By Aliyah Sahqani, Sarah Dara and Aliya Farrukh Shaikh

Photos by Mohammad Ali, White Star

Relationships

Anchal Mirza fell in love with a 22-year-old man when she was 35. She would talk to her beloved every day before she “bought a ticket and went to see him” in his village in rural Sindh. Soon, they decided to get married. The wedding took place in a marriage hall in Karachi and was attended by Anchal’s friends and members of her community.

After the wedding, her partner said he wanted to take her to his village. She wore her most decent clothes and went with him even though she was apprehensive that his family would not accept her as his spouse. When she reached the village, her worst fears came true. On the very first day, her partner took out his phone from his pocket and switched on a recording of her groans and gasps. She was aghast: the recording had been made during one of her pre-wedding rendezvous as a sex worker. “My blood went cold,” she says. Her partner went mad with rage and started torturing her. His whole family called her a prostitute.

Anchal ran away — arriving back in Karachi and resuming her life in the big city as a sex worker. Looking back at those days, however, she is rather forgiving and says she understands why he was upset. “How can anyone tolerate their spouse getting physical with someone else?”

In a photograph taken around that time, she looks attractive — even seductive: it shows her prominent nose, a heavily made-up face, high cheek bones, jet black hair falling smoothly below her shoulders and an exposed cleavage.

Anchal looks nothing like that now. Her face has become dark and wrinkled, her cheeks have sunk, her hair has visibly thinned and frizzed and her body looks haggard. Around eight months ago, she was diagnosed with hepatitis C. “I lost a lot of weight. I used to cry every night,” she says as she recalls the days and nights before the diagnosis.

Anchal moved to her hometown, Lahore, sometime after her ‘marriage’ broke down but continues to visit Karachi and other parts of Sindh to meet customers. Now that she is ill, she can no longer engage in sex work and works as a manager for some other sex workers. They all live with her in a small house where they also entertain their customers.

Anchal was born as Mirza Waseem in 1980. She was uncomfortable in her male body from the beginning and always wanted to be a woman. She was still a teenager, having passed her 10th grade, when her parents died. Since her siblings did not accept her feminine ways, she had to leave her house and become a sex worker in Lahore. “If you think like a female and dress like one, you also want to join this line of work,” she says.

Her siblings would tell her to stop being a sex worker. They would call her friends, asking them to bring her back home. She also craved their acceptance — but on her own terms. She offered them more than 110,000 rupees so that they could have her turned into a woman through surgeries and accept her as their sister. But they refused. “We would rather piss on such money [given how it is earned],” is how they dismissed her offer.

A few years later, she expanded her clientele to various towns and cities in Sindh and started living in Karachi. It was then that she became romantically involved with her future partner. Since theirs was a marriage between two men, it did not seek approval of the state and the society. Instead, a guru – an older transwoman who has the self-assumed status of being an elder of the community – supervised the wedding ceremony. The marriage deed, though legally unenforceable, had the weight of a whole group of transwomen and their guru behind it. One of its many provisions covered infidelity: the partner found guilty would pay heavy fines to the other.

In retrospect, Anchal would have liked some provision against mental and physical torture as well — and perhaps also a mention of some kind of a medical insurance.

A few months ago, a man poisoned himself in Faisalabad. He survived but the police and his family turned up outside the Karachi apartment of a transwoman, Mehek. They knocked at the door, asking her to come out. She ran away with a friend.

“I met that man at a dance event. He kept giving me money later so that I gave him all my attention. When I did not, he consumed poison,” she says in a recent interview in Karachi.

Mehek’s voice is deep like a man’s but her face is feminine. She dyed her hair blonde a few months ago and is proud of how it compliments her olive skin. She has a long nose and kohl-rimmed eyes that appear to be hiding some mystery.

She also takes time to open up and does not tell much about her early life. It is only after a few meetings that she pulls down her shirt and reveals a faded tattoo on her right breast. It reads ‘Usman’ written in Urdu.

Mehek says she fell in love with Usman when she was 13. “We met at someone’s outhouse. He was drinking and I was looking at the moon. Then I looked at him and he looked back at me. We were in love instantly.” The two were together for the next seven years but then he left her for a woman.

After Usman abandoned Mehek, she took to drugs and alcohol to heal her emotional wounds. When that did not work, she started slashing her forearms. The scars have healed but the pain remains.

What made it worse for Mehek was that Usman’s wife would show up at her house and heckle her loudly, calling her khusra — a Punjabi word for a transwoman. Mehek cursed her back, retorting, “May you never have a baby.”

Those brawls took place a year ago and Usman’s wife has been unable to get pregnant during this time. “There is this popular superstition that the curse of a transwoman does not go unrealised. I never used to believe it but I started doing so after Usman’s wife could not conceive for months,” says Mehek — neither sad nor happy over this turn of events.

Usman recently came to see Mehek and begged for forgiveness. She forgave him but does not know if the curse has ended too.

Shehzadi Rai is a big fan of Indian actress Aishwarya Rai whose last name she has also adopted. She was born a boy – and was named Shehzad – to a father who worked as a deputy manager at the Pakistan Steel Mills in Karachi and a mother who was a school principal in the same city.

