Raindrops fall from the sky on bare winter trees, their branches spread in the manner of a person wailing with arms spread out. The golden beams of a sun filtering through clouds turn these droplets into prisms that throw up curious combinations of emerald, green and turquoise. Another array of raindrops gleams like small mirrors, suspended to bare boughs running from one end to the other.

This is not a scene from a mountain valley coming back to life after heavy snows. It is not even the creation of a writer’s fertile imagination. It is part of the fantastical imagery often found painted on trucks plying across Pakistan. Be fascinated by it and call it truck art. Be detached and you will see it as mere decoration. For a truck driver, it is the make-up of his “bride”.

In the metamorphosis of a truck into a bride, the body parts of the vehicle assume human aspects. The silver, metallic decoration on top of the driving cabin is a taj, a crown; the windscreen is matha, the forehead; and the bonnet is hont or lips. The lowest part of a truck’s front – where the bonnet meets the chassis and tyres – is adorned with golden metal bells, ghunghroos, hanging by a series of vertical steel chains.

The 50 or so bells chime and dance as an elusive film melody plays in the distance on an early February day at a Rawalpindi trucking station, known as adda in transport diction. “I have strung these bells together myself,” says Ghulam Munawwar, a 40-something truck driver, as he points towards the vehicle he calls his bride. “Her splendour lies in these details,” he says with eyes beaming in admiration. “Isn’t she beautiful?”

The part of Pir Wadhai Road where the adda is located is witnessing an interesting tableau in the skies. A meek sun trying to peer through a canvas of rain-laden clouds is turning them purple at the edges, giving them wondrous shapes and hues — similar to the ones you see in landscapes painted on trucks.

Here is a sample: a strange two-headed fish made with glowing sticker tape in bright hues of red, green and yellow swims in an ocean of windshield glass. The outer surfaces of the carriage behind the engine are crammed with thick foliage surrounding a crisp blue lake glistening under the sun; a fish soars to the skies; a peacock walks dreamily around a tree in the company of exotic birds peering from a window; a benign-looking serpent rests under the watchful eye of a tiger. This Garden of Eden could not have been complete without the woman painted on the back of the truck. Looking into the distance with her head covered, she looks like a heavenly beauty uncorrupted by satanic designs.

Who is she: a politician, a film actress, a freedom fighter or the quintessential representation of unblemished female charm? Munawwar does not have a clue.

The driver swiftly climbs into the truck to avoid the drizzle that has just started. The interior of his driver’s cabin is trying its best to compete with the overly decorated exterior: beads, artificial flowers, imitation necklaces and a rosary jostle for attention along with colourful drapery, lights, mirrors and the portrait of a heavily bearded saint dressed in yellow and green.

Munawwar puts the key in the ignition. His assistant, the kleender (possibly a distorted form of the English word ‘cleaner’), hops into the truck from the other side as the vehicle begins to amble on to the G T Road.

The road sometimes seems to be passing through a veritable truck land, especially in the mountainous regions of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and northern parts of Punjab: houses and natural environs closely resemble the idyllic scenes depicted on trucks. Almost every driver in the country passes through these mountains and valleys multiple times during his career. Many even have their homes and villages there. Their personal and emotional attachment to these parts is not surprising. Do the motifs painted on their vehicles represent this personal link?

A middle-aged truck driver near Lahore quickly dismisses suggestions that anything in the scenery painted on trucks is a nostalgic – and thus romanticised – version of a driver’s home, birthplace or some other venue stuck in his memory. “It is not the reality of our houses or our lives,” he says, “it is our hopes that we paint on trucks.”

This resonates with Durriya Kazi, head of the visual arts department at the Karachi University. The layered complexity of the visual language on trucks is symptomatic of the diverse thoughts, ideas, dreams and ideals truck drivers and owners have, she says. The images painted on trucks, according to her, are a “hyper reality” that we all live in our imagination.

It is still midday in Dera Ghazi Khan. Yousuf Zahoor’s phone rings. He pulls it out of his pocket – a basic handset held together with a rubber band – and cancels the call. “Time, it cannot be wasted,” he says as if to himself.

Famed for making portraits that sit on the back of thousands of trucks across Pakistan, Zahoor charges 600 rupees for each portrait he paints. Every minute equates money for him — money made or money lost.

His job is made easy and quick by the nature of his work. Each portrait seems to have the same basic structure to which a face is then attached — identification depends not on the exact portrayal of the features but on the dress and other paraphernalia.

At first glance, Rehman Dakait, a Lyari gangster he paints, may almost look like Jalal Chandio, a Sindhi folk singer — but for his sun glasses and black shalwar kameez. Chandio is always made distinct by showing him in a white dress and Sindhi cap.

A tribal elder, a political leader or a dead Baloch nationalist looks different from the chief of the army staff or cricketer Shahid Afridi only due to their varying headgears, clothing or other signs specific to their fields of life. A Kurdish rebel, a Palestinian freedom fighter, an Afghan war hero, Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, General Ayub Khan — everyone has the same plump round face and big bright eyes. Benazir Bhutto, Princess Diana and film actor Nargis mix and merge in confusing succession as they appear on the backs of trucks moving on Pakistani highways.

Once the portrait is completed, Zahoor hops off the truck without signing his name on it. “He stopped signing his work a long time ago,” says Abdul Wahab, the driver of the truck being painted. He then playfully says it could be because the last time the painter put his signature to a portrait, he was taken away by the late Nawab Akbar Bugti’s men.

An audience gathers as the story begins. The year was 1994; two jeeps stopped outside the adda where Zahoor was working. A group of men with guns slung across their shoulders walked around, asking for him. They had orders from their tribe’s leader to take the artist to Dera Bugti, their native town in Balochistan. Zahoor is said to have told them that he would leave with them only after completing the portrait he was working on. The men waited. They would not disclose why they had come all the way to take him away. Zahoor then travelled 325 kilometres with them and was presented to Bugti.

The tribal chief warmly embraced Zahoor, appreciating a portrait of himself that he had seen recently behind a truck painted by the artist. He got Zahoor to paint his portrait — showing him standing next to his son, Salal Bugti, who was murdered a couple of years earlier. The artist stayed in Dera Bugti for many days and was safely returned to Dera Ghazi Khan once his work was finished.

Zahoor smiles, his white teeth glistening against the stark black dye of his moustache, when asked if that was the reason for not signing his work. “Artists sign their work. This is not art. This is a potboiler.”

He also does not want his children to follow in his footsteps. “No, I want my children to study. Truck painting is an uneducated man’s job.” People take up this profession not out of choice but out of necessity, he says.

