Among the so-called neurotics of our day there are a good many who in other ages would not have been neurotic — that is, divided against themselves. If they had lived in a period and in a milieu in which man was still linked by myth with the world of the ancestors, and thus with nature truly experienced and not merely seen from outside, they would have been spared this division within themselves.

– Carl Jung, Swiss psychoanalyst

When winter arrives, the village folk come down from the mountains to their villages, bringing back cattle fattened on the highland grass. Soon there will be snow, confining them to their homes. They will slaughter an ox or a goat and salt and dry its carcass — as part of Nasalo, their winter festival. This, along with fruit dried and grain harvested in summer months, will sustain them through a long, cold winter.

But before the villagers move into closed indoors, they must exorcise evil spirits that have moved in while they were away.

The spirits are quiet and secretive. From their hiding places, they are expelled through a rite of noise — villagers knocking walls and doors with a pickaxe or a rolling pin. Residents are not allowed to sleep inside their houses during exorcism because if they do, the spirits will possess them to stay on with them. The ritual done, the villagers have a feast of goli – bread rolled in butter – to declare their houses safe for habitation.

In mountain valleys of Chitral and Gilgit-Baltistan, communities are as disciplined and single-minded as ants. The clockwork of their lives is regulated by nature – through its bounties and scarcities, through the harsh and kind turns of seasons – as they work through summers to save for winters. Their naturalist outlook on life, and a mountain culture conceived and preserved in isolation from the rest of the world, hint at their region’s Shamanic past even when these communities have long embraced Islam. Largely symbolic than being an article of faith today, doman koh, or the rite of exorcism, is a throwback to an age covered in mists of time like the mountain peaks in clouds on a rainy day here.

Of late, though, the mountain folks have returned home to find that evil spirits have hardened themselves to withstand the ritual. Not only do they insist on staying, they demand a sacrifice far bigger than slaughtering a goat or a cockerel.

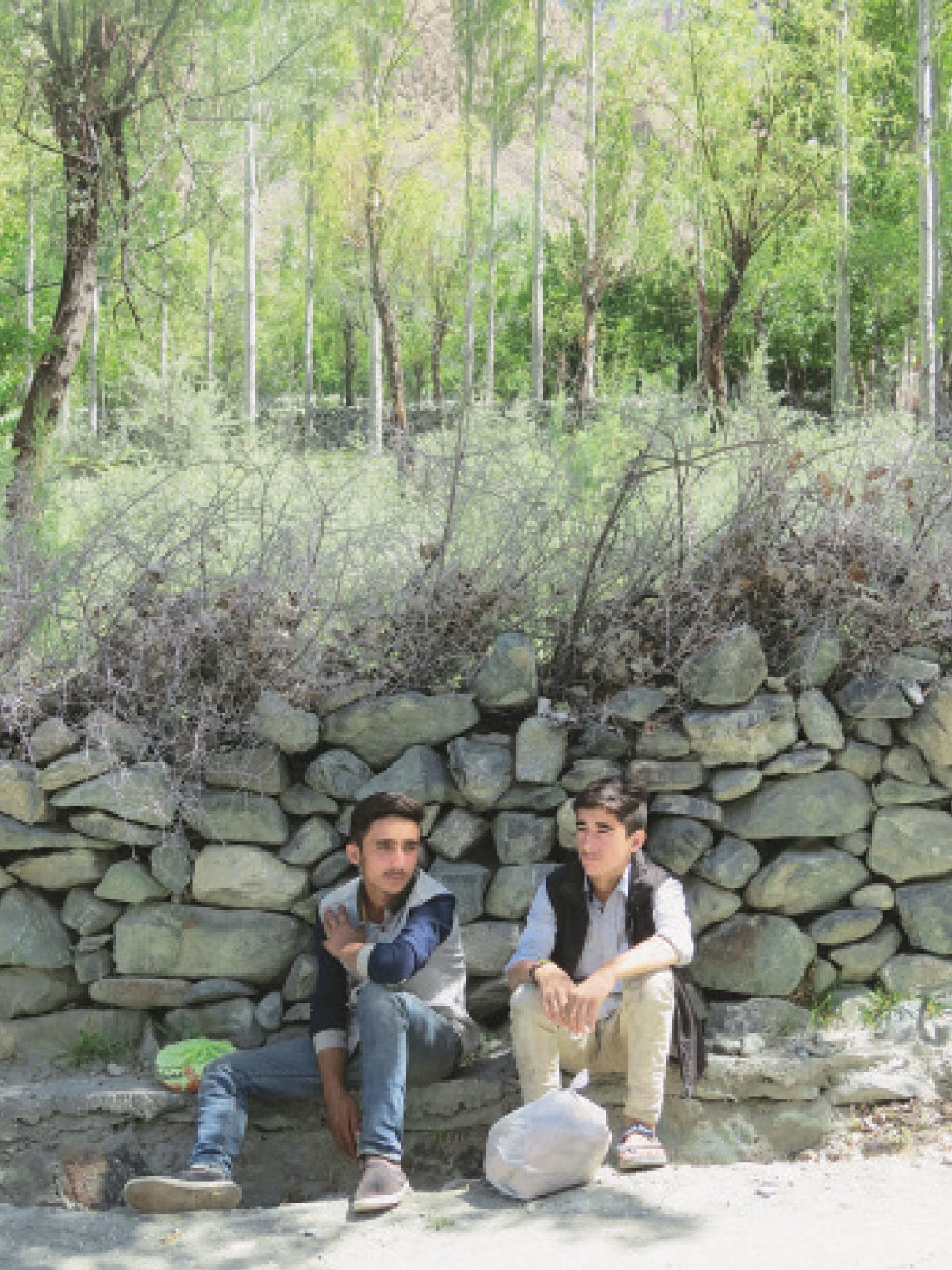

While the elders were in the mountains beseeching fairies for fecund cattle and bountiful harvest, their children left villages to get education in cities. They returned disabused of myths, divested of faith in fairies their forefathers bow to and seek counsel from in time of adversity. Drawn to the gods of globalisation – Oracle, Nike, Hermes, Mars: brands, not deities from mythology – the children have become split personalities, torn between an ancient world and a new one.

As the culture, festivals and traditions that give the locals a sense of self and sociocultural identity die so do the bonds that hold mountain communities into a cohesive whole. As those bonds die, they leave a curse behind. The locals find themselves amidst a zone where the self stands on shaky ground between the solid world it once inhabited and the virtual one that lacks a core.

