1

On a hot October afternoon, Saajan Bheel is taking a nap under a tree amid rust-coloured sand dunes. He has miles to go before he reaches a place where he can find work.

Saajan, who seems to be in his forties, has already travelled around 60 kilometres on foot but has to walk another 70 kilometres or so to arrive in Pithoro, an agricultural town in canal-irrigated Umerkot district. He is worn down by the grueling journey — a seemingly endless walk under a sun that shines brightly like a metal disc just brought out of a high temperature furnace.

A soiled white turban frames his thin dark face, glowing with a film of sweat mixed with sand. His clothes need washing and his face has grown a stubble.

A minor comfort he has is that he is not alone. His 10-year-old son Chaman, his 65-year-old uncle Mangal Bheel and his two young cousins are also with him. As are their four camels (that are carrying the children as well as the family’s luggage), 12 cows and 13 goats.

They left their village, Rohiraro, three days ago, finding it difficult to cope with the rigours of life in their drought-stricken desert dwelling. They often went hungry during the journey, receiving occasional meals thanks to the generosity of people living along the way.

Saajan’s wife, his daughters and other female members of his extended family have already gone to Pithoro — in a rented van. The only person left behind in his home is his 70-year-old father Peero Bheel. A veteran of several drought-driven migrations in his earlier years, he is no longer able to travel long distances.

Life back in Rohiraro has gone quiet. Many houses have no one inside. Others have far fewer people – mostly small children, women and the elderly – than they did before drought forced local residents to migrate in large numbers. There is hardly any animal in sight. The migrants have taken them along to greener and less dry places.

Peero, a gaunt older version of his son, has a grey brooding moustache and is wearing a coloured turban which is a little too big for his head. He rushes out hurriedly when a local boy tells him that someone has come to see him after having met his son. “What happened to him? I hope he is fine,” he says with unmistakable parental anxiety in his voice.

He breathes easy only after he is told that his son and his companions are fine and well on their way to their destination. The next thing that he says is that he is already missing his son and grandchildren though he also seems to be aware of the karmic nature of life.

When he was younger, Peero would do the same: take his family along with him outside the desert whenever there was a drought, leaving the elderly behind. “Now my children have grown up and they take their families with them, leaving me behind.”

He is also worried if his son will find work immediately after reaching Pithoro and recalls how landowners in canal-irrigated areas were much more accommodating in the past. Finding work was easy and wages were reasonable, he says. Landowners are much less cooperative now, he says, and wages are as low as 200 rupees per day. “This is insufficient considering how prices of everything have risen.”

Yet, Peero observes, even these meagre earnings are better than starving in the dry desert.

His concern about his son’s prospects in Pithoro turns out to be a self-fulfilling prophesy. When Saajan reaches there on October 16, he finds out that he will have to wait for at least four weeks to be employed. The season for picking cotton is already over and sugarcane harvesting is still some time away.

A local landowner has allowed him and his family to stay on his farmland – in shacks made from dried tree branches – and their cattle can graze on private and public pastures nearby. They still have to fetch drinking water from half a kilometer away and their provisions have all run out.

And they have no money to buy food — only a promise from the landowner that he will lend them 10,000 rupees soon. “That money will help me and my family survive until we get work,” says Saajan.

Rohiraro, a part of Chachro taluka in Tharparkar district, was a bustling village before migration started in late September this year. Purkho Patel, a local elder, says 200 houses out of the village’s total of 700 are completely empty. The rest have only one third of their residents.

Those left behind in Rohiraro – and hundreds of other drought-stricken villages in the district – are forced to eat their goats to stay alive, at the rate of two a month. Others are making do by selling livestock. One villager says he has sold many of his animals over the last three months — a camel at 60,000 rupees; 13 goats for 3,000-4,000 rupees each.

These emergency measures lead to more problems than solutions. The former reduces the number of animals villagers can sell. The latter fetches them much less money than the sale of animals would in normal circumstances. Their cows and goats have lost weight and do not attract a buyer’s fancy and their own desperation is too acute to let them demand an asking rate.

Local traders, too, are finding it difficult to get by. Maan Singh, a shopkeeper in Kuvara village, has to close down his shop because there are no buyers around — 80 per cent or so of his village’s 2,000 residents having migrated. “I am also planning to leave along with my family and animals,” he says. “There is no fodder left in the village for any animal — big or small.”

Kuvara has two schools with a combined enrolment of 322. Classes take place regularly though without 119 students who have migrated along with their parents. Many of those still in the village may do the same soon.

When the migrants come back late next spring, the academic year will have already moved ahead. Students who have gone away may have to enrol in a previous class.

A shopkeeper in the nearby village of Bheemra cannot migrate precisely to avoid this situation even though his daily sales have dropped from 1,000 rupees to almost zero. His children go to school and he does not want their education interrupted.

Kuvara and Bheemra are located within Nagarparker taluka and are only a couple of kilometres from the Pakistan-India border in the Rann of Kutch region. This southeastern part of Tharparkar district is probably the worst hit region by drought. Many of those who are still living in these villages are selling their goats for a price as low as 1,000 rupees each to survive, says Maan Singh.

