By Alizeh Kohari

Videos & photographs |

Fahad Naveed & Saman Ghani Khan

Design | Fahad Naveed

PART ONE

Six-and-a-half million acres of sprawling desert, nine men to each square kilometre of sand — yet on that morning, Cholistan seemed very much like a small town. From the settlements near the crumbling fort to the canal-straddled fields miles away, everyone brought up the wedding in the desert, talking about it with the casual familiarity of next-door neighbours.

"Those women there, they wear too much make-up," said Hafeeza, wrinkling her nose and lowering her voice, as if they really were next door. She lived in the desert too, but her own house, next to Derawar Fort and near a road, seemed to make her regard herself as separate from the nomads deeper inside, where the metalled road faded into the white flatness, dahar, of the desert. "And such glittery clothes…!"

Further away, on land made arable by a trickle of irrigation water and a cocktail of fertilisers and pesticides, Rasheeda's eyes lit up. That was a family wedding, she said; most of her relatives lived there, in the deep desert. Many years ago, a plot of land had been allotted to her father-in-law; in order to cultivate it, she lived here now with a few of her sons and her daughter and her daughter's daughter, a sombre-eyed girl of eight. Some weeks ago, this granddaughter had also very nearly been married off, in a tricky case of watta-satta – a form of bride exchange – averted at the very last minute.

"There was henna on her hands," Rasheeda said grimly, drawing the little girl close.

The bride at the desert wedding is only a little older — 12, they say. She sits stricken in the centre of a charpoy, bowed by jewellery and flanked by cheerful women relatives. Out in the open, the groom, older but clearly a young man still, looks equally burdened: the garland around his neck covers almost his entire frame and, for good luck, he clutches a metal stick, heavily embellished. Around him, guests cluster near cauldrons of food or lounge under shamianas — curiously, this desert wedding is being arranged by a professional caterer.

Later, a singer from a nearby town will arrive rattling on a scooter, a man in a festive yellow kameez with perfect black hair and brilliant white teeth and the self-conscious air of a minor celebrity, but for now women gather outside the hut of the bride and sing songs: old ones passed down over generations and newer ones popular on the radio, their desert dialect speckled with slang and snatches of Urdu:

It is the hyperbolic lament of a doomed lover – a sad song, technically – but the women don't sing it in that manner. They sing it triumphantly, twirling their hands, transforming the song into a celebration of difference: desert-dwellers thumbing their noses at the settled life of cities. All around them, past the caterer-provided shamianas, past the tractor trolley piled high with stacked chairs, the desert stretches endlessly: sand in the air, sand on the ground, small eddies of sand swirling into the horizon. This entire vastness belongs to them, in theory if not on paper: when this pond of water, their toba, shrinks to a puddle, they will gather their animals and move away, to wherever the presence of water leads them. It is what their forefathers have done, for hundreds of years.

And yet, as the government prepares to further colonise the desert through a new round of land allotment, slicing it into neat little squares of twelve-and-a-half acres each, more than fifty-four thousand applications have poured in from this desert of just two hundred thousand people, each filled form effectively a desire for a different life. All across the desert, from Hafeeza's household to Rasheeda's relatives to the settlements in Bijnot so deep within that the Indian army captured them in 1971, every Cholistani family expresses just one wish: for a plot of agricultural land they could call their own.

Like his namesake in the Persian epic Shahnameh, Rustom Abbasi has an association with kings. He belongs to the same clan as the nawabs of Bahawalpur, who in turn claim descent from the eighth-century Baghdad-based Abbasid dynasty. Some historians are sceptical of this lineage, even while the Abbasis brandish it like a badge of honour. What we do know is that at some point in the early 18th century, the warrior chieftains that ruled Sindh began fighting with each other and one faction, the Daudpotras, moved north, settling just below the Sutlej-Chenab-Indus riverine sequence. After clashing with the ruler of Jaisalmer to the east, they conquered his desert fortress, Derawar. This marked the start of the state of Bahawalpur.

