70 years, 70 questions

Editorial

Pakistan attained the age of 70 on August 14, 2017. The occasion warranted serious introspection by us, Pakistanis, about the course of our history and the present (and future) direction we have taken as a state and society. There are multiple ways to do that introspection but none closer to the reality on the ground than an exercise that elicits and puts out the views and world views of men and women who – coming as they do from different parts of the country and working in different fields – are themselves parts of that reality on the ground.

That is the idea behind this public opinion survey.

It aims to find out the public’s views on social, cultural, economic, global/diplomatic, strategic, religious and political issues (among others) that form their opinions and inform their everyday lives. A few main objectives of this exercise were as follows:

To create a verifiable set of primary data about public opinion on the issues that divide, unite, drive and defeat Pakistanis in different parts of the country and in different fields of life. The findings will serve as a basis for in-depth analyses of various historical trends in the Pakistani state and society (these analyses have been published alongside the survey’s findings);

To collect and collate public opinion on issues of public importance so that academics and researchers, both inside Pakistan and outside the country, can employ the survey in their work;

To offer insight into the thinking of a representative cross section of Pakistan’s people to non-governmental organisations, advocacy groups, international non-governmental entities, think tanks and the media so that they can assess and recalibrate (if and where required) their own work in the light of the survey’s findings;

To provide government departments, political parties and bilateral and multilateral donors a snapshot of the ideas and ideologies prevalent in the Pakistani society in order for them to assess and understand the impact and/or consequences of their policies over the last 70 years; To assess the progression of public opinions, world views, biases, prejudices, predilections, likes and dislikes that have prevailed in the Pakistani society over the last seven decades.

Like all surveys, this one has created and followed a demograhic sample to attain its objectives. This sample is based on various demograhic parameters relevant to the reality of life in Pakistan and, in essence, is a manufactured universe where a whole country of 210 million people has been reduced to a much smaller set of numbers so that Pakistanis, thus identified, could be reached and their opinions recorded.

But this whole exercise of putting together a meticulously designed sample would have come to naught if the British Council in Pakistan had not agreed to back the project with its financial commitment. From that stage onwards, its representatives ensured that nothing went wrong with the survey’s technical and editorial aspects and everything ran smoothly as far as expenses on the project were concerned.

Like any other human endeavour, surveys – especially of such an expansive scope – are susceptible to errors. From the brains that conceive the idea of a large-scale exploration to the hands that print them eventually, a lot of stages, individuals and technologies constitute the process, each of which are prone to making mistakes. A credible survey is not a perfect one, but one that acknowledges this fallibility of the method and seeks to minimise it accordingly — something this Herald-British Council survey has attempted to embody.

In this regard, it is worth mentioning the concept of margin of error. Since no matter how large the sample size, it could never truly include the entire population; margin of error is an indicator of the effectiveness of a survey in truly representing the population’s opinion on the questions asked. Based on the confidence level the body conducting the survey expresses, the margin of error depicts the extent to which the results of the survey could be trusted.

For this survey, at 99 per cent confidence interval for the population of Pakistan – 210 million – the selected sample of 7,000 respondents has a margin of error of 2. This means that for any given question on the survey, the response ranges from 2 points above to 2 points below the actual results of the value. In this survey, to illustrate, 60 per cent of the respondents feeling highly satisfied with a government body should be seen as 58 to 62 per cent of the total population feeling highly satisfied with a government body.

The survey methodology, like any other research methods, is and should be premised on the consent of the respondents to withhold their opinions about any question. They may feel uncomfortable, unqualified or merely uninterested in expressing their opinion. The response rate for the overall survey, that is the percentage of the respondents who answered the questions, is 96 per cent, which means four per cent of the respondents chose not to answer the questions. It is worth noting the lowest response rate amongst the 10 sections of the survey is observed in politics (95.1 per cent), law and justice (92.71 per cent), and media (94.26 per cent) — otherwise hotly debated arenas of national discourse.

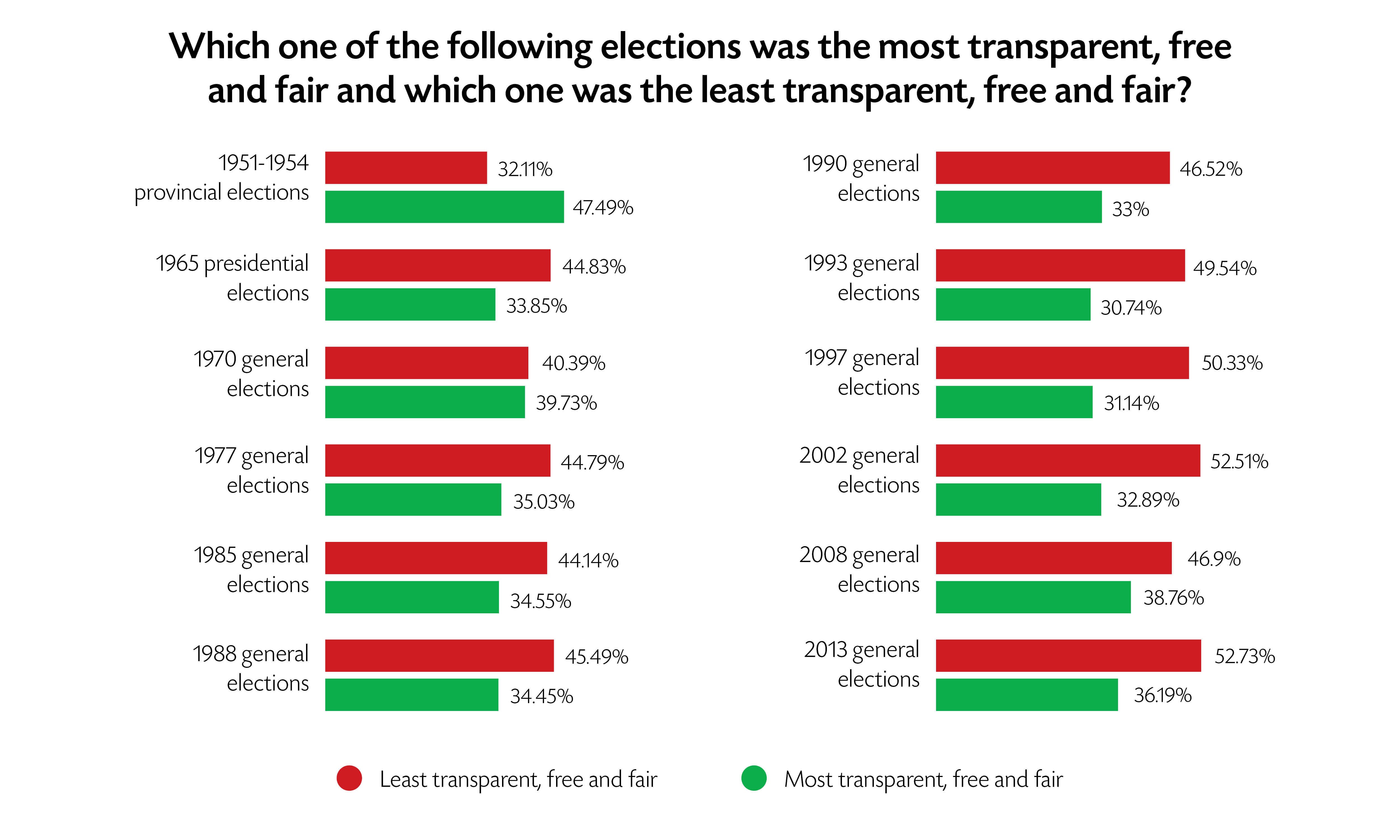

In the section of politics, the question that was least answered (18.4 per cent respondents chose to not answer this question) asked respondents to choose an election from the nation’s history they found to be the most and least transparent, free and fair. In the section of law and justice, the question that a staggering 26 per cent of the respondents did not answer (by far the most unanswered question in the entire survey of over 700 questions) asked them to narrate their experience with different kinds of courts in Pakistan — military, civil, jirgas amongst others. This is highly telling of the accessibility of our judicial system to the masses.