Shehzadi left her home soon after she turned 18 and started staying with another transwoman. Later, she moved into a rented apartment with three other transwomen — fearful that her older brother might beat her to death. She now lives in an apartment of her own in Karachi’s Gulistan-e-Jauhar area.

Shehzadi is lean and lanky. Her hair is long and wavy, her facial features are soft, her lips thin and her almond eyes small. The only apparent sign that she is not a woman is her prominent Adam’s apple. She says she is 30 years old.

Early one evening a few weeks ago, Shehzadi has just woken up and is sitting on the floor inside her house. Like most people in her community, she sleeps during the day and stays awake at night. She stopped being a sex worker a few years ago. She also no longer performs as a dancer at private events — something most young transwomen do for a living.

She, instead, is in relationship with three men whom she calls her ‘husbands’. Together, they take care of all her expenses. Two of them come to see her daily, she says. “We sit together and smoke hashish at night.”

The third one is married. “He introduced me as a friend to his wife,” she says. The wife also became friends with Shehzadi — until she read text messages exchanged between Shehzadi and her husband and found out about their relationship.

Shehzadi has had similar relationships with other men too. One of her former ‘husbands’ gave her one million rupees after she spent time with him in Dubai some years ago. She spent the money on buying the house she now lives in.

Makeovers

It was a cold night in January 2011 when Sarah Gill renounced her identity as a boy and left her family apartment in Karachi’s posh Defence area. She moved to the house of a transwoman she had met through a social media platform. The woman helped her become a dancer and a sex worker. Sarah was only 14 at the time.

Sarah has undergone facial surgery to make her lips fuller and cheekbones higher so that she can look like her idol, Indian film actress Kareena Kapoor. She also gets Botox injections regularly and has had part of her male genitals removed. “The things God did not give me have been given to me by doctors,” is how she describes these changes.

Sarah does look a bit like Kareena Kapoor. Fair and slender, she has thick lips and delicate facial features. Her dyed dark brown hair fall smoothly on her thin shoulders. If anyone sees her in a public place, they will never think that she was born a man.

Now 23 and a fourth-year student of medicine at a private university in Karachi, she is regarded as a ‘sex symbol’ among her fans and friends. Men throw money at her when she performs at dance events and pay her an asking price to have sex with her. “As long as prostitution is helping me earn my medical degree, I don’t mind it,” she says in a matter-of-fact manner.

Sarah lives in a three-room rented apartment in a commercial neighbourhood of Defence area. Her bedroom is painted orange. It has velvet curtains and yellow lights. She shares the place with Payal, another transwoman who, according to some members of her community, has undergone many sex reassignment surgeries (SRS). They claim that her posterior, calves and chest have been reconstructed by surgeons in Thailand. But Payal denies these claims vehemently.

Shehzadi, on the other hand, dreams every night of getting SRS – so that all her male genitals are removed and replaced with female ones – but the cost is prohibitive and the fear of medical complications strong. She knows of a transwoman who underwent SRS but has been left with decomposed genitals.

When Shehzadi was 13, and was still regarded as Shehzad by her family, she recalls, her breasts started growing in size — an unusual development for a boy. Her family sought to ‘fix’ the ‘problem’ through traditional means. Her mother would put an ironed towel on her chest to stop her breasts from growing and a practitioner of indigenous medicine gave her testosterone to consume with milk every night for a year. This led to excessive hair growth on her body.

Five years ago, she took some medical measures in the opposite direction. She got silicone implants to make her breasts look bigger and had a part of her genitals removed. To avoid legal complications, the doctors who did the latter procedure wrote in her medical record that she had undergone radical prostatectomy — a surgical procedure done on those suffering from prostate cancer.

Simmi Naz is a ‘fully-operated transwoman’.

She was born 30 years ago as Asif Ali in Lahore and was initially raised as a boy alongside two sisters. But, much to the wrath of her mother, she would sneak out of her house at night, wearing her sisters’ clothes, jewellery and make-up. Her mother would beat her up, though her father would let her be. By the age of 13, she took up her female name and became a transgender person publicly.

Simmi now lives in a one-room residence in Jinnah Colony, a poor neighbourhood behind Karachi’s Jinnah Postgraduate Medical Centre. She is short, has broad and bulky shoulders, and a big belly.

Simmi has spent a lot of money on reconstructive surgeries. She got breast implants three years ago. The surgery, involving the insertion of silicone gel pads into her chest tissue – costing 100,000 rupees – was done overnight in Lahore, with no follow-up visits required. She was only instructed to keep the stitches warm for a week. A year later, she had female genitalia implanted from Dubai. The procedure cost 500,000 rupees.

Simmi’s reason for undergoing these elaborate and costly surgeries is to attract male attention and, thereby, earn money. “Men come to us when we look like real women,” she says.

The surgeries seem to have worked — at least as far as attracting attention is concerned. Her boyfriend says he cannot take his eyes off her. If she goes to a dance event, more men are attracted to her than to other transwoman. And even though she lives at her boyfriend’s house along with his family, her ex-boyfriend keeps calling her. He wanted to marry her but his family rejected her, calling her a man. That was before she had undergone the surgeries. Now his sisters themselves request her that she marry their brother.

But all is not well with Simmi. Her animated face turns solemn as she complains that the surgeries have left her weak, rendering her unable to dance as she used to. Her bones ache if she does anything strenuous and she irritatingly mentions how various procedures have led to the release of hormones that have caused excessive hair growth on her body — something she did not have to worry about when she was regarded as a man.