As a 12-year-old, R M Naeem, too, started painting trucks out of necessity. Now working as an assistant professor at the National College of Arts (NCA), Lahore, he had to paint signboards for films and shops, and work with truck painters in his native Mirpur Khas town in Sindh to fund his schooling.

“Truck decoration is not stagnating; it is dead,” he tells the Herald in an interview. This is because truck painters treat their work as a source of livelihood. They do not have the time or the luxury to innovate; they repeat the same old patterns, images and icons over and over again, he explains.

Naeem attributes this state of affairs to the lack of appreciation by the state as well as society, and the absence of incentives for artistic innovation. The art circles and the cultural elite, according to him, do not treat truck painters as artists, but rather as artisans. Without suitable incentives, these painters will not feel the need to create something new or to transfer their learning to younger members of their families, Naeem laments.

Surrounded by mango orchards, his birthplace, Mirpur Khas, is located on the north-western tip of the Thar desert — on the confluence of Sindh and Rajasthan. The town has been a melting pot of regional and religious influences since at least Partition when it received a big influx of migrants from the other side of the border. Thari, Sindhi and Rajasthani artistic and cultural traditions mix here curiously with Muslim and Hindu ones.

About three decades ago, Mirpur Khas was a bustling centre of truck painting and decoration. Some vestiges of that still exist.

Also read: Three wheeled canvases — Hazara's rickshaw art

The smell of turpentine inundates the air as spray painters in the town’s bus stand use a pressure gun to colour the base of a van. Just behind them, calligraphy is being done on a tractor. The calligrapher’s name is Syed Wajid Ali Shah. Quite like his namesake, the last ruler of Awadh, he seems to be presiding over a decaying art enterprise. “Mirpur Khas used to have all these big truck painters but most of them have left town,” says Shah.

Among those who have migrated was one Syed Jameel who taught Naeem how to paint text, a technique that still forms a major part of the latter’s work. Those who stayed back have been forced to use tractors, vans and buses as their canvases. Even that work has shifted – mostly – to the nearby town of Tando Allahyar.

Since Shah is working with words, one assumes he can also read. He, in fact, is illiterate and paints words as shapes and images — creating replicas of letters as he sees them. It does not matter to him if the text is in Urdu, English, Arabic or some other language.

In a nutshell, this explains why truck painters stop short of becoming fine artists and why their work does not graduate to become art. While they faithfully reproduce the aesthetic aspect of an object – a face, a forest or a flower – they do it in a mechanical way. Their work lacks imagination.

Naeem believes their artistic illiteracy is the result of a certain mindset among the elite that wants to deliberately keep these painters as artisans – as executors of someone else’s ideas – rather than letting them become artists. “The British turned us all into craftsmen,” he says, referring unwittingly to the NCA which was established by the British colonisers in the second part of the 19th century as a school to train craftsmen and artisans in indigenous arts and architecture. Naeem believes the elite perpetuates the same attitude today. “They do not want people to become thinking artists because once you think, you question.”

Herein lies an explanation for Naeem’s own evolution as an artist. He managed to rise above the ranks of signboard and truck painters only after he was admitted to the NCA — that is, by joining the cultural elite and by proving that he can think as well as he can paint.

The loose structure of these saintly narratives also makes them prevalent – if not entirely acceptable – in all parts of the country and among different sections of the society. Trucking, as will be argued later, thrives on this kind of universal recognition.

Haider Ali, a Karachi-based artist in his late thirties, has taken a different route to graduate out of being a truck painter. He learnt truck painting from his father, Mohammad Sardar, starting at the age of seven; he has worked in Karachi’s Garden area, known as the hub of truck painting, for more than two decades. Even as a truck painter, he says, it was his ability to innovate that made his colleagues refer to him as an ustad at a young age.

Ali is one of the first truck painters to use his skills on surfaces other than vehicles – he has been painting peacock and flower patterns on lamps, water pots, photo frames and tea coasters since the early 2000s. One of his early works is a wheelbarrow that adorns the ground floor hall at The Second Floor (T2F), a popular restaurant and community space in Karachi, founded by the late Sabeen Mahmud. For his latest project, Ali paints bridges, flyovers and other public spaces as part of a civil society initiative called I Am Karachi.

Ali, whose works have helped truck paintings enter the home space, agrees with Naeem that art is a luxury that needs to be “befriended and seen beyond bread and butter”. He signs his work as Truck Artist Haider Ali —thanks to some lucrative assignments, he seems to have acquired that luxury.

Anjum Rana, a Karachi-based art entrepreneur, has set up an organisation, Tribal Truck Art, with the self-declared mission to help other truck painters become free of financial worries. According to her organisation’s website, she “has made it her goal to bring [truck] art into the mainstream, into our homes, and give it the recognition it so richly deserves.”

Rana employs truck painters for decorating lamps, lanterns, mugs, kettles, trays, boxes, watering cans and buckets. Those painters, thus, get a new source of income as well as “a new legitimacy” for their work.

Naeem, however, does not endorse this model for promoting truck painting and improving the living conditions of its practitioners. “What is happening is that the privileged classes are hijacking these traditional crafts as their intellectual property,” he says, by creating a hierarchy in which design managers and marketeers stay above those creating those crafts.

He is opposed to the very idea of outsiders telling truck painters what to do to survive. This very rescue mentality is wrong, he says. That the members of a privileged class ascertain what should be painted and where it should be sold, he says, is ridiculous.

Jamal Elias, chairperson of the department of religious studies at the University of Pennsylvania and the author of On Wings of Diesel: Trucks, Identity and Culture in Pakistan, says there is a reason why the privileged class would want to patronise the under-privileged. The absence of interaction between the two classes leads to a lack of understanding among the former about the working of trucking economy, he says. The only bit of culture attached to this economy they observe and react to is a truck’s most striking aspect — its visual imagery.

The sun beats down upon Zahoor’s brow as he cranes sideways to have a look at a large canvas. A whitewashed background with an elaborate border of floral collage made of intricately cut florescent stickers is what he sees. Dipping his big, flat brush in green paint, he starts making broad strokes as spectators watch. A red, a brown, a peach, a green — colours start spreading across the canvas in this very order.

The adda starts buzzing with admiration as his work progresses. “Zahoor is a computer,” says Wahab, the driver. “The pictures he paints are embedded in his mind.”

He is painting a figure – seemingly an androgynous one, at least initially – but as Zahoor adds one layer of colour over the other, the contours of a male face start appearing. One broad, bold stroke, then another and another — he goes through the motions he has perfected through countless repetitions. He squats swiftly as he mixes petrol with paint. (Petrol helps the work dry faster. The other option is kerosene oil which takes longer to dry and also has a smell that stays longer in the air compared to that of petrol.) His apprentice, a young boy with the hint of a moustache, puts glitter on the painted figure. Soon enough the portrait is complete.