Finally, in the section of media, the question with the lowest response rate (21 per cent) asked the respondents what they thought about the state of the media in different political regimes. Given the current increase in the surveillance of electronic, print and social media by the state and policing of dissent in various arenas of social life, it is plausible to presume many of our respondents felt uncomfortable voicing their opinion on the subject.

The fact that there has been little done to collect and organise data on the social and political life of Pakistan would go largely uncontested, save for a few commendable efforts in the last decade. Surveys such as this one are an antidote to this dearth of information because not only do they reveal the general temperament of the society but also the continuities and changes within it based on chosen parameters. The subjective experiences of those living by the ocean differ vastly from those dwelling in the mountains and the survey has attempted to record the voices of both these ends and of those in between.

Out of 7,052 respondents, 3,946 were from Punjab, forming 55.96 per cent of the total; 1,643 respondents from Sindh making up 23.29 per cent of the total sample; 904 respondents from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (12.82 per cent); 362 respondents from Balochistan (5.13 per cent); 146 respondents from the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (Fata) – 2.07 per cent – and 51 respondents from Islamabad, forming 0.72 per cent of the total sample.

We also ensured that the survey represented both the urban and the rural populations in every province. In Punjab, for example, 65.21 per cent of our respondents were from rural areas whereas the remaining 34.79 per cent were from the urban centres. Similarly, in Sindh, 45.71 per cent of our respondents were from rural areas and 54.53 per cent from urban. In Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, 77.99 per cent of our respondents were from the rural areas whereas 22.01 per cent were from urban centres; in Balochistan, 71.27 per cent were rural and 28.73 per cent urban; in Fata, 95.89 per cent of the respondents were from rural areas and 4.11 per cent from urban; in Islamabad, 37.26 per cent of the respondents were from rural areas and 62.75 per cent from urban areas.

In addition, the survey intended to represent the opinions of both men and women in each province. In Punjab, for example, men constituted almost 52 per cent and women 48 per cent of the total pool of respondents; around 53 per cent male and 47 per cent female respondents in Sindh and Balochistan; 51 per cent male and 49 per cent female respondents in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa; 54 per cent male and 46 per cent female respondents in Islamabad and Fata.

We also ensured that our respondents spoke various languages. Approximately nine per cent of respondents spoke Urdu, 44 per cent spoke Punjabi, 13 per cent spoke Sindhi, 15 per cent spoke Pashto, 11 per cent spoke Seraiki, three per cent spoke Balochi, and four per cent spoke various other languages.

Disclaimer:

The interpretations offered in this special issue are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the British Council and the Herald, their employees or those individuals who contributed to the research.

The snapshot of a nation

What do Pakistanis think about themselves at 70?

By Ayesha Azhar Shah

Each decade – in fact, each year – demands introspection. At 70 years, Pakistan is certainly no longer basking in the glow of youth. As citizens’ relationship with the state has evolved over the last seven decades, the country, indeed, is coming to recognise the contours of its national character. Undoubtedly, the history of this state-citizen relationship is replete with weaknesses and disappointments as well as successes and achievements.

People across the country now possess sufficient historical perspective to understand and analyse this relationship — some armed with knowledge of history and others equipped with perceptions based on personal and/or inherited experience. But as they look back at their past and compare it with the present, they find themselves in a bit of a tangle between optimism and pessimism.

Where they are not confused, though, is their support for democracy. The have always welcomed the return of democracy – overshadowed by three decades of military rule – with a spring of hope and with the greatest of expectations. This is not to say that they have also tolerated floundering democratic governments with patience and equanimity: they have always been increasingly impatient with democratic regimes that fell short of their promise.

The respondents for this British Council-sponsored survey constitute a sample of 7,000 Pakistanis who represent various provinces, genders and ethnicities (as determined by their mother languages). They also have representation from across various educational, occupational and age groups to make the sample representative of today’s Pakistan.

In its scope and depth, the survey demanded a deep reflection on the part of these respondents on the impact and result, both preemptive and reactive, of the state’s policies and the society’s evolution in various eras and across a wide range of sociocultural, political and economic issues and sectors. They were asked 70 detailed questions about a wide range of subjects — economy, politics, strategic affairs, foreign relations, religion, governance and administration, human rights, law and justice, arts and culture, and media.

The fieldwork for the survey began in July 2017 with a deadline of one month, but the rigidity of the sample and the breadth of the questions meant that it required a lot more time and effort to collect genuine responses than we could have initially anticipated. The process of conducting the survey also ran into several other unforeseen roadblocks: some surveyors backed out at the last moment; others promised but failed to deliver. Yet another group of surveyors failed to follow the sample, necessitating the deployment of new surveyors. The whole process was finally concluded in November 2017.

The results paint a picture of an optimistic nation. While people acknowledge and continue to grapple with issues associated with being citizens of a young third-world nation state, they feel they are on a slow but steady upward path to a better life. More than 55 per cent of the respondents feel their lives have improved in economic terms, with an even greater number of people expressing satisfaction in this regard in rural areas than in urban ones. Predictably, such numbers are higher for Punjab than for the other provinces.

Interestingly, though, the respondents seem to have disregarded historical evidence and ranked the economic performance of democratic governments higher than that of military governments. This clearly highlights that public perceptions do not necessarily corroborate or follow factual positions and that people’s views are, rather, informed and influenced unevenly by a multitude of events and factors. This also explains why these views often appear confused and contradictory.

The survey suggests that Pakistan has made some progress with reference to human rights as well, especially in terms of awareness about and respect for women’s rights. Almost 60 per cent of the respondents feel there has been an improvement in women’s rights over the last seven decades, with more than 42 per cent saying that people are generally better educated in this regard than they have been in the past. This, however, is where the optimism ends. A large number of respondents note that the human rights situation for marginalised groups, other than women and children, has worsened.

The respondents see national security as the biggest hurdle in the protection of human rights. They also see strong links between security concerns and economic development, with 79 per cent surmising that security problems have either influenced (30 per cent) or strongly influenced (49 per cent) Pakistan’s economy.

The security situation is similarly seen as having impacted the economy more than it has impacted the political or social fabric of the society. A strong causal relationship between national security and such indicators as centre-province relations, democratic evolution and even the provision of civic amenities, too, has been suggested by the survey.

The responses also exhibit a strong faith in hard power to secure the country. Reinforcing popular conceptions, many people feel that, more than any endeavour, the acquisition of nuclear weapons has helped secure Pakistan the most. An overwhelming 78 per cent of them feel nuclear arms have contributed more to the country’s security than anything else. Effective diplomacy and support from foreign allies is perceived to be decidedly less important than military force.

When it comes to foreign allies, a large number of respondents rather predictably note China as a positive factor in Pakistan’s security. An almost equal number of those surveyed feel that India and the West are negative influences on national security. This, too, is not a surprising result. The official optimism over the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) appears to have spilled over into public perception as well, with 43 per cent marking this initiative as Pakistan’s most significant foreign policy development. What is striking is that the incumbent government, which claims credit for making CPEC possible, has been given a low ranking when it comes to the handling of foreign policy.

Overall, more than for any other period in the last 70 years and despite the difficulties of the country’s initial years, the respondents feel that Pakistan was doing the best in most fields in the half decade or so immediately after its birth. More than 46 per cent of them say Pakistan was most secure under the leadership of Muhammad Ali Jinnah and Liaquat Ali Khan, significantly more than at any other time. This trend can also be seen in other areas, with more than 43 per cent respondents saying that human rights were upheld most effectively during that early period.

The justice system is also thought to have been most effective during that period. Same goes for corruption: Pakistan is perceived to have been the least corrupt under the Jinnah-Liaquat regime. Early losses also appear to grip the popular imagination. Most of the respondents see Jinnah’s early death as the most significant political incident, followed by the separation of East Pakistan.