"Oh no, but I am not that sort of an Abbasi," quickly clarifies Rustom, with a slight trace of sheepishness. Clan is one thing, but there can be no confusing kings with underlings.

It is night, late night. Rustom sits cross-legged on the ground, scratching dull roots hidden in the sand.

A song plays shrilly on his mobile phone: the voice of a woman, possibly Reshma, crackles and bursts the air. All the land lying 300 kilometres to the east and 300 kilometres to the west, he proclaims grandly, belongs to the nawab. Truth be told, this is a bit of an exaggeration: the federal government inherited most of it when the princely state acceded to Pakistan in 1947 and was absorbed into the One Unit in 1954. But significant landholdings still do belong to the former first family, and to a panoply of extended relatives, and Rustom's somewhat dull-sounding job is to keep watch over this private property in and around Derawar.

Still, he sometimes seems to have stepped straight out of the pages of a book — the unreliable narrator, perhaps, or a fanciful side character with a secondary plot of his own. He speaks in gruff bursts of sound and is often funny without realising it. He dreams of finding gold beneath the grounds of the fort and aspires to make a fortune by ensnaring black scorpions and selling their venom to pharmaceutical companies. He proudly displays the pair he has already caught, small and boggy and brown, scuttling precariously in a metal bucket. And, gesturing towards an elongated ditch-like depression in the ground next to him, he recounts a story, ordinary enough without context, but surreal in the emptiness of the desert.

"This used to be a canal," he says.

Water flowed here once, irrigating fields of wheat and cotton and cane. Sometime in the late 1980s, he says, a delegation of Cholistanis presented themselves before the nawab and made a peculiar request.

Stop this water, they begged. Our animals are dying. Upon closer inspection, the ditch does appear to be a watercourse, abandoned now, dry as bone. A waning moon shines weakly on the loosened bricks; scrub grows between the cracks. Rustom clearly tells this story to demonstrate the munificence of the nawab, to contrast his large heart with the indifference of the successive governments: he halted cultivation so that nomads in the area, exclusively herders, could continue grazing their animals. The nawabs of Bahawalpur actively cultivated this image — the emblem of the state was a pelican, a symbol of selflessness because of its tendency to feeds its offspring its own blood at the cost of its own well-being. But Rustom's story is also instructive for another reason: as an indication of how land, even one that seems as immudiv as the desert, changes over time.

Water flowed here once. Cholistan, perhaps more so than any other desert, is haunted by this thought. Nomads sing songs longing for water, songs bearing witness that water was once here. In one desert melody, a river surges into the Indus at a place called Pattan Minara, the site of an ancient Buddhist monastery, now just a spindly stone structure — this is the lost Hakra River, the sacred Saraswati extolled in the Rig Veda, Hinduism's third great river, which researchers now agree is more than just a stubborn myth. In another desert song, the rivers Beas and Sutlej tumble down from the mountains like 'two released mares' or 'two cows playing with each other' — both rivers now flow in Pakistan only in name, having been awarded to India under the Indus Waters Treaty. In another melody, a poet tries to reason with a river, imploring it to calm its raging waters and let him make his way across.

Only if you write me a poem, replies the river coyly. So that the world remembers me when I'm gone.

In order to love the desert, wrote Edward Abbey, a chronicler of the American west, you have to get over the colour green. But this particular place was green once, and settled. On the dry bed of the Hakra River lies a stretch of land called Ganweriwala, an unexcavated archaeological site spread over 80 hectares. It is believed to be at least as old as Mohenjodaro and Harappa, possibly one of the largest cities of that period, linking the two civilisations. Today, this buried complex appears as sheer wasteland; a road tears straight through the site, say locals. It makes sense then that a story about an abandoned canal at the edge of the desert assumes special meaning, an anomaly and an allegory, like a motif in a poem, mixing memory and desire.

