Most of artist Qinza Najm’s works are composed in acrylics on hand-woven wool tapestries. I wondered about the use of the carpet: was it meant to say, ‘brush it under the carpet’ all that must be concealed, or was the carpet used as a metaphor for something else?

“I do mean to say let’s not sweep it under the rug/carpet, but the carpet is also a defining space. I associate it with my grandmother sitting on a carpet to tell me stories,” explains Qinza. As Najm was born in Lahore, the vibrant colours and rich motifs of the carpet along with its dense layers perhaps also provide her with a link to her heritage. When the great Mughal emperor Akbar shifted his capital from Fatehpur Sikri to Lahore, he also established carpet weaving karkhanas (workshops), among other imperial workshops, such as those of miniature paintings. Lahore became the carpet weaving centre of India for almost a hundred years before it lost its prominence as the main capital of Mughal India.

Qinza’s solo show titled ‘And All around Her There Was a Frightening Silence’ and curated by Brooke Lynn McGowan opened in Karachi at Chawkandi Art Gallery on November 15, 2018. Her entire body of work, based on gender, sexuality, gun violence and Islamophobia in equal measures, gives hope and strength, with a feeling of upward momentum and empowerment, which orients her art practice.

Qinza has spent much of her adult life in New York. She pursued her fine arts studies at Bath University and The Art Students League of New York. She has exhibited internationally, including at the Queens Museum (New York City), Christie’s Art (Dubai), Art|Basel (Miami, FL), and the Museum of the Moving Image (New York). Her work has also been featured in many international print media.

After viewing the exhibition, I sat down with the artist to ask her about the “stretch” in nearly all her works. I wondered if it denoted a shaft of light either emanating from the head of her subjects or falling on them from somewhere above to depict wisdom. Qinza clarifies that the elongation or stretch is meant to say: stretch and get out of your current misery. “Tap into your own inner strength and resources, and transform your life’s narrative,” she says.

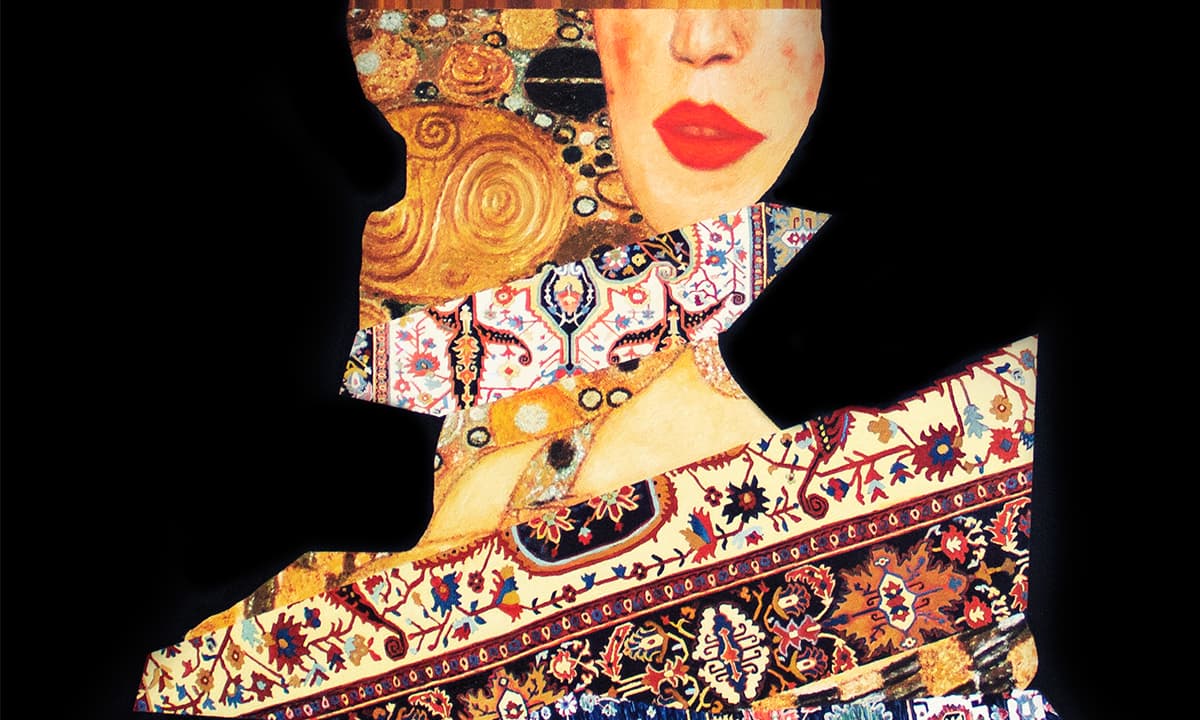

Her Vermeer’s Girl with Persian Rug, Swept Venus, The Picasso Tongue, Klimt’s Lips and other such titles are an attempt to reverse the male gaze by trying to give a voice to those women. Qinza’s work addresses some deep social traumas for which she has been using multimedia, video, painting, performances, etc, to bring forth these concepts. She has a PhD in psychology and this enables her to have a deep perception of the human mind, which is compounded by her artistic manifestations in various mediums for creating understanding and empathy. These perceptions are not only targeted towards the genders but also the East and West societies.

In December 2017, when Donald Trump imposed a ban on residents of six Muslim countries, refusing entry visas to prospective travelers from Chad, Iran, Libya, Somalia, Syria and Yemen, Qinza decided to learn from YouTube to wear a hijab for a performance. “As a family, we had never covered ourselves,” she says, “I therefore needed to perfect my act.” She wore it and boarded a subway in New York City. She was not expecting her act to turn into an ugly incident, but unfortunately it did. Just before she was getting off, a man who was also inside the same carriage, lunged forward, abusing her and trying to snatch the hijab off her face. “I just ran on the platform with all my strength, without daring to look back.” She says it was a while before she realised that the man had not followed her as he was probably inside the moving train.

When The South Asian Women’s Creative Collective (SAWCC) announced its call “to revel in and reveal your own contentious, uplifting, and complex notions of Beauty”, Qinza decided to participate. She had a performance for which she collected around 20 hijabs from around New York City. Almost 800 men, women and children participated, donning the hijabs, taking selfies, looking into mirrors and by and large, figuring out for themselves that a woman in a hijab isn’t someone to be feared or abhorred. “The performance helped create tolerance.”

Her Veil of Bullets is a large 68 x 44 inch metal print in which Qinza is seen sitting with a fishnet over her entire body, pierced with bullets on the part that covers her head. The background is once again a rich, luxurious red carpet. Incidentally, this image was taken from a performance act she did in the US at the Museum of Moving Images. She had collected 1,100 empty bullet casings from different shooting ranges from around New York City and pierced the eleven yards of fish net – her veil – with hundreds of those spent bullets. “We are trapped in violence,” she says. The audience was invited to carry the heavy weight of these empty bullets, but the more people carried the veil the lighter the weight of the bullets became. “In 2016, 1,100 women were killed in Pakistan in ‘honour killings’ and some 1,100 American children have been killed in the US in shootings that have mostly occurred in schools,” explains Qiza.

Her charpoy video installation is most engaging. She requested female narrators to bring any one object that symbolises violence in their lives and another one connected to the healing process. The stories of resilience shared by them in the video are projected on a white sheet thrown across the humble cot. They are journeys of immense pain and vulnerability, which have been overcome by determination and accomplishments, and the endeavors of these women have led to their empowerment.

The writer is the author of Karachiwala: A Subcontinent Within a City. She tweets @husain_rumana