The self stands lost. And there is no help from fairies in the face of an onslaught from fiends – the relentless, faceless forces unleashed by modernity, globalisation, sectarianism, radicalisation and state oppression – that snuff all hope for self-realisation.

At the altar of these raging demons, the mountain communities must sacrifice their own lives and those of their children. With a cockerel, a goat, a prayer, they cannot be allayed.

When life blooms in spring, they go to die.

You would not know it from the young hopeful faces of children in school uniforms, saddled with colourful bags and holding hands as they walk to school from home through poplar-shaded streets.

You would not know it from the retired soldier, feather-crest in his pakul cap, who stops to buy muntu – dumplings made with onions and mincemeat – from a shop along the road; or from the young man wearing a jeans folded half way up his shins and a red T-shirt, leaning forward on the seat of his motorcycle, who stops along the way so he can text on his phone. You would not know it from the shadows on the tree-lined street leading up to the river, from the wind that suddenly rises in the evening as a dying sunlight lingers over peaks surrounding the valley, or from the blazing, bright afternoon that leaves eyeballs scalded, hot and itching from sunlight.

Neither would you from the child who laughs as he runs across the street, chased by a young father who plants his rosy cheeks with kisses, laughing as he tickles the child’s face with his own.

You would not because Ghizer has valleys redolent with the scent of bairer trees. Its villages resonate with the song of mayun, the golden oriole, that echoes in the small hours before dawn and seems to celebrate nature’s bounty: “the apricots are ripe, the apples are rotten,” is how local residents interpret its fragile notes.

These, as anyone would tell you, are the sights, sounds and scents of eternity. Of life as it always was and always will be — thriving and exuberant.

You only know it from a ping that makes Sharafat Ali, an Ismaili social activist who works with the youth, pick up his phone and announce anxiously: another suicide.

You do not want the news of another suicide, not here in Gahkuch town, the district headquarters of Ghizer. First, because if life and death are mutually exclusive, how can they coexist in the same space with the same intensity? Second, you have come to dread suicide as if it is a madness you might also catch.

The news reinforces observations, speculations and fears you are out to challenge and hopefully lay to rest, hoping against all hope that Ghizer’s reputation for a high rate of suicides is wrong or, at least, blown out of proportion. That the river snaking through the heart of this paradise is no serpent; that there is no worm eating into the vitals of life here; that there is no tragedy lying in wait for the village folk, like the cracks from several earthquakes in the walls of their houses that perhaps would not survive another.

Sharafat Ali’s phone receives a picture: a sturdy young man with a clean crew cut and bulging muscles that strain against the tight sleeves of his T-shirt. Merely 25. A life cut short, now frozen in a picture of a hopeful face. A hope that is lost.

Who else lost hope when he died — a parent, a spouse, a sibling, a friend?

They say suicide in these parts has become a fashion, a rage for the copycat youth. He, too, is a role model for them. Young. Handsome. Dead.

The only consolation is that he is not from Ghizer. He is from Hunza. But how is that a consolation? Is it not ironic that Hunza, a place where the old are known to live to ripe old age should also have a reputation for the young killing themselves prematurely?

From Buni town in Chitral to Yasin valley in Ghizer, young men and women in Pakistan’s north are choosing death when they should be alive with ambition and hope. In Ghizer, more girls than boys are committing suicide; in Hunza, it is the boys. Local settlements, scenic and placid on the surface, have suicide points just like they have picnic spots or lover lanes.

Every suicide has a story and you wonder about the story of the young man whose photo Sharafat Ali has received.

In Ghizer, there are 203 stories of those who have committed suicide between 2006 and 2017. Everyone here has a story of a suicide to tell, sometimes even two or three. Of a brother who shot himself, of a sister who jumped into the river, of a cousin who took poison. It is not unlike the time when terrorism peaked in Pakistan and in your hometown you knew someone – a friend, a family member, yourself – who had survived a suicide bombing or lost someone to it. It is that random but it is also different.

Suicide bombers die for what they believe is a cause. Those who commit suicide have none to live for. The motives of suicide bombers may be “altruistic” — as defined by French sociologist Emile Durkheim whose suicide theory is considered seminal in sociology. They think they are dying for a shared ideal or a collective purpose that is larger than their own lives. A suicide is “fatalistic” when in reaction to oppression from the state or the system, or “egotistic” when an individual commits suicide because he or she fails to integrate in a social set-up.

In Chitral, people report a surge in suicides every spring — between February and April. “It must have something to do with a psychotic disorder that tends to aggravate around spring,” says a local associate of the Aga Khan Rural Support Programme, a non-governmental organisation (NGO).

A young doctor in Ghizer, who routinely performs autopsies on those who have committed suicides or treats suicide survivors, confirms the same. The local season of suicides, he says, follows international trends. Change in seasons and effects of light on hormones, he says, prompt suicides between April and June in northern Pakistan — just as they do in the rest of the world.

But it is August and the young in Chitral are still killing themselves for scoring low in exam results. In Ghizer, too, they are dying of reasons other than seasons and sunlight.

On a recent night, knots of young boys lean on the railing of a bridge over the Ghizer River, looking down, casting long shadows under the lights. From below the bridge rise the roar and the rattle of the river, wild waves rippling like scales on a serpent.

Night after night, young men in Ghizer are drawn to the river like moths to the lamplights on the bridge. To some, it is the river’s soothing sound that strangely deepens the night’s silence. To others, it is a call.

In Chitral, they say do not go near the river when it is the season for grapes to ripen because the river calls for blood then.

Her name was Aasia. She was 23 and married to a man in Ashrait, a village near Chitral city. Her husband, a distant cousin of hers, wanted to keep her with him but Aasia and her mother-in-law did not get along. For nearly a year, she intermittently lived with her father while the two families tried to reconcile but her mother-in-law would ask her to leave every time she moved back into her husband’s house. Through all this, she had a daughter who did not live long.

Aasia got divorced three months before she walked to the river with her six-year-old sister. On that day, she told her aunt, with whom she was staying in Chitral city, that she wanted to go home to her father. Out on the road, she stopped a car and told the driver to take her to the river bridge. “We are going to a park there,” she told him.

There Aasia flung herself into the river, leaving her sister standing on the bridge. A man found her there, lost and crying.