They do not even have enough money to leave.

Not that the decision to leave is an easy one to make. Maan Singh, who is in his thirties, has seen many dry spells and participated in several migrations over the last 20 years or so. He understands the pain of leaving one’s home. “People cry when they leave. Not just women but men too.”

And those forced to stay behind are left to pine for those who have migrated.

A 90-year-old resident of Bheemra started missing his grandchildren badly, soon after four of his six sons and their families left for Digri town in Mirpurkhas district early this September. One month later, he asked his sons who were staying with him to take him to his grandchildren — a good 240 kilometres away. He insisted so much that he had to be taken there, one of his sons says.

The old man will not be able to live for long in Digri where his family is housed under open skies on a local landowner’s farmland.

These stories are not unique.

Their variants can be found in hundreds of villages across Tharparkar, especially in Nagarparkar taluka where, according to a local member of the Sindh Assembly, Qasim Siraj Soomro, “more than 60 per cent people have migrated to other districts over the last couple of months”. Only a few residents are left in many villages; he came across hundreds of people when he was campaigning for his election there back in July 2018.

Dr Jhaman Jan, additional director of Sindh’s provincial livestock department, offers similar statistics for animals. “Usually 50 per cent of big cattle and 15 per cent goats and sheep are taken to canal-irrigated areas during a drought, but this year the migration rate of animals is much higher,” he says. “There is not enough fodder left here for them.”

On the whole, many development activists in the district say, 45 per cent of Tharparkar’s rural population has migrated.

Spread over the Thar desert, the district should receive 200-300 milimetres of rain in three spells between May and August to maintain its status as one of the greenest expanses of sand anywhere in the world. It has not received this amount of rain in many years. Often, the rain is either scattered or scant – or both – but usually is still sufficient to grow fodder and food crops as well as to recharge underground aquifers, says Ali Akbar Rahimoo, executive director of Aware, a non-governmental organisation working in the district.

This year, some parts of Tharparkar got no rain at all. In other parts, the amount of rain was much less than normal and many villages did not receive all the three spells of rain they usually do. The district, in fact, has never received sufficient rain after 2009, says Tikam Das, a deputy director at Sindh’s agriculture department. “The dry spell this summer, however, has been the most acute.”

Rohiraro received only two rain showers last year but it was still sufficient to produce some crops — though with a much reduced yield. Local farmers harvested only 40 kilogrammes of millet (locally known as baajra) from each acre of land in 2017 whereas its average per acre yield is 200 kilogrammes in years with better rains.

This year, the village received just one rainfall. This was insufficient for crop seeds to even germinate. Purkho Patel, a village elder, says that each local farmer lost thousands of rupees buying seeds and having his land tilled with tractor. “Each local family is now under debt running in tens of thousands of rupees.”

Farmers in many other places knew better than wasting money on seeds and tilling. Sowing of rabi (fall) crops, thus, declined by a massive 80 per cent this year in Tharparkar.

Shortage of water and failure of fodder crops have also had a devastating impact on livestock in the district. The animals have lost weight and their milk yield has declined drastically. If they were not taken to canal-irrigated areas soon after the onset of drought, cows, goats and sheep would have become vulnerable to disease and death. A large (but unspecified) number of cattle have still died this year of hunger and various related ailments.

Ameer Ali Sand left his home on February 14, 2015. On a day when many in urban Pakistan were celebrating Valentine’s Day, an annual commemoration of love, he was heading to a nearby well to end his life. As he came out on the street, he heard the voice of his three-year-old daughter, Hajra. She was running after him, asking him to take her with him — as he would usually do.

Ameer Ali stopped and turned towards his daughter. He pondered for a moment. His wife had already died in 2014. He was perhaps thinking what would happen to Hajra if he was no longer there to look after her. He then picked her up and started walking towards the well again. When he reached there, he immediately jumped into the well, taking his daughter with him on one last journey.

“By the time we pulled them out, they had already died,” says Ameer Ali’s brother, Nawaz Ali Sand, in their village Mataro Sand just outside Islamkot town in Tharparkar district.

Ameer Ali was 45 at the time of his death. He left behind four other children, all older than Hajra.

What caused him to commit suicide was the dire state of his personal finances. He had sold all his cattle to get medical treatment for his wife who had contracted skeletal tuberculosis, says Nawaz Ali. After her death, he failed to make a living and his financial position continued to get worse, making it difficult for him to feed his children.

It was also the time when rains had started drying up in Tharparkar.

In 2014 and 2015, according to government officials working in the district, average per acre yield of major crops declined by 50 per cent. Farming was becoming financially unviable, drastically reducing opportunities for people like Ameer Ali to work as farm labourers in their own villages.

Ameer Ali could also not leave his village to work elsewhere because no one else could take care of his children. Jobless and with nothing to sell, he would borrow money from friends and relatives to make ends meet. Often, due to his financial woes, he would be tense, says Mangrio, a relative who also lent 2,000 rupees to Ameer Ali.

