census, says Shah. One Facebook video – shared by a Seraiki activist – shows a gathering in the “rural areas of Cholistan” where a speaker is instructing a crowd to ensure that they are registered as Seraiki speakers. The campaign seems to have not achieved much since Seraiki nationalists have rejected the latest census figures as inaccurate. Though the PBS is yet to issue language-related demographics, Shah calls the census data “politically motivated” and “economically biased”.

Abdul Hakim is a senior public school teacher in Hub, a city in Balochistan’s Lasbela district. At 9:00 am on an April morning, he is sitting in a small room at a charge centre off Hub’s Adalat Road, recounting his experience of going to a local family as part of his census-taking duties. His first encounter was with two children.

He asked them about their mother language.

“Urdu,” they said.

Hakim was surprised at their response. He knew their father — he is a Sindhi.

He sent the boys back inside the house to confirm their mother language through an elder in the family. They returned and still insisted on Urdu being their mother language.

He ended up noting two different mother languages spoken by the family — the two boys and their father were recorded to be Sindhi-speaking and their mother as Urdu-speaking.

A situation like this mostly resulted from an enumerator’s failure to explain what mother language is or confusion amongst people to understand its definition correctly. Does mother language mean the language of general conversation within a family; does it refer to the first language we learn at home; or is it the language that also connotes our ethnicity? “This is a grey area and it is confusing,” says Hakim.

Due to its proximity to Karachi and its own expanding industrial and commercial activities, Hub has drawn people from all parts of Balochistan as well as from Sindh, Khyber Pakhtunhwa and Punjab over the last two decades. There is anecdotal evidence that suggests that many Baloch families displaced from strife-hit districts such as Awaran have shifted to Hub — as well as to other parts of Lasbela district. It is not unusual to hear local residents speak in diverse languages such as Pashto, Gujarati, Seraiki, Gilgiti and Punjabi alongside the local dialects of Balochi and Brahvi. Local journalists and government employees claim that population-wise Hub is the second fastest growing settlement in Balochistan after Quetta.

The 50-kilometre drive from Quetta to Mastung town resembles most other journeys by road between major towns and cities in Balochistan — miles and miles of a desert landscape dotted with green shrubs, arid mountains and power pylons. Hours may pass before one sees signs of human settlement.

On May 13, 2017, the town of Mastung is unusually quiet. A day earlier, a terrorist attack here targetted the convoy of Deputy Chairman Senate Abdul Ghafoor Haideri, resulting in the death of 26 people. His party, Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam-Fazl, is observing a strike. Shops and businesses are closed.

For the census officials, however, it is business as usual.

Three FC officials and one civilian enumerator sit on the floor of a local baithak, or temporary community centre, owned by a tailor. It is a room, about 150-square-foot big, with no furniture. A sewing machine is lying in one corner and pieces of fabric are strewn across the room. The heads of many families living close by are all gathered here – identity documents in hand – eagerly sharing information with the census officials. Four policemen stand guard outside as Mastung is an officially declared “sensitive” area because of its long history of sectarian violence and anti-state insurgency. It is from this district’s mountainous area that the bodies of two Chinese nationals were discovered in September this year, around five months after they were kidnapped from Quetta’s Jinnah Town.

Mohammad Wafa, a local teacher, is noting down information as people around him talk in a local dialect. “We are all Baloch here,” says one of them, “even those who speak Pashto.”

The link between language/ethnicity and politics runs deep in Pakistan — even more so in Balochistan where different ethnic/linguistic communities do not trust each other. Pakhtuns living in many areas in Balochistan, including the provincial capital, Quetta, boycotted the 1998 census because the provincial government at the time was headed by a Baloch nationalist party – Balochistan National Party-Mengal (BNPM) – and the Pakhtun parties feared that census authorities would undercount their electorates, regarding local Pakhtuns as Afghans. Killa Saifullah was one of the districts where Pakhtun nationalist parties claimed to have successfully campaigned for the boycott. Many local residents and Pakhtun activists, therefore, dispute the official figure of 193,553 people living in the district in 1998. It was far below the actual number, they say.

This time round, it is the Baloch parties that are pointing out flaws in the census — and they point to places like Mastung to make their case.