That water is essential to life is a cliché flatter than a Cholistani dahar, but isn't it still intriguing how the desert is the only landscape defined by what it lacks? Granted, dearth of water dictates desert life: it is why Cholistanis eat what they eat, dress as they dress and live as they generally do. And yet, when you are physically in the desert, the thought of water won't immediately grip you. Instead, you will marvel at the dizzying amount of land.

No boundaries of asphalt. No structures of concrete. No pylons or power lines. Not a single right-angled surface, as Abbey would say — just wild, rolling land. The sense of openness can make you giddy. Blink: perspective will dissipate into thin air like a mirage. Unlike other landscapes, desert seems to have no physical or teleological end-point: mountains have summits, oceans have shores and rivers opposing banks, but the desert just exists, mysterious in its openness, suspect in its seeming lack of purpose. Perhaps this inscrutability is why so many people prefer other landscapes, other wonders: the lofty scale of mountains, the toot and rattle of big cities, even the staid sensibility of the plains. The desert doesn't care much for the casual visitor; it won't preen or primp or shake its tail feathers.

So what do you do if you are lost in the desert, if you can't make sense of the land? Those who travel on wheels – hunters and aid workers, wildlife officials and government sub-engineers – make symbols in the sand with their tyre tracks, squiggles and circles to mark their turns, a method that on a windswept day is as precarious as a trail of crumbs. A lost Cholistani will remove his turban and place it on a tree or a dune, a teela, higher than his own head, a recognised distress signal in the desert. If it is night, he will navigate the stars. Of course, now that one cellphone service provider offers network coverage across the area, this lost Cholistani will probably just telephone for help — a decidedly less romantic but far more efficient option.

As for me, lost in a different sense, I looked at a map. It was only marginally helpful: Cholistan appears as a pale yellow smear squashed into the south-east corner of Punjab, far away from the centres of power, unlikely to fire anyone's imagination except perhaps those drawn to voids. Beyond Derawar, there are scarcely any metalled roads, nor any other cartographical signs of civilisation. Unlike the Thar Desert, there are no proper towns — Bijnot, the largest of the Cholistani settlements, comprises a single row of fluffy-headed huts, gopas, a congregation of underground wells and a pristine-white padlocked mosque.

So, I started making my own notations on the void. I marked the site at Ganweriwala, one among 400 ancient sites in Cholistan identified by veteran archaeologist Rafique Mughal, then shakily traced the bed of old Hakra, often regarded as the de facto boundary between 'lesser' and 'deeper' Cholistan. I marked out the rows of tottering forts scattered across the desert as well as the 5,000-acre spanking new solar park, set to add a hundred megawatts to the national row. I drew the Lal Suhanra National Park on the edge of the desert, a curious synthesis of forest and desert life. It was very much an outsider's perspective, this annotated map, I realised, paying scant attention to the people who actually lived there. Which led to another thought: what do other people see when they see the desert?

I thought of the indignant media reports that emanated from Thar last year, depicting an admittedly difficult desert existence as downright hellish, a miasma of mass migration and dying babies — even as experts like Arif Hasan argued that the trouble was deeper-rooted, the inevitable result of ill-managed modernity. I thought of Khwaja Ghulam Farid, roaming the desert during the late 19th century, sensing in its starkness a metaphor for the human soul. I wander through mountain and desert like rippling dunes, set moving by the thrusts of feet as they danced, he wrote ecstatically. I thought of a more recent poem, written in a different timbre, berating visitors to Cholistan for lapsing into exotica:

I looked at the map again. What would a politician see? Unlike the Thar Desert, a large part of which is an administrative district on its own – Tharparkar – Cholistan is spread over three districts: Bahawalnagar, Bahawalpur and Rahim Yar Khan. Not a single electoral constituency, federal or provincial, comprises solely of the desert; it forms a scattered, inconsequential vote bank. No Cholistani has ever assumed an office higher than that of councillor, lament locals; in contrast, Arbab Ghulam Rahim, a native of Thar, has served as chief minister of Sindh. A military man would zoom in on the extended boundary with India; the 'soft belly' deemed so vulnerable during the India-Pakistan standoff in 2002 that it was stuffed with landmines, a last-ditch attempt to deter invasion. Some of these landmines are still undetonated, so cows and camels sometimes explode in the desert. Once, six members of a Cholistani family died en route to a wedding ceremony; a year later, the hunting party of the finance minister of the United Arab Emirates strayed from its regular route and met a similar fate — one man died and two others were injured. An Indian monkey called Bobby once strayed across the border into Cholistan; it was duly arrested by Pakistani authorities. A dead falcon fitted with a small camera was discovered in Rajasthan; Indian officials alleged it was a spying machine from Pakistan. The army carries out militaryexercises in the dead of the desert: large tracts of land are officially allocated for this purpose, and you can sometimes see armoured vehicles shrouded in twigs and tufts of leaves trundling up a dune, the white flags on their hulls fluttering merrily in the wind.

Still so much land, despite this use by the military — just lying there, unaccounted for. That is what a settlement officer would see on the map; he would approve of the land allotment taking place in parts of the desert. Cholistan is one of the few areas of Punjab that still largely exist outside the land revenue record; the rest was settled by colonial administrators during the mid-19th century, a process that was murky at best and downright traumatic at worst. In some areas, it didn't so much change the face of Punjab as freeze it in time — certain castes and classes were granted individual private property rights while others were implicitly dispossessed: agricultural tenants, labourers and non-cultivating service providers. The new landowning castes also benefitted when canal colonisation was introduced in the land between rivers, doabs. The original inhabitants, dismissed as jaanglees, were shunted to one side. The colonial settlement of land was clearly a political act, even if it was touted as a means of raising revenue: it identified and ossified social hierarchies, honoured certain claims and disregarded others.

Today, there are many claims on land in Cholistan: the government, the desert tribes whose ancestral presence predates the state, the military, the 28 legal heirs of the nawab, even the Arab sheikhs of Dubai and Abu Dhabi who descend into the desert each year to hunt the poor houbara bustard. In this noisy messy modern age, no claim is easy to entirely ignore, although there currently appears to be enough land in the desert to accommodate most of them. But ambition expands and land contracts and a tussle of some sort is inevitable; indeed, writes economist Haris Gazdar in The Fourth Round and Why They Fight On: An Essay on the History of Land and Reform in Pakistan, it lies at or near the heart of most ongoing conflicts today: the insurgency in Balochistan, urban violence in Karachi, even the trouble in the tribal areas. Who will win these tussles — and more importantly who will lose and how much?

I looked at the map of Cholistan one last time. Suddenly, the pale yellow smear seemed alive.

Old Allah Bukhsh owns a thousand camels. This technically makes him a very rich man — after all, an ordinary camel bought for slaughter can cost anywhere between 60,000 and 200,000 rupees. Even if his animals aren’t the meatiest or the sturdiest on the block, even if they fetch a middling 100,000 rupees each, that is still a great deal of money. A hundred million, to be precise.

That afternoon, Allah Bukhsh sits in his semi-pukka settlement of Nagra Khun, with his limp dhoti and crisp turban and creased forehead. A younger man sits on the charpoy next to him, a native of the area who now divides his time between toba and town. What a difference a generation has made: the young man wears strapped sandals and a lilac turban; there is a watch on his wrist, a cell phone in his hand and a pair of dusty sunglasses on his nose. I look back at Allah Bukhsh, at the stick in his hand and at the pointy khussas on his feet. I think of the word ghareeb. It doesn't really mean penniless, even if we mostly use it in that sense now — it means foreign, alien, estranged. It seems to fit the old man before me.