All it takes is 60 minutes.

A truck is made in three phases and involves at least 13 crafts. The main frame is made by the welder (lohar), metalworker (show wala) and the denter (local word for a person who irons out dents ); engine work is done by the mechanic (mistri) and the electrician (bijli wala); the base colour is given by the spray painter (rang saaz), and the calligrapher (likhai wala) writes poetry and other texts. Specialists of glasswork, metalwork and woodwork further adorn the vehicle – each with their own craft; chammak patti wala and the plastic wala, respectively, work with reflective tape work and decorations made of plastic. Seats are made by the upholster (poshish maker) who also decorates the truck’s interior with beadwork and other hangings. The trucking world appears inhabited by a diverse group of specialists, brought together by a common cultural and commercial endeavour.

The town of Dera Ghazi Khan, around 500 kilometres southwest of Lahore, is renowned for producing some of these specialists. Next to a busy crossing – known as Samina Chowk – on the entrance to the town from Multan, are multiple addas where some of these artisans work. Manzoor Hussain is one of them.

Everyone here calls him Ustad Manzoor Chamak Patti Wala after the work he does: producing decorations made from colourful fluorescent tape. His workshop looks like a small rudimentary hangar — open from the front but enclosed from three sides. Inside the dusty grey brick building, Ustad Manzoor sits on a straw mat laid out on the uneven ground, mechanically producing chamak patti at a brisk pace.

He says every design he is making is done exactly how it was taught to him by his teacher. “It is all memorised and is in my mind,” he says, echoing what onlookers state about Zahoor’s production process. No imaginative rethinking of designs takes place here; there is no room for any artistic innovation.

Computerised printing has reduced the importance of even memory and the long and hard mentoring that Ustad Manzoor underwent. Printers in Karachi produce more chamak patti by pressing a computer key than Hussain and his three apprentices do in a whole day — and all with the pre-set designs.

A narrow road in the city’s Garden East area, with cars parked bumper to bumper on one side of it, is where many of these printers, including Asif Awan, do their business. He copies chamak patti patterns from the internet and prints them on fluorescent sticker sheet without even looking at them carefully. The most popular designs are pasted on the door of his shop — Che Guvera wearing a hat with the symbol of a Baloch nationalist group on it catches one’s eye immediately.

Awan makes small alterations of this type on request from his customers. Otherwise, his production process is simple — copy, paste and print. Why does he not create original images? “We make what the truckers want. Why put in extra effort?” he responds.

It is true. Trucks are painted mostly the way their drivers like.

Religious emblems and portraits of saints make an essential part of the images and icons painted on trucks. Syed Abdul Qadir Jilani, a revered 12th century Sufi, is perhaps the most ubiquitous religious figure on the trucks.

A direct descendant of the Prophet of Islam, he spent most of his adult life in Baghdad, now in Iraq. He is remembered by several different names among his devotees in the subcontinent – Ghaus Pak, Ghaus-al-Azam, Gyarhveen Wali Sarkar and Yarhveen Wala (the latter two associating him with the 11th day of every Islamic month which is regarded his day by his followers). He is believed to be the source of several miraculous legends. One of them goes like this:

Once a wedding procession was crossing the Tigris River near Baghdad on a boat. Suddenly a high wave turned the boat upside down. When the bride waiting on the other side of the river heard about the accident, she was heartbroken. In her moment of helplessness, she is said to have approached Jilani for help, urging him to save the wedding procession. The saint accepted her request and raised his right hand in the air as if he was lifting something on his palm. Soon the boat was sailing again on the Tigris as if someone had lifted it up from the depths of the river.

For truck driver Allah Tawakkul, and almost everyone in his profession, Jilani is Yaari Baba, the saint of companionship, who helps wayfarers as he had helped the drowned wedding procession. “Yaari Baba will take care of us as we go on our long journeys,” Tawakkul says while standing under a fluorescent tape portrait of the saint at a roadside food stall on G T Road near Jhelum.

A few days later in Multan, the Sufi legend takes a different turn. Driving through the narrow lanes of a bustling part of the city, a rickshaw driver stops at what looks like a shrine. A hoarding carrying the image of a woman praying next to a boat on the river and an elderly bearded man in a turban graces the entrance. This is the tomb of Musa Pak Shaheed, a 16th century Sufi, whose successors include former prime minister Yousuf Raza Gilani.

Shaheed is a descendent of Jilani (Gilani being a variation of it). A caretaker at the tomb insists that the Sufi buried there had also saved a boat in the same manner his famous ancestor from Baghdad had done.

Meeran Mauj Darya Bokhari, another saint buried in another part of Multan, is also credited to have performed the same miracle, as have a number of other saints and Sufis whose tombs and shrines can be found in every part of the country. Nobody quite knows how and why a single legend could be attributable to several people at the same time. What is certain is that travelling has always been a hazardous undertaking – it remains so even now in spite of all the technological developments – and travellers have always required some kind of special protection. Sufis and saints have been very helpful in this regard.

There is also another explanation: travel is a metaphor for overcoming the limitations of time and space. As travellers break these boundaries so do their patron saints. Taking different names and assuming different identities, these Sufis transcend both centuries and cities, and become available for help to their followers wherever and whenever they are required.

The loose structure of these saintly narratives also makes them prevalent – if not entirely acceptable – in all parts of the country and among different sections of the society. Trucking, as will be argued later, thrives on this kind of universal recognition.

The portrait that Zahoor has painted on Wahab’s truck is of Jalal Chandio though the driver is not even familiar with his music. Why, then, is he getting him painted on his truck? Wahab laughs heartily as he explains that Chandio’s portrait is his licence to move easily through police checkpoints while passing through Sindh — a route he frequently takes. “The police don’t stop you; they don’t issue you a challan (ticket) because they think you are a Sindhi.”

While deciding how to get their trucks painted, drivers are motivated as much by their likes and dislikes as they are by the prospects of having smooth trips in various and diverse parts of the country. That explains the eclectic imagery and icons that one finds on the body of a truck. The truck that Wahab drives to Quetta, for instance, has Balochistan’s Chief Minister Sanaullah Zehri painted on the back of it for the same reason.

Wahab, indeed, is the epitome of multiculturalism reflected in the world of Pakistani trucking. He was born in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa to Pakhtun parents but now lives and works in Karachi, and he speaks Sindhi fluently. Geographical divisions are porous in his universe if and when they exist – and matter – at all.