She gets a regular laser treatment to rid herself of facial hair and calls a waxing lady home for the removal of bodily hair.

Given a choice, most transwomen in Pakistan will opt to undergo some form of a sex reassignment procedure to complete their transition from being a male to becoming a female. Many of them want to be castrated to decrease the growth of their male hormones. Others want breast implants. Some want both. A complete sex change is termed an orchiectomy and involves the replacement of all genitalia.

The process usually starts with estrogen injections that increase the growth of female hormones and make breasts grow. Before any surgeries are performed, tests for hepatitis B, hepatitis C and HIV – the most common diseases among the transgender community in Pakistan – are conducted to prevent their spread afterwards. (Data put together by the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV and AIDS – UNAIDS – in 2018 states that 5.5 per cent of all members of the transgender community in Pakistan are HIV affected.)

Insertion of breast implants is probably the most widely conducted procedure in Pakistan. A lot of transwomen have gotten implants for as low as 80,000 rupees from unauthorised hospitals operating within residential areas in Lahore and Karachi. “No one knows what is going on inside those hospitals,” says a chest specialist at a private hospital in Karachi.

Some countries – such as Iran, Syria and Egypt – have legalised sex reassignment procedures but there is no clear prohibition or permission for them in Pakistani laws. A urologist at a private hospital in Karachi says there is nothing illegal about them — provided they are necessitated strictly by medical reasons. Some children, he says, are born with either genetic or physiological defects that make the determination of their gender difficult. These defects must be caught early and corrected by medical professionals, he adds. At just his hospital, according to the urologist, 25-30 surgeries are carried out every year on such children.

News media also frequently reports cases in which doctors prescribe and perform sex reassignment surgeries even for adults. For instance, an 18-year-old girl became a boy after undergoing a gender change surgery in December 2018 in Gilgit-Baltistan’s Diamer district; two sisters in Chichawatni town (in Central Punjab) underwent sex reassignment surgeries in 2006 and 2014; in 2013, a woman in Toba Tek Singh (also in Central Punjab) converted to a man through surgeries two years after her marriage.

But, in many other instances, doctors have refused to perform sex change surgeries without explicit permission from legal authorities. Two women – one in Islamabad and the other in Peshawar – moved high courts in 2018 for permission to undergo surgeries for the change of their gender. One of them, 22-year-old Kainat Murad, stated in her petition that she was “almost a male” but could not undergo a sex reassignment surgery because the doctors wanted her to “get the high court’s permission”. The verdict is awaited in both the cases.

Surgeries might be justifiable in all such cases – both in legal and medical terms – but removing one set of human organs and replacing them with another for non-medical reasons is certainly prohibited in Pakistan. In children, it constitutes genital mutilation, says Dr Sana Yasir, Pakistan’s first intersex educator.

The cosmetic surgeries desired by transgender people fall in the prohibited category because, as the urologist says, it is impossible to decide whether they have a medically treatable problem or they are seeking a sex reassignment surgery for some other reason.

Many transwomen in Pakistan still want to – and do – undergo such surgeries. Those who can afford to, get these procedures done by qualified doctors both within the country and abroad. Those who do not have enough money resort to cheaper – and also dangerous – methods. For as low as 15,000 rupees, a guru in a remote rural area will cut the undesired genitalia with crude tools and unsafe mechanisms.

These guru-led surgeries seem like violent orgies. The transwoman seeking the surgery is made to consume alcohol before the procedure so that she does not feel pain. Then her genitals are cut with a sharp knife and the wound is doused with hot mustard oil and some ointment. The whole process is carried out in a secluded place to keep it secret.

Anything can go wrong during these rudimentary surgeries. Anecdotal evidence suggests that transwomen undergoing such procedures usually lose consciousness for an inordinately long time but, to maintain secrecy, they are not taken to any healthcare facilities. In other cases, they receive scars that refuse to heal.

Sometimes a surgery conducted by a guru results in excessive bleeding and also leads to death. If and when a transwoman dies as a result of a surgery gone wrong, she is quietly buried then and there.

Community

On an early winter night in Karachi last year, an all-male gathering inside an empty plot next to a police station in Lyari neighbourhood is waiting for the arrival of some transgender dancers. No woman is allowed inside the venue. It is strictly a men’s-only event. The dancers arrive dressed in revealing female clothes. Over the next few hours, they dance to film and folk music while men congregate around them, cheering them up and also throwing money at them.

Dance events – or ‘functions’, as they are called by those involved in them – are a major source of income for transwomen. They usually take place around midnight. Their locations vary — some are arranged in secluded areas outside big cities, others take place inside ‘safe’ houses or empty lots blocked from public view. These events often become possible with the connivance of the concerned police station.

The function organisers contact performers either through men who have already seen them perform or through their gurus. The modes of communication between the two sides range from phone calls and text messages to various social media platforms. Many performers have their accounts on social networking sites such as Facebook, Instagram, Tik Tok and Vigo Video, where they post seductive photos and videos of themselves and receive private messages from prospective clients.

These functions get rowdy and violent quite often. Sometimes men ask dancers for a dance off; on other occasions, they order them how to dance and how not to. Occasionally, they clash over the choice of dancers —different groups supporting different sets of dancers. Fights erupt, sometimes resulting in injuries.