“Those who intend to commit suicide go to the river because it is easily accessible,” says Inayatullah Faizi, a college principal in Chitral. “Since they are in a state of anguish, the river is the first place that comes to their mind. They do not have to ask for money to buy pills or poison or to seek other devices for suicide.”

The river is there. And it calls.

The Chitral River has its origins in Chiantar Glacier in Broghil Valley, high up in the northwest where Chitral and Gilgit meet the Wakhan Corridor in northeastern Afghanistan – a narrow strip of land that extends to China and separates Tajikistan from Pakistan. From the river flow 32 streams for 32 valleys of Chitral, says Faizi, so that each village is settled around a stream. River is the locus of all life in these settlements — some as ancient as 600 to 800 years.

Poets in the region see the river as an obstacle to love, with the lover and the beloved living along its separate banks. “Oh beloved, your abode is on the other side of the river and there is no boat to cross it,” says one of them.

Another, Mirza Muhammad Siyar, whose verse people know by heart, uses the river water as a symbol of life. “I am near death in your love, like a fish out of water gasping for air.”

In love and then divorced, Aasia must have been a fish out of water. Is that why she jumped into the river?

On a recent night when a cold rain is falling over the valley, I go out to trace Aasia’s footsteps. The bridge over the river is a mere suggestion of itself, a black brushstroke on the inky canvass of the night. Yellow and black railings on its sides glisten wet with raindrops. Below, the river flows invisible. Its rustling sound is like the wind echoing through the valleys: it follows you. You can hear it no matter where you are — in mountains, villages or towns.

Ghizer valley is at its most enchanting in the mornings, with the mountains covered in mist. Think ravens calling, think pine smoke drifting over houses, think the song of mayun, think maple trees swaying and think the rustle of discarded wrappers driven by wind on the river’s bridge.

On the phone all morning, Sharafat Ali finally gets to trace Syed Noorul Hussian who has been out in Ishkoman valley – recently in news for a glacier melt that created an artificial lake and inundated an entire village, like the one in Attabad, Hunza, in 2010 – where the communication network is patchy. Hussain’s Safety Life Organisation works on suicides — monitoring, documenting and creating awareness about them.

Given the number of suicides happening in the valleys of Ghizer, he has his hands full. The backseat of his car is littered with papers. It looks as much like an office as a means of transport. He is always on the move on bad roads between remote villages to meet families of those who have committed suicides. They are often reluctant to speak because of the stigma or due to causes best not spoken of.

“Versions of each story keep changing. I had to interview a family 10 times to get to the heart of one story,” says Hussain. Once he phoned a family 17 times to find facts and was beaten up for that. A letter from the home department of Gilgit-Baltistan’s regional government that shows him as a government monitor saved him from police action.

“Finding the truth is especially difficult with reference to women who commit suicide,” he says. “Families hide the factors that lead to their death. This also hampers police investigation.”

Hussain lays out papers on a lawn table. These carry data on the number of suicides in different valleys of Ghizer district: Punyal has had the most suicides — 76; it is followed by 50 cases in Yasin, 32 in Gopis, 26 is Ishkoman and 19 in Phandar. More women – 107 – than men – 96 – have committed suicide in the district over the last 11 years. Students between the ages of 11 and 20 are the largest group among them, followed by married people.

Of all the cases recorded by Hussain, 102 have been deemed as definite suicides. The remaining 101 have been registered with the police for inquiry and investigation due to an element of doubt about the circumstances of death. Many of these may also turn out to be suicides, confirming what Hussain’s data suggests: that suicides are happening in Ghizer in numbers far greater than homicides.

In Gopis tehsil, for instance, there have been 28 confirmed suicides as opposed to only four cases being investigated as murders. In Yasin tehsil, murder is suspected in just five of the 50 cases. For Punyal, the ratio of suicides to suspected murders is 73:3. It is 24:2 in Ishkoman.

Punyal tehsil – where the district capital Gahkuch is located – is the most developed part of Ghizer district. Literacy rate here is very high. It is also where the number of suicides is the highest in the entire Gilgit-Baltistan region. Within Punyal, Gahkuch has seen more suicides – 24 – than the rest of the tehsil. This trend persists in all the five tehsils in Ghizer: their headquarters have higher suicide rates than the rest of them.

Hussain’s own sister-in-law, Nadia, attempted suicide recently. She lives in Birgil, the last village in Punyal before Ishkoman, a valley on the Pak-Afghan border, begins. The road to Birgil is rough, getting rockier as it moves away from Gahkuch. The terrain is sandy and grey. Occasional settlements can be spotted along a river. The mountains seem to be pressing in on the valley.

Along the way, the road suddenly throws up a stark metaphor for social change in these isolated mountains: two young men pulling a cow. Alone in the middle of nowhere, they are dressed in jeans and T-shirts; sharing a red bottle of an energy drink like city boys anywhere, they tug along that constant, universal fixture of pastoral life — livestock.

“We are surrounded by mountains. We live in a box,” says an Aga Khan Rural Support Programme official in Chitral city where the rate of suicides has alarmingly spiked in recent months and years. This isolation, according to him, is geographical, ethnic, cultural and perhaps even religious. “If a young person in Punjab’s Sargodha or Sialkot district returns home after studying in Lahore, he may find employment locally. Even if someone educated from a village in Punjab does not want to do farming, he can easily go to a nearby city. What has Chitral or Gilgit-Baltistan to offer for someone educated?”

This is why a girl from Hunza is “forced to collect firewood” even after she has done her PhD.

Birgil, with its wheat fields, mulberry trees and women tending cows, is a pleasing sight. Nadia lives in a small two-room house that has its own vegetable patch, a grapevine and poppy plants with fragile orange-red flowers. She is 22 and edgy.

She seems to cry and smile simultaneously as she speaks about her suicide attempt, not making eye contact. The varnish on her nails is cracked and she has a distracted look about her. “I mostly sleep,” she says, “because I keep thinking when I am awake.” Thinking hurts her head.

Nadia has friends but she mostly stays to herself. She says girls in her village have “tense lives” because brothers and fathers are always angry with them. “It is the immediate family that adds most to their distress,” she says.

Nadia could not continue studies “because of stress”. She loved a cousin who is working in Dubai. He told her he would marry her but his parents did not want him to. Sometime ago, he came to Pakistan to get engaged to another girl without telling Nadia but he continued talking to her over the phone, giving her hope. “I could not tell that he was lying because I was stressed out all the time.”