Wahab says even insiders of the trucking business cannot tell where a truck belongs from the images and portraits it carries. The number plate may give a clue but sometimes even that does not since a Punjabi truck owner might have had his truck registered in Lasbella, Balochistan. “Trucks do not belong to one city. They never can.”

A man stands next to his sugarcane juice cart in the midst of a line of trucks. This is one of the largest trucking stations alongside Peshawar’s Ring Road — a highway that skirts the city on three sides like a ring. The cart is covered with images of valleys, eagles, a lion and a pair of female eyes — a miniature version of an elaborately painted truck.

Across the road from the juice vendor, truck driver Waheedullah sits on a charpoy. He speaks with easy affability. “Lowari Pass is the road to hell. It is by far the most challenging route,” he says.

Located at a height of 3,118 metres, the pass is the only route connecting Chiltral valley in the north-western part of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa with the rest of the province. A truck, made heavier by all its embellishing crowns, hangings and painted panels, will always struggle to manoeuvre through its steep and narrow paths.

Other than hampering the movement of a truck, these decorations may even create risks. According to Elias, these are not permitted by police regulations because of being safety hazards, especially during dangerous drives through places such as the Lowari Pass. This, he says, means that “the decorated truck is, by definition, outside the law.”

Why do truckers invest in illegal ornamentations that easily set their finances back by 300,000 rupees – almost one third of the total price of a vehicle? “Because the better the truck’s appearance, the better the services provided by it and the more reliable it is,” Elias explains. A well-decorated truck gives the customers the impression that it is well taken care of and will, therefore, be a dependable way to transport goods.

As hinted earlier, how big a part decorations have in ensuring the safe passage of the goods is severely tested during the 300-kilomtere journey between Peshawar and Chitral. When asked what preparations Waheedullah makes before travelling between the two places, he says something in Pashto. “Niswar and charas,” interjects an interlocutor only half in jest, mentioning an intoxicant made from minced tobacco and another one processed from cannabis. It is certainly not the reply that the driver has given but, judging by his smile, there seems to be some element of truth in it.

Waheeedullah climbs onto the truck as he gets ready to leave Peshawar. When he opens the door to the driver’s cabin, images of female film actors can be seen stuck inside. Being in such pleasant company could be another distraction he requires to undertake the perilous journeys such as the one to Chitral.

Kausar Baba Nickelwala, an old man wearing a Chitrali woolen cap to keep himself warm on a late winter day in 2016, became a truck decorator nearly forty years ago. By most accounts in Rawalpindi, including that of his own, he pioneered souvenir trucks.

Twenty years ago, an American tourist approached him at his workshop near the Railway Carriage Factory in Rawalpindi and asked him to build a truck that the visitor could take back home to the United States. Nickelwala laughed at the idea first. “The truck will have to be a miniature one if you want to take it all the way to America,” is what he told the tourist. “So build me a miniature truck then,” responded the American.

He gave Nickelwala two months to do the job and asked for the price. The decorator thought he could turn the request down by asking an impossible price and quoted 35,000 rupees. The American returned the next day with the money in his hand.

Also read: What is Pakistani art?

Nickelwala spent the next eight weeks building the miniature truck — with a metal body, tiny tyres, tiny bonnet and a tinier series of bells hanging with steel chains. Painting the truck was the most difficult part. He had to reduce the scale multiple times to arrive at the minuscule level that fit the small truck.

The American, however, did not return. Six months later, another visiting foreigner spotted the small truck in Nickelwala’s workshop and insisted on buying it. He was willing to pay 10,000 rupees for it. Nickelwala did not want to sell something that someone had already paid for but then gave in to the request.

His conscience, however, started giving him worries. What if the first foreigner came back to receive his order? Another truck should be built for him, Nickelwala thought. Now that he was familiar with the technique, he managed to complete two small trucks in just fifteen days. He claims to be safely keeping them both for his original customer even today, refusing to sell them at any price.

Soon the news of his new product began to spread and he started receiving a barrage of orders. While his first miniature trucks were made for the foreigners, in recent years a local market has also emerged and so have many artisans, decorators and painters producing miniature trucks and similar decoration pieces in truck painting style. They sell their wares to non-government organisations working in the fields of arts and culture and for-profit companies that trade in local arts and crafts.

The subcontinent possesses a rich tradition of transport decorations going back many centuries: river boats have always had carvings; artefacts adorned seafaring ships; horses had hennaed foreheads, sometimes even braided and styled manes; horse-drawn carriages were full of wooden designs and printed shades and seats. Even camels had their body hair cut in stylish patterns. It is an obvious and easy extrapolation that this tradition has continued with the introduction of modern engine-based vehicles.

The first Bedford trucks were imported in the subcontinent in the 1930s. “These trucks were simply painted with a protective coat of one colour,” recalls Haji Habibur Rehman, one of the oldest truck painters in Rawalpindi. He is a disciple of Ustad Mohammad Azam and Ustad Mohammad Yaseen – both known as the pioneers of truck painting in this part of the world. The only things painted on the early trucks were the names of the companies they belonged to and their contact details, he says. At the most, a ribbon running across the windshield carried a prayer for a safe journey and a couplet adorned the back of the truck, Rehman says.

Kazi, the Karachi University professor, offers a different version of the history of truck painting. This could be because she mostly focuses on Karachi and its nearby areas such as Mirpur Khas.

Sitting on a sofa in her living room, she explains how the partition of the subcontinent in 1947 altered social hierarchies and restructured power at the political, economic and social levels. With flowers and partridges depicted in the traditional truck painting style hanging on the walls of the room amid other art works, she explains how the partition-related upheavals have had a major impact on the cultural evolution of the areas we now call Pakistan.

For one, Kazi says, many Muslim artisans and artists who used to work at the palaces of Indian princes and rajas migrated to the newly-created state of Pakistan. Most, if not all, of them did not find any moneyed patrons in their adopted country and became available for work that catered to the uneducated masses — truck decorations being one of them.

A pioneer of truck painting in Karachi, according to Kazi, was one Haji Hussain. He hailed from Bhuj area in Kutch district of what is now the Indian state of Gujarat and belonged to a family of painters who decorated the interiors of courts and princely residences. After Partition, Hussain moved to Karachi with his skill set of painting ceilings and murals and was encouraged to turn to decorating trucks by a local artist, Ghaffar Sindhi, who then worked on embellishing horse carriages. Suddenly, crafts that were previously the exclusive privilege of the ruling class to enjoy became accessible to the working classes, Kazi says.