There are two reasons for the creased forehead. Winter is setting in and foliage is thinning out. Rain is increasingly unpredictable. There was a time when the forest department would scatter seeds from helicopters; upon rainfall, they bloomed, adding to pastureland. But the practice has been abandoned. In fact, this year there is a new trouble: the Cholistan Development Authority, the main administrative body in the desert, began cleaning and expanding 1,100 of the 1,800 officially recognised tobas in the area but inadvertently ended up upsetting the ratio of water and pasture. So even while water shimmers in the toba at Nagra Khun, foliage has withered away; Allah Bukhsh's animals wander further and further away in search of grassland and the more they travel, the weaker they become and the less milk they consequently produce. Is it time to migrate then, to abandon all that water? It is a cruel choice for a nomad to have to make.

"There is nothing left in livestock," laments the man with a thousand camels.

"So then?" I ask.

"Raqba," he says meaningfully. A plot of land. The man sitting next to him nods vigorously.

Allah Bukhsh actually already owns land. His family was allotted twelve-and-a-half acres miles away from Nagra Khun during the 1970s — although by now, divided over the years and across generations, each family member's share has dwindled to mere marlas, a few hundred square yards. He doesn't cultivate this land, though; he has leased it out to tenants. Still, he wouldn't mind a bit more. Like most Cholistanis, he is convinced that this is the path to prosperity — although he isn't quite sure what he would do with it. "Will you cultivate it yourself?" I ask.

Allah Bukhsh shrugs. Allotted land comes with no guarantees: it could be undulating, it could be insufficiently fertile and it could well be devoid of even a drop of water. Most people have to invest a fair amount of personal resources, often even selling a few animals, to make the land fit for cultivation. One man admitted that he didn't have the money to level his plot, so he approached a former union council nazim for help. The politician agreed to develop the land — but at a price. All produce from the land for the next eight years had to go to him. But this doesn't really bother Allah Bukhsh as such. At the very least, he reasons, he'll have a place to keep his animals when he migrates to the settled areas each winter. At the moment, he is always worried: when his cows and camels sometimes stray into unwelcome fields, the landowner's farmhands fire shots in the air to disperse them. Sometimes they are directly fired at.

"It happens whenever there is a Noon-League government at the centre," he insists, referring to the government of the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PMLN).