When Nadia found out about his engagement, she told his fiancée about her own associations with him. It led to a family dispute. When he would not talk to her anymore, Nadia took a bottle-full of pills. “[Dying] was better than listening to all the talk behind your back,” she says.

Does she regret taking pills? “I do not regret anything. I did not do anything wrong.”

Gilgit-Baltistan, except its Diamer district, has a reputation for educating girls, especially villages and towns with an Ismaili population. Women move freely about; they go to schools and run businesses. In Chatorkhand, the headquarters of Ishkoman tehsil, there are markets for women, run by women. Travelling in the mountainous outback between villages, it is not unusual to come across a shop with a woman at the counter.

On the way back to Gahkuch from Birgil, Hussain takes the car over a rattling, swaying suspension bridge on the Ghizer River. On the other side of the bridge is a valley with tall poplars lining a potholed dirt road where the car sputters and stalls. He leaves the vehicle and walks to a nearby village, Hatoon, where a girl recently attempted suicide.

There is little that sets Hatoon apart from other scenic villages in the district. Its stone-walled streets are long and winding, lined by poplars, willows and a tree the locals call bait, its leaves used as fodder for goats. Through a narrow dark street, shaded by mulberry and persimmon trees and dank from a stream running along its side, Hussain walks up the hill anxiously, led by a local young man, to the girl’s house. He is not sure if her family will want to talk about her attempted suicide. The street is quiet, except for distant voices of cows mooing, goats bleating and people talking behind low stonewalls and ancient wooden doors.

The man who opens the door is the girl’s uncle. He says she has gone to another village and shuts the door politely in the face of Hussain’s guide. That evening back in Ghizer, the body of a woman from Hatoon is brought to the district hospital for autopsy.

All the time Hussain was out looking for the girl who had survived a suicide attempt, another woman in the same area was planning to take her life.

One wonders what her story is. But the dead tell no tales.

Early this summer in Hunza, six boys from Passu in Gojal valley go out wearing roller-blades, lurching back and forth along the Karakoram Highway like the traffic headed for China.

All of them have stayed in cities like Rawalpindi, Lahore and Karachi. One is a graphic designer, another a chef. Others are still in colleges and universities. One of them is a Marxist, another an artist.

They stand along the roadside in Passu, in the shadow of a mountain. “In cities, there are opportunities and facilities,” says Maqsood Arif, the graphic designer. Others around him nod in agreement. “But we cannot stay there. We have to come back here and work for our community. It is part of our vision — to contribute to the well-being of our community.”

You find tradition ascendant in Ghizer. In Hunza, it is somehow the enterprise — focused on tourists, restaurants, eateries and bakeries. It is not enough, however, to keep the young – educated, skilled, idle and bored stiff – engaged even when they are trying out all kinds of small initiatives. Their dreams are always on the cusp of realisation but never fully realised because they need a market to flourish and Gilgit-Baltistan has none, tourists and mountaineers becoming fewer each year for reasons of security. So they go out, wearing roller-blades, to kill time — and sometimes to kill themselves.

On the night Inayatullah went to hang himself by a tree outside his house, he had sat late editing selfies he had taken with friends that evening in his picturesque village, Khyber, in upper Hunza, known for its successful ibex conservation project. His mother found him dead at six in the morning. That was in June this year. In July, another young man killed himself in the same village.

In village after village, there have been many cases of suicides recently and the trend is on the rise. “We have had cases of suicides but they were always of women,” says Sher Afzal, Inayatullah’s uncle. “In the last 20 years, the trend has shifted to boys.”

Inayatullah’s family is sitting in a large room built in the traditional Ismaili manner, with several pillars signifying the Prophet of Islam (may peace be upon him) and his family members. It is the sixth day of mourning with relatives still coming in for condolences.

“Nobody attempts suicide on a whim,” says Afzal, explaining why Inayatullah, 25, chose death over life. “The minds of the youth are etched with the belief that the world is an ideal place. When they get a jolt to their belief in the fairness of the world, it acts like a kindle to the fuel,” he says.

In Inayatullah’s case, the trigger came from the arrest of his father in China. He was close to his father who had worked as a contractor on the Karakoram Highway. After he lost the contract, he started working, like many others in the area, as a courier of goods to Sost, a dry port town on the Karakoram Highway, and onward to China. On November 9, 2015, he took a consignment to China that had cream jars full of heroin. He was given a prison sentence of 10 years.

His family has not heard from him. Their only contact with him is through a cousin of his who is also in China. They went to the Chief Minister of Gilgit-Baltistan, to the Prime Minister of Pakistan, the Chinese Embassy and to the media. There was no hope from anywhere.

Inayatullah worked for the Chinese on a construction project on the Karakoram Highway in Abbottabad. When he went on leave to come home this summer, he was upset about his father but nothing about him suggested suicidal tendencies.

There was a spike in suicides between 2000 and 2003, says Israruddin Israr who works for the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) in Gilgit. A research conducted by Aziz Ahmed, Sultan Rahim Barcha and Murad M Khan in 2009 speaks of a similar trend. Their paper, Female suicide rates in Ghizer, says that 49 women committed suicide in Ghizer district between 2000 and 2004. The numbers increased in 2010 and reached alarming proportions in 2017 when 12 to 15 suicides were reported in Ghizer in the month of May alone.

“Where most cases are concentrated in Ghizer, other areas like Gilgit, Gojal, Baltistan and Diamer follow closely,” says Israr.

But contrary to the popular perception that suicides in Gilgit-Baltistan started in the 2000s, Samina Sher and Humera Dinar of the department of anthropology at the Pir Mehr Ali Shah Arid Agriculture University, Rawalpindi, claim in a research paper that it is a much older phenomenon. They quote a newspaper, the Ghizer Times, as saying that 300 cases of suicide were registered in different police stations of Ghizer district between 1996 and 2010.

Several research reports show that suicide trends in Chitral are identical to those in Gilgit-Baltistan. They are highest among students aged 13-20, followed by married women who have had bad relationships with in-laws.

A 2016 study, Trends and Patterns of Suicide in People of Chitral, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan conducted by Zafar Ahmed and his associates and published in the Khyber Medical University Journal, said suicide was common among individuals aged 20-24 in the district. In just three days — between 7 and 10 August in 2018, seven people committed suicide in Chitral; five of them were students unhappy over their result in the secondary school certificate exam. In the first four months of 2018, the district had 22 reported cases of suicide — 5.5 cases per month on average.