Though his suicide – and those of many other residents of Tharparkar in recent years – was not caused by drought, there is an obvious correlation between an increase in the number of suicides and the intensity of dry spells in the district. Data collected by Aware shows that the number of suicides in Tharparkar rose from 45 in 2014 to 65 in 2016 and 71 in 2017. This year the number has gone up even further. Between January 1 and October 11, 2018, according to the numbers collected by Tharparkar police, 79 people have committed suicide. On an average, these statistics suggest, eight people took their own lives in each of these months.

A major cause for these suicides has been a deterioration in people’s financial situation, says an Aware representative. Declining crop yields and shrinking livestock due to consecutive years of inadequate rainfall have greatly squeezed economic opportunities in the district, he says.

One person who does not see any link – either causal or correlative – between suicide and poverty – or, for that matter, between suicide and drought – is Irfan Qureshi who heads the district police in Tharparkar. According to him, it is the remoteness of the district, its extreme physical environment, loneliness and depression among its residents that makes people commit suicides. “Young married women often kill themselves because their husbands work faraway and they cannot get any support when they have a quarrel with their in-laws,” he says.

Yet, drought has been an aggravating agent, if not the main cause, in many suicides that otherwise may have resulted from some marital problems — as is evident in the case of Jethi Kohli.

She married a resident of Kuvara in 2015 at the age of 22 but, due to a persistent dry spell in the village, her husband could not earn enough locally so he went to some other place to have a better go at it. He was often absent from home.

Jethi, who had given birth to a daughter in 2016, was eight months pregnant in July 2017 when she fell ill. For two nights, she waited for her husband to get back to the village and take her to a hospital. When he did not show up, she hanged herself in her own house.

Maahru and his 75-year-old mother have just had their first meal of the day — a lump of boiled rice each. They have been frugal because they wanted to save some rice for their next meal.

Their shack of a home is a picture of penury. Two charpoys, a pitcher, a small tin canister – which they use both as a table and a container to store wheat flour or rice – a pitcher, a mug, two empty plastic bottles, a plate and some firewood is all they have.

Maahru is around 50 years of age and spins discarded threads and other materials into ropes. He makes less than 2,000 rupee a month by selling these ropes. “I cannot leave my ailing mother to work at some other place,” he says.

All the 400 or so households in their village, Guraro – about 45 kilometres from Chachro town – are extremely poor. Drought has only exacerbated their already desperate poverty. For two consecutive years, they have hardly grown anything eatable or sellable in their parched tracts of farmland. Goats and sheep are the only assets they have and no buyer is willing to part with their money for these skeletal creatures.

Pervasive malnutrition has made almost everyone in the village look ill. Teenagers, with their shrivelled faces and stunted limbs, appear older than they are. Small children appear younger than they are for the same reasons. If some of the local children have lost their lives recently it is mostly because their bodies were too frail to withstand any disease.

Child mortality in Tharparkar has been under the news media’s scanner for a few years now and is often portrayed as a result of poor healthcare facilities in the district. Statistics suggest the reason for deaths among children lies elsewhere.

There has been a steady increase in the number of children who died in the district over the last four years: 398 deaths were recorded in 2015 among local children under the age of five; the number climbed to 479 in 2016 (but went down slightly to 450 in 2017). This year so far, according to data compiled by Sindh’s health department, as many as 500 children have died.

A major factor that has changed for the worse over this period of time is the amount of rainfall that Tharparkar receives each year.

Local healthcare officials also claim that child mortality rates in Tharparkar are no different from – or even less than – those in nearby districts. Data compiled by Sindh’s health department shows that there were 9,733 new births in Tharparkar in 2017, a year when 157 newborns died in the district. The neighbouring district of Umerkot had 11,793 new births in the same year but had a much higher number, 487, for mortality among newborns, says Dr Ghulam Rasool Kumbhar who works as the district health officer in Tharparkar. In Tando Allahyar, another district next to Tharparkar, the situation was even worse: 426 newborns died here in 2017 out of a total of 8,197 new births, he says.

In 2018, too, 230 newborns have died in Umerkot and 180 in Tando Allahyar in the first six months of the year — as compared to 98 in Tharparkar.

News media’s focus on child mortality distracts both public opinion and policymakers from attending to some long-standing social and economic problems in Tharparkar, local healthcare practitioners say. Malnutrition among local children, exacerbated by drought, is a major reason for the high number of deaths among them, as is malnutrition among expecting mothers, they say.

Dr Aurangzeb Sand, a medical practitioner in Nagarparkar, says 400 children, out of a total of 1,864 admitted to a government hospital in the town in 2018, suffered from various degrees of malnutrition. Widespread poverty, early marriages and multiple pregnancies in quick succession also leave women vulnerable to diseases which transfer to their children, local doctors argue.

Frequent droughts, according to them, only make a bad situation worse.

Residents of Rohiraro complain of severe problems in accessing drinkable water. Underground water in the village is brackish and, with drought intervening, it has gone down too much to be drawn out easily. The nearest source of potable water is a good seven kilometres away. “It takes four to five hours daily for each family to just fetch water to drink,” one of them says.