The district had around 160,000 people, according to the 1998 census, and most of them were Baloch. Its population has increased rapidly since then. Mud houses now stand along narrow bumpy streets where green crops once swayed in lush fields, the locals say. Most of the people living in these new localities are not Baloch but Afghan refugees who have settled here in large numbers after having acquired Pakistan identity documents. “They should not be counted because they are not a part of Pakistan,” says a man from among the people gathered at the baithak.

Baloch activists claim that a census conducted without repatriating the Afghans – 85 per cent of them being Pakhtuns, according to the United Nations – will result in an extraordinary increase in the number of Pakhtuns in the province.

The BNPM, indeed, filed a petition first at the Balochistan High Court and then at the Supreme Court, seeking the exclusion of Afghan refugees from the census and ensuring the inclusion of the Baloch displaced from their native areas. Many Baloch leaders demanded the government defer the census until all Afghans living in the province were repatriated. Agha Hassan Baloch, the party’s central information secretary, remembers meeting Asif Bajwa, the PBS chief. He was assured that his party’s concerns would be addressed but when nothing happened, “we went to the courts”. In March 2017, the Balochistan High Court ordered census authorities to ensure that Afghan refugees were excluded from the population count and the displaced Baloch were shown in it.

Baloch is not sure if the court order was obeyed but, as Bajwa says, the PBS, as per census rules, had to include in the count all those Afghans who are not living in refugee camps.

He claims hearing reports from Quetta’s Hudda neighbourhood, just three kilometres from the provincial government’s offices, that some census-related documents were being distributed among the local residents. These were copies of the census forms. The locals were supposed to fill personal and family information in them and give them to the census officials. Mother language on all of them was noted as Pashto, says Baloch, calling it “a very big conspiracy”. It is not clear how those forms could have impacted the census. The officials were not allowed to accept filled-in forms from people and each census form, to be accepted, had to have a special computerised code which could not be copied or forged.

Such incidents are a manifestation of the scare that Pakhtuns will outnumber the Baloch if the latter do not make an effort to be counted. According to the 1998 census, about 55 per cent of Balochistan’s population spoke Balochi while 30 per cent of people living in the province spoke Pashto. The Baloch cannot be allowed to become an ethnic minority in their ancestral lands, goes the refrain among Baloch nationalist activists. That is why “most people [in Mastung] want to be counted”, says Wafa.

Baloch politicians point to the phenomenal rise in the number of people living in Quetta district as evidence of a Pakhtun predominance in the province. The district’s population has risen from 773,936 people in 1998 to about 2.28 million people in 2017. Killa Abdullah, a district right on the border with Afghanistan, has registered an equally strong population growth — from 360,724 people in 1998 to 757,578 people in 2017.

The entire Pakhtun-dominated Quetta division has registered above average population growth. The number of people living here has gone up from 1.7 million in 1998 to 4.2 million in 2017, showing an annual growth rate of 4.8 per cent — much higher than the provincial average of 3.37 per cent and more than double the national average of 2.4 per cent.

Another factor important for Baloch politicians and activists is the displacement of thousands of Baloch people from their native areas because of the ongoing conflict between security forces and Baloch separatist militias — this displacement was also mentioned in the BNPM petition as another reason why the census in Balochistan needed to be postponed. Data suggests that the displacement has had serious impact on the population growth rate in many Baloch areas. Awaran – a district wracked by insurgency – has registered only 0.15 per cent annual population growth, possibly due to large-scale displacement of local residents.

Population growth rate, in fact, remains lower than the provincial average in all but five Baloch-dominated districts. One of them is Kech, where population has increased from 413,204 people in 1998 to 909,116 people in 2017. This could be a result of migration to its headquarters, Turbat, from its nearby rural districts of Dasht and Panjgur where clashes between security forces and Baloch militants are common.

"Until they drive us out with sticks, we will never leave,” says Sabir Khan, a teenage resident of Killa Saifullah, a predominantly Pashtun district about 180 kilometres north-east of Quetta. His father, Haji Mohammad Rasool, was born in Afghanistan. Sabir Khan, his bothers and all his nephews were born in Balochistan.

“Why would we go back to Afghanistan?” he says, sitting on the floor of a large room with no furniture in a mud house, located at a 10-minute drive from the main road passing through Killa Saifullah town. When one enters his house through a small metal gate, one has to pass through a thick curtain, walk past the resident livestock and navigate dung and hay strewn all over the floor before entering a room. He is the only male adult at home this evening as his four brothers and father are out taking care of their business.