Even earlier, the situation was bad. Chitral’s District Police Officer Mansoor Aman says there were 64 suicides in Chitral city between 2012 and 2017. The number of murder cases for the same period was 36. “The district’s population is 450,000 — the size of an area under the jurisdiction of one police station in Lahore. For a population of this size, it is an alarming trend.”

In the picturesque town of Buni, headquarters of upper Chitral district, a police officer says there is no other crime there but suicides. Two nephews of Bibi Ara, a nurse in the district hospital of Buni, both brothers, have committed suicide. The elder was 25. The younger was a fourth year medicine student at the Aga Khan University in Karachi where he killed himself.

People’s understanding of the crisis remains superficial though. Their explanation of something as inexplicable, and complicated, as suicide borders on the resigned and the casual.

Both Aziz Ali Dad, a Gilgit-based sociologist and commentator, and Israr, who take personal and academic interest in the issue, say the research on suicides has failed to look below the surface. Given the cocktail of causes, they emphasise the need for qualitative, inter-disciplinary research led by experts who will ensure an ethnographic approach to understand and address the issue.

Samina Sher and Humera Dinar, in their research paper, titled Ethnography of Suicide: A Tale of Female Suicides in Ghizer and published in The Explorer Islamabad: Journal of Social Sciences in 2015, cite various reasons for suicides among women. They note that marital and family relations, divorce, depression, disempowerment in decision-making, lack of freedom, academics, mental illness and demand for male child – in that order – are the reasons why women in Gilgit-Baltistan are killing themselves.

Women also get depressed from long winters when they are confined to their homes. Drug addiction is another silent killer. Iskhoman, for instance, has an opium problem, as does Ghizer. Men take drugs and sell lands to feed the habit. When they cannot look after their families, they commit suicide.

There are as many reasons as there are suicides.

II

To commit suicide, from Gilgit to vanish,

Is preferable by far to this life we lead. —Jan Ali, Shina poet

Raja Sher Jahan initially comes across as an opinionated person. A government official, he speaks with the vehemence of someone who knows what ails the mountain communities. In Islam, he says, suicide is haram (forbidden). “But when it happens, parents and families create circumstances that make it appear halal (kosher).”

As Muslims, he says, mothers and fathers should condemn the suicides of their children. “There should be no funeral for a person who has committed suicide, no matter what his or her sect — Ismaili, Sunni, Shia or Noor Bakhshi,” he says referring to the members of four Islamic sects living in Gilgit-Baltistan.

On the other hand, says Jahan, whenever there is a suicide, people converge on the house of the dead person due to close social networking. “Instead of grief, it becomes a celebration. This could develop a psychology of suicide among impressionable children who see this all around them.”

In Gilgit, Dr Aziz Ali Dinar, a member of the Ismaili Tariqah and Religious Education Board, voices a similar concern: “In the last two years, whenever a suicide occurs, it sets off a chain of occurrences in a family, a tribe, a village and a community, no matter what the sect of local residents. It is like a madness that is contagious.”

Could it be that something in the structure and culture of the community acts as a catalyst for suicide?

Since most suicides happen among local Ismailis, the common perception – albeit biased in a society deeply divided along sectarian lines – is that the members of the sect have moved away from religion. This, many people argue, has led to a spiritual void among Ismailis. Suicide is just a manifestation of that.

Ismailis are liberal, yes, but they are also more tightly-knit than the members of other sects here. Their jamaat khana – the house of the community – is more than a place of worship; it is at the heart of community affairs, a locus for strengthening identity and facilitating intellectual and social development of its associates. Durkheim, the French sociologist, viewed such religious affinity as a source for social cohesion that would decrease the likelihood of suicide.

Then there are projects run by the Aga Khan Development Network, an Ismaili organisation, in education, healthcare, agriculture and disaster management — seen inside and outside Gilgit-Baltistan and Chitral as community development models fit to emulate. These have also played a role in raising awareness about the need for social integration among local residents.

Still, many people often blame the very work of the Aga Khan Development Network as a major reason for suicides. Its projects have brought about a social change without ensuring corresponding opportunity for self-realisation, goes the argument.

Others say this is an unfair argument. In a region where the state has had little interest in socio-economic development – except in projects linked to the recently launched China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) – could one blame a humanitarian organisation for filling the gap?

People in Gilgit-Baltistan and Chitral often talk about how their regions were long kept in isolation by state apathy, distances and geography. Valleys like Ghizer and those further up north were long cut-off from even Gilgit city, leave alone the rest of Pakistan.

This changed with the recent lifting of the curtain through extensive telecom coverage, proliferation of media and the awareness it brings with it and, of course, education and the exposure to other parts of Pakistan it afforded to local residents.

Northern Pakistan saw a lot of development activity during General Pervez Musharraf’s regime. He was dazzled by the Northern Light Infantry’s impressive show in the Kargil operation in 1999 and grew close to the region where mountain men have served gallantly in armies, including that of the British whose annals speak highly of their soldierly heroics. In post-9/11 Pakistan, when Musharraf grew increasingly paranoid about his safety, he inducted men from the Northern Light Infantry in his security corps.

A bridge over the Ghizer River, a modern landmark, is part of a road network that Musharraf built. He also started work on the Lowari Tunnel, the lifeline of Chitral, in 2005 to connect the remote district to mainland Pakistan. This helped him win over hearts and minds. His party, the All Pakistan Muslim League, won a National Assembly seat from Chitral in the 2013 elections, the only one it could secure in the entire country.

The physical communication infrastructure, along with access to information technologies, opened up Gilgit-Baltistan and Chitral to globalisation, to modernity and to market forces that celebrate individualism and competition. The insulated tribal mountain communities built on collectivism and mutual support have been unable to cope with these developments. “Obviously change happens fast when there is education and a communications revolution,” says Dinar. “People here were not ready for that.”

Local residents earlier knew everyone in their own village and those in the next; absence of roads and bridges required them to stop and spend time in places that fell on the way in their travels. Now highways have people bypassing villages. Sociocultural bonds are coming unstuck with this.

But even before the 2000s, there were at least two major waves of change that transformed the sociocultural dynamics of northern Pakistan. The First Wave came in 1947, when Gilgit-Baltistan and Chitral became part of Pakistan.

