On January 9, 2018, Zainab Ansari, a six-year-old girl, was found raped and murdered in Kasur. For months, her piercing grey eyes haunted every parent who feared the same could happen to their own children. Quick justice was served in the case and the culprit was hanged within nine months of his arrest.

A Christian woman, Aasia Bibi, also received justice towards the end of last year when she was acquitted in a long-running trial over blasphemy charges. Her acquittal was followed by a violent, though mercifully brief, countrywide shutdown by champions of the blasphemy law. Aasia Bibi was consequently barred from leaving the country and is still living in state custody — as are many of those who are opposing her exoneration.

The case of Naqeebullah Mehsud, a 27-year-old aspiring model, originally from South Waziristan tribal agency, still lingers. He was killed in Karachi on January 13 last year in an alleged police encounter. His family accused Rao Anwar, a senior superintendent of police in Karachi, as having orchestrated the killing. The incident became a rallying cry for the Mehsud tribesmen who gathered, initially in Karachi and then in Islamabad, for a prolonged sit-in to demand justice for Naqeebullah. Their agitation later transformed into the Pashtun Tahafuz Movement (PTM).

A former prime minister, his daughter and his son-in-law were also clutched by the long arms of law and justice last year for owning assets beyond their means. Many assets of a former finance minister and his family were taken over by the state for his failure to stand trial over allegations of helping his boss, the former prime minister (and also co-father-in-law), abuse his financial powers. A former president and his sister, too, are facing investigation and trial over corruption, money laundering and unlawful business practices. A former chief minister has been, similarly, detained over allegations of corruption and misuse of authority while his sons, as well as a son-in-law, have also been accused of abuse of power for personal gains. A federal minister and his brother have also been arrested and are being investigated for their alleged involvement in a real estate scam.

In between these landmark cases, and perhaps overshadowed by them, an elected Parliament completed its term and an election was held to bring in a new Parliament and a new government.

Now, look back at all this again and you will find a common thread. Each of these developments has Chief Justice of Pakistan Mian Saqib Nisar written on them –– often in large print but sometimes rather finely.

He was everywhere: from guaranteeing security to Rao Anwar before he surrendered to law-enforcement agencies to taking a suo motu notice of Zainab’s killing; from acquitting Aasia Bibi to taking note of corruption in high places; and from lording over the election commission on the conduct of the July polls to ordering a countrywide anti-encroachment drive that has rendered many homeless and jobless. He has also chastised a chief minister for arbitrarily transferring police officers and hauled journalists, owners of media houses, politicians and other public figures to courts on contempt of court charges.

Justice Nisar frequently raided hospitals, not just to check the quality of the medical care they provide but also to see how some under-trial politicians were being kept there. He was enraged to find them living in luxury –– and in one famous case, possessing bottles containing suspect substances. He inspected courts — and in one widely covered incident, reprimanded a judge for using his mobile phone during court hours. He also hauled mineral water companies to court, telling them to pay for the water they were extracting from the ground.

His single most significant initiative, however, has been his untiring championing of the construction of at least two large dams in the country. He has appeared on television, addressed public seminars and travelled as far as England to collect funds for them.

All this should make it easy to nominate him as the Herald’s Person of the Year 2018.

If anyone believes that someone else should have attained that status, they must consider the fact that Justice Nisar has touched thousands of lives – certainly not always in a positive way – with his remarks, rulings and verdicts. Politicians fear to tread where Justice Nisar walks; government functionaries cower when he calls them to his court; lawyers think twice before arguing in front of him and everyone else expects either to attain prompt justice or a summary dismissal from him. Driven by his motto that the judiciary will not let “anyone suffer from injustice”, he never holds back his words or his judgments.

People look towards him to have their grievances addressed. In one instance recorded by television cameras, a woman spread out her dupatta in front of his car outside the Supreme Court’s Lahore registry, telling him that her son had been killed in a police encounter, asking him to intervene in the matter. Justice Nisar told the woman and her male relative to be present in his court the very next morning.