Sindh’s provincial government has set up as many as 600 Reverse Osmosis (RO) water filtration plants across Tharparkar to address the problem of drinking water in the district. Rohiraro has been awaiting its own RO plant since 2014 when a government team drilled a pipe deep into the earth right next to the village to extract water overground. A filtration system and water pumping machinery also arrived soon but have been lying around the drilled site since then, packed in large boxes.

Early this October, some officials of Sindh’s revenue department arrive in Rohiraro and unpack the machinery — only to repack it later. They are not here to install it but to do a survey to find out if the RO plant is being set up at a location that everyone in the village approves of. “We are carrying out a similar survey in the entire district to know people’s reservations about RO plant sites,” one of the officials says.

There are widespread complaints that many sites are not to the liking of people the plants are supposed to facilitate, says Suresh Kumar, a Tharparkar-based engineer. Some other plants are meant to cater to more than one village, he says, but there are always quarrels over who will have priority access to them.

In Rohiraro’s case, the location survey appears to be four years too late. It also looks meaningless given that the location of the plant is all but determined already with the drilled pipe.

Unsuitable locations – as well as disputes over them – are not the only problems afflicting the performance of RO plants in Tharparkar. More than 150 of them are not functioning at all. At some of them, the staff appointed to keep them running has not been paid for months. At others, mechanical faults have rendered filtration and pumping machinery non-functional.

Engineer Kumar believes malfunctions have resulted from the handling of plants by untrained villagers who have been hired from local communities but have received no training to perform their duties properly. “The operators do not know anything about the desirable level of total dissolved solids in water and how that level is maintained,” he says. “They also do not change RO membranes within 12-18 months as is scientifically required.” The plants with older membranes, thus, provide water which may not be fully fit for drinking, he adds.

To address some of these problems, Sindh Chief Minister Murad Ali Shah convened a meeting on October 9 this year. Private contractors, who are responsible for the upkeep of RO plans, informed him during the meeting that their employees had not been paid since June. Shah ordered an immediate release of 336.7 million rupees to make the payment.

“Now that the payment issue has been resolved, the task of repairing and operating faulty plants will be handed over to the public health engineering department in the next couple of months,” says Muhammad Asif Jameel, deputy commissioner of Tharparkar, in early October. Another 234 new plants will also be installed soon, he says.

Increasing the number of RO plants and ensuring the smooth operations of existing ones is the only way people can have access to drinking water in a district where groundwater level in some places is as low as 300 feet and where 80 per cent of subsoil water is not fit for human consumption. “People in most parts of Tharparkar are forced to consume brackish water,” says Qasim Siraj Soomro. “They also cook their meals with brackish water which badly affects their health,” he says.

To overcome the drinking water shortage, he says, the government has also laid four pipelines in the last nine years or so to link Nara Canal – originating from Sukkur Barrage on the Indus River – with various parts of Tharparkar. “These cater to the needs of 25 per cent of the district’s population,” claims Qasim Siraj Soomro.

Most people in Tharparkar do not buy this number.

Piped water is available only in large towns, a local social worker says. There too, he says, it is available only for a few hours each month.

A resident of Bheemra village travelled 18 kilometres to reach a wheat distribution centre in Nagarparkar on a sizzling September day. Someone had told him that the government was giving 50 kilogrammes of free wheat to every family in the district (as a drought mitigation measure). Once at the centre, he was informed by government officials there that he did not qualify to receive the grain. They told him his name did not appear in a list being used at the centre prepared by the National Database and Registration Authority (NADRA) from its own records.

Deputy Commissioner Jameel concedes there were omissions in the initial list which had the records of 208,846 families in it. It was updated later, he says, when the district administration took up public complaints with NADRA. The revised list includes 276,152 families, he says, and will resolve 99 per cent of the complaints.

Many people still have complaints. In some villages, every household has decided not to get the free grain. Villagers say the new procedure is too cumbersome to be helpful.

“If I go to the distribution centre in Nagarparkar, I will have to spend a minimum of 300 rupees on transport,” says a resident of Guraro village. “Why would I spend this money to get a bag of wheat worth 1,500 rupees?”

Perhaps mindful of such criticism, the district administration is changing tack again and decentralising the remaining distribution of wheat — to be completed by November 7. Jameel says the government will select a central location that is easily accessible to a set of nearby villages and wheat will be made available there for distribution from government buildings such as schools..

The provincial government has been distributing free wheat among the residents of Tharparkar every year since 2014. One wonders why a workable system has not been devised yet.

Part of the answer may be found in frequent changes in the distribution process. Initially, district authorities dispatched a lump sum amount of wheat to each village, assigning a local resident the duty to distribute it. This system, officials say, led to an unequal distribution in some places and total misappropriation in others. The district administration, therefore, decided to centralise distribution.

After the provincial government declared Tharparkar a calamity-hit area on September 5, 2018 and the latest phase of wheat distribution started, centralised points were set up at each of the seven taluka headquarters in the district. To ensure equality and transparency, distribution was not to be made randomly but according to a verifiable set of data. This is where the NADRA-prepared list came in. As things stand today, the distribution system has moved back almost full circle.