A tall and thin boy of 15 years of age with a hint of a moustache, Sabir Khan spends most of his days manning one of the two grocery shops his family owns in the town. He had to drop out of school a few years ago after one of his brothers passed away and his father needed him at the shop. Families like his – that came to Pakistan more than a generation ago – own 80 per cent of the businesses in Killa Saifullah, says Ziaur Rehman, a local school principal. Many of them left for Afghanistan earlier this year after the federal cabinet announced a deadline for the repatriation of Afghan refugees.

Those who are left behind are scared these days, says Rehman. They suspect that government officers will nab them and send them to Afghanistan. “They do not get out of their homes and hide their Afghan identity cards.” According to the United Nations Refugee Agency, 300,000 Afghans live in Balochistan as registered refugees. Many others are still unregistered even though they have been living in Pakistan for three or so decades. Given their fear of the authorities, it is easy to understand if they had any apprehensions about sharing their information with census officials, particularly those accompanied by men from the army.

Afghans living in refugee camps in different parts of Pakistan have not even been approached for a count. According to daily Dawn, UNFPA observers based in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa “were not allowed to observe enumeration in refugee villages because no census was taking place there … because of a government directive”. This exclusion, the observers point out, breaches the principle of universality that requires everyone present in a certain place at the time of a census to be counted regardless of their nationality.

Moving through farmland in Mirpurkhas district in Sindh, nine-year-old Radha Bheel and her brother would pick up some watermelons on their way home from school to sell them to people in their village. They used the money to pay their school fee or defer other expenses. Growing up as a member of the schedule castes within the local Hindu community, Radha was pretty independent and was never made to feel that she could not do something because of her gender or religion.

Back then, children belonging to Hindu and Muslim communities mingled together without anyone resenting it. She remembers going out in her early teens with a group of boys – both Hindu and Muslim – to collect grass or sort red chilies or pick cotton. If they encountered a stream on the way, they would swim in it for hours. It was as if I was their sister, she says. The years before she was married, at the tender age of sixteen, played a crucial role in forming her world view.

Originally from nearby Thar, her family moved to Mirpurkhas before Partition and has been living here along with other Bheel families since then. Her father was a farmer but he was well-respected by the local landlords because he was an “untrained lawyer” of sorts and a social activist. “The landlords would often consult him when making decisions.” That is where Radha’s activism comes from.

At 40 years of age, she has five children and a reputation for being the champion of the downtrodden and the voiceless, especially those from the scheduled castes in Mirpurkhas district. Poor and mostly illiterate, according to the 1998 census, around 90 per cent of them live in rural areas. The days of harmony between members of different castes and religions are long past. Members of the scheduled castes face marginalisation not just at the hands of Muslims but also experience discrimination by upper-caste Hindus as well. They, therefore, want the census to count them as Hindus but separate from their upper-caste co-religionists.

Census forms do mention scheduled castes as a separate demographic identity but the text on the form does not make a distinction between a scheduled-caste Christian and a scheduled-caste Hindu. The 1998 census shows that there were about 332,000 people belonging to scheduled castes in Pakistan at the time while the population of Hindus was shown to be 2.1 million. Representatives of the Hindu scheduled castes have been contesting these figures for years. They believe many members of their community have not been counted as members of the group they belong to — they could have been counted as Hindus.

This is how it happens, Radha explains: when census officers ask a scheduled-caste Hindu in Sindh about his or her religion, their obvious response is that they are Hindus. The enumerators note them down as Hindus rather than belonging to the scheduled castes, leading to the under-reporting of their numbers.

In the wake of the 2017 census, several groups that work for the rights of scheduled-caste Hindus in Sindh – such as Dalit Sujag Tehreek, which Radha is associated with, and Bheel Intellectual Forum – have run awareness campaigns within their own community. “We want to be counted as a separate subset of Hindus in the census,” she says. There are two reasons for this demand. Getting clubbed together with upper-caste Hindus deprives the scheduled-caste Hindus of their political significance. The former use the latter for attaining political and economic patronage for themselves. But counted as members of scheduled castes alone and not as Hindus, they lose their religious identity.

Pakistani Christians, just like members of the scheduled castes, believe they too have been undercounted in the past.