Justice Nisar has also made headlines with his manner of speech. “Don’t speak until I speak,” he once cut short an official of the National Hospital and Medical Centre, in Lahore, who was trying to explain something. In another instance, he scolded a principal for coming in late to school. His comparison of the length of a speech with the length of a woman’s skirt was dwarfed only by his courtroom dialogue with a highly respected octogenarian journalist and human rights campaigner, Husain Naqi.

How history will judge Justice Nisar – as a chief adjudicator who did much for public good or as a do-gooder who did not brook any judicial restraint – is not something that can be decided here and now. He has done things that many among us see as positive. He has also done things that some of us see as not so positive –– prompting the Women Action Forum to file a reference against him in front of the Supreme Judicial Council that he himself heads as chairman.

What everyone will probably find easier to agree on is that no other individual in the country has had an impact on so many facets of national life in the last calendar year as he has.

Justice Nisar is popular but this is not the only reason why he is the Herald’s Person of the Year. His contribution to national life, whether positive or negative, is also not the only criterion for his selection.

The process of finding the Person of the Year starts every year with the selection of 10 nominees from a long list of a few dozen. When the process begins every September, we, at the Herald, experience and exhibit the same confusion that everyone has: is Person of the Year a popularity contest; is it a measure of a nominee’s goodness; is it a way to give voice to the voiceless and highlight people and causes that remain missing from the national discourse? What is it that makes one eligible to be among the top 10 nominees –– and, thus, be a candidate for Person of the Year?

Here is a short answer to these questions: the single most important parametre here is how much a candidate has been in the news in a calendar year (though, of course, the impact they’ve had is also an important consideration).

However, public attention and impact do not always coincide.

Look, for instance, at the Election Commission of Pakistan that conducted a countrywide general election in July 2018. No single event from the previous year has been as momentous as the polling process itself since it has determined who will rule Pakistan until the next election. (The only other incident that came closest in historical significance is the imprisonment of former prime minister Nawaz Sharif –– which, arguably, is also largely linked to the electoral calculus). The election commission has remained under the public scanner for months – before, during and immediately after the election – for the manner in which it has conducted an election that is still perceived by a number of political parties as rigged, besides being also seen as a major contributing factor in sharpening political divisions across Pakistan.

The outcome of the election is also important because it has determined both the pace and the direction of an ongoing anti-corruption drive which, by the way, could have been a strong reason to include the National Accountability Bureau (NAB) among this year’s nominees. Throughout 2018, the bureau has been on an arrest-and-investigate spree that could be enormously significant in determining the future political layout of the country. Going by the same token of significance, the armed forces have the strongest impact on almost all aspects of national life almost every year — the previous one being no exception.

But these institutions cannot be put in a list that seeks to focus on individuals rather than on collective entities. (When a single army commander, Raheel Sharif, dominated everyone else within the military and beyond, we did nominate him –– as was the case with Ashfaq Parvez Kayani a few years ago).

It is precisely for this reason that missing persons, victims of terrorism, members of minority communities and women (as a whole) have never made it to our list of nominees even when every one of them can be found in the news every single day. Quite like the armed forces, the place of, and the space for these communities and groups in Pakistan have remained more or less constant in the recent years and decades.

If there was a strong case for including a whole section of the society in the Person of the Year nominees for 2018, it was for the children of Pakistan. Thousands of them were abducted, abused and murdered last year. Many more died of various avoidable causes. Others suffered for lack of education. We hope that the inclusion of Zainab Ansari in the list will help us highlight not just her own tragedy – and that of her parents – but also the plight of Pakistani children as a whole.

But what about groups or communities that enter or exit the national milieu depending on social, political and economic changes?

News media, for instance, has itself been in the news in 2018. Hundreds of journalists have been sacked. Many newspapers and at least one television channel have shut down. Censorship is rampant and self-censorship is endemic. On the flip side of it, social media has expanded its digital footprint in the public sphere with a rapid increase in the number of Internet users. Online propaganda wars, trolling and various experiments in disseminating news and views through social media, all made a splash last year — as did the use of social media campaigns for the July elections.