The images that started appearing on trucks were, thus, the variations of what artisans and artists such as Hussain had been painting within the royal palaces of their erstwhile benefactors. Verses, hunting scenes, idyllic landscapes and exotic birds, such as peacocks, painted on the high walls of the elite’s abodes became visible to everyone through this transfer to trucks, Kazi adds.

Initial truck decorations, according to her, consisted of “images of birds, flower vases [and] a telephone with a woman’s hand picking up the receiver on which the [trucking] company’s telephone number would be written”. Gradually, these vehicular decorations developed into an absorber of all relocated skills. A truck became the meeting ground of various regional crafts: its wooden doors carried Kashmiri carvings and an artisan from Gujarat painted its murals. This eclectic nature of truck decorations persists despite several changes in the mix — now the wood carving could be done in Chiniot and murals could have been painted in Dera Ghazi Khan.

All this was expedited by political developments. With the advent of Ayub Khan’s rule in 1958, Pakistan’s truck industry grew rapidly, Kazi writes in her research paper, Decorated Trucks of Pakistan. The military ruler is said to have encouraged many senior army officials to become dealers for Bedford trucks and establish their own fleets. With such a boom in the goods transport business, decorative devices, too, became elaborate.

It was around the same time that renowned Pakistani painter Saeed Akhtar roamed the corridors of Rawalpindi’s Army mess – known as the Pindi Club – as a 16-year-old. “I had come all the way from Quetta in the hope to show Petman Sahab some of my drawings,” Akhtar says.

Hal Bevan Petman, a portrait painter of British origin, usually sat under a tree at the entrance to the Pindi Club those days. He was known for the portraits he had made of India’s ruling elite. After Partition, he decided to stay on in Pakistan and looked towards the army for patronage. He was commissioned to paint war scenes and portraits of generals and important political figures for display in army cantonments across the country: one of the largest collection of his works is on display at the Military’s Command and Staff College in Quetta.

During the summer time in the 1950s and 1960s, Petman would also sit at the Mall Road in Murree, narrates Romano Karim Yusuf, a researcher who is chronicling the painter’s life and works. There, he would make portraits of the “fur -clad elite” visiting the town on vacation.

It is easy to speculate that some of the then serving and former military officers, who had become the owners of trucking companies, were also aware of Petman’s work. Yusuf links a few dots when he says that the army first saw – and used – trucks as a mobile medium for propaganda during the 1965 war. Portraits of Ayub Khan and images of tanks and warplanes began to grace these vehicles along with patriotic slogans and verses during and after that year, he says.

Petman, however, has little relevance to the decision to use trucks for war propaganda. Yet he seems to have influenced – albeit indirectly – how the two generations of truck painters have operated since then. Some in style and technique; others in professional approach and attitude.

Akhtar remembers learning to draw the human eye from Petman. “I have not forgotten those lessons and I still draw the eye like that,” says the artist. Petman Girls, a documentary Yusuf has made on the women who had their portraits done by Petman, makes it amply clear that the painter had a distinct style of painting the eyes as well as the mouth that added glamour to the faces he drew.

One of the women in the documentary says that when she saw her portrait – painted in 1964 at the Sind Club in Karachi – “it seemed to me something out of a magazine that wasn’t quite real. It was like when you are projecting an image of something. I felt it wasn’t me.”

This is exactly what truck painters do: they always draw a version of their subjects that, in fact, is a projection of the image they have in their minds, instilled through years of practising the same lines and strokes over and over again. And it is always quite distant from reality.

Elias says there is no proof that Petman ever painted a truck. But it is possible that his works became the point of reference for the style adopted by truck painters, he tells the Herald in an email interview. Petman did paint Ayub Khan, Aziz Bhatti and many other military commanders from the pre-1965 period. It is highly likely that truck painters used these paintings as reference images when they started painting military-related imagery on the trucks in the wake of the 1965 war.

Karachi-based art critic Marjorie Hussain also acknowledges Petman’s role in the evolution of truck painting. She says truck painters have the same approach – if not the same style and technique – towards portrait making that Petman had: of approaching design as commissioned work, one that is a means of earning one’s livelihood and one that does not particularly need innovation.

Entering the gallery space never appealed to Petman. That explains why he is missing from Pakistani art discourse even though he mentored the likes of pre-Partition Lahore-based artist Amrita Sher Gill. This could be another link: the debate about whether truck painting is an art or a craft emerged only after this type of work entered the gallery space.

Hussain also points out that ‘truck art’ is a recently coined term. Around the early 1990s, truck paintings became the cultural export from Pakistan which the international, and consequently the national, markets started fetishising, she explains. Before that, these paintings were always referred to as truck decorations, she says.

Could it be that truck decorations started gaining eminence after those who could pay for them became interested in them? The answer is straightforward: vehicular decorations take on the form of Pakistani truck art when they exit the domain of truckers and enter the realm where ‘art’ is appreciated, sold and purchased. Whether these decorations are art or not, thus, depends on who is consuming them and who their audience is.

According to Hussain, one of the first attempts to bring automotive decoration to an art-purchasing audience was made in 1985 when artist Laila Shahzada exhibited the works of truck painters at the Pakistan American Cultural Centre (PACC) in Karachi. Hussain was PACC’s director of cultural programmes at the time and recalls how foreigners living in Pakistan took an immediate liking to the works on display. To many of them, these resembled the “gypsy caravan art” of Europe, she says.

More than a decade later, in 1996, artists Kazi, David Alesworth, Iftikhar Dadi and Elizabeth Dadi were invited to take part in an exhibition in Copenhagen, Denmark. The objective of the exhibition, titled Copenhagen 96, was to celebrate the status of this port city as a global centre of trade.

Artists participating in the exhibition from different countries were given shipping containers to use as their canvases. For Kazi and other artists working with her, the idea of showcasing truck paintings in the container allotted to them seemed very apt since it represented transport and trade as well as Pakistan.

This exhibition, notes Elias, was the “first instance in which professional truck painters whose work was incorporated into the finished collaborative piece of art were recognised as artists.” Their names were mentioned along with their speciality; there was Mairaj Nicklewala and sons, Bachoo Painter and Sarfaraz Electrician amongst others.

In Kazi’s own point of view, the reason why they were recognised as artists does not apply to every truck painter and decorator. She believes there is a distinction between an artisan and an ustad: the former is a craftsman who does not innovate but works according to the instructions given to him, obeying the guidelines set for him; the latter creates the idea and devises instructions and guidelines to execute it.