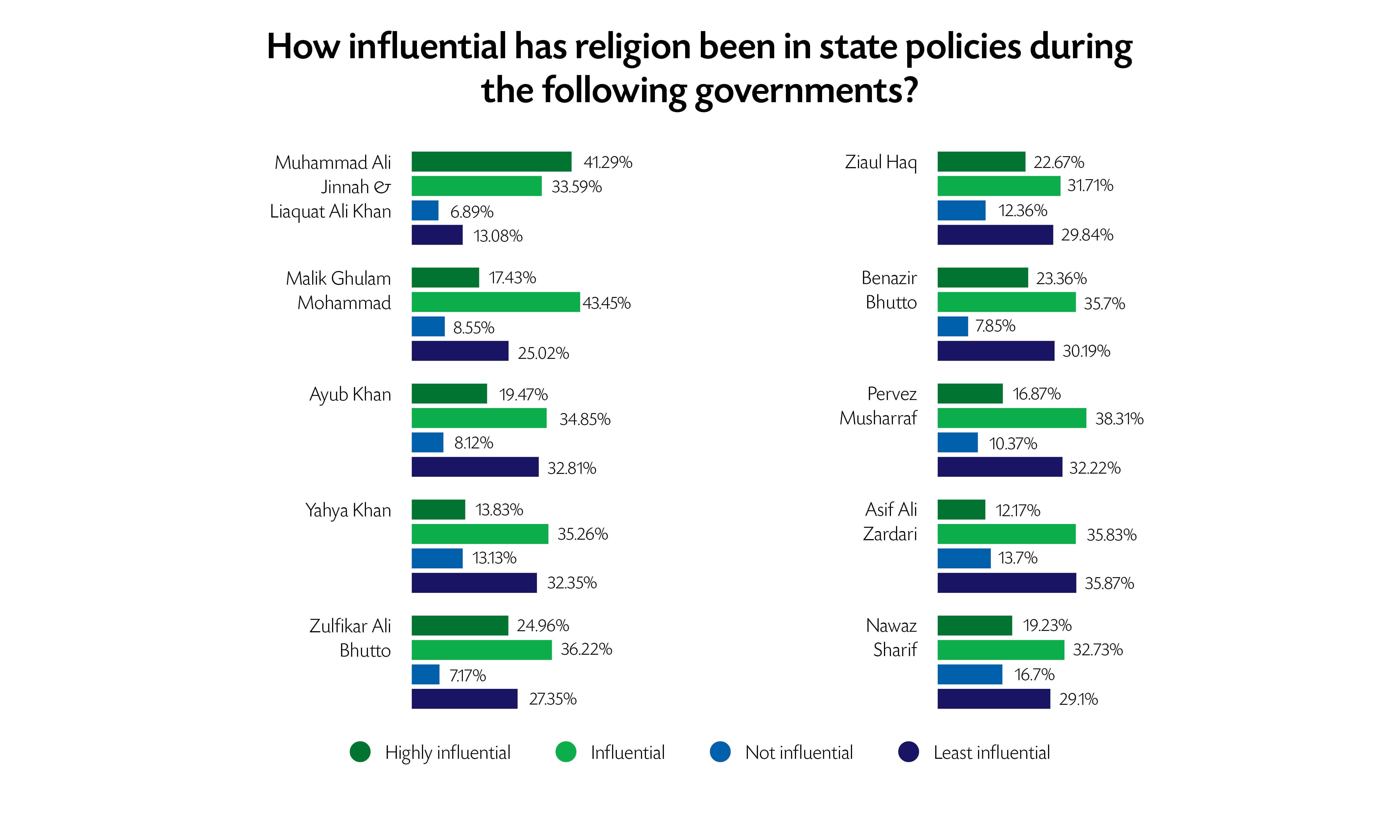

The irreconcilable religious narratives surrounding Partition, too, continue to make their presence felt through public perceptions regarding the importance of religion in the national life. Almost 60 per cent respondents point to the overwhelming impact of religion on the country, especially its significant impact on education. A similar number of respondents feel that Pakistanis are intolerant towards those who belong to a sect other than their own. Surprisingly, however, fewer respondents feel that Pakistanis have the same level of intolerance towards people who do not share their religion.

The convergence and divergence of perceptions from historical facts hints at people’s biases and ideological bents, at times revealing the influence of popular narratives and, at other moments, offering discerning insights. There is an obvious tendency among the respondents to view the past, especially the early years of the country’s life, through the rose-coloured lens of nostalgia, using the yearning for what could have been to comment on the malaises of the present.

The outcomes of the survey are, at times, predictable and at other times conflicting with preconceived notions. If nothing else, this alone warrants a deeper analysis of its findings across the range of subjects it covers.

This special publication offers at least some preliminary analysis on each of the 10 sections of the survey. It aims at offering a snapshot of the public’s perceptions at this point in time in various fields of national life.

To construct as precise a sample as can be possible, we initially planned to stratify it along eight different variables. The first stratum was province/region and the total population was divided into six regions — Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Punjab, Balochistan, Sindh, the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (Fata) and Islamabad. The regional population was then divided into urban and rural locations as well as on the basis of gender and mother languages. To get a better distribution of the sample across the whole society, educational, age and occupational groups were included as additional variables.

Two main data sources were used to devise the sample: the 1998 census (for the break-up of population on the basis of regions, divisions, districts, urban/rural locations, gender and mother languages); the Labour Force Survey (LFS) 2014-15 (for age, education and occupation groups). The LFS was used because it was a relatively more current and reliable source of demographic statistics than any other set of data available at the time of the survey’s fieldwork. Major findings of the national census of 2017 became available many weeks after this survey had already begun.

The survey questionnaire – carrying seven questions for each of its 10 sections – was finalised after multiple revisions and was designed to elicit a comprehensive range of responses. Each question was framed in a way that allowed the respondents to provide well-thought-out and nuanced answers. For example, one of the questions asking the respondents to rate the performance of Pakistan’s economy under 10 different governments was supplemented with additional questions further probing the answers.

The questions were also carefully constructed so as not to let any bias get into their wording. For example, instead of asking, “Has Pakistan’s foreign policy been influenced by the United States?” we asked, “How has Pakistan’s foreign policy been influenced by the following? a) United States, b) Saudi Arabia, c) China, d) India,” etc. The options provided to answer the question were also not presented as cut and dried. These included: a) Insignificantly, b) Neither significantly nor insignificantly, c) Significantly, or d) Very significantly, in order to discern the various shades and nuances of public opinion.

The ‘I don’t know’ option was not included in the survey in order to make each respondent reflect on his/her perceptions and then offer a meaningful response.

The questionnaire was translated into the Urdu, Punjabi, Balochi, Seraiki, Sindhi and Pashto languages before it was sent out into the field. A dry run of the survey was conducted for a week in July 2017 and some questions were modified based on the feedback from it. The revised questionnaire took anywhere from 40 minutes to two hours to complete — a massive improvement on the earlier one that took more than two hours for completion every time it was put to a respondent.

The survey was conducted in 70 districts across Pakistan via an online app to ensure error-free data entry and for the results to be verified and collated instantly. Surveyors were sent a detailed sample on a spreadsheet to allow them to match each respondent with a sample number to ensure compliance. Each of the surveyors was given a particular number of respondents to survey – not exceeding 150 – along with detailed instructions on how to use the app and how to conduct the survey.

Initial challenges included finding credible surveyors in each of the districts constituting the sample and, given the precision of the sample, finding matching respondents. Eventually, age, education and occupation parameters had to be randomised because of widespread discrepancies between the latest available data and the situation on the ground.

In some areas – especially in Kurram Agency of Fata, and Swabi and Bannu districts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa – female respondents who met the demographic sample would only agree to be surveyed by female surveyors due to purdah concerns. Finding suitable female surveyors in rural areas proved difficult at times.

Many of the survey questions were admittedly challenging for uneducated respondents with whom even the names of past prime ministers and presidents failed to resonate. For example, some of the respondents, especially in the rural areas of Balochistan, found questions requiring comments on civic amenities and legal structures irrelevant to their reality. Similarly, respondents in Fata found questions on elections to be irrelevant. In some areas, the surveyors were viewed with suspicion. In other places, people were reluctant to participate in the survey due to time constraints and also due to the fear of making their views public.

Security concerns also arose in some places. In at least one place, district Khuzdar in Balochistan, security agencies questioned the surveyors about the intent of the project.