In any case, a single bag of free wheat provided once a year does not go very far in addressing the chronic problems of malnutrition, poverty and lack of access to water for both drinking and irrigation. Recurring drought in the district immediately wipes out whatever little impact such mitigation measures may have, says Ali Akbar Rahimoo of Aware. He wants the government to do something that sustains longer.

He also mentions two draft laws — one for devising a Sindh-wide long term drought management and mitigation policy and the other for the setting up of a financially and administratively empowered Thar Development Authority.

“These were submitted for presentation in the Sindh Assembly in 2014 but have not come up for legislation so far.”

2

Mohammad Shahzad’s orchard is shrivelling. The apples he is harvesting this year are small and withered. A consignment of 300 cartons that he sent to Multan fetched such a low price that it fell short of packaging and freight charges by 6,000 rupees.

Shahzad, a thickset clean-shaven Pakhtun in his thirties, is supervising the packing of apples for another consignment on a mid-September day in his orchard in Kawas union council of Balochistan’s Ziarat district. He is worried that this consignment, too, will not sell well.

He owns 500 apple trees. To irrigate them, he is entirely dependent on rains and snowfall which are both going down steadily in this part of northern Balochistan. Most parts of Ziarat district, for instance, have received little snowfall for the last five years.

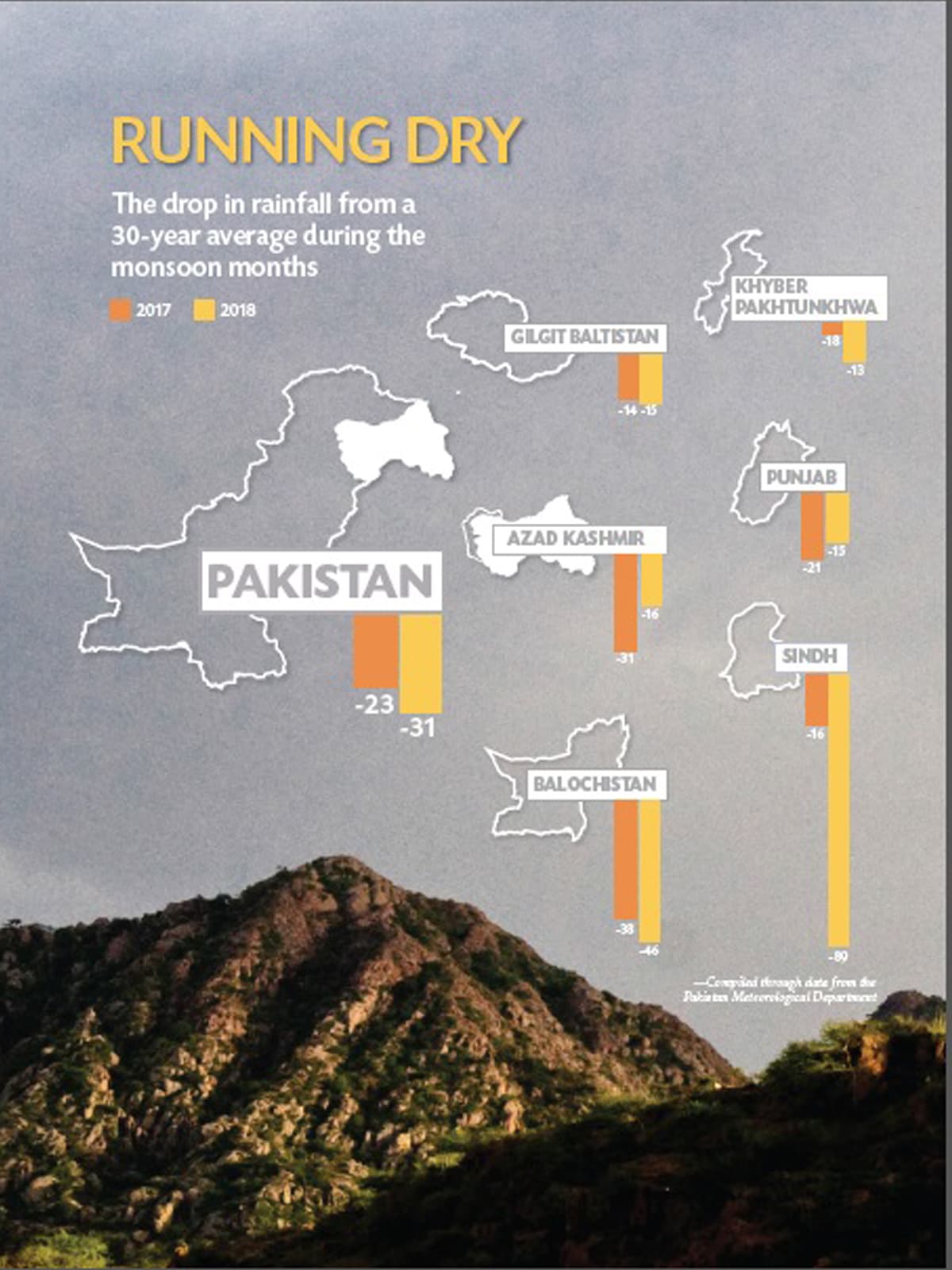

On the whole, Balochistan received 38 per cent less rainfall than its 30-year average during the monsoon months of July, August and September last year. In 2018, the decrease was even more steep — 46 per cent.