Men also vie to attain the attention of dancers — usually by giving them more money than others. Occasionally, violent force is also used to achieve the same objective.

A good-looking and young transwoman dancer, known among insiders as a mashooq, sits at the top of an internal hierarchy of Pakistan’s transgender community. She also engages in sex work but selectively. Below a mashooq is the professional sex worker, or a peshaver, and then come the beggars, or toli.

Looking as much like a woman as they possibly can is important for pashavers and mashooqs since their earning depends on their looks. The most feminine-looking among them can earn as much as 100,000 rupees per event as dancers. Their sex work also fetches a high price. “We have to do a lot of things to get attention,” Sarah says. This includes attempts to have the best hair, get the most attractive make-up and find the most fitting dresses, etc. “If we wear one dress at a function, we will not wear it again because people notice.”

There are some regional variations in how a mashooq is treated by men around her. In Punjab, sex work is considered dirty. A mashooq doubling as a peshaver is considered impure and loses her appeal. If a mashooq becomes a sex partner of one of the men at a particular function, others present there will not invite her to perform at any other function. The word then spreads about her and she becomes a persona non grata.

Men in Punjab also do a ‘full-body survey’, scrutinising a mashooq from head to toe, says Simmi. Even the feet of a mashooq need to look smooth and fair, she says as she gently rubs a foundation cream on her feet. Some men touch a mashooq’s face to see how much make-up has been applied. Look pretty, they demand, but also look natural.

Not that sex work does not take place in Punjab. It does but it is a discreet and underground affair. This is not the case in Sindh in general and Karachi in particular.

Transwomen also sometimes prefer sex work over dance performances. “I will get 3,000 rupees if I perform at a function in Karachi but I will get around 10,000 rupees if I do sex work twice a night,” says Simmi.

Some mashooqs are so popular that their fans take them abroad both for performances and company. Sarah and her roommate, for instance, were asked to perform in Bangkok recently. There they also found themselves to be in high demand as sex workers. “Pakistani, Indian and Filipina transwomen are most in demand there,” says Sarah, giggling.

While part of a transwoman’s appeal lies in looking like a woman, most men are attracted to her for what she can offer and a woman cannot: she can play both, a catamite and a sodomite.

All this works as long as the bodies of transwomen are young and taut. Once they start wearing out, opportunities to earn money from dancing and sex work also shrink. Most of them then either become gurus or they join a toli to seek vadhai, or alms, by singing and dancing.

Simmi is on the cusp of having to make these choices soon. She plans on working as a dancer and a sex worker for another couple of years and then she will “find an old guru and start seeking vadhai”.

Chhanno is more than 50 years old and lives in a small room in Azam Basti, a slum off Karachi’s Korangi Road. Her lodging was bought years ago by her parents and is part of a bigger structure consisting of many rooms of similar size and shape. These are occupied by her relatives. “I have lived here all my life and I will die here,” she says.

Chhanno, a guru of the transgender community in her area, is obese and dark and spends most of her time inside her residence where she sleeps on the floor and plays with her little nieces and nephews. She has a man’s voice and her hands are rough. In pictures from her younger years, she looks fairer and thinner.

Chhanno attends every celebration in her neighbourhood. If a child is born or if someone is getting married, she will go to their house along with her chelas – or disciples – who will sing and dance in anticipation of vadhai. “The people who perform at functions are different from those who go from house to house to sing, dance and beg,” she says. The latter group is usually older, darker and not so good-looking.

On a Sunday evening late last year, Chhanno is getting ready to attend a pre-wedding event not far from her house. She applies heavy make-up on her face and adorns herself with heavy jewellery. She gets into a pink laacha, a long skirt of sorts that has golden embroidery on it. All the while, she is waiting impatiently for her two chelas – Anjali (who, like many other transwomen, is a trained make-up artist and has worked at a salon in Islamabad) and Aarzoo – to show up. The bride’s family has already reminded her twice that she is running late.

When her chelas finally arrive, all three have a quick, small meal. Then they set out of the room in the setting sun — but only after praying quietly for a few minutes.

Chhanno prays regularly. Being a Christian, she goes to a local church every Tuesday and is warmly welcomed by the nuns there. She also celebrates Christmas with fervour, spending the night before it in worship at the church. On December 25, after early morning service ends at 4:00 am, children in her family decorate her palms with henna. She then visits her neighbours, wishing them a merry Christmas and celebrating with them. She follows the same celebratory routine on Eid days.

Her own guru was a Muslim who told her that every religion was as important as the other. There is no religious discrimination within the transgender community, says Chhanno. “It does not matter what religious beliefs its members have.”

As Anjali and Aarzoo gyrate and sing in their male voices, Chhanno provides the occasional beat with her loud clapping. The audience throws money at them while they perform. The family of the bride also gives them some cash in vadhai – essentially a handout given to have better luck – as they end the performance profusely wishing the bride and her parents well.

Throughout the performance, Anjali and Aarzoo vie for the attention of their guru. They crave her approval and want to be the centre of her attention. This sort of competition often results in odd occurrences: a chela may like to dress herself again if she finds that another chela is looking better than her and is, thus, getting more attention from the guru.