Then in 2002, Ustad Jamiluddin, a Karachi-based truck painter, working in collaboration with Haider Ali, painted a truck that was displayed at the Smithsonian museum in the American capital, Washington DC. That was the first time truck painters produced something completely on their own for display in a gallery space. Such national and international exposure is inspiring a whole crop of truck painters who aspire to follow in the footsteps of Ali and Jamiluddin.

Sherdad, a young man with a paan-stained smile, was a kleender with a truck before he learnt truck painting from a friend during free time. After months of practising motifs on the walls of his bedroom, he made the career transition, seeing it as the only possible opportunity for upward social and economic mobility. “I want to be like Ustad Haider Ali,” he says as he paints flower motifs beneath the Jinnah Hospital Flyover under the watchful eye of his mentor.

So you were on the G T Road after sunset?” wonders Mohammad Ajmal, white mist exiting his mouth as he speaks. “There has been a robbery of goods worth 900,000 rupees near Rahim Yar Khan just a few hours ago.”

In the previous fifteen days alone there have been as many robberies of this kind, he says. Yet the concept of insuring goods for in-country transportation is unheard of. As is security for the trucks and their drivers.

The weather is unusually cold for this mid-February night and, draped in a camel-brown shawl that carefully covers his head and ears, Ajmal appears like a ghost. As the caretaker of Riaz Truck Parking Stand, he has a job to perform — to protect the trucks and drivers from thieves and robbers as they rest for the night in Lahore.

Living conditions are basic at Riaz Truck Parking Stand – located on the Link Ravi Road, across from Sabzi Mandi, Lahore’s fruit and vegetable wholesale market in Badami Bagh area. The tired truck drivers, however, are looking for an affordable place to lie down after a long day at the wheel. And a facility like this – with a cot and a communal toilet – is the only one they can pay for with the meagre travel allowance they get from truck owners. The stand, additionally, provides laundry service to the drivers and their assistants (who sleep on top of the truck) and charges only 250 rupees a night for providing all these services.

Naeem believes their artistic illiteracy is the result of a certain mindset among the elite that wants to deliberately keep these painters as artisans – as executors of someone else’s ideas – rather than letting them become artists.

A soft orange sun rises above the signboard for the stand and the drivers begin to stir. Allah Ditta Rabbi, a towering Pakhtun with hazel eyes and a bushy black moustache, stands next to his truck as he sips chai. He scrapes off mud from the sole of his shoes by grating them against the truck’s tyres and looks around, displeased. His kleender is still asleep.

The kleenders are usually young boys aiming to become drivers. Their wages are their driving lessons though they are also paid a few hundred rupees as a stipend each month. Besides learning how to drive, they also develop some understanding about the mechanics of a truck and are responsible for its upkeep and general maintenance.

Rabbi was a young student when he got married at the age of ten. He had to drop out of school and find a job. He worked as a kleender over the next ten years and then became a driver; he has been driving trucks across Pakistan for the past fifteen years. “I am paid 15,000 rupees per month,” he says when asked about his wages. For every trip (he makes around six trips each month), he gets about 2,000 rupees for out of pocket expenses on food, accommodation and any other emergency that may arise on the way.

When asked about his family, he laughingly replies that he has twenty-five children — an obvious exaggeration. Other drivers squatting near him pat his back as if in celebration of his prowess to produce children in such large number and start talking in Pashto; they tug at his shalwar and have a hearty laugh. An elderly man guffaws and gently hits Rabbi on his head. “Rascal,” he says – it is unclear if he is congratulating the younger driver on his fecundity or his attempt at lying.

Rabbi says, like most drivers, he gets to visit his home in Peshawar after four to five months and he never knows how much time he can spend with his family. He recounts how he went home late one night but received a call from the adda that there was an urgent delivery to be made to Karachi. So, there he was, readying to go on another long road trip only after spending a few hours with his family. “Who will earn if we keep sitting with our children? Our families know that this is our home,” Rabbi says, pointing to his truck.

Sabzi Mandi conducts most of its business on rotting leftovers of the previous days (and months and years). Buyers, sellers and workers make their way through stalls set up on sheets of cloth spread over smelly, sticky mud. On a foggy day in February, a man is beating a dhol in one corner of the market and some drivers are dancing to the tune next to a truck packed with onions.

A grand portrait of Musarrat Shaheen, a Pashto film actor from the 1990s, adorns the back of the truck. She is wearing a police uniform and a fluttering Pakistani flag forms the backdrop of her image that seems to be watching dancing drivers with disapproval. “Qanoon ka ehtaraam karain (respect the law)” is written next to her. In the male-only truck economy, a woman’s presence is as fictional as the police’s ability to induce respect for law.

Yet there are some rules that truckers have to follow whether they like them or not. Restriction on entry to certain spaces and at certain times is one such regulation and it is resented by most drivers and their kleenders because it makes them wait many hours on open roads without any protection from the elements.

A small man hops out from the back of a truck at the Ravi Toll Plaza – a few kilometres to the north of Lahore’s Sabzi Mandi. He holds his hands above his wiry grey hair, shielding himself from the afternoon sun. Four trailers and many trucks stand parked next to the plaza, awaiting permission to enter Lahore. Goods transporting vehicles cannot enter the city before 11 pm, the man says. A long wait is ahead of him.

He leans against the body of his vehicle, covered with natural scenery painted in bright hues: a brick house with a conical roof and a chimney emitting smoke is nestled next to two gleaming hills surrounded by a thick forest of conifer trees with a river flowing through the middle of it; lotus flowers float alongside boats and buffaloes in the river.

It cannot be the Ravi River — a meandering trickle of polluted water that passes by Lahore, with nomads and factory workers living on its sandy bed in makeshift shacks. Some displaced truckers, too, use the river bed for parking and resting.

An ornate orange truck with a number plate registered in Dera Ghazi Khan turns right off the main road that leads out of Lahore’s Sabzi Mandi to the western and southern outskirts of the city. The vehicle starts moving on a mud track that goes down steeply and comes to a halt nearly 12 feet below the road level, amid an expansive truck stand right on the river bed. No tree-studded mountains here; no lotuses floating on water. A little left to the stand, however, buffaloes bathe lazily in the shallow and sewage-strewn river water.

Ahmed Shinwari, who owns the truck stand, has a long family history of being in the business. His grandfather moved to Lahore from Peshawar and set up a stand in the 1960s. “Transport industry was flourishing in those years,” says Shinwari.

A crowd gathers as he starts speaking agitatedly. For many years, his family’s truck stand had been the envy of adda owners as it was the place most drivers preferred to stay at: it was right next to Sabzi Mandi and was well-connected to the rest of the city.

