If I were asked to describe Musadiq, I would say, “He was a shooting star that rose, shone and disappeared. Shone from the earth to the galaxies.” I never thought I would be thinking about him in the past tense. He was the kind of person who would live in the present and love every moment of it. For who knows what tomorrow may bring. In our tomorrow, Musadiq is not there, but his memory is.

It was the winter of 1986. Students of the Fine Arts Department of the National College of Arts (NCA) in Lahore were returning from their tour of India. At Attari station, they had to wait the entire day for the next train to Lahore under the December sun, without any shade. To kill time, Musadiq started playing his harmonium; another teacher from the NCA joined in with his tablas that he had bought from India. Musadiq started singing a Tufail Niazi song: “Sada Chiryan da Chumba way Babala” (Father, we daughters are like a flock of sparrows).

Like his friends, his interests were vast and varied: he was a keen spectator of Muharram processions and concerts of Royal Albert Hall, alike. He was concerned about the environment; from the coast of Karachi to the fish beneath the Indus Delta.

His voice floated over the whole landscape, rising over the borders. The villagers from either side of the Wagah Border started to throng the iron grille gate. From the Indian side, the villagers brought meals with sarsoon ka saag, lassi, roti and gifts as this impromptu soirée continued. This was Musadiq, my friend, and such was the effect Musadiq’s music produced.

At the time, the country was under the boot of Ziaul Haq’s martial law. Under Zia, Pakistani arts faced severe censorship. “My hands always remained in fists,” was a line in one of Musadiq’s Urdu poems. In a protest by NCA students during the dictatorship, Musadiq lost an eye in an attack by militants of the Jamaat-e-Islami, a pro-Zia religious political party. Generations later, not many NCA graduates may know that it was Musadiq and his comrades who struggled to elevate the NCA’s fine arts diploma to a four-year degree programme (the cartoonist Sabir Nazar, Mudassar Punoo, Tahir Mehdi, New York’s sculptor couple Ruby and Khalil Chishti, and Munawar, who hailed from Bangladesh, were all his contemporaries supporting this cause).