“We are the largest minority community in Pakistan,” says Zahid Farooq, a Punjabi Christian living in Karachi. The 1998 census recorded the Christian population to be around 2.1 million and showed Hindus (including those from scheduled castes) to be the biggest non-Muslim community in the country — putting their number at about 2.4 million. That count was inaccurate, he says. Church records of births, deaths and marriages suggested the total number of Christians in Pakistan at that time to be 2.6 million, he claims. “This is an authentic record.” Anyone who contradicts it must visit the four divisions of Punjab – Faisalabad, Lahore, Gujranwala and Sialkot – and they will realise how big the Christian community is, he says.

Farooq has been actively involved in the campaign to have all Christians in the country counted – and counted correctly – in the latest census. He has been living in Karachi’s North Nazimabad area since the 1970s and is no stranger to numbers and demographics. As a director at the Urban Resource Centre, a Karachi-based non-governmental organisation focused on urban and environmental planning, he is always dealing with some kind of demographic data about Karachi — how many people use the city’s roads every day; how many buses and other vehicles are required to transport them; how much land there is in the city; how much of it is available to house low-income communities.

Christian politicians and various church organisations have carried out campaigns to disseminate information about the census and ensure maximum participation in it by their community. Apart from distributing leaflets during prayers at churches, activists made a dummy census form in order to educate members of their community on how to fill it. “We told them to hand over one copy of the filled-in dummy form to the church and the other to the enumerator so as to make it easier for the census teams [to note down data],” he says. This, however, was not taken well by some census officials who thought it was akin to meddling in their work.

Other non-Muslim Pakistanis have fared even worse across different censuses. Buddhists and Parsis were marked as separate religious groups before the 1998 census when they were dropped from the census forms and included in ‘others’. Ahmadis were counted as Muslims before the 1981 census when they were first listed as a non-Muslim community. Sikhs have never found a mention as a separate community in the census. They lodged a petition at the Peshawar High Court to be recognised as a religious community apart from ‘others’. The court ruled in their favour but by then census forms had already been printed. It was impossible to change them, given the money and time required.

Some of these developments reflect the state of non-Muslims in Pakistan who accounted for 23 per cent of the population of the country in 1947. According to the 1951 census, the population of Hindus in Pakistan was 12.9 per cent. The country had the second largest Hindu population anywhere in the world at the time. Many migrations and massacres later, non-Muslims were reduced to 3.7 per cent of all Pakistanis in 1998. What all these minority groups have in common is the feeling that the state has failed them. They also share the hope that recording their numbers accurately will somehow change their status for the better. At the very least, they see a correct count as a step in the right direction.

In theory, says Karachi-based architect, urban planner, researcher and activist Arif Hasan, a census is a very important tool for planning. Information about indicators such as population density, literacy and age may help a government to determine which section of society needs what kind of amenity — by how much and how urgently.

Hasan, however, is concerned about the small number of demographic indicators covered during the recent census. He points to the 1998 census that included a sample survey involving a form known as 2A. Enumerators filled this form at every tenth household they visited, asking questions pertaining to migration such as district of birth, time spent in the current district, the reason for migration, etc. Other important indicators that form 2A addressed concerned infant mortality and reproductive health. It had questions designed for women between the ages of 15 and 50 — how many children have they given birth to; how many of them were alive; how many were born in the last 12 months?

None of this information is collected in 2017. The rate of internal migration, depth of educational attainment including field of study, unemployment, infant mortality and vaccination are other statistics missing in this census. These omissions render it impossible to track social and demographic changes over time and, thus, make it difficult to plan development schemes that are consonant with changes in society. These are massive data gaps in a census that is costing 17 billion rupees to the federal exchequer.

Without information about these important indicators, how will we know the direction and extent of change in society, argues Hasan. “The government and planning institutions are going in one way but society may be going in the other direction.”

PBS chief Asif Bajwa says there is a reason why collection of information about these indicators has been left out of the census. Planning for the census was contingent on the availability of army personnel, he argues. He had originally requested for 500,000 army officials to help with the data collection. If his request was accepted, he says, the entire census exercise – including the filling of form 2A – would have taken 20 days to complete. But his request was not accepted and the army could spare only 200,000 of its troops for census duties — forcing the PBS to complete the census in two phases, each taking 14 days. Filling out form 2A, even if from a select number of households, would have significantly increased this time, he says. The army was not ready for that.