“Before 1947, the region had its own languages that shaped the local cultural idiom. Those languages were formed in isolation from the rest of the world,” says Farman Ali, an Islamabad-based politician from Hunza. “With independence came Urdu. Since it was the official language of Pakistan, you could not conduct business with the rest of Pakistan without communicating in it. This put local languages such as a Burushaski, Balti, Shina, Khuwar and Wakhi out of currency and then stunted their growth.”

In Gilgit-Baltistan’s and Chitral’s oral culture, these were not just languages, they formed what Dad calls the “cultural vocabulary” of these regions.

Since these languages are not taught in schools locally and they do not have standardised scripts in which they can be written and transferred to the next generations, a common cultural vocabulary that informed people’s world view and their understanding of life and nature was lost, says Karim Madad, an Urdu instructor at a government college in Ghizer. Consequently, a sociocultural transformation or fragmentation – depending on how one looks at it – set in, creating a split in the region’s character and psyche.

Also, according to Farman Ali, Gilgit city was a common market for people from Hunza, Chitral, Kashmir, Xinjiang, Afghanistan and Central Asia before 1947. “The mountain milieu was enriched by travelers and stories of the Silk Road that contributed to its culture,” he says. After Pakistan came into being, Gilgit-Baltistan became a strategic region due to its location at the confluence of India, China, Afghanistan and Pakistan and was, therefore, closed to the very influences that had created its culture.

“The indigenous sources of self in Gilgit-Baltistan have dried up and the individual is invested with ideas and a cultural vocabulary that do not help him or her make sense of self,” Dad once wrote in the English daily, The News. “Such is the situation that the new generation of Gilgit-Baltistan can easily explain the psychology of African hyenas, but are oblivious to the social dynamics in their own hamlets or neighbourhoods.”

Even when palpable inside, the sociocultural change under the First Wave was still invisible to outsiders. The so-called “Northern Areas” were made exotic by their remoteness from and unfamiliarity to the rest of the country except in the context of tourism, mountaineering and, yes, dry fruits. They were only integrated into the administrative structure of Pakistan in the 1970s. Even after that, Gilgit-Baltistan and Chitral were administered for a long time under a black British-era law, the Frontier Crimes Regulation, which they shared with large parts of Balochistan and the tribal areas on the Pak-Afghan border.

These political changes still did not change the local economy much. Before the 1980s, people in Gilgit-Baltistan and Chitral lived off the land. The relatively educated among them opted for government service. Along came the Second Wave.

In 1984, the Aga Khan Rural Support Programme came to the region. It brought along with it a culture specific to NGOs. “Fresh graduates were paid high salaries and material acquisitions became status symbols. With it came competition and corruption because government officials, earlier content with their earnings, started aspiring to a high life,” says Farman Ali. “This culture … created a socio-economic dissonance.”

This is when the youth first started committing suicide after they could not get what they aspired to, he says.

But why the young? Because even back then the youth were educated, courtesy of the schools opened by various organisations linked to Aga Khan, the head of the (Nizari) Ismaili community.

The first school was opened in Gilgit-Baltistan in 1905, says Sharafat Ali, the Ghizer-based social activist. Soon after independence, Aga Khan Diamond Jubilee schools were built in the region. Initially they were all boys’ schools. In the late 1980s, the Aga Khan Rural Support Programme set up two academies for girls in two Ismaili-dominated areas, Gizher and Hunza.

The Aga Khan Education Service now runs 107 schools in Gilgit-Baltistan and 58 in Chitral. In addition, there are five Aga Khan higher secondary schools and more than 50 community schools in the two regions.

These institutions have revolutionised education, having increased literacy rates by leaps and bounds. The 2015 Annual Status of Education Report, generated by a civil society initiative, says 85 per cent of all children in Gilgit-Baltistan are enrolled in schools as compared to the national average of 81 percent. Education rankings for 2017 prepared by a foreign-supported advocacy and research project, Alif Ailaan, placed Gilgit at 36, Ghizer at 41 and Chitral at 46 out of 141 districts in the whole of Pakistan.

Where these educational developments have truly left a mark is female education — save in the Sunni-dominated Daimer district. In Ghizer, female enrollment rate is as high as 98. As remarkable as this leap has been, it uprooted students from their cultural context.

In the 1990s, says Farman Ali, schools introduced a westernised education system — with well-trained teachers and English as the medium of instruction. Girls and boys from villages suddenly had access to education that gave them a modern outlook on life and the world even though the places they lived were still tribal, pastoral and patriarchal.

Emphasis on education and academic excellence has also led to intense competition to excel in exams in order to enter higher education institutions. Come exams or results and many children choose death rather than to countenance failure — hence the high rate of student suicides.

While the young are dying of suicide, the old die of salt. Consumption of salty tea is causing heart attacks among people aged between 50 and 65, resulting in a big death toll, says Abdul Rashid, a resident of Passu town in Hunza. Sodium chloride, then, is perhaps a bigger killer.

Suicide? It is only a symptom of a bigger malaise.

The crowd at an Iftar party is almost entirely young. There is still time before the fast is broken so guests sit in chairs laid out at the pavilion of an open air restaurant in Gilgit city. The venue commands a view of the Gilgit River as well as of a road that leads to the Karakoram International University – the only one in Gilgit-Baltistan – set up in 2002 under Musharraf’s rule. The river during twilight looks like a living entity, its shiny water rippling and eddying around in thick waves.

In the restaurant’s courtyard, young men mill around, ushering in guests towards Nawaz Khan Naji who stands up to receive them. He is a member of the Gilgit-Baltistan Legislative Assembly from Ghizer but he is less of an elected politician this evening and more of a veteran rebel.

Naji and his friends formed the Balawaristan National Front in 1992, seeking autonomy for Gilgit-Baltistan. They claimed the state of Pakistan was attempting to alter the demographic profile of the region, reducing the indigenous people to a minority.

Among the guests at the party is a young man who works with a private telecom firm after having received a master’s degree in business administration from the Dadabhoy Institute of Higher Education in Karachi. He returned to Gilgit in 2014 and has been applying for a government job since then. “The private sector here is zero,” he says, “so everybody competes for government jobs.”

If there are three vacancies, he says, 5,000 candidates turn up. “Many students from Gilgit-Baltistan who studied with me are still jobless which is why many students here commit suicide.”