A guru, indeed, is revered by her chelas more than anyone else. “If [my guru] tells me to bring eggs for her, I will get those for her before doing anything else,” says Shehzadi. Though she is relatively young, she has her own chelas who revere her similarly.

Most transwomen in Pakistan try to get into this guru-chela system in order to have access to a stable clientele – both as sex workers and as dancers – and also to protect themselves against exploitation, violence, as well as police raids and arrests. Young transwomen, who have to leave their own families, find alternative families – and also shelters – by joining the guru-run networks. Usually, a guru and her chelas live together in the same house, creating a family structure of their own.

An elaborate ceremony is held when a chela enters a guru’s network. Members of the transgender community are invited from far and wide. Food is served generously. Many song and dance routines are also performed.

The central event of the ceremony is the adoption of the chela by the guru. How it is done varies slightly in different transgender communities. Sindhi gurus pierce the nose of their chelas as a token of acceptance whereas Urdu-speaking gurus put a red dupatta on their chelas’ heads to fomalise their association. A new name is also chosen for the chela –— sometimes by the guru but often by the chela herself.

A guru is as much a mentor, a teacher and a protector as she is a manager. It is the guru whom the organisers of a dance event have to talk to in order to sort out the logistical and financial details — as well as the number of performers required. A guru also guides her novice chelas on how to dress up and how to attract male attention during a performance.

In return for all this, a guru gets a share of the earnings by her chelas. “You have to give to the guru [because she] gives you her tutelage and her name,” says Shehzadi.

The system also works as a survival insurance for ageing – as well as aged – transwomen.

After their looks fade and their bodies grow old, transwomen start performing at vadhai events (that are informal and short compared to events organised by men who seek entertainment). Older transwomen are preferred for vadhai because of a popular perception that their prayers are more likely to be accepted.

This stage in a transwoman’s life also signals the start of her career as a guru — a stage in which she will not be doing anything herself but will be living off her chelas who willingly contribute to her expenses.

A guru also plays an important role in hitching a transwoman with a man — the former providing sex and company and the latter financial security. The guru becomes both the guarantor and the enforcer of the terms and conditions of their relationship.

Some of the strictures of such relationships have been eased with the changing financial needs of young transwomen. Those requiring more money for their upkeep often get into relationships with more than one man and men, too, find it expedient to share expenses with others like themselves.

Like most of their internal affairs in Pakistan, transgender people in the country also have their own particular language that outsiders seldom understand. A male partner is called a girya; a transwoman is known as a moorat — a curious mix of mard (man) and aurat (woman); and a chamka is a man willing to spend money just for the sake of company. The chamkas sometimes also escort transwomen at dance performances.

The transgender language has a sentence structure loosely based on Urdu and a unique vocabulary of at least a thousand words, according to a 2018 paper, Hidden Truth about Ethnic Lifestyle of Indian Hijras, written by Sibsankar Mal and Grace Bahalen Mundu, both students at an Indian university. It is used as a survival mechanism by the community, the authors note. It helps them communicate among themselves in times of emergencies and distress, or when they do not want to share their secrets with anyone else but their own ilk.

Transgender people have, in all likelihood, existed in the Indian subcontinent forever — and possibly with all their internal divides. They are variously known as khusras (in Punjabi), hijras (in Urdu and Hindi), chhakas and khadras (in other local languages). The most socially conscious among them want to be known as khawaja saras — a term originally used for eunuchs working for Muslim rulers in the Indian subcontinent and Central Asia, mainly for communication within the gender-segregated royal palaces.

Others, the educated and politically aware ones, prefer such modern terms as transgender. Many among them do not use any masculine or feminine pronouns for themselves — instead of being addressed as ‘he’ or ‘she’, they want to be addressed as ‘they’.

Biologically, a transgender person may lie anywhere on a spectrum that includes males with partial physiology of females and vice versa. In between, there lies a whole range of transgenders who deviate from the two dominant genders – male and female – in varying biological degrees. The term transgender can broadly cover everyone on this spectrum — from a gender-neutral person to an intersex person. Medical practitioners, however, insist that not all intersex people are transgenders — only those are who at some stage in their lives make a transition from one gender to the other.

There can be more than 30 types of biological conditions in which an individual’s sense of personal identity and his or her assigned gender may not match. In Pakistan, the most common conditions are congenital adrenal hyperplasia – that causes excessive production of testosterone in females, making them develop manly features – and androgen insensitivity syndrome — that makes a genetically male person resistant to male hormones, giving them some or all of the traits of a woman. Many of the latter end up being transwomen.

Occasionally, biology plays its own tricks and gives the same person both male and female organs — making him or her an intersex person. The urologist from Karachi cites the case of a bearded Muslim cleric who needed to have a surgery for the removal of hernia. “When we opened him up in the operation theatre, it turned out that he had a uterus and ovaries,” he says.

According to Dr Sana Yasir, Pakistan’s first medical educator on gender issues, 1.7 per cent children are born as intersex globally. Given that Pakistan’s population is more than 210 million according to the latest census, their total number in the country should be as high as 3.57 million.

Almost all of them seem to be registered as either male or female as their actual number does not show in census records which puts the number of all types of transgender people in Pakistan only at 10,000. A vast majority of intersex people either do not know about their intersexuality or they – or their families – hide it.