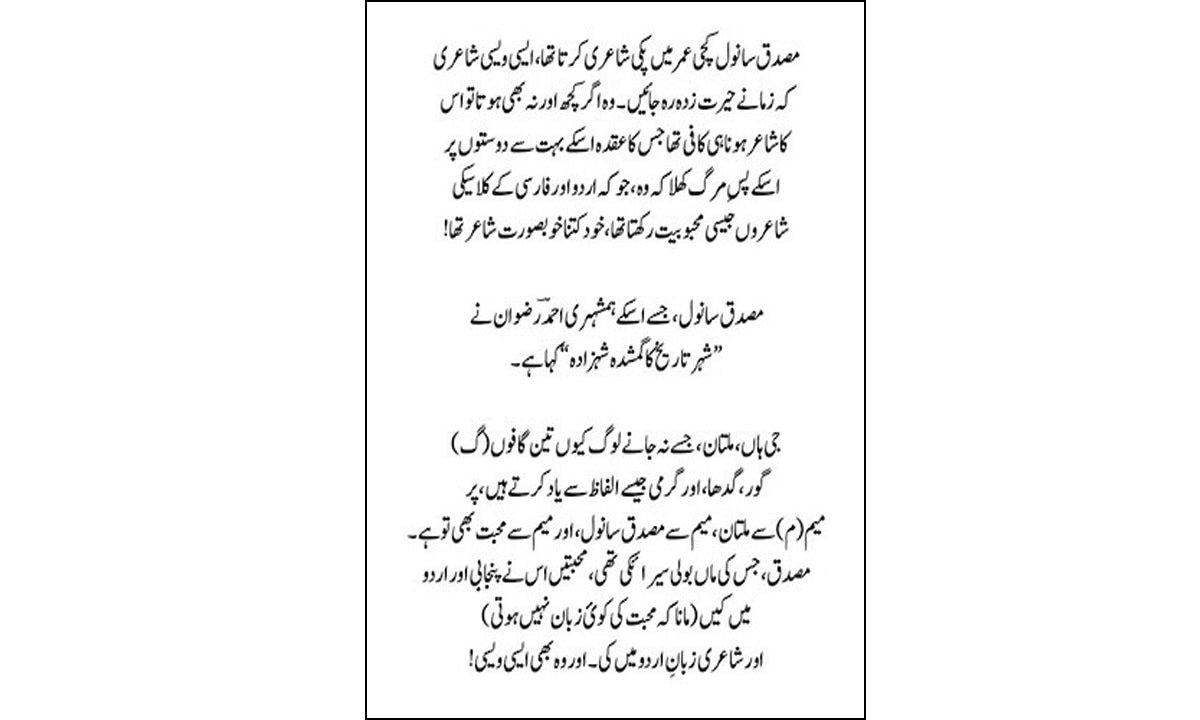

Musadiq himself came to NCA to learn painting but nobody saw him paint. Instead they always heard him singing and playing music. A seasoned Urdu poet even in his young age, he threw away journals of his Urdu poetry as he developed his love for Punjabi classical music as well as Sufi and modern poetry.

Although he wouldn’t have money to eat sometimes, he always wore the finest clothes. “I borrowed a coat from him when I went to meet the parents of the girl who would later become my wife,” a friend from NCA recalls.

He wrote a play that was to be staged in Alhamra Arts Council. The story revolved around a love triangle between a girl, an artist and an owner of a shoe factory. The artist wins the girl over by making a painting of her, while the owner of the shoe factory loses everything for the sake of his love when he gives away all his assets to the artist in order to become a painter. When the girl asks the artist to make her a painting, the artist makes a painting of a shoe, instead.

Soon after this play, Musadiq left Lahore for Karachi. The city was burning with ethnic strife. Post-Zia, the operation against the Muttahida Quami Movement (MQM) was underway. With his tablas, a harmonium and a few pairs of the finest vintage clothes, he ended up at a cousin’s house at Tariq Road. He found work as a copywriter in an advertising company and then at Glamour magazine, where he met Mohammed Hanif, now a prominent novelist. In Hanif’s words, they were known as the “notorious pair”; Musadiq’s tablas were the root of his friendship with Hanif, and his place became a hideout for many other artists such as his wandering friend and great Sindhi poet, Hassan Dars.

In Karachi, Musadiq rose as a star on the theatre scene. Rizwan Ali, a friend of his, who is now a successful psychiatrist at Virginia, recalls: “My friend Ehtesham Shami told me a young man has come from Lahore. Let us meet him. I met him at Café Liberty and was hypnotised by his conversation. Since then, I shadowed him all the time.” Musadiq was all love, theatre, music and poetry. He had the ability to turn his meeting with two or more people into a crowd and indeed a spectacular theatre. With Khalid Ahmed and Sheema Kirmani, he did theatre under Tehrik-e-Niswan. Later, with Rizwan Ali, he directed Jis Ghari Raat Chalay, a play based on a true story of a schizophrenic girl who is raped. His other epic play was Chahanga Manga which was based on the themes of environmental degradation and urban sprawling of Karachi. I wrote jingles for this play which was later retitled as Meenu Say Milnay Ai Kahani.

Musadiq could befriend all, be it a distinguished psychologist from the city or the fisherfolk of Ibrahim Haidery. Like his friends, his interests were vast and varied: he was a keen spectator of Muharram processions and concerts of Royal Albert Hall, alike. He was concerned about the environment, from the coast of Karachi to the fish beneath the Indus Delta. The last time we spoke, he wanted me to write a song on the missing persons which he would compose.

If there were ever a human embodiment of music, love and poetry, it was Musadiq Sanwal. He now sleeps forever beneath the dust of his hometown, Multan. But the piercing eyes and soul of this beautiful Seraiki boy will haunt us all forever.

Hasan Mujtaba is a writer, journalist, poet, song writer and human rights activist. His poetry collection "Koel Shehr ki Katha" was launched in August 2015.