There were some technological challenges as well. Given that the survey was meant to be filled digitally, it was necessary for each surveyor to possess a smartphone or a tablet. This proved to be a problem in some areas in southern Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Furthermore, filling survey forms online to ensure their instant transfer to the data hub was not always seamless due to bad internet speed and/or the lack of internet connectivity at many places across Pakistan. Some of the forms filled by surveyors, therefore, could not be located at later stages, necessitating repeat surveys.

Data verification was carried out simultaneously with data collection, in order to minimise errors during fieldwork. Incoming responses were monitored by a team of coordinators at the Herald as they came in. A number of randomly chosen respondents were also contacted via phone for further verification.

Overall, compensating for erroneous entries, technical glitches and the violation of survey parameters meant that more than 8,000 responses had to be collected during fieldwork. Excess entries were later discarded after a thorough process of data verification and the correspondence of entries to sample parameters.

Due to zero tolerance for deviations in the main stratifications for the sample and multiple verifications, it is safe to assume that the results of the survey provide an accurate reflection of the public’s perception of Pakistan’s history. At first glance, the contradictary sentiments that emerge may surprise, but they provide evidence of the multilayered and complex disposition of Pakistani society. Expecting a rational and linear narrative from a survey of perceptions would mean disregarding the varied experiences of Pakistanis.

A glance at some of the results, indeed, poses more questions than answers: Why is it that the death of Muhammad Ali Jinnah left the strongest mark on Pakistan’s history? Was it our biggest loss? What was the golden era of the country in various fields? These and many more questions necessitate further probes into the whys and why-nots of our history so that we can arrive at a deeper understanding of today’s Pakistan.

As the country enters its eighth decade, with a fresh census just conducted and a new election round the corner, we at the Herald hope that this survey will shed some serious light on the historical consciousness of the nation. The information it offers about the past and the present may, in turn, help Pakistanis move forward towards a better future.

The writer was lead coordinator and editorial consultant for this survey. She works as a business development executive at the Centre for Excellence in Journalism at the Institute of Business Administration, Karachi.

Human rights

Rights and wrongs: How the public looks at the state’s human rights track record

By I A Rehman

Although Pakistan came into being 18 months before the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) was adopted, the Pakistan movement had reached maturity at a time when human rights already entered the political discourse in all parts of the world. Furthermore, protection of the rights of non-Muslims in Pakistan was duly accepted in the Lahore Resolution of 1940 itself.

Thus, we find that the first step Muhammad Ali Jinnah took towards framing a constitution for the new state was forming a committee under his own presidentship to draw up proposals on human rights and the rights of minorities. This committee completed a large part of its work in 1948; though the fundamental rights chapter of the constitution, which incorporated nearly all articles of the UDHR, was adopted in October 1950 — about a year before Liaquat Ali Khan’s assassination.

This may partially explain why more than three-fourths of Pakistanis interviewed for this survey believe that the government headed by Muhammad Ali Jinnah and Liaquat Ali Khan upheld human rights more effectively than the succeeding leaders. The respondents also display a pro-democractic inclination and reveal that the national security syndrome is the biggest impediment to (the enforcement of) human rights.

According to some other findings of the survey, the condition of all vulnerable groups, except women and children, has declined on the human rights scale. A sizeable section of the population believes their awareness of human rights has declined and that they are in a worse position than their parents and grandparents’ generations.

Before analysing the survey responses related to human rights, however, it may be appropriate to recall some developments during Pakistan’s early years.

Human rights, in the form of labour rights and fundamental rights of citizens in a democratic state, had entered the political discourse in the India-Pakistan subcontinent in the 1920s, if not earlier — that is, at least two decades before independence. Although a British colony, India enjoyed membership of the League of Nations and quite a few of the International Labour Organization (ILO) conventions adopted by the League, which were ratified by the government of India in the 1920s.

A committee of politicians who were demanding freedom from colonial power – formed under the chairmanship of a Congress leader, Motilal Nehru – released a draft constitution for a free India in 1928. Known as the Nehru Report, this document included a chapter on fundamental rights, such as the right to life and liberty, freedom of belief, freedom of expression and freedom of association, etc. Muslims under the leadership of Jinnah rejected the report on the grounds that it did not accept their demand for their separate representation in Parliament, and for that reason they generally ignored the part about basic rights as well.

Thus, discussions on human rights had been continuing for several years before Pakistan was created and the new country’s leaders were aware of them. But the knowledge about pre-independence references to fundamental rights and the work on the subject in Pakistan between August 1947 and March 1956 – when the first indigenous constitution came into force – were limited to a small number of people. Few Pakistani citizens today might be able to recall how the early governments upheld human rights. This lack of knowledge could be the reason why they tend to view the human rights situation back then in a favourable light.

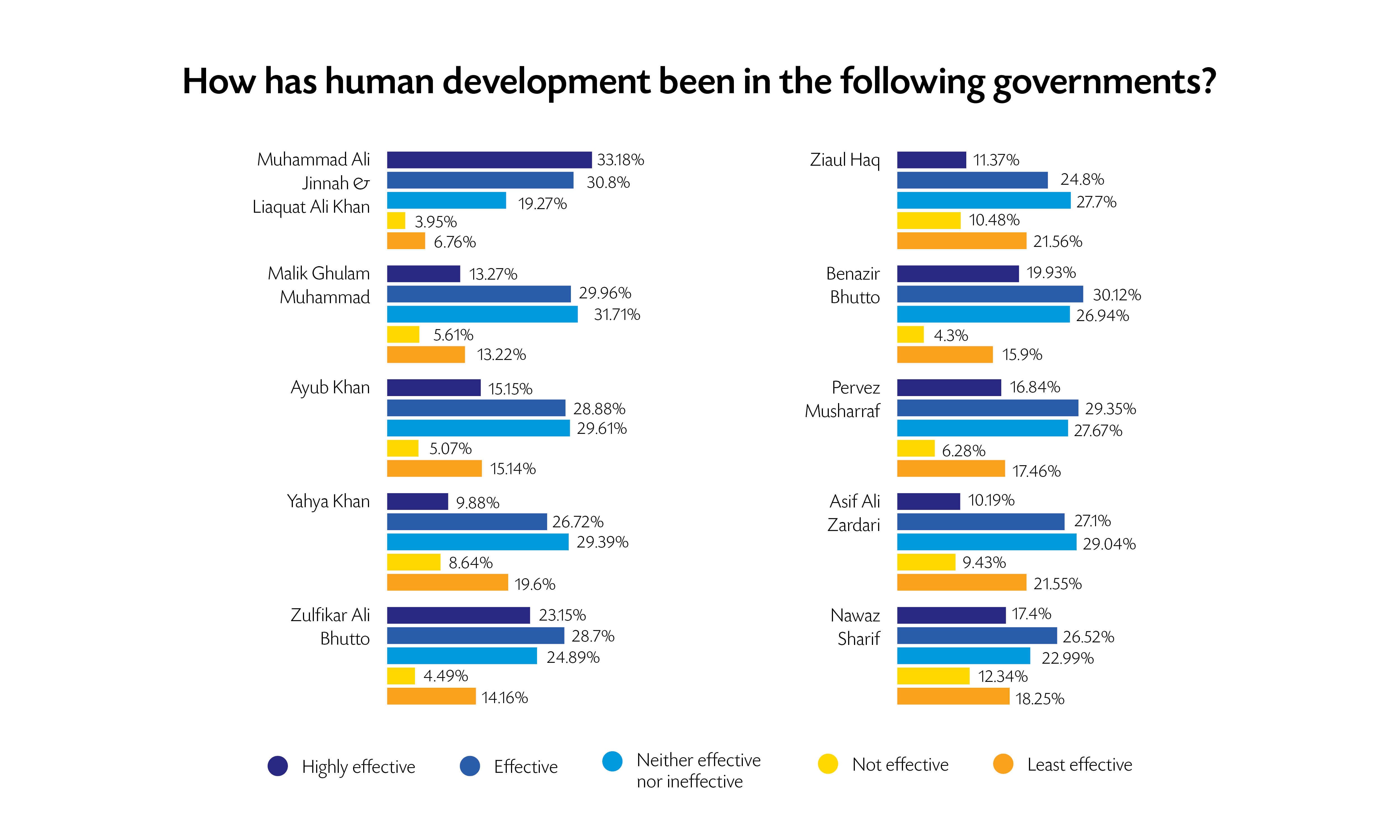

The question the survey asks about human rights under governments headed by different leaders – from Muhammad Ali Jinnah/Liaquat Ali Khan to Nawaz Sharif – is as to how effectively they have upheld human rights. If we take the respondents who said ‘most effectively’ and ‘effectively’ together, we can get the relevant government’s approval rating and if we put together all other responses – ‘least effectively’, ‘not effectively’ and ‘no answer’ – as adverse remarks, we get the following picture:

More than three-fourths of the respondents (76-77 per cent) believe that the Muhammad Ali Jinnah/Liaquat Ali Khan government (1947-51) upheld human rights to a great extent. This view could have been based upon Jinnah’s speech of August 11, 1947, the work of the committee on fundamental rights, the adoption of these rights by the Constituent Assembly in 1950 and the grant of right to vote to all 21-year-old men and women in Punjab and the NWFP (now renamed as Khyber Pakhtunhkhwa) in 1951. The adverse responses could perhaps be attributed to the revival of preventive detention/security laws and attacks on freedom of expression, which resulted in the banning of newspapers.

The government’s approval rating fell from 76.77 per cent to 59.68 per cent and opposing opinion rose from 17.6 per cent to 34.33 per cent during Ghulam Mohammad’s reign — the biggest factor perhaps being the sacking of the Nazimuddin ministry and the dissolution of the Constituent Assembly.

Approval rating for the human rights situation fell further under the military rules of Ayub Khan and Yahya Khan to 55.38 per cent and 48.21 per cent, respectively, while adverse responses rose to 39.73 per cent and 46.18 per cent, respectively.

Under Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, approval rating picked up to 62.02 per cent and the adverse opinion fell to 33.6 per cent.

The trend was reversed with General Ziaul Haq as approval rating fell to 47.02 per cent and adverse rating rose to 49.14 per cent.

The trend was reversed again under Benazir Bhutto when approval rating improved to 62.45 per cent and adverse opinion fell to 35 per cent.

According to the survey respondents, the human rights situation deteriorated under Pervez Musharraf and Asif Ali Zardari as their approval rating fell to 55.65 per cent and 48.08 per cent and the adverse opinion rose to 42.17 per cent and 49.58 per cent, respectively.

The situation improved a little under Nawaz Sharif as the approval rating rose to 50.87 per cent and adverse opinion fell to 46.99 per cent.

These findings reveal the respondents’ view that democratic rule has been a decisive factor in a situation favourable for human rights. It is possible they have been translating their pro-democracy bias into a favourable climate for human rights.

The largest group of respondents (21.56 per cent) has held ‘national security’ to be the biggest impediment to (the enforcement of) human rights in Pakistan. The other impediments in a descending order are: culture and custom (14.11 per cent); legal system (13.82 per cent); religion and religious belief (13.55 per cent); administrative system (10.37 per cent); economic system (9.46 per cent); education and curriculum (7.41 per cent); feudal system (6.15 per cent); and tribal system (2.98 per cent). The survey vindicates the citizens’ perceptiveness and the soundness of their judgment.

It also shows that 54.96 per cent of the respondents believe they have more freedom of association than their parents and grandparents had. Only 28.33 per cent of them think they have less freedom of association and 14.75 per cent do not see any change.

With respect to other rights, a majority of the respondents consider themselves worse off than their parents and grandparents. Slightly less than half (49.42 per cent) believe they have a better right to education and 48.18 per cent think they have an improved entitlement to information than their parents and grandparents. In these two categories, the percentage who do not notice any change, stand at 14.18 per cent and 18.65 per cent, respectively.

The present generation is seen by a large number of respondents as being in a worse position compared to their parents and grandparents with regards to the right to speak; only 42.45 per cent believe they are better off than their predecessors. On an average, nearly 16 per cent of the people surveyed see no change in this regard since the days of their grandparents.

This is a stunning indictment of the state in terms of its neglect in some of the key human and social rights of the people.

With regards to the human rights of underprivileged/marginalised persons, the survey reveals a highly disturbing situation. With the exception of women – whose human rights cover has improved according to 59.78 per cent of the respondents, and children, whose access to human rights has improved according to 38.42 per cent of the respondents — conditions for all other groups has deteriorated over the past 70 years.

The opinion is nearly equally divided with regards to religious minorities: while 39.01 per cent of the respondents think the minorities’ enjoyment of human rights has improved, a somewhat larger number – 39.95 per cent – thinks their condition has deteriorated.

The position of labour (industrial, perhaps) has deteriorated perceptibly: only 32.01 per cent of the respondents say their enjoyment of human rights has improved; according to 40.73 per cent, their human rights situation has deteriorated.

The condition of peasants is seen to have degenerated even more than that of workers: only 28.28 per cent of the respondents believe the human rights situation for peasants has improved while 43.42 per cent hold that it has deteriorated. A little higher on the ladder are agricultural workers: 31.81 per cent of the respondents see an improvement in their rights over the last 70 years while 41.54 per cent see a deterioration in them.

The members for ethnic minorities are at the same level as agricultural workers: 31.49 per cent of the respondents say their human rights situation has improved while 36.73 per cent say it has deteriorated.

At the bottom of the ladder lie the transgender citizens. Their human rights situation has improved according to only 28.79 per cent respondents and deteriorated according to 40.48 per cent of them.

The number of respondents who do not see any change in the human rights situation of vulnerable/marginalised sections of the society varies from 16.22 per cent in the case of women to 27.64 per cent in the case of ethnic minorities.

Questions about laws related to women’s rights in selected areas have brought out interesting responses. The happiest response is with regards to a woman’s right to education: a little more than half of the respondents (50.74 per cent) say the laws have become better; only 28.3 per cent say they have become worse. Another 18.87 per cent have seen no change.

With regard to laws about women’s rights to vote, the responses indicate approval of changes in laws: 46.79 per cent of them see an improvement and 28.15 per cent see a deterioration; 21.97 per cent see no change.

As far as women’s right to marry by choice is concerned, 53.3 per cent of the respondents believe laws have improved and 22.67 per cent think they have deteriorated. For 22.21 per cent, no change has taken place.

The opinion is almost evenly divided on the changes in laws related to women’s rights to divorce: for 36.84 per cent, the laws have improved but they have deteriorated for 36.59 per cent. For 24.26 per cent, nothing has changed.

The situation is not bad as far as laws guaranteeing women’s rights to work outside their homes is concerned: 44.08 per cent think improvement has taken place and a smaller number (34.56 per cent) believes laws have deteriorated. For only 19.87 per cent, no change has been noticed.

The situation regarding laws covering women’s rights to inheritance, however, remains quite bad: only 36.79 per cent have noted improvement in laws and 34.23 per cent have seen deterioration; 26.9 per cent have seen no change. This is similar to the situation regarding laws related to women’s rights to family planning: 37 per cent note improvement, 35.09 per cent find deterioration and 25.7 per cent see no change.

Comparitively, the situation with regards to laws concerning women’s rights to choose their attire for appearance in public: improvement is noticed by 38.65 per cent, deterioration by 33.89 per cent and no change is noticed by 27.04 per cent.

In regards to violence against women, more people (35.66 per cent) think the legal changes have been good while 32.55 think otherwise.

The respondents are generally dissatisfied with the impact of changes in laws on the rights of non-Muslims and other vulnerable groups. The most positive legal change, according to 54.28 per cent of the respondents, is with respect to their right to observe their religion freely. Another 23.88 per cent think the changes have made laws worse and 19.82 per cent see no change. The respondents are evenly split on the issue of laws on the protection of non-Muslims’ places of worship; 39.56 per cent say the laws have deteriorated while 38.29 percent have noted improvement.

Changes in freedom for the celebration of non-Muslim cultural events are viewed more favourably: 44.98 per cent of the respondents believe the situation has become better while only 29.67 per cent think otherwise. Opinion is evenly divided on the situation with reference to non-Muslims right to speak: 36.28 per cent think the changes have been good while 36.78 per cent think otherwise.