Even though the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act, 2017, passed by Parliament in May 2018 under the directives of the Supreme Court of Pakistan, provides that transgender people have the right to register themselves as a third gender, most are yet to exercise this right.

Apart from biological variations, there are also many psychological scenarios in which people may not like the genders assigned to them at birth. Someone born a woman may want to be a man. Such individuals are called transmen. Or a man by birth may seek to be seen as a woman. Such people are called transwomen. They could be at various psychological stages of transition between the two genders. Transvestites – people who dress and behave like members of the opposite sex – are perhaps the most obvious manifestation of these psychological phenomena.

The society at large, though, does not recognise these biological complications and psychological compulsions. It portrays members of the transgender community as being sexually deviant, socially shameful and religiously undesirable.

Activism

Mani’s first job was as a physical education teacher at a girls’ school. He was only 18 years old at the time. The job did not pay him well so he started working for a shipping company. This was before he made his transition from a woman to a man.

Mani always had many masculine traits growing up. He wore jeans and a T-shirt at home. People in his neighbourhood called him a ‘dada’ (goon) affectionately. Yet, he took time to figure out his gender. “Because we lack access to medical technologies, we do not know a lot about ourselves,” he says as he explains reasons for the delay.

Mani was around 22 years of age when he realised that he wanted to be a man. When he turned 27, he finally told his parents about his wish.

“Our families are very weird,” he says. “When, while still being a woman, I came back from work, my father would say here comes my sher (lion). Even my mother would say that my mind worked just like that of a boy’s.” When, however, he finally decided to call himself a man, his parents could not accept it. “They said Allah did not make you a man. All of a sudden the lion became a lioness.”

After coming out, Mani left his hometown (which he wants to keep unidentified) and moved to Lahore along with his girlfriend. He was able to have his gender changed to male on his Computerised National Identity Card (CNIC) a couple of years ago and runs a foreign-funded non-governmental organisation (NGO), HOPE, to work for transgender rights.

On a day early in January, he is sitting behind a well-polished wooden desk in his office that doubles as his residence near Lahore’s Cavalry Ground area. A portrait of a woman holding a candle hangs above him as he keeps playing catch with a small ball on his desk. He is dressed in an oversized grey jacket and loose pants, making him look bigger than he actually is. His eyes are dark and piercing and a thin stubble covers his pale face.

Transmen like him have different issues from the ones faced by transwomen, he says in an interview. “We are raised in female bodies so we have to face whatever a female faces in our society.”

For one, transmen do not want to leave their families — as most transwomen do. “Our biggest problem is that we are too attached to our families to leave them,” says Mani. “Our families also do not abandon us.”

Transmen are not welcome in the transwomen community — because they neither want to dance nor indulge in sex work. They also find it difficult to fit into the society at large after coming out because of having little experience of life outside home.

They similarly face many bureaucratic hurdles before they can register themselves as transmen. If a woman goes to the National Database and Registration Authority (NADRA) and wants to be identified as a man, the officials will not immediately accept her request, Mani says. He will have to provide many medical records to prove his gender.

This could well be because of the social impacts of such a gender change. “For instance, if a woman claims to be a man, her inheritance rights change,” Mani says.

Only legal and administrative reforms will be insufficient to deal with problems arising out of such a situation. “A lot of changes need to take place in the society in order for these things to become acceptable.”

[“Y]ou will be surprised to know that a million transgender women [in Pakistan] are living … double lives,” said Jannat Ali, at a TED Talk event held in Lahore in 2017. “Some who come out are shunned by the society and kicked out by their parents,” she added and argued that coming out is a turning point for a transperson “because coming out, living life as naturally as possible, is very important for your physical health, for your sexual health and for your mental health”.

Jannat hails from Lahore. She is a business administration graduate from a private university but her interest always lay in dance. She finally got the chance to learn it from Nahid Siddiqui, one of Pakistan’s best known classical dancers.

Jannat is also the founder of Saathi Foundation, a Lahore-based non-governmental organisation that works on issues related to the transgender community. One of its main objectives is to provide vocational training to transwomen so that they do not have to resort to selling their bodies and begging.

Sitting in a lavender room in her NGO’s office near Lahore’s Chauburji area, she says she has attended pride marches in Copenhagen and Amsterdam and has always been keen to hold a trans pride march in Pakistan as well.

Her hair comes undone from a loosely tied ponytail as she describes how dozens of transpersons carried blue and pink flags, as well as colourful banners and balloons, and marched from the Lahore Press Club at Shimla Pahari to the Alhamra Arts Council on The Mall on December 29, 2018. The participants were dressed in wedding clothes and were decked out in heavy jewellery. Some of them rode in flower-covered horse carriages while others danced all the way.

At the end of the march, they held a press conference and then presented a number of performances. These included theatre plays, skits and music by Lucky and Naghma, transwomen who have performed in a Coke Studio song.

“Members of the khwaja sara community are always celebrating someone else’s birth or wedding but we never get to celebrate ourselves. This trans pride was an opportunity to do just that,” Jannat says.

It, though, did not attract as much publicity as she had hoped. The press coverage was scant and the money collected for it – through donations – fell short of the expenditure, says Jannat. She still has to pay 34,000 rupees to the arts council in outstanding rent for using its premises.