Bajwa also clarifies that the decision to exclude form 2A in the census data collection was not made by him or by the PBS. It was made by the Council of Common Interests – a constitutional body that includes senior representatives from the federal administration as well as the four provincial governments – that decided that form 2A would be filled seperately at a later date.

Dr Mehtab Karim of the Malir University of Science and Technology remains sceptical of the government’s ability to conduct another survey in the near future. “Sample surveys are very expensive because you have to find the households that match your sample.” It was easier to fill form 2A during the census, he says, since you only needed to collect additional information from every tenth household that you were already visiting.

The other problem with the census, experts point out, is breach of confidentiality. The minute you ask someone to hand over their identity card number and then have a soldier in uniform verify it on site, you have violated a basic census principle, says Karim. Ideally, an enumerator is not required to take down a person’s exact age either. They just need to note that an individual is within a certain age bracket.

It is precisely this verification by soldiers that UNFPA observers have also objected to in their report. Age records were mainly obtained from CNIC data and most often verified by army officers accompanying enumerators through text messages to the National Database and Registration Authority (NADRA), says the report, published in the press on September 24, 2017. This constituted a “breached confidentiality”.

The report is critical of the army’s involvement in the census. It says the army’s participation in the process was “not at all a recommended international practice”. The observers point out that the “data collection by the military… amounts to a parallel census and this is not internationally acceptable.” The army also asked questions about the nationality of the heads of households, the report says. “This is very unusual and questionable especially given the fact that the main [census] questionnaire had no provision for [details about] nationality.”

The advisory committee set up by the PBS had made about a dozen recommendations along similar lines. One of these was the exclusion of the armed forces from the enumeration process. “However, I must admit that, considering the security situation in many areas, I can see why it had to happen,” says Dr Muhammad Iqbal of the University of Peshawar and a member of this committee.

The committee also unsuccessfully recommended that the census be done in one phase — doing it in two phases might have resulted in some people getting counted twice, as Iqbal suggests. Other issues that the committee highlighted concerned the inclusion of Khowar – a language spoken in Chitral – and Sikhs as separate categories. But, as Iqbal says, these recommendations were dropped because there was no space available for them on the already printed census forms.

Another important recommendation by the committee was that showing of CNICs should not have been required for a person or a family to be counted during the census. “It was primarily made mandatory to identify those living illegally in Pakistan,” says Iqbal. “But that is not the job of the census takers.”

His fellow expert on the advisory committee, Karim, is also concerned. Up to 30 per cent of people in Sindh alone do not have CNICs. Hundreds of thousands of other CNICs have been blocked by NADRA on the suspicion that they have been obtained by foreigners. Our concern was that those who do not have CNICs – and many people in Pakistan do not – may be missed by the census takers, says Karim. The 1998 census did not require people to produce their national identity cards in order to be counted.

Bajwa says enumerators were instructed to count everyone regardless of whether they had CNICs or not and whether they were Pakistani citizens or not. But he adds that 99 per cent of the “33 million families” in Pakistan have at least one member who carries a CNIC. “Unless you are a hermit sitting on top of a hill, you will need an identity card” — if for nothing else then at least for interaction with the state.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that you do not need to be a hermit on a hill to not have a CNIC. Mubashar Ali, an enumerator in Sheikhupura district, met a family in a village only 14 kilometres from Sheikhupura city and none of them had a CNIC. “I asked them to show the CNIC of anyone living in the house. They said none of them had one,” he says.

His fellow enumerator, Mohammad Yaseen, takes out a list of 15 households. Not a single person in those households had a CNIC, he says. He recalls requests by many people for help in getting their CNICs made. “They told us that they have visited the NADRA office multiple time but were unsuccessful [in obtaining the cards].”

The national census, just concluded, puts the population of Punjab at about 53 per cent of the total population of the country — only three per cent below what it was in 1981 and 1998 even though, according to a 2012-13 report by the National Institute of Population Studies, births per woman have fallen in the province more rapidly relative to Sindh and Balochistan. The total population of Punjab has gone up by around 36 million – from about 73.6 million to 110 million – since 1998.

Increase in the population of Lahore, Punjab’s capital city, is even more dramatic. The number of people living in Lahore has increased from about 5.1 million in 1998 to 11.1 million in 2017 — going up by 116 per cent. The fact that Karachi’s population since the same year has risen only by less than 60 per cent makes Lahore the fastest growing metropolis in the country even though evidence suggests that there has been a much bigger influx of people into Karachi from different areas – especially from various conflict zones such as Balochistan, Fata and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa – over the last decade and a half.