As a result of this drastic drop in the availability of water, annual produce in local orchards has gone down manifold. One farmer in Kawas union council has seen the yield of his 17 apple trees drop from 300 cartons four years ago to just 15 cartons this harvesting season. The quality of his apples has also gone down. He once made a yearly profit of 100,000 rupees. Now he is not being able to recover even his production costs.

Hundreds of other farmers in the high altitude northern Balochistan have experienced a similar decline in their harvest in recent years. Many of them have employed some desperate measures – such as purchasing tanker-supplied water – to irrigate their orchards with the hope that the next monsoon will bring better rains. They have only found out that this does not work.

Water tankers are costly – each costing a few thousand rupees – and are, thus, unaffordable to buy year after year but monsoon rains, too, have continued becoming drier. Those who do not have any capital to spend on procuring water have now left their orchards at nature’s mercy.

In early September this year, the entire 60-kilometre length of Ziarat valley along the Quetta-Ziarat road looks like a wasteland. Streams are parched, small man-made ponds are dry and withered fruit trees are visible as far as one can see.

Throughout the valley, steel pipes can also be spotted running up the mountains — sometimes several kilometres high. These carry groundwater to orchards at hilltops. Richer farmers are spending millions of rupees on extracting ground water with diesel-run pumps to irrigate their orchards.

Their costs are continuously soaring, though, as the underground water table goes down steeply since it is not being adequately recharged through rainfall and snow. Sometimes, they have to drill into the earth multiple times before they hit the dwindling water table.

The underground water table would not drop by more than a couple of metres during earlier dry spells, says Nasibullah Khan who works as a coordinator with the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) in Quetta. “It is now dropping by 50 to 60 metres annually,” he says.

Many hydrologists and government officials argue this drop should be treated as a clarion call to conserve water. One way to do so, they suggest, is to abandon flood irrigation techniques now prevalent all over Pakistan and adopt drip irrigation. Nasibullah, though, does not agree that drip irrigation can help save apple and peach orchards in Ziarat. “These trees need a lot of water,” he says.

Amel Khan, who owns apple orchards and grape vines in Pishin city and is also a graduate in agriculture research from the University of Agriculture, Peshawar, has a similar view. “Higher altitude grapes can be grown with drip irrigation but not apples, peaches or cherries,” he says.

A drip irrigation system, Amel Khan explains, is also expensive to set up. It requires heavy investment in putting in place a network of pipes and also needs constant maintenance and cleaning so that pores in the pipes do not get blocked. “Not every farmer can afford its cost.”

Retreating rains have also underscored the scourge of deforestation. Over the last three decades, people in Ziarat have mercilessly chopped trees for using them as firewood — perhaps because this is the only way they can keep themselves warm during the freezing winters that they have to endure every year.

The district was once known for its dense forests of juniper, a tree that, according to experts in forestry, grows only by an inch a year. These junipers are now vanishing fast.

Mozam Khan, who heads Ziarat’s district council, is acutely aware of the problem. “If the hills in Ziarat look barren, it is because of the excessive felling of trees,” he says.

The reduced tree cover is now having a perceptible impact on the amount of rain that Ziarat receives and the situation threatens to only get worse. “Without trees, there will be no rain and snow in the coming years,” says Mozam Khan.

To increase the number of trees in the area, he champions planting of trees that can grow faster than junipers. “How long can we live in the nostalgia for our juniper forests?”

Everything looks serene in Malik Azam’s courtyard on a recent work day. Labourers are moving about calmly, packing freshly picked apples. Not a voice rises above a low work-related murmur. After the azaan echoes from a nearby mosque, everyone lines up in a corner to offer prayers.

The peace is soon shattered.

Malik Azam appears from inside his house and starts yelling at the labourers. A burly Pakhtun in his early forties, he does not overlook even minor mistakes they may have made in the packing process. The labourers, who have come to this part of Pishin district near the Pak-Afghan border from Kandiaro town in Sindh’s Naushahro Feroze district, silently do as he bids them.

“Malik Sahib was not like this,” says a labourer later. Water shortage, and the havoc it has wreaked on his orchards, has made him so.

Malik Azam lives in Malikyar village — around 71 kilometres north of Quetta. Adjacent to his village is a water reservoir called Bund Khushdil Khan. It was built in 1901 by the government of British India and was declared a protected wetland, a Ramsar site, by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in the mid-1980s for being a winter home to migratory Siberia birds.

He has reasons to be upset. “I had 5,000 apple and peach trees a couple of years ago,” he says, “now I am left with only 900.”