Whatever government jobs are there, claims Naji, they go to people on sectarian basis, not on merit. He then offers a political perspective on suicides: if you do not get what you want, if you have no power over the system, you either kill yourself or become a rebel.

A lawyer based in Gilgit-Baltistan advances a similar argument when he says that questions about the status and identity of Gilgit-Baltistan within Pakistan are, indeed, the source of many factors that act as catalysts for suicides and nihilistic tendencies among local people. Like the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (Fata), he says, Gilgit-Baltistan is in the stranglehold of forces of coercion, at work to disempower the region’s residents. “Our problem is not suicide but the environment which forces it. It is lack of social security, it is lack of governance and it is our status which has put our region and our youth at a disadvantage,” he argues.

In recent years, Gilgit-Baltistan has seen arrests, torture, harassment and use of blasphemy as a tool to silence human rights activists. An Awami Workers Party member, Baba Jan, is in jail for life for demanding rights for the people displaced by a 2010 landslide in Attabad. In July 2018, the region’s government added several dozen activists, political workers and religious leaders to a terrorism watch list.

The state’s paranoia and the people’s disaffection in Gilgit-Baltistan evoke Balochistan, Swat and Fata when these regions were facing their worst troubles. It is best described in the words of Shina poet Jan Ali who says: Speak not loud, beware the time; it spies on you.

That evening at the Gilgit restaurant, another poet stood up as the Iftar came to an end. He did not recite a verse of his own. Instead, he chose to read Faiz Ahmad Faiz: We shall witness/ Certainly we, too, shall witness/ That day that has been promised/ When these high mountains of tyranny and oppression/ Turn to fluff and evaporate.

Even when people’s pursuit of education both in Gilgit-Baltistan and Chitral borders on the religious, the society itself remains beholden to its traditions. According to Farman Ali, in districts where both men and women are going to universities in large numbers, social attitudes are as backward as they are in any other conservative part of the country. “Men do not look kindly upon women [being] in public view,” he says. “We are liberal in terms of education but as rigid as the people in Diamer when it comes to patriarchal attitudes.”

Chitral is even more split between tradition and modernity since it is also influenced by Pashtun mores of Khyber Pakhtunkwa of which it is a part. It has seen migration from Mohmand and Bajaur tribal agencies in recent years that has brought with it rigid sociocultural attitudes, especially towards women.

In a society that embraces material modernity and its requisites like education but shuns the intellectual progress and individualism they bring, a cognitive dissonance is only a logical outcome. Dad puts it evocatively when he says, “we release minds but we don’t celebrate them”.

The local community’s ambivalence towards modernity, he says, “has created a schizophrenic, paranoid culture that does not allow the individual to emerge even when exposed to international standards of education and knowledge technologies”. The individual, in his point of view, “is fighting a lonely fight” in the presence of a communication rupture between the younger and older generations “that has resulted in the breakdown of traditional social contract”.

In his interaction with the youth, says Dad, he has observed existential angst and anger towards elders who try to control them.

A broken social contract has created new fault lines in communities that were once arranged along caste lines — the Shin are spiritually pure rulers, the Yashkin are landowners, the Kamin are lowly artisans and the Dom minstrels. Ambitious young people now want jobs not meant for their caste group. They aspire to marriages in castes above them. When denied by elders beholden to tradition, they find themselves thwarted.

When, for instance, a young person falls in love with someone from another community, neither religion nor society approve of it. “If the boy commits suicide, the girl follows or vice versa,” says Faizi, the college principal in Chitral.

The communities are now also divided along material lines, between haves and have-nots. Whereas needs of the poor were taken care of in the traditional system – for instance, Nasalo fed the less privileged also – the poor now find themselves without a support system that could feed, dress and shelter them.

When the people of Gilgit-Baltistan or Chitral speak of challenges emerging from modernity and development, they could just as well be speaking of a state hanging on to a status quo that is untenable in the face of change. When Dad mentions empathy and Jahan stresses the need for love, they could be talking about the state – a guardian to the people – having gone callous.

“The government is the mother but its milk does not trickle down here,” says Jahan.

The Sunni residents of Diamer could not be more different from Gilgit-Baltistan’s dominant Shia population. The district is home to banned sectarian outfits that the Balawaristan National Front claims were settled in the region by the state – first for Afghan jihad under General Ziaul Haq when Gilgit-Baltistan first saw sectarian violence that resulted in the killing of 400 Shias; and later under Musharraf when Gilgit-Baltistan, like Fata, became home to militant outfits that locals claim were engaged in militancy in both Afghanistan and Kashmir.

Sectarian violence rose again in 2012 when more than 60 Shia travellers were killed by militants near Chilas, the headquarters of Diamer district. Shia groups retaliated with violence in Gilgit town and suburbs, raising the spectre of the 1980s.

In recent weeks, many girl schools have been burnt down in Diamer where female literacy rate is as low as two per cent. The district’s male literacy rate, at 40 per cent, is also the lowest in Gilgit-Baltistan.

This could be due to a dialectical relationship between sectarian identities and social and economic changes. When one sect adopts a modern outlook, the other, as a reaction, shuns it as an attribute of the ‘other’. In Gilgit, says a Sunni resident, banned militant outfits exhort local Sunnis against sending their children to schools run by Aga Khan-led organisations. “As a result, if there are 420 students in a school, only 20 of them would be Sunnis.”

The Ismaili community also focuses on inculcating a collective spirit and voluntarism among the young. “They train their children to be boy scouts with a community spirit while we train our children to spew hatred. This could only lead to a society that breeds suicides,” he says.

Ironically, the ideas of collective good and selfless service to the community clash with the very notions of individualism and competition that come hand in hand with modern education and development. Young Ismailis, as result, find themselves torn within.

Mir Waz, a Ghizer-based social worker, points to another associated effect of the voluntary spirit that drives its strength from the notion that the world is as good or bad as one turns it to be with one’s efforts or lack thereof. “When [Ismaili children] grow up, they realise that the world is far from being good; they find it rather hostile,” he says.

Angst, thus, takes root among them.

They, though, direct it towards themselves rather than at the society because those imbued with a strong sense of community cannot bring themselves to commit murder. “That would be a crime against society for a child brought up with loving care for the world,” says Waz.

Then there is the state.