PBS Chief Asif Bajwa addressed these apparent contradictions while briefing the Senate Committee on Satistics. He argued that earlier (in January 2015), the Punjab government extended the jurisdiction of the Metropolitan Corporation Lahore (to even the rural and peri-urban parts) of Lahore district that were not counted as part of the city in the 1998 census. Today’s population of Lahore, therefore, is not the population of Lahore city alone but of the entire Lahore district. “… A lot of agricultural land has been included in the Lahore metropolitan area,” Bajwa says. If the city’s 1998 boundaries could be revived, he speculated, its population would be around eight million only.

On the other hand, the government in Sindh has excluded some areas of the Karachi division from the jurisdiction of the Karachi Metropolitan Corporation. In the 1998 census, 94.8 per cent of the division’s population was counted as urban; it has now reduced to 92.9 per cent.

Even these considerations (that is, including the people living in its erstwhile rural areas to determine its population growth rate) put growth in Lahore’s population at above 75 per cent since 1998 whereas the population of the entire Karachi division has risen by less than 63 per cent since the same year. This is in spite of the fact that Karachi’s rural areas have experienced an exceptionally high population growth in this time period. In the 1998 census, these rural areas were recorded to have 407,510 people; the number of their residents stands at 1.14 million in 2017 — suggesting a growth rate way above the national average.

Something similar has taken place in Peshawar too. “Urban Peshawar is demarcated only as the cantonment and the old city,” says Iqbal. Numerous suburbs surrounding the city have been designated as rural areas, he says. But, like Bajwa, he points out that it is not the responsibility of census takers and statisticians to set a city’s limits. “It is the government’s job.”

It is precisely these discrepancies in the definition of urbanisation that make Arif Hasan sceptical about the entire census process. “We first changed the definition of ‘urban’ in the 1981 census,” he says. Previously, all those areas where land was mostly used for non-agricultural purposes and where a minimum of 5,000 people lived together in a single settlement were deemed as urban. Census commissioners also had the discretion to consider any area as urban that had ‘urban characteristics’.

The new ‘standardised’ definition marked only those areas as urban which fell under the jurisdiction of a town committee, a municipal committee, a municipal/metropolitan corporation or a cantonment board, regardless of its population density and land use. The change resulted in 54 areas moving from urban to rural in the 1981 census, making it difficult to compare the census results with those of previous censuses conducted in 1961 and 1972.

“So today you have settlements of over a 100,000-150,000 people [that] are not urban because they don’t have an urban governance system,” says Hasan. “… if you bring back the old definition, then more than 50 per cent of Pakistan is urban today.” But only 36 per cent of Pakistan’s population has been officially recognised as urban, according to the recently released census data — just two per cent higher than it was in 1998.

Why does it matter?

“There is a constant fear among rural politicians because urban growth threatens their rural vote bank,” says Hasan.

One of the most significant political outcomes of a census in Pakistan is the delimitation of constituencies in the federal and provincial legislatures. Clause 5 of Article 51 of the Constitution says that seats in the National Assembly shall be allocated to each province, Fata and the federal capital on the basis of their respective populations according to the latest published census data.

It is not confirmed if the total number of contested National Assembly constituencies increases or remains unchanged at 272 after the census has been carried out. If it does not change, the respective regional and provincial shares – Balochistan has 14 National Assembly seats, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa has 35 seats, Punjab has 148 seats, Sindh has 61 seats, Islamabad has two and Fata has 12 – will undergo some adjustments to conform to the census results. An increase in the number of constituencies will require a constitutional amendment; the adjustment in their allocations and boundaries will only need an administrative/executive action by the Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP).

But it is not yet clear if the ECP will be able to adjust the constituencies in time for the general election due in 2018. As per Bajwa, the complete results of the census will only be released by April next year. Election authorities may not have enough time to redraw constituencies – a process that needs about six months to complete – in time for the next polls.

The other equally, if not more, important aspect of the census is its link with national revenue distribution through the NFC award. According to the most recent NFC formula, population is the single largest factor in distributing federally collected taxes among the provinces — with an 82 per cent weightage. The rest – development needs or poverty (10.3 per cent), contribution in collection of federal revenues (five per cent), and the inverse population density or vast thinly-poplated area (2.7 per cent) – did not have even the tiny weightage they now have in earlier NFC awards.