In the age of such massive social media presence, some may argue, it is unfair to focus solely on headlines from mainstream media to choose the nominees. There are, after all, many issues and people who seldom get coverage in newspapers and news channels, but are widely discussed, even celebrated, or denigrated, on social media. Manzoor Pashteen and his PTM, to cite just one example, have had a strong social media presence in spite of their virtual absence from the mainstream news media.

That Pashteen is on our list of 2018 nominees is an acknowledgment of just that: it is impossible for us to ignore social media if we want to keep our Person of the Year project credible.

Another problem that the Herald cannot do anything about is the availability of a limited space to write about the nominees. With the magazine being limited to a certain number of pages, there cannot be more than 10 nominees each year even though some people would easily make it to the nominations –– if the list could be expanded. Here are only a few of the most probable nominees for 2018 who could not make it to the final list:

Asma Jahangir died earlier last year and in her death we lost one of our most ardent champions of human rights. Her work has been so fundamentally important to the Pakistan of today that she continues to get international awards even months after her death.

Novelist Kamila Shamsie, too, has been winning awards internationally (for her book, Home Fire, which came out in 2017). And Mohammed Hanif has also made yet another forceful entry into the national literary scene with his latest novel Red Birds (though the jury is still out on the book and the manner of its reception will only become clearer once we have our annual run of literary festivals in spring).

Former Punjab chief minister Shehbaz Sharif and former president Asif Ali Zardari have both become members of the National Assembly after more than two decades. The two have also been on the wrong side of the law through most of last year. The former is in prison already, while the latter is seemingly making strides towards it.

Another political nominee who really came into her own in 2018 is Nawaz Sharif’s daughter Maryam. She addressed large public meetings across Pakistan in the run-up to the election and then, quietly, went to jail along with her father. It was only last year that she staked a serious claim to the political legacy of her father –– only to be disqualified to contest an election.

This time round, the total number of nominees is not even 10.

One of them had to be dropped midway through the three-way process that we use every year to find our Person of the Year: opinion of a panel of 10 eminent Pakistanis; a ground survey from a carefully chosen sample of around 1,600 Pakistanis (representing all the various localities, regions, provinces, ethnic communities and genders); and an online survey conducted on the Herald’s website.

While two of these processes went as smoothly as ever, the online survey became controversial immediately after it was opened for voting early last month. While we received some usual criticism for putting together people from different walks of life in the same list of nominees, as well as for mixing ‘good’ people with ‘bad’ ones, an online campaign began to discredit the entire Person of the Year exercise. A hashtag #IndianDawnHerald began trending on social media, accusing the Herald of being an enemy agent. The criticism was particularly vicious over the inclusion of Khalai Makhlooq, or aliens – a term used as a euphemism for the powers that be – in our nominees.

We withdrew the online survey. We also dropped Khalai Makhlooq as a nominee.

We, instead, devised a focus group comprising people working at the Herald as well some others who work closely with the magazine. Given the gender, age and education of the members of this group, it was an attempt at approximation to the Herald’s online readership, except that all members of the group came from Karachi. During the voting process, the group was deeply divided among Justice Saqib Nisar, Manzoor Pashteen, Meesha Shafi and Zainab Ansari (validating a confirmation bias among the well-off and educated urbanites against politicians).