In late 2013, Punjab government officials told Shinwari his stand had to be relocated to make way for a flyover at Azadi Chowk right next to Minar-e-Pakistan. The flyover was completed within the next six months “with a sign that read no high-bodied vehicles [such as trucks] were allowed” to use it.

Displaced and without a government-approved alternative, Shinwari has been using different sites – including the river bed – to cater to the truckers who have been his regular customers for years. “When India releases water into the Ravi, our entire adda is submerged,” he says. “Injustice upsets me, poverty does not.”

Elsewhere, poverty is a much bigger problem. Consider Dera Ghazi Khan — again.

Three young boys sit behind Ustad Manzoor Chamak Patti Wala on the floor in his workshop besides low wooden tables. The eldest of them is Waleed. He is only 12 but is dexterous at drawing flowers on adhesive tape. He also cuts multiple pieces from coloured reflective tape in the shape of diamonds, hearts and raindrops and pastes them onto the flowers he has just traced. He then removes the protective file from the back of the tape and pastes the entire piece on a metal sheet that is later fixed to a truck’s body.

Waleed started working with Ustad Manzoor more than a year ago after he lost his father to an illness. He has a large family that includes his mother, grandparents and eight siblings. His day starts at 8 am and can stretch well into the evening, with a few brief breaks in between. By his employer’s account, he gets 1,500 rupees a month — about 10 per cent of the national minimum wage as provided by the law. He himself acknowledges receiving only a hundred rupees a week. “This boy is still learning,” says Ustad Manzoor, suggesting that an apprentice cannot get the salary of a trained worker. Waleed, however, appears efficient, producing decorative flowers with the consistency and speed of a grown up man.

Sajid and Majid, two brothers, sit next to Waleed. They are barely old enough to be holding a pencil but wield sharp knives to pull out stencilled patterns from the sticker tape. Their salary: Ustad Manzoor says he pays each one of them 600 rupees a month; Waleed says the younger one gets 10 rupees and the older one 15 rupees each week.

On February 4, 2016, Balochistan Goods Truck Owners Association called for a strike across Pakistan in collaboration with the All Pakistan Goods Transport Alliance. The members of these associations held a sit-in outside Sindh’s Chief Minister House in Karachi, demanding the removal of vehicle tax and reduction in toll tax. The protest got no press coverage.

Haji Gul Kakar, a representative of the truckers, is not happy with the failure of the protests. Sitting in his well-lit one-room office with a window that looks on to the Hazar Ganji truck stand in Quetta, he laments: “[The government] will ruin us just like it has ruined the agriculture industry in this country.”

With close to 300,000 privately-owned trucks registered across Pakistan (the exact figure for 2011 was 223,152, according to the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics; this number has been increasing by about five per cent a year), Kakar says each truck pays nearly 3,500 rupees as toll tax every month and 10,000 rupees as vehicle tax every year along with sales tax on the fare it charges. Such high taxes are “economic murder,” he protests.

Drivers at the stand mention a dilapidated bridge – that links Hazar Ganji with Quetta – to highlight the government’s indifference towards their business. Part of the bridge collapsed in 2013 and has not been repaired even though the provincial and the federal governments have built several road projects in Balochistan since then.

Many at the truck stand believe that keeping the bridge the same way is a deliberate ploy by the government to slow down the movement of trucks for their stringent monitoring by law enforcement agencies. These claims are impossible to verify though.

To make matters worse, the Frontier Corps (FC) in Balochistan in particular, and police, anti-narcotics force and customs authorities everywhere, are said to be extorting large sums in bribes from the truckers. Sometimes, these law enforcement agencies make truck drivers and kleenders unload their entire luggage to check whether it includes smuggled goods or drugs. Labourers then have to be called from nearby trucking stations to reload the luggage which, according to Kakar, adds to both costs and travel time.

Hazar Ganji is an expansive truck stand a few kilometres out of Quetta. Surrounded by jagged mountains that jut out towards the sky as if praying for rain and snow, the stand was shifted here nearly 10 years ago from Satellite Town within Quetta city.

The window in Kakar’s office provides an exquisite view of the trucks that stand in the foothills. It seems like an ideal place for the truck decoration industry to flourish because of its sheer size and strategic location close to Pakistan’s border with Iran and Afghanistan that attracts truckers from all over the country. Yet this is not the case.

Akram Dost Baloch, an eminent artist and head of the fine art department at the University of Balochistan, says shifting of the truck stand has had a detrimental impact on truck painting in Quetta. “There are very few truck painters in Quetta now.” The artisans, most of them Hazaras, under attack for their distinct ethnic and sectarian identity, do not feel safe to travel all the way to Hazar Ganji for work. As a result, they have either stopped working as truck painters or have found a new, and much smaller, canvas — auto rickshaws.

This is not a space for women,” is the message received from truck painters in Peshawar when I want to visit them on the Ring Road. Yet the city is the only place where I hear of a woman being a part of the truck decoration workforce. Allah Nur, working on creating a border with chamak patti around the image of a lion on the side of a truck, says the design he is using is, indeed, created and carved by his wife. She designs and traces panels of chamak patti at home that he brings to the adda for pasting on trucks.

She is perhaps the only exception to the rule in the trucking universe: no women allowed. Sometimes, sticking to this rule creates awkward ironies.

A truck painter in Multan is painting Lollywood actress Saima on the back of a truck on the request of a driver. He meticulously works on reproducing the contours of her shirt which is almost clinging to her body; her skin gleams from behind it like brown satin. He, then, suddenly looks at me and tells me to cover my head in the manner that conforms to Islamic guidelines. “God will be happy with you,” he says and returns to painting the voluptuous curves of

Saima’s body.

A meandering path** on the outskirts of Peshawar leads to the shrine of 17th century Sufi poet Rahman Baba. This white mausoleum, bombed by the Taliban militants on March 5, 2009, is often frequented by truck drivers. Next to it is a madrasa, built in 2000. Local residents narrate how the madrasa students stop visitors from going to the shrine, trying to dissuade them from paying respects to the saint. These efforts are reflective of a conflict that has existed between orthodox Islam and Sufi Islam for centuries and is now finding a new space for its manifestation: trucks.

Elias writes in his book how orthodox Muslim proselytisers and even militant groups are trying to use this space to propagate their ideologies. Very obvious religious messages – even calls to jihad – are not difficult to find on the backs of trucks moving on Pakistani highways. Truck painting could be facing some of its worst days ahead.

This was originally published in the Herald's May 2016 issue. To read more subscribe to the Herald in print.

The writer is a staffer at the Herald. She tweets at @zehra_nawab.