How population has come to dominate revenue sharing offers a peep into the working of the Pakistani state. Before 1971, revenue was distributed between West Pakistan and East Pakistan on the basis of revenue collection — the area that collected more money in taxes got to have a bigger share of that money. This formula favoured West Pakistan and put East Pakistan at a disadvantage even when the latter needed more money considering its larger population and relatively higher economic needs as a less developed part of the country. Post-1971, population became the cornerstone of the NFC formulas since it favoured Punjab, the most populous and the most powerful province in the truncated country.

This puts Pakistan in a league of its own as far as controversies over census are concerned, says Karim. The issue concerning the census in the country is neither ethnicity nor religion – two factors that are extremely important in many other countries, he says – but “in Pakistan [a census has] more to do with the domination of one province over others”. Given his experience of demography locally and in other countries, as well as his association with organisations such as the Pew Research Center in Washington and the United Nations, he has a wealth of information from across the globe to bear upon his analysis. He says censuses in several developing countries are controversial but in places such as India and Ethiopia relative numbers of various religious groups have more political significance than they do in Pakistan.

Early results of the latest census confirm the status quo — that is, the dominance of Punjab over all others. Many experts as well as political parties and civil society activists have dismissed the numbers as doctored or simply inaccurate precisely because of this. “[Census officials] have done a great disservice. All that the census is doing is maintaining the status quo," says Hasan.

Disconnect the census data from electoral politics and it will be less controversial, recommend senior PBS officials as well as the country’s most experienced demographers. Go one step further and delink job quotas and revenue shares from the census and perhaps no one will want to doctor the demographic data (as was widely suspected in the 1991 and 2011 house counts), they say. After the failed house count in 2011, the PBS formally proposed to the Council of Common Interests to do just that, but its suggestions were not accepted.

The PBS has raised the issue several times with senior government officials in the years leading up to the 2017 census. “Delink population figures from National Assembly seats, the NFC Awards, Recruitment Quota … so that ethnic elements may not influence census activities,” reads a 2015 newsletter it published, listing the minutes of a meeting of its governing council at the Prime Minister Secretariat in Islamabad.

Experts both within the government and outside it point to India where seats in the lower house of the parliament, Lok Sabha, have remained constant since 1976 even though there have been massive changes in India’s population as a whole as well as within each of its many states since then. Consequently, a census in India does not get linked to political and electoral representation even though keeping the number of constituencies fixed might have resulted in huge differences in their size in different parts of the country.

A similar development in Pakistan may create a similar result. Freezing the number of seats in the National Assembly may soon lead to under-representation of certain provinces/districts and over-representation of others. That may not be a good bargain in a fragile federal democracy like ours. And it will require a constitutional amendment which may find few takers in a parliament where the move to fix the number of National Assembly seats can easily be seen as yet another attempt by Punjab to maintain its hold on political representation and economic resources of the country.

Change may be a little easier to effect in the NFC’s case.

The parameters for the distribution of revenue between the federation and the provinces are outlined in Article 160 of the Constitution. It states that the NFC must be set up every five years in order to devise a new formula for revenue sharing. This leaves ample space for gradually decreasing the salience of population. This process, in fact, has already started and was set off by the seventh NFC award (announced in 2009) that, for the first time since 1973, came up with a formula that reduced the weightage of population from 100 per cent to 82 per cent in deciding which province should get how much money. Reducing the weightage of population further in the NFC award, which is already overdue, may have the desired effect of a more equitable distribution of revenues.

The authors of a 2006 essay on the NFC awards in Pakistan, Nighat Bilgrami Jaffery and Mahpara Sadaqat, made the same argument. “… the unit cost of provision of services is very high and the share of divisible pool is insufficient to cover it” for a province like Balochistan, they wrote in a journal, Pakistan Economic and Social Review. “Therefore, in order to have equitable distribution of resources it is necessary that backwardness must be given high weight by the national government in the allocation from the divisible pool.”

But democracy and demography are linked. Both are about people – as the first half of the two words suggests – and about numbers. Demographic data will continue to be important as long as we have provinces with unequal number of people living in them with unequal development needs.

Additional reporting by Danyal Adam Khan

This was originally published in the Herald's October 2017 issue. To read more subscribe to the Herald in print.

The writer is a former staffer of the Herald.