In a conversation punctuated with abusive words, he alleges his orchard has been ruined because the Balochistan government failed to maintain Bund Khushdil Khan. This failure has resulted in a steep decline in the underground water table not just in Pishin but in the adjoining districts of Mastung and Quetta as well, he says.

The reservoir stores water flowing into it from a seasonal river called Pishin Lora that brings rainwater down from the mountains in the north. It did not store as much water in recent years as it has the capacity to store because of the provincial irrigation department’s negligence, Malik Azam alleges. Its banks are eroded at several places, he says, allowing water to drain into a desert to the west.

Saleem Awan, secretary of Balochistan’s irrigation department, acknowledges that the embankments of Bund Khushdil Khan need to be strengthened. His department, he claims, is working on that. It is also working on strengthening the embankments of Pishin Lora and its four main tributaries to protect their waters from flowing away from the reservoir, he says.

Prolonged dry spells are not uncommon in this part of Pakistan. Usually a rainless period lasts six years and, if Malik Azam is to be believed, Bund Khushdil Khan, with a capacity to store 15,000 acre feet of water, used to fulfil local irrigation needs for this enitre period. This time round, he says, the reservoir has run out of water in the third year of the dry spell.

Nasibullah of the IUCN does not agree that this has happened because of a negligent government alone. He believes the reservoir has dried up sooner than it should have because irrigation needs of the area have increased in recent times due to a rapid increase in agricultural activities. “If the current practice of tilling land for growing grains and fruits is allowed to continue, a time will come when the whole of northern Balochistan will have no water, even to drink,” he warns.

He explains how “something similar” happened in Quetta which once had orchards all along its outskirts as well as in its adjacent areas of Hanna-Urak. Now, he says, the underground water table in Quetta is extremely low and is also not fit for human consumption.

Hundreds of people from Ziarat, Pishin and Mastung districts travel to Quetta every day to work as manual labourers. Almost all of them were engaged in various agriculture-related activities in their home districts but drought has rendered them workless.

Yet, Awan does not agree that drought in northern Balochistan is so acute that this part of the province should be officially designated as a calamity-hit area — thus qualifying for urgent mitigation measures such as free distribution of grains and cereals. “Northern Balochistan experiences a long dry period after every 12 or 15 years. This phenomenon has persisted in this region for centuries,” he says. The only difference now, according to him, is that “climatic changes and a growing population are making the situation complex” to cope with.

Awan also likes to point out that there is no shortage of water in the province. Total availability of surface water in Balochistan, according to him, is around 21 million acre feet (MAF). Around 10 per cent of it – 2.5 MAF – comes from the Indus River and the rest from numerous seasonal and perennial rivers and streams in different parts of the province. But Balochistan has the capacity to utilise only 50 per cent of this water, he says. The rest, he adds, goes to waste, flowing into barren lands and being absorbed by the earth.

To be able to use this water gainfully, Awan says, around 100 small and medium dams are being planned across the province. The provincial government, according to him, will soon award a contract for building one of them — Mangi Dam in Ziarat. “This dam will provide drinking water to Quetta and will also improve the underground water level in Ziarat district.” Another 300 check dams will also be built in and around Quetta valley, he says. “These will improve the underground water table not only in Quetta but also in the adjoining districts of Mastung, Pishin and Ziarat.”

These are all long-term plans which may or may not materialise, depending on whether the government can find money to finance them. In the short term, Awan expects the ongoing dry spell to end as early as this winter. “[Northern Balochistan] will have normal to above normal rains and snowfall in the coming months.”

Sabzal Baloch, a farmer in Balochistan’s southwestern district of Kech, lives in a small hut. Built with mud bricks, its roof is supported by trunks of date palm trees.

Lying on a worn down mat (made of date palm leaves), Sabzal Baloch becomes nostalgic as he talks about drought. “Balochistan used to have an age-old underground water supply system called kareezaat but, unfortunately, most of these kareezaat have either dried up or collapsed,” he says.

In Panjgur district alone, according to a senior official in the local administration, around 70 kareezaat have dried up.

The destruction of kareezaat has left agriculture in southern and southwestern parts of Balochistan heavily dependent on rains and underground water. Since there have been next to no rains in these parts over the last six years or so, agriculture and livestock rearing have both suffered badly here.

According to the provincial government, rains have been below normal in 22 out of the 32 districts of Balochistan for the last several years, but six districts in the south and southwest of the province – Awaran, Panjgur, Kech, Gwadar, Kharan and Chagai – have been hit the hardest.

In Kech and Panjgur districts, successive crops have failed due to water shortage. Date palms and other fruit trees have died out and wild grasslands have all but disappeared. Bush and thorns have taken over where rice paddy fields once flourished.

Samiullah Baloch, a superintendent engineer of the irrigation department in Kech district, says the level of underground water has gone down anywhere between 50 and 100 feet in Kech over the last few years. This is mostly because local farmers are extracting groundwater in large quantities with diesel-run pumps and electric tubewells to irrigate their crops but the absence of rains is not allowing local aquifers to recharge.

Around 400 families from about 20 villages in Kech’s Dasht tehsil have migrated elsewhere, both because of drought and separatist violence, says Haji Fida Hussain Dashti who heads Kech’s district council. In Panjgur, nearly 100 families have lost all their livestock, forcing them to migrate.