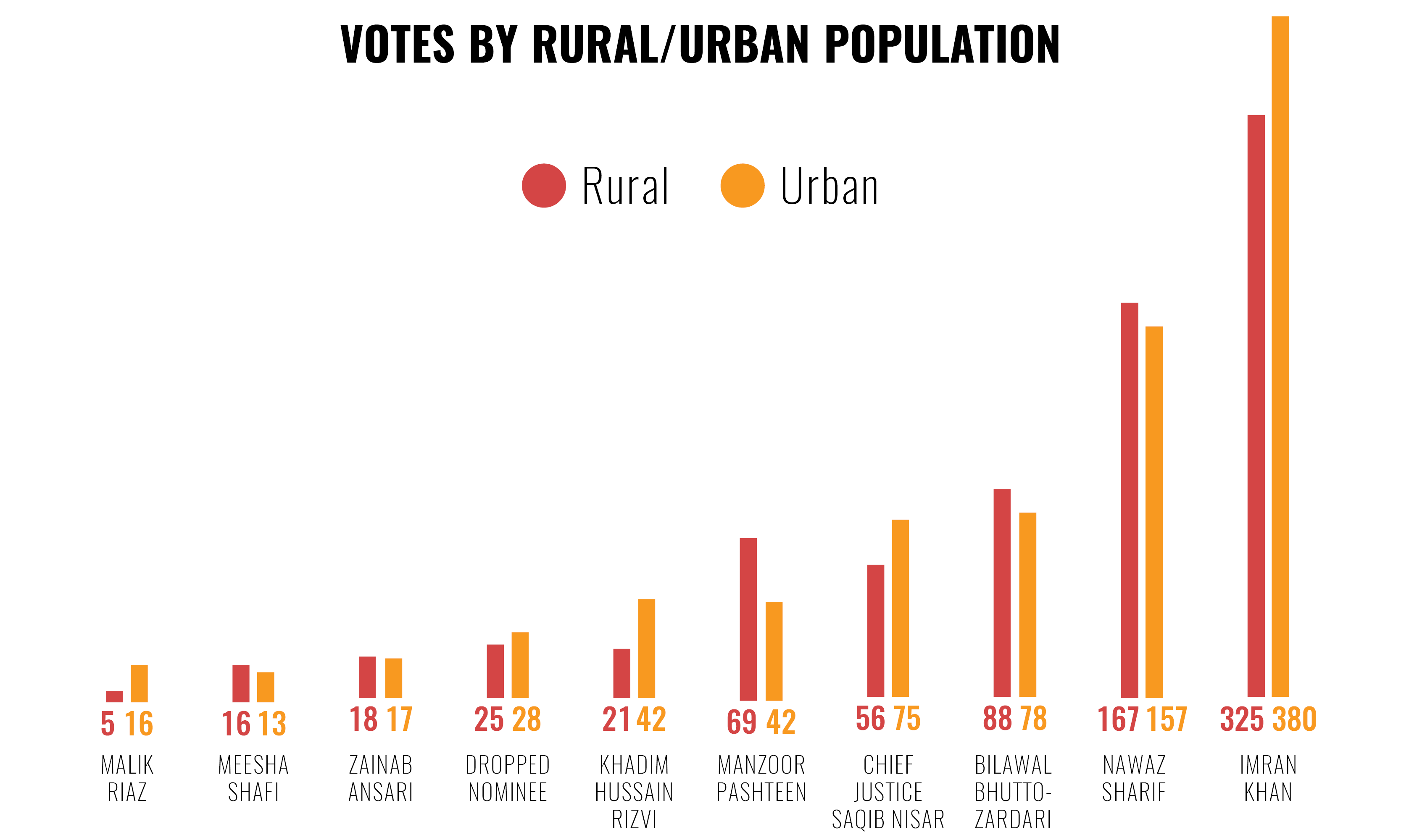

The final count of the three-way polling showed Justice Nisar ahead of others, even though he received fewer votes (three), in the panel of eminent Pakistanis, than Pashteen (four). On the other hand, Imran Khan polled around 600 votes more than those garnered by Justice Nisar in the sample-based field survey. Even Nawaz Sharif and Bilawal Bhutto-Zardari received more votes in the field survey than Justice Nisar. Confirmation bias among people at large (in favour of politicians) was clearly as strong as the one against them in the panel of eminent Pakistanis and the focus group.

We came to understand that there is no such thing as ‘Aik (one) Pakistan’, a term Imran Khan used extensively in his 2018 election campaign. There are as many Pakistans as there are Pakistanis who never seem to agree on anything. That, though, is what democracy is all about: agreeing to disagree.

Vive la democracy.

Field survey coordination by Fatima Shaheen Niazi, Hussain Patel, Sameen Hayat, Aliya Farrukh Shaikh and Manal Khan.

The writer is a staffer at the Herald.

This was originally published in the Herald's January 2019 issue. To read more subscribe to the Herald in print.