The respondents are quite clear that changes in laws have not done well for transgender citizens: only 31.92 per cent think changes have favoured this section of the society while 35.45 per cent feel otherwise. Most of the remaining respondents see no change.

As for the changes in laws related to protection of children against child labour, 33.96 per cent notice improvement while 36.05 per cent see deterioration. Similar are the findings with respect to laws on children’s sexual abuse: only 32 per cent of the respondents notice improvement in laws while 35.74 per cent see deterioration.

According to 50.2 per cent of the survey respondents, awareness about human rights in general has improved over the past 70 years. It has deteriorated for 25.4 per cent and 21.67 per cent see no change. However, with respect to awareness about certain specific human rights, the responses are quite mixed.

Improvement has been seen in the awareness about freedom of thought by 40.87 per cent of the respondents and deterioration by 33.05 percent. Those who believe awareness about equality of opportunity has increased (34.97 per cent) are fewer in number than those (39.81 per cent) who think it has deteriorated.

As far as equality before law is concerned, 37.26 per cent report improvement in awareness about it, 34.87 per cent report deterioration and 25.13 per cent see no change. Improvement in awareness about social justice has been noted by 33.32 per cent and deterioration by 38.85 per cent while 25.3 per cent have noticed no change.

Those who have seen improvement in awareness about economic justice (31.78 per cent) are outnumbered by those who have noted deterioration (37.74 per cent); another 27.28 per cent have seen no change. Those who notice improvement in awareness about political justice (30.06 per cent) are likewise outnumbered by those who have seen deterioration (39.21 per cent) and 27.57 per cent have noticed no change.

The writer is a senior journalist, peace activist and human rights advocate. He has served as editor-in-chief of the Pakistan Times and has been a director of the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan since 1990.

Media

Views as news: Why is news media seen as compromising public interest

By Adnan Rehmat

Historically the media space in Pakistan has been tightly regulated by the state. The broadcast sector, in particular, was restricted to only government-managed television and radio operations throughout the first five decades after 1947. Pakistan Television (PTV) and Pakistan Broadcasting Corporation (PBC), both owned by the state, remained the sole means of mass broadcasts for current affairs during this time.

This monopoly was singularly instrumental in helping perpetuate military rule which took up more than half of the 50 years after independence. Military regimes were largely unimpeded by democratic resistance in the absence of mobilisation of independent public opinion through mass media. This offers interesting insights into Pakistan’s political evolution.

While the period under Zulfikar Ali Bhutto in the 1970s and later under Benazir Bhutto and Nawaz Sharif in the 1990s was freer for the media – allowing for the freest political atmosphere till then – it was not until the early new millennium that the biggest media reforms were enacted allowing for non-government, private broadcast media to emerge. The dozens of television channels and FM radio stations which subsequently came about fundamentally altered the contours of public opinion mobilisation and were directly responsible for the resistance to General Pervez Musharraf’s dispensation and the eventual return of democratic rule in 2008.

Pakistan’s media landscape has changed dramatically in the new millennium. The primary transitions have been from an officially controlled media to an independent, pluralistic one; from time-delayed news release and broadcasts to ones taking place in real time; from fixed media to mobile media and from media-driven news and information to citizen-driven contents. These changes have impacted people in a myriad of ways in terms of their perceptions of how representative the media is of their interests as well as its utility. The media has also been developing interests and agendas of its own thereby impacting politics and governance — sometimes threatening the very stability of the system.

The changes in the media landscape coincide with the political transition that Pakistan has experienced of late. The transition from the preceding century to a new millennium was ushered in by the military under a uniformed president. General Musharraf staged a coup in 1999 and stayed put until forced out in 2008. However, paradoxically, the media sector’s largest expansion in Pakistan’s history happened when he opened the airwaves to private ownership in 2002.

By the time civilian rule returned to the country in 2008, the number of independent television channels had gone from zero to over 70. By the onset of 2018, this number reached about 90 and included 36 current affairs channels broadcasting news and views 24/7, according to the Pakistan Media Regulatory Authority (Pemra). In the same period, the number of FM radio stations went from none in the private sector to close to 150 now. Internet and social media have since become entwined with the mainstream media. Newspapers and magazines have also proliferated in the same period (2002-18) mainly because the federal government devolved the authority to issue declarations for them to provincial and district authorities.

Military rule in the new millennium may have effected and facilitated a massive expansion in the media landscape (85 per cent of the media today did not exist when Musharraf took over), but public opinion regards the media as less restricted under the civilian era that has followed him rather than under his own regime. The same holds true for the last millennium: media is considered ‘free’ under civilian dispensations but ‘unfree’ under the military ones. The survey shows that periods under military dictators (Ziaul Haq, Yahya Khan and Ayub Khan) are seen as being the worst for the media, which is seen as having fared better under elected leaders (Asif Ali Zardari, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, Benazir Bhutto and Nawaz Sharif).

The media, however, is viewed as ‘not free’ under all but one regime by more than one in three respondents. It is considered the freest during the Jinnah-Liaquat reign (by 52.47 per cent of respondents) followed closely by the Zardari years (when it was free according to 45.43 per cent respondents) and Nawaz Sharif’s governments (when it was free as per 43.51 per cent respondents). The least number of respondents (31.71 per cent) view the media as ‘free’ during the Zia years.

Whether ‘free’ or ‘unfree,’ the benchmark for a media’s effectiveness is how reliable information released from its various channels is considered. The survey reveals that around six times more respondents consider television as the most reliable source of information in Pakistan than those who consider it the least unreliable; over a third of the respondents think newspapers are the most reliable source of information and less than a quarter think they are the least reliable. For one in three, Internet is the most reliable source of information while about one fourth consider it the least reliable. So, it is a mixed bag.

On the other hand, only marginally fewer people lay their stock in the government and the clergy being the most reliable sources of information as compared to those who view these two as the least reliable. Private sources of information such as television channels, newspapers and Internet are trusted more than official sources.

Based upon 11 pre-identified key sources of information, television is considered as ‘highly reliable’ by the highest number of respondents (54.8 per cent) followed by newspapers (by 34.61 per cent respondents) and the Internet (by 30.12 per cent respondents). Other sources considered ‘highly reliable’ include social media (by 29.27 per cent respondents), radio (by 24.32 per cent respondents) and government/public announcements (by 23.85 per cent respondents). Only 22.05 per cent of respondents consider educational institutions, 20.37 per cent regard mosques/places of worship, 20.01 per cent deem clergy/religious groups, 18.88 per cent view educational curricula and 16.86 per cent see community centres as ‘highly reliable’.

Conversely, 29.94 per cent respondents consider community centres as the ‘least reliable’ sources of information, 28.49 per cent have the same opinion about educational institutions and 28.22 per cent regard educational curricula similarly. Other sources considered ‘least reliable’ include mosques/places of worship (by 27.57 per cent respondents), clergy/religious groups (by 27.15 per cent respondents) and social media (by 25.24 per cent respondents).

The media is supposed to be the guardian of public interest simply because interests of governments and other groups vary over time. In countries where the executive, Parliament and the judiciary are failing to perform their duties, the media becomes the last bastion of support for the suppressed and the marginalised. People expect the media to be ethical by being truthful, accurate, independent, fair and impartial when it comes to highlighting public interest and holding the state/government accountable for the failure to enforce fundamental rights.

On this account, the survey shows that government-owned media, including television and radio, is considered the most ethical medium by 42.63 per cent of the respondents while only 25.37 per cent of them consider privately-owned television and radio as ethically strong. Online mediums such as websites and social media together enjoy the confidence of 52.72 per cent respondents for their ethical strength; 23.64 per cent respondents regard these two as ethically ‘very weak’.

Print media, including newspapers and magazines, are considered the most ethical mediums by around six times more respondents than those who consider it least ethical. In order of preference as ethical mediums, government-owned broadcast media is most highly regarded, followed by online platforms and privately-owned broadcast channels.