Similarly, 70 per cent of the population has migrated from Kulanch Ambi village in Gwadar due to severe water shortages — as have the residents of many rural areas in Pasni tehsil. Drought has wiped out livestock at a very large scale, forcing people to migrate to Pasni town, confirms local assistant commissioner Captain (retired) Jameel Ahmad.

Jiwani town, in the southwestern corner of Pakistan, and Gwadar city have both run totally dry. The sources of drinking water closest to them, such as Akra Dam, also dried up a few years ago. The provincial government is spending 3.5 billion rupees every year to provide drinking water just to Gwadar city, claims Sana Baloch, a member of the Balochistan Assembly. Water is brought in tankers from Mirani Dam, 175 kilometres to the northeast of the city, by road.

Sana Baloch argues that this huge expense is unsustainable but complains that “no appropriate policy mechanism has been devised to cope with the ongoing drought in Balochistan” on a sustained and long-term basis. The province needs more than 3,000 small, medium and large dams, he observes.

“But the government is not doing anything in this regard.”

3

Mori Lasht village sits on a promontory on the right bank of the Chitral River, about 30 kilometres north of Chitral city. Standing here, one can hear faint echoes of hill torrents flowing into a deep gorge across the river but the village’s own farmland is sunburnt, parched and its orchards withered.

It was a small hamlet of a dozen or so mud-brick houses about 40 years ago and used to receive its water supply from a nearby stream. Some years later, the villagers dug up another canal on mountain slopes to get additional water from another stream called Istangol.

This led to an agricultural revolution. Barren lands were brought under cultivation and the village turned into a food and fruit basket. Its population also grew to over 150 households. Come 2018 and local farmers could not even sow their rabi (fall) crops due to the water shortage.

Farmers in many other villages across Chitral have not sowed their rabi crops for the same reason. In some villages, residents had to ration water to sustain farming.

For a district known for its silvery streams and glistening lush valleys, Chitral has been placed in “medium” category in terms of vulnerability to drought by a 2017 report prepared by the Islamabad-based National Disaster Management Authority. It receives little monsoon rains but that usually gets compensated by snowfall in winter — melting snow providing water for irrigation and drinking to almost the entire district. Last year, however, the district received very little snowfall which has resulted in water scarcity in most parts.

The amount of water flowing into Istangol stream, too, went down drastically. This put the residents of Mori Lasht face-to-face with those living in another village that the stream also irrigates.

“They told us not to use the stream water since it was insufficient to meet the requirements of both the villages,” says Haji Ghaffar Khan, a former local councillor and a resident of Mori Lasht. “After a lot of bickering, we gave in,” he says.

As a result, he fears, farmers in his village will not be able to sow their kharif (spring) crops as well. Almost everyone in Mori Lasht has sold their livestock already to cope with the financial consequences of failed crops.

Distraught villagers have protested for weeks recently, demanding the government do something to address their predicament. They even threatened to migrate to Afghanistan en masse — but all to no avail.

A prolonged dry spell is also ravaging agriculture and livestock in the arid expanses of Dera Ismail Khan and Lakki Marwat in southern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. The National Disaster Management Authority report states that the two districts are the most vulnerable to drought in the whole province due to their rain-dependent agriculture and drinking water supplies.

Haji Abdur Rashid, president of an association of farmers in Dera Ismail Khan, says drought has had a negative impact on sugarcane crop in his district already. While on one hand, less rains are causing distress to local farmers, he says, on the other hand, the construction of Gomal Zam dam in the neighbouring South Waziristan district is severing links between Dera Ismail Khan’s irrigation system and hill torrents — a major source of irrigation locally.

In Lakki Marwat, too, farmers are anxious. If there are no rains this winter, they may even lose the seeds they have already sown.

The Pakistan Meteorological Department – or Met Office – sounded an alert in September this year: Multan and Mianwali districts were facing a mild to moderate drought. Multan received around 60 per cent less rainfall than its usual average during the monsoon months of July, August and September. Mianwali received about 50 per cent less rain than it usually does during the same period.

They are not facing any water shortage — at least not yet. Widespread availability of canal water there is compensating for the decrease in rainwater.

Ikram ud Din, director of a drought monitoring centre at the Met Office, says the drought alert may be revoked if the two districts receive their normal share of winter rains. If these rains also remain below their long-term average or, worse still, do not materialise at all, that will spell disaster. This will affect the sowing of rabi (fall) crops – such as wheat, mustard and barley – and can also have a negative impact on wheat yield.

If Multan and Mianwali receive no rains in the coming weeks, seeds sown in rabi may also not germinate in many of their parts, says Muhammad Ajmal Shad, a director at the regional meteorological center in Lahore. The drought will then graduate from being a meteorological one to an agricultural one.

Additional reporting by Amel Ghani, Manzoor Ali and Masood Hameed

The writers are staffers at the Herald.

*This article was published in the Herald's November 2018 issue. To read more to the Herald in print.*