The march nevertheless marked an important milestone in transgender activism in Pakistan. An earlier milestone was a petition moved by a lawyer, Dr Mohammad Aslam Khaki, in 2009, asking the Supreme Court of Pakistan to direct the government to officially recognise transgender people as being different from men and women. The petition was prompted by public outrage over mistreatment and sexual abuse experienced by transwomen returning from a wedding at the hands of some policemen in Taxila. The petitioner also sought the court’s directions for ensuring the economic and social welfare of the community so that they did not have to resort to sex work, dancing and begging.

The petition was heard by a three-judge bench, led by the then chief justice of Pakistan Iftikhar Muhammad Chaudhry. In June 2009, the court ordered the four provincial governments to carry out surveys to ascertain the size of their transgender populations, identify facilities available to them and suggest ways and means to punish parents who give away their transgender children to gurus. The judges also directed NADRA to register transgender individuals as members of a third sex.

Following the court’s directives, Pakistan became one of the few countries in the world to legally recognise the third sex. By 2012, transgender Pakistanis got the right to have their gender mentioned in their CNICs.

In 2017, Nadra made another important change in its rules for the registration of transgender people: they no longer need to present the CNICs of their parents; they can also get registered by presenting the CNICs of their gurus. This has helped many who have either left their families or have been abandoned by their parents.

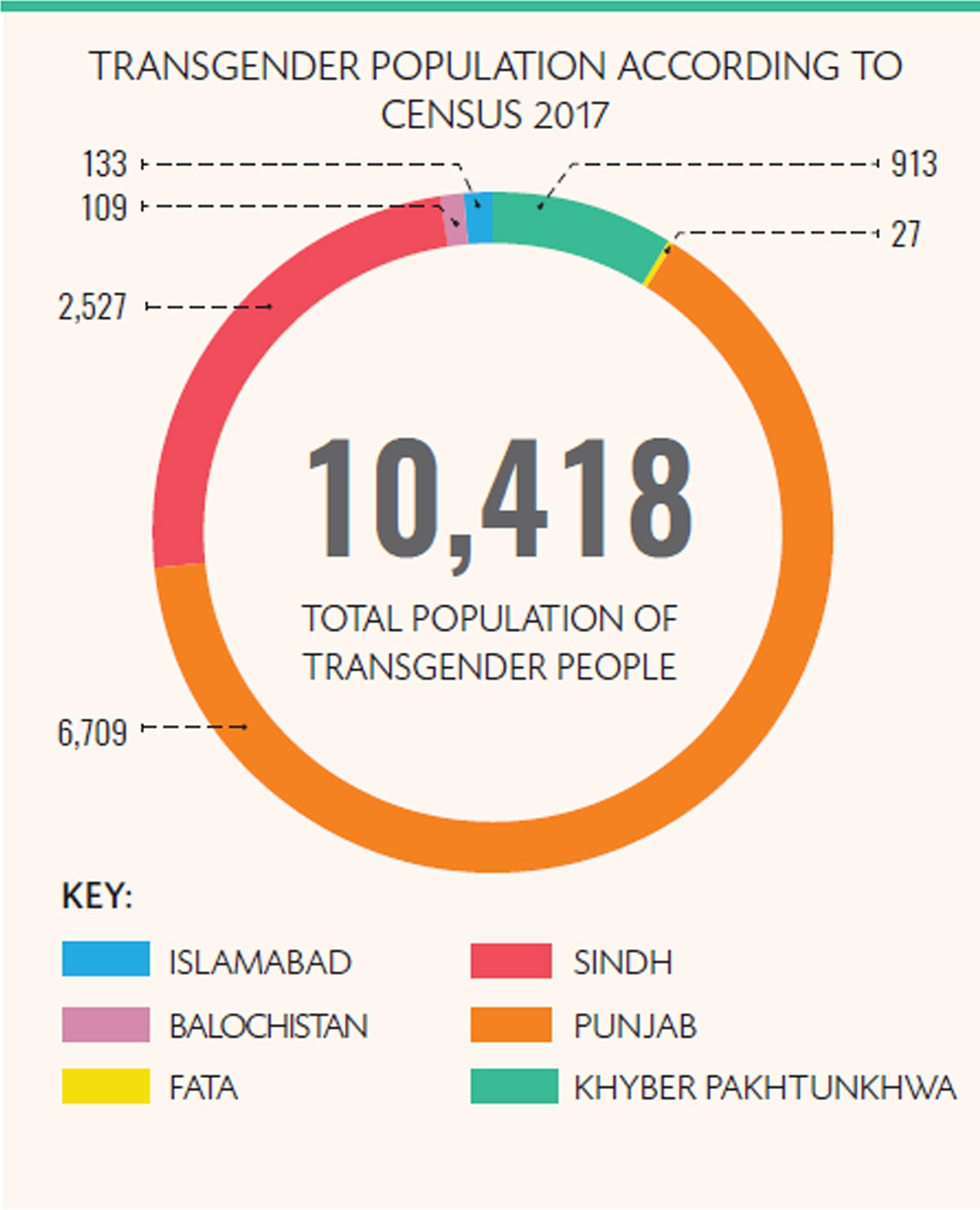

Also, as a result of the Supreme Court orders to count the transgender population, the government included them for the first time in the national census held in the first half of 2017. The census revealed that the total population of transgender people in Pakistan stood at 10,418 — constituting about 0.0005 per cent of all the people living in the country.