One explanation for this public perception could be that private television is seen as hysterical and sensationalist while government media is viewed as relatively calmer in its disposition and treatment of news. Political parties also find private television more amenable to extending their hysterical soundbites driven by their necessity to exaggerate the shortcomings of their rivals.

Because news media in general and electronic and online media in particular have become cheap sources of access to information for tens of millions of people, as opposed to the street politics of the last millennium; it is not surprising how powerful political, social and other influential groups in Pakistan’s socio-political landscape ‘use’ the media to their advantage.

The survey shows that some interest groups with resources and muscle, inevitably, are more adroit media users than others: government, political parties and military are viewed as the best users of television, radio, Internet, social media, newspapers, mosques and the clergy while communities and educational institutions and curricula are capable of using the media to a much lesser degree. Non-state actors such as militant groups are also seen to be relatively more adept at exploiting these mediums to advance their agendas.

According to 53.04 per cent respondents, television has been most effectively used by the government, 19.66 per cent of them believe it is the military that is using television the best and 15.26 per cent think that political parties are doing it better than anyone else. Another 6.89 per cent feel non-state actors have best used television for their agendas.

Radio is perceived by 30.95 per cent respondents as best used by the military, 29.35 per cent of them believe the government is using this medium the best and only 12.63 per cent and 22.15 per cent, respectively, feel non-state actors and political parties use it best.

Newspapers are seen by 30.83 per cent respondents as best used by political parties; 28.68 per cent believe newspapers are best used by the government; 23.58 per cent say the military has used them best and 11.5 per cent respondents see non-state actors having made the best use of this medium.

Internet is best used by political parties (according to 27.51 per cent respondents), by the government (according to 21.87 per cent respondents), by the military (according to 21.35 per cent respondents) and by non-state actors (according to 18.23 per cent respondents).

Social media is best exploited by political parties (according to 27.86 per cent respondents), by the government (according to 21.01 per cent respondents), by the military (according to 20.66 per cent respondents) and by non-state actors (according to 18.48 per cent respondents).

Local mosques/churches/places of worship as a medium of communication is seen most effectively used by political parties (according to 27.32 per cent respondents), by the government (according to 23.17 per cent respondents), by the military (according to 20.91 per cent respondents) and by non-state actors (according to 19.15 per cent respondents).

The clergy as a means of communication is seen as exploited by political parties (according to 24.89 per cent respondents), by the government (according to 24.09 per cent respondents), by the military (according to 20.04 per cent respondents) and by non-state actors (according to 18.32 per cent respondents).

Irrespective of which interest groups best ‘exploit’ various types of media, Pakistani media consumers are quite discerning in their perceptions of which mediums of information are most representative of their interests. The survey shows that both official and private broadcast media (including television and radio) are seen by the respondents as more favourable to people than

Internet, social media and partisan media owned by political parties and religious groups. The respondents do not seem to make any significant distinction between public and private broadcast media in terms of being favorable to people. Simultaneously, more respondents view Internet and social media and media owned by political and religious groups as being unfavourable to them than those who think public and private broadcast media is unfavourable to them.

Privately-owned television channels are seen by the largest number of respondents (46.41 per cent) as favourable to them, followed by government-owned radio (by 42.94 per cent), private-owned radio (by 42.59 per cent), government-owned television (by 41.08 per cent), media owned by political groups (by 38.2 per cent), Internet and social media (by 36.73 per cent) and media owned by religious groups (by 36.33 per cent of the respondents).

Conversely, Internet and social media are seen by 10.86 per cent of the respondents as unfavourable to them followed by 10.56 per cent who believe media owned by religious groups is unfavourable to them. Media owned by political groups is viewed as such by 10.01 per cent respondents, government radio by 8.68 per cent respondents, government television by 6.79 per cent respondents, private radio by 6.69 per cent respondents and private television by 4.34 per cent respondents.

Newspapers, private television channels, Internet and social media are seen by a majority of respondents as most representative of their worldview while media owned by religious and political groups and government-owned broadcast media are seen by them as least representative of their worldview.

The most surprising part of the survey’s findings is that far more respondents think marginalised communities such as religious and ethnic minorities and persons with disabilities receive ‘favourable’ to ‘highly favourable’ media coverage than those who think these groups receive ‘unfavourable’ and ‘least favourable’ coverage. These perceptions could be misplaced if seen in the light of anecdotal evidence as coverage of these marginalised groups borders on the stereotypical rather than being representative of their place in the society. Perhaps the respondents confuse ‘pity’ and ‘patronisation’ with ‘representation'.

The survey does not indicate major surprises in terms of people’s perceptions of media’s role of being the guardian of public interest and its performance and professionalism in representing society’s interests. However, it does offer startling insights as to how people are able to see right through the veneer of media which allows various interest groups to manipulate and promote their agendas to the detriment of people’s interests.

Military, religious groups and non-state actors are seen as exercising undue levels of influence over the media in conveying their messages across to the people. This can only be translated as the media compromising public interests. That private television – which, by definition, is independent of government control – is seen as less reliable or ethical than government-run television can only mean that private media is falling short on not just its public duties but also of people’s expectations.

If the media makes compromises over its professionalism, people’s interests get hurt. In a country that is entangled in a long-running, ever-intensifying fight between representative and non-representative forces over the country’s mission statement and its destiny — this is deeply troubling.

The writer is a media development specialist focusing on advocacy, research and training, with a background in journalism.

Economy

Highs and lows: A people's view of Pakistan's economic evolution

By Rashid Amjad

At the time of independence, Pakistan was a very poor country. Its per capita income in 1950 was 350 rupees or, at the then exchange rate, just over 100 US dollars1. Today, Pakistan is classified as a lower middle-income country, its per capita income having increased almost fourfold over the last 70 years. Extreme poverty has declined from an overwhelming 80 per cent of the population to around 30 per cent today. At independence, literacy levels were near 10 per cent.

Today, they are at 58 per cent even though Pakistan’s human development indicators still remain among the lowest in the world. The population has also increased almost sevenfold from just over 30 million in 1947 [in West Pakistan] to around 208 million in 2017. This high population growth rate has been a major reason why Pakistan has not fully reaped the benefits of a rather impressive annual growth rate of around 5.5 per cent over the last 70 years.

Many will be disappointed to learn from this survey that, despite the almost fourfold increase in average per capita income since 1947, only around 55.05 per cent of the respondents feel that their family’s economic situation has improved. Far more worrying is the result that almost 23.4 per cent feel that their situation has deteriorated; 20.98 per cent say that it has remained the same. These results do not change across different age groups covered by the survey, suggesting that the findings reflect the view of successive post-independence generations. Nor do these results change between male and female respondents.

The survey’s results are as much a reflection of the worsening income inequalities, continuing high poverty, lack of decent job opportunities, high inflation and low income growth in the last three decades as they are of increasingly stressful living conditions — especially in urban metropolises where overcrowding, traffic congestion, pollution and the absence or irregular supply of basic amenities have worsened the quality of life for most people. This aspect is best reflected in that far more survey respondents living in rural areas – nearly 59.3 per cent – feel that their economic situation has improved (for rural Punjab, the number is nearly 70 per cent), compared to 47.91 per cent in urban areas.

There is also a clear inter-provincial divide, with people in Punjab (around 65 per cent) and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (almost 60 per cent) stating that their economic conditions have improved over the last 70 years, as against much lower numbers for Sindh and Balochistan (almost 35 per cent for each). Interestingly, nearly 60 per cent of the respondents in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (Fata) also feel that their families’ economic conditions have improved since independence.

Given that there was hardly any significant industry at the time of independence, it is not surprising that nearly 22 per cent of the respondents feel that industrialisation has been Pakistan’s most important achievement. What is equally significant – given the very low food grain consumption at independence – is that 20.5 per cent see attaining food security as the country’s most important achievement.

This result is reinforced with 14.35 per cent respondents considering the green revolution – in which the output of wheat and rice increased manifold due to new seed varieties – as Pakistan’s most important economic achievement. These results are almost similar for urban and rural areas. Given the lack of implementation and political commitment, unsurprisingly only 6.02 per cent consider the meagre land reforms carried out by Ayub Khan and Zulfikar Ali Bhutto to have been an important development.