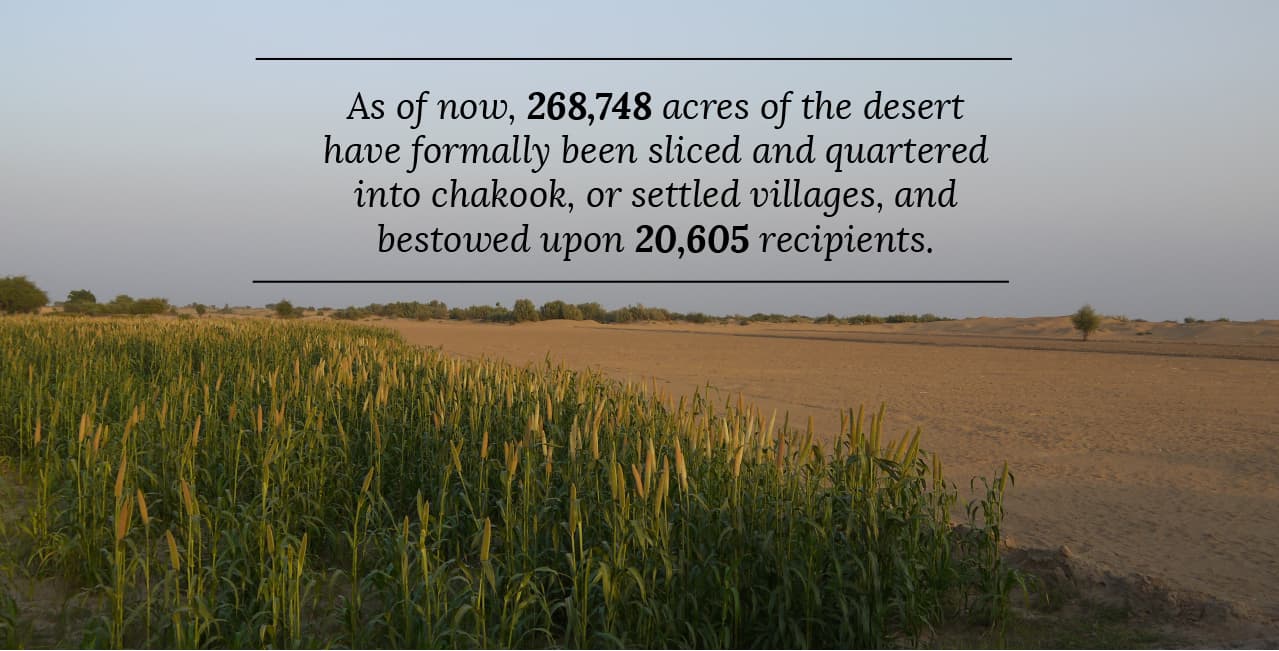

Since 1959, when the Grow More Food Scheme was launched, multiple rounds of allotment have taken place in Cholistan: as of now, 268,748 acres of the desert have formally been sliced and quartered into chakook, or settled villages, and bestowed upon 20,605 recipients. Some schemes catered only to Cholistanis; others were less specific. Land was also given as compensation to those displaced by developmental projects across the country: 481 people affected by the construction of the Pat Feeder canal in Balochistan, 357 by the military cantonment in Okara, 164 by the Muzaffargarh canal and 132 by Lal Suhanra National Park. A few of the families displaced by the construction of Tarbela Dam are also said to have been granted land here. So were the families of 133 soldiers martyred during the Kargil War.

In the ongoing scheme, between seven and eight thousand plots of twelve-and-a-half acres each will be made available — exclusively for Cholistanis, insist officials. The process is admittedly rigorous: applicants must provide receipts of paid teerni (livestock) tax as far back as the 1980s. Their names must be present on the voter lists prepared for the 2008 elections. The permanent address on their identity cards must be listed as Cholistan. The village headman, the lumberdar, must verify all these details.

Of the 54,115 applications submitted, only 20,000 to 25,000 are likely to hold up to scrutiny, say officials. Even then, corruption is rife. Identity theft is common. It isn't very difficult to prepare bogus papers claiming Cholistani nativity, especially if you happen to have a friend in the bureaucracy. Many locals also complain that the palm of the lumberdar must be sufficiently greased before he can be persuaded to authenticate credentials. Some of the headmen have collected money in sacks, locals allege, although there is no way of verifying this. Meanwhile, others who feel they are being unfairly excluded devise ingenious ways of inclusion: a local reporter related how he discovered that some childless Cholistanis were giving human names to their camels and listing them as their offspring on official documents so that they could transfer their existing landholdings to these purported children, present themselves as landless and apply for more land.

Something else is also troubling Allah Bukhsh, the other reason for his furrowed forehead: the CDA is refusing to renew his identity card. The authority ostensibly directed the National Database and Registration Authority (Nadra) to stop issuing new cards following announcement of the new land allotment scheme — officials explain it as an extra measure put in place to avoid scams. But this shouldn't preclude renewal, argues Allah Bukhsh who says he has been mistreated during multiple recent visits to the CDA head office in Bahawalpur.

"They mistreat us because we are Cholistanis," he says angrily. It is an accusation commonly levelled at the authority, given the nature of its setup; it is headed by the Chief Minister of Punjab, falls under the mandate of the Punjab Board of Revenue and to date has never had a Cholistani as part of its governing body. This constitutes modern colonialism, its staunchest critics argue. And so even as Allah Bukhsh weaves plans for his new plot of land, he remains wary. Within Cholistan and beyond, there is a lingering suspicion that the authority continues to aid and abet a practice older than its own existence and wider in scope than just the unsettled desert: that of systematically allotting land to outsiders.

11

11