The number is deemed incredibly low by many transgender activists. Some of them cite a 2018 survey by UNAIDS that puts the population of the transgender community in Pakistan at 52,646. Even this figure is disputed by many. News reports suggest that the number of transgender Pakistanis can be anywhere between 50,000 and 500,000. “Karachi alone is home to more than 15,000 transgender individuals,” claims Bindiya Rana, a transgender activist and the chairperson of an NGO, Gender Interactive Alliance.

If nothing else, the controversy over their population suggests that the conversation about transgender people and their rights is no longer static and limited to a few activists. The biggest proof of this came about when Parliament – after prolonged consultations with many transgender rights activists – passed the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act last year. The act grants the transgender community many sought-after rights including the right to be identified as they perceive themselves to be, the right to obtain a driver’s license and passport, the right to inheritance, the right to vote and contest in elections, the right to assemble and the right to access public goods, public services and public spaces.

The act provides that there should be no discrimination towards transgender people in education, employment, healthcare provision and transportation. It also includes provisions for the safety and security of transgender people against all kinds of harassment and abuse, the setting up of shelters, vocational training institutions, medical facilities, counseling and psychological care services, and also separate jail wards for them. Importantly, it stipulates that anyone forcing a transgender person to beg could attract up to six months in prison or a fine of up to 50,000 rupees — or both.

But, as is the case with almost every law in Pakistan, the implementation of the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act leaves a lot to be desired. Socially and economically, says Bindiya, the community is still where it was before. “Little has been done to support it.”

Aradhiya Rai is perhaps taller than most women in Pakistan. She has an expressive round face made prominent by a pointed chin, parted in the middle. On a recent winter day, she is wearing a royal blue kameez, looking a bit tight on her broad shoulders, coupled with black tights and a black dupatta.

Last year, when she was 19, Aradhiya got a job at a fast food outlet in Karachi. She was initially hired as a cashier but was later moved to the kitchen because customers would get offended by her presence at the cash counter. She was repeatedly asked by her employer to cut her hair even though she kept them tightly hidden under a cap. Since she was unwilling to cut her hair for a job that paid her only 14,000 rupees a month, she was made to leave on the pretext that she took medical leave without proper documentation.

Mehlab Jameel, a graduate of the Lahore University of Management Sciences, who does research work for various NGOs on transgender issues, says such job-related discrimination towards transwomen is widespread. They have to hide their identities especially in order to get low-paying menial jobs, Mehlab says, and have to dress and behave like men to retain those jobs. Otherwise, Mehlab adds, they fear they will never be accepted at the workplace.

On the higher rungs of the social ladder, says Mehlab, transgender people get more and better job opportunities — such as working as make-up artists in salons, beauty parlours and even television studios. But those on the lowest rung always face the harshest discrimination, making it difficult for them to continue with their jobs and many of them soon return to the traditional ways of earning their livelihood, Mehlab argues.

Aradhiya narrates how discrimination is not limited to workplaces. During a recent trip to a fast food joint with her brother, she was pulled out of the women’s toilet by a male staffer. Letting transwomen use women’s toilet is not our policy, he informed her.

Transportation is another problem. Even though some restaurants and food outlets in Karachi have a policy to hire transgender people, Aradhiya is unable to find a convenient mode to commute to work and get back home safely in Gulistan-e-Jauhar area on a daily basis. Rickshaws and taxis are expensive and public transportation is embarrassing if not entirely dangerous, she says. “If I go into the women’s compartment, they get uncomfortable but I myself feel uncomfortable if I have to travel in the men’s compartment,” she says.

A lot of discrimination and abuse are either not seen as such or blamed on the victim. Aradhiya claims being treated as a curious object while she was studying in secondary school. Her teachers would invite her to their rooms to introduce her to other staff members as an odd person.

She also recalls how a senior in school raped her when she was 12 years old. When she reached out for support, those around her blamed her for it. They criticised her for the way she carried herself. She suffered depression over the next five years but told no one in her family about the rape.

It was only a few years later that she confided in her brother and started meeting others like her, eventually becoming a transgender activist three years ago. Although she is known in her neighbourhood for her activism, she says she still faces threats. People make prying glances into her home and send her messages telling her that they know where she lives and where she moves.

A few weeks ago, Aradhiya organised a well-attended music event. To others it might have seemed like a huge success. For her, it provided yet another proof that the society at large does not accept her the way she is. “Men in the crowd were looking at me in a perverse manner,” she says.

Aradhiya works with a microfinance organisation at a school in Karachi and is critical of the way NGOs treat transpersons. They get in touch with members of the community only as a publicity stunt, she alleges. They do interviews and take photographs but do not provide jobs or even maintain regular contact with them, she says.

Though Aradhiya is part of the guru-chela system, she steers clear of sex work. Her guru keeps asking her to start sex work in order to support her family but she says she does not want to. “My guru says to me raddi ki bhi qeemat hoti hai (even waste paper can fetch a price).” Then she asks her: “What is the price you are fetching?”

The writers are staffers at the Herald.

This article was originally published in the Herald's February 2019 issue under the headline 'Caught in the middle'. To read more subscribe to the Herald in print.