Photographs by journalist Quratulain Ali Khan, who has a masters degree in journalism from Columbia University. Her work has been published in Caravan, Marie Claire, Tanqeed and Roads and Kingdom. She tweets at @pakistannie.

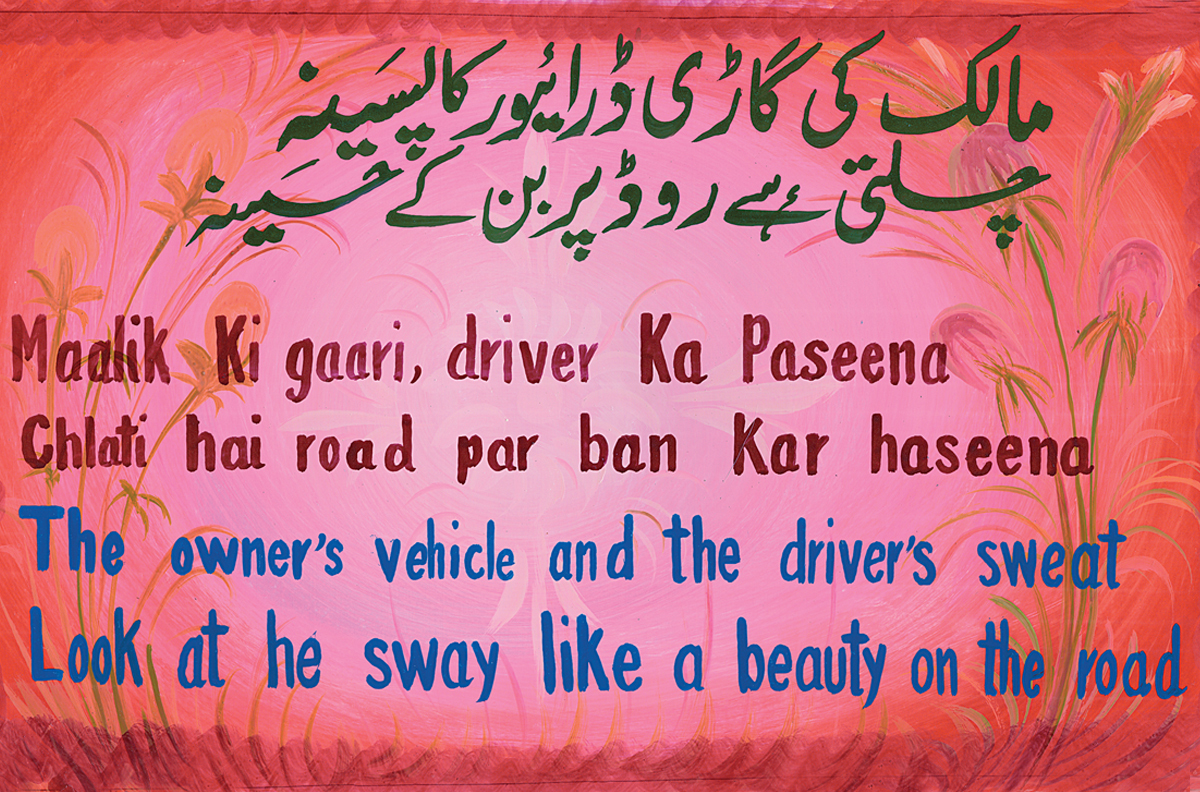

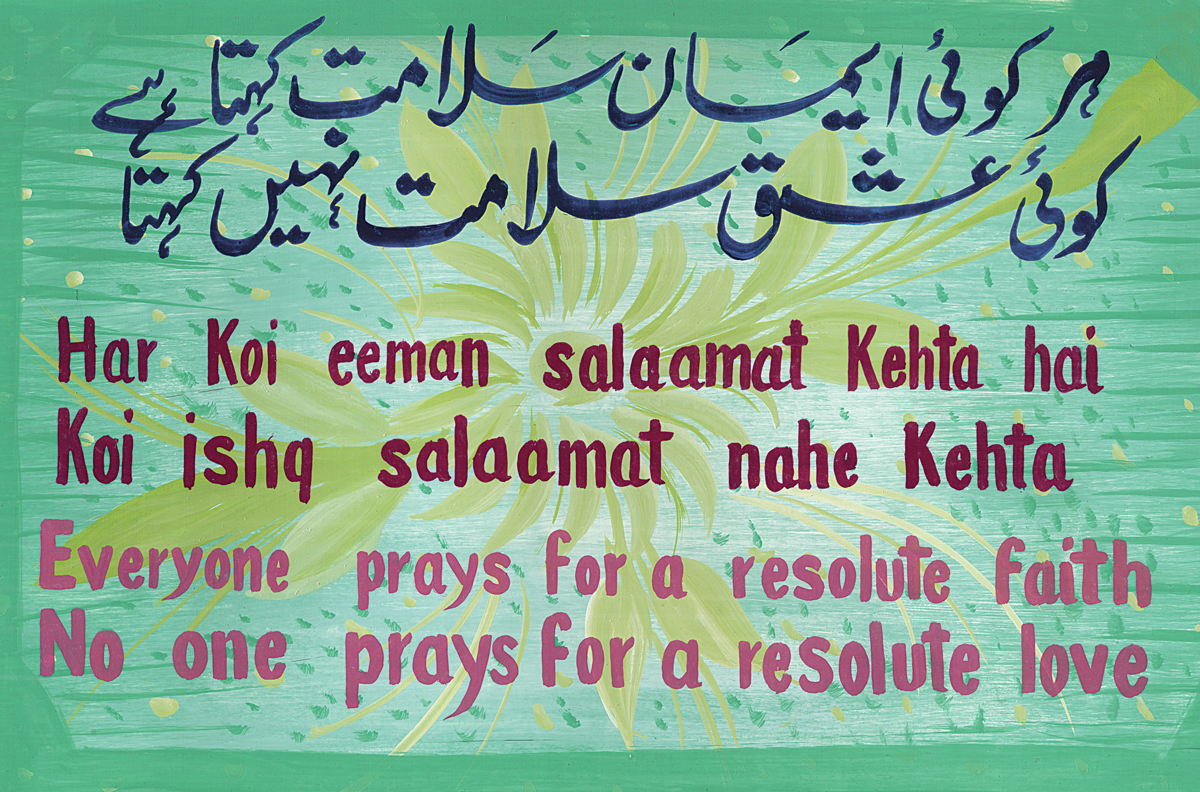

The illustrated couplets have been painted by Mohammad Islam and Saqib Muneer who paint trucks in Karachi, Pakistan.

The photographer was earlier referred to as Annie Ali Khan. The name has been changed on her request.