At the Iftar in Gilgit, a Sunni student leader from Diamer speaks of the “top-down alienation” of the youth in Gilgit-Baltistan. “Ismailis work hard and get educated but the system does not want them to excel. They doggedly pursue role models like Bill Gates but eventually it is the system that crushes them. It does not allow them to become Bill Gates,” he says.

In Dad’s words, education brings awareness and consciousness about political and fundamental rights and when these rights are suppressed, anger seethes within the young. “Right now the anger is internalised, manifesting itself in suicide. If externalised, it could lead to homicidal behaviour,” he warns.

As exogenous causes for suicide, all these arguments makes sense. Together with other endogenous conditions, these lead to stress and mental health issues – ignored not just in Gilgit-Baltistan and Chitral but also in the rest of Pakistan – such as depression which can lead to suicide.

“Problems related to academics, religion, identity, domestic issues, etc, result in uncertainty about how to deal with life,” says Dr Sadiq Hussain, who heads the department of behavioural sciences at the Karakoram International University. “This is where suicide comes in as a pathological mechanism to cope with troubles of everyday life.”

Why people in Gilgit-Baltistan are increasingly choosing this “pathological coping mechanism”, he says, is because the social environment is vitiated by pressures from multiple quarters.

When several suicides happened in Ghizer in May last year, the government in Gilgit-Baltistan was compelled to take notice. Rani Atika, a woman representative in the region’s assembly, moved a resolution and a committee was formed, with Naji as one of its members. Workshops and group discussions were held; seminars were organised; academics and experts were invited to present their theses and highlight reasons for the surge in suicide cases. Recommendations were made to tackle the crisis.

Dr Mohammad Iqbal, minister for law back when the committee was established, speaks of the measures to “motivate youth towards life” through awareness campaigns involving district administration, religious institutions, civil society and academia. These have not been regularly held though, he concedes.

In the long term, the government plans to set up a psychiatry hospital, induct psychiatrists and psychologists in the local healthcare system, build a shelter for women, create economic opportunities and nurture conditions for employment and empowerment of women.

Rani is not happy with the way the government is handling the problem. “The recommendations I gave have not been implemented or have been implemented half-heartedly. Suicide is a social issue and we need to work with society and its institutions like media, NGOs and communities to create awareness about it,” she says.

One good thing that came out of the recommendations is that Gilgit-Baltistan Chief Minister Hafeezur Rehman has announced that an autopsy would be mandatory in every suicide case to establish that it was not a murder.

This directive will take some time before it is implemented in both letter and spirit.

“The police, being a part of the community, hush up cases before they reach the court,” says Mumtaz Ahmad, a district and sessions judge in Hunza. “The family, the community and the police kill cases at the level of local investigation. We only come to know about them through local newspapers or social media,” he says, making an extremely troubling claim that only two per cent of the reported deaths are suicides; the rest are all murders.

From Chitral to Ghizer and Hunza, this collusion of the criminal investigation system with the community obfuscates an understanding of suicides. It also lets murderers get away with impunity, taking advantage of the “blanket of suicide”, as Ahmad puts it.

Sometimes there is no news for days and weeks of girls who fling themselves into the rivers. For their families, they just go missing. The boys do not go missing because they opt for rope or a gun to kill themselves.

As the river flows through valleys and villages, someone downstream will find the body of the drowned girl sooner or later. They pull her out, wrap her in cloth and go around asking if a woman or a girl from someone’s family has gone missing. It is done quietly, no-questions-asked. The finders know it happens all the time and it can happen to them as well. Just as they would not want it brought out in the open, so do others. Once a dead body reaches its home, it is buried quietly, without informing the police, without an autopsy.

From Yasin in Ghizer to Hunjgool in Chitral and Gojal in Hunza, the villagers live by this law of silence because they are of the same culture, the same stock, tied in ethnic and blood bonds. The geography favours this silence. Distances are big, villages remote. The police often do not get to know about a death before the dead person is already buried.

Yet, one often hears in conversations with local social activists that suicides could be masks for murders. Israr, from HRCP, for instance, points out that a suicide is not always the reason for the sudden and unnatural death of a woman. “Of the total suicide cases reported in Ghizer, 10 to 15 per cent are honour killings,” he claims.

Drug trade and inter-agency rivalry are two other factors that lead to killings that are then concealed as suicides.

Both Chitral and Gilgit-Baltistan are located on major drug routes due to their proximity to China, Afghanistan, Central Asia and India. With little prospects of employment for youth, some of them easily fall prey to drug traffickers. “The youth take drug consignments and are killed when caught or when deals go wrong. Their families show these as suicides,” says Farman Ali.

Rival intelligence agencies of India and Pakistan, according to him, are also active in Gilgit-Baltistan. “They employ youth as informers and eliminate them when not needed anymore.” These, too, are later portrayed as suicides.

Durdana Sher, a Ghizer-based reporter, who is lauded for frequently reporting on the issue, also believes many cases are murders covered as suicides. “Ask the police how many postmortem reports have been prepared, how many cases identified for what they are – murder or suicide – and how many killers punished,” he says.

People also widely believe that the reported cases of suicide – or honour killing or murder – are just the tip of the iceberg, made visible by an active media in, say, Ghizer. This is not the case in Hunza where the media is not so active. So, there is a lot that goes unreported.

Local media, in fact, is under pressure from local communities not to report in many places. That is the sense one gets while talking to local journalists who seem to share with their community the perception that reporting suicides brings disgrace to Gilgit-Baltistan. Others who have reported doggedly on the issue now feel defeated. “I have been reporting on suicides since 1995. Now I am blamed for bringing a bad name to the district,” says Durdana Sher.

He also points out that local authorities lack the expertise, tools and resources to investigate reported suicides properly. Doctors at the district hospital in Ghizer examine the dead but they have to send out the viscera to forensic facilities in Lahore and Peshawar for a detailed report.

A single postmortem costs about 50,000 rupees which the police usually do not have, says Durdana Sher. “The police do not even have proper containers to send the viscera for postmortem.”

And so bodies are emptied out in plastic bags. They are sent out over long distances without proper cooling. They go bad; they are perhaps examined, perhaps reported on, perhaps thrown into the incinerator or a garbage dump.

“Postmortem reports do not come in for as long as a year by which time the case is dead given local attitudes to suicide,” he says.

“In the absence of a report, who can establish what the cause of death was.”

This article was published in the Herald's September 2018 issue. To read more subscribe to the Herald in print.