Perhaps because it is still in its earlier stages, only 8.06 per cent of the respondents see computerisation as important (though if the question had been posed in terms of access to mobile phones, the response would have been very high). Given the important economic impact it had in the 1970s, we find that nearly 13 per cent – and nearly 35 per cent of those who live in Islamabad – consider nationalisation as the most important economic development. A slightly higher share, nearly 15 per cent, look at privatisation the same way. Clearly, both developments are considered significant in altering the growth performance of the national economy.

In keeping with a higher reporting of improvement in economic conditions by the rural respondents, we find that 56.59 per cent of the respondents rate agriculture as having improved compared to only 27.76 per cent who feel the sector has deteriorated since 1947. This is in sharp contrast to industry: while 42.23 per cent feel that it has improved, an equally high 41.34 per cent say that it has deteriorated, reflecting the sector’s high growth (albeit from a small base) in earlier decades and its much poorer performance (‘deindustrialisation’) in more recent decades. After the initial spurt, industry’s share of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has remained relatively stagnant.

A somewhat similar result emerges for the services sector, with 41.89 per cent reporting an improvement and 37.69 per cent reporting a deterioration. The latter response is perhaps a reflection of the sector’s growing informalisation and the fact that it has created mostly low-income, temporary jobs — in many cases, under poor and hazardous working conditions.

The survey results are distinctly favourable for changes in physical infrastructure, with 55.34 per cent respondents reporting a significant improvement in the communications sector. This result reflects the large investment that has been undertaken, especially by the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PMLN) government, in building motorways, highways and rural road networks.

The same appears to be true of the technology sector, with 53.53 per cent reporting an improvement, though this is not reflected in any significant productivity increases in the economy.

Within the social sectors, 42.14 per cent respondents feel that healthcare has improved but a very high 38.15 per cent also feel it has deteriorated in the last seven decades, reflecting the poor state of health services in the country. The performance of the education sector is looked at somewhat more favourably, with 50.49 per cent saying it has improved but a significant 32.43 per cent saying it has deteriorated. The former number best represents the large increase in enrolment in absolute numbers, compared to virtually insignificant enrolment levels 70 years ago; the latter shows the poor quality of education being imparted.

A clear message that emerges from the survey is that people find a sharp deterioration in the quality of economic management over the last 70 years. This is best illustrated by comparing their assessment of the current situation with that for the period between 1947 and 1951. An overwhelming 69.85 per cent view the government associated with Pakistan’s founder, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, and the first prime minister, Liaquat Ali Khan, as either ‘good’ (29.75 per cent) or ‘very good’ (40.1 per cent). Indeed, 80.85 per cent of those who are now over 70 years old view the government’s economic performance for those years as either ‘good’ or ‘very good’.

This result is not just a reflection of the very high regard that people of all ages and all provinces have for the founding fathers but also an acknowledgement of the enormous economic challenges and hardships that Pakistan overcame under their exemplary and honest leadership to set up a functioning state almost from scratch.

This result is in sharp contrast with the respondents’ view of the economic performance under the last Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) government presided over by Asif Ali Zardari, which only a total of 34 per cent judge as either ‘good’ (25.13 per cent) or as ‘very good’ (8.93 per cent). The results are somewhat better for the economic performance of the three PMLN governments under Nawaz Sharif, including its current tenure: 41.12 per cent respondents deem it either ‘good’ (26.17 per cent) or as ‘very good’ (14.95 per cent).

The unfavourable rating for PPP is certainly not true for its earlier government under Zulfikar Ali Bhutto in the 1970s and under Benazir Bhutto in the 1980s-90s, both of which are viewed much more positively. Over 53 per cent of respondents view the former either as ‘good’ (30.69 per cent) or as ‘very good’ (22.98 per cent). The evaluation of Benazir Bhutto’s PPP governments is very similar. Over 50 per cent of the respondents view them as either ‘good’ (31.27 per cent) or ‘very good’ (19.61 per cent). The earlier civilian governments (1951–58) are also viewed reasonably positively, with 35.54 per cent respondents seeing them as ‘good’ and 12.31 per cent as ‘very good’.

An interesting finding of the survey is that the respondents do not view the military rule of Ayub Khan as significantly different from the earlier civilian governments of the 1950s, which it had replaced. In terms of numbers, 47.37 per cent see the economic performance of Ayub Khan’s government as either ‘good’ (29.32 per cent) or ‘very good’ (18.05 per cent).

The result is very similar for the later military regime under Pervez Musharraf, whose performance, again, is not evaluated as being significantly better than that of the civilian government it replaced: 30.34 per cent consider it ‘good’ and 16.8 per cent ‘very good’. Of all the military regimes, that of Ziaul Haq is rated the lowest (as is that of Yahya Khan), with only 37 per cent respondents seeing it as either ‘good’ (25.51 per cent) or as ‘very good’ (12.3 per cent).

Perhaps the most significant result of the survey is that, on average, people view the economic performance of civilian governments as being better than that of military rulers. Even if one were to weigh the results by the number of years a government has held office, the findings do not change. Another striking result is the very poor opinion the respondents from Sindh and Balochistan have of Pervez Musharraf’s economic performance.

Across provinces, and not counting the extremely favourable ratings of the Jinnah/Liaquat period, the government of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto stands in first place, followed by Benazir Bhutto in second and civilian governments of 1951-1958 in third. For those aged 18–34 years, Ziaul Haq’s regime and the last PPP government are at the very bottom.

On which important issues have people judged the economic performance of a government? Clearly, those that hinder or help them overcome economic hardships as well as those that adversely or favourably affect their living standards and best meet their basic needs.

Given the poor state of public service delivery, it is not surprising that an incompetent and inefficient bureaucracy tops the list by a huge margin, with 80.94 per cent of the respondents being of the view that this factor is ‘important’ (33.99 per cent) or ‘very important’ (46.95 per cent) in economic management. This is followed by corruption – a bane for all people – and energy shortages which had reached crippling levels recently: 74.51 per cent and 73.65 per cent respondents, respectively, see these two as key (the sum of ‘important’ and ‘very important’) factors. Law and order follows at the fourth position, with 69.08 per cent seeing it as another important factor in economic management.

Even after 70 years of independence, the prevalence of a feudal culture is seen by 57.99 per cent of people as either ‘important’ or ‘very important’ in economic management. Human development, too, is regarded as a significant factor — with 65.32 per cent respondents seeing it either as ‘important’ or very ‘important’. It reflects the high priority people give to educating their children. Surprisingly, income inequality ranks somewhat lower — with 59.35 per cent respondents viewing it as ‘important’ or very ‘important’. This may well reflect a sense of acceptance among people that the state is unable to change the country’s highly inequitable economic order.

An important result of the survey is the relatively high number of respondents – 64.25 per cent – who are concerned about Pakistan’s dependence on foreign aid and loans, reflecting the high foreign debt the governments have incurred in recent years and the burden of repaying this debt. Given the pressure on the balance of payments with stagnant exports and rising imports, 73.19 per cent feel that trade imbalance is either an ‘important’ or a ‘very important’ issue.

A slightly lower share of the respondents, 64.59 per cent, feels that a low currency exchange rate is also either an ‘important’ or a ‘very important’ issue. Inconsistent economic policies are rated as ‘important’ and ‘very important’ by 64.42 per cent of the respondents. This last ratio is slightly higher in Punjab than in other provinces.

Viewed overall, there are no significant regional differences in these results: an incompetent and inefficient bureaucracy still tops the list in all provinces, with unfavourable responses from Punjab – at 83.42 per cent – being marginally higher than in other provinces. The only significant difference is the greater importance given to law and order by 74.58 per cent respondents in Balochistan and by a somewhat lower number – 64.7 per cent – in Sindh. This clearly reflects the volatile law and order in the two provinces.

It is also interesting that only 44.24 per cent respondents from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa give importance to the prevalence of a feudal culture in economic management. This is significantly low compared to the national average of 57.99 per cent.

Rising prices have an adverse impact on living conditions for the vast majority of people and are a major source of dissatisfaction with the governments of the day, which, rightly or wrongly, are held primarily responsible for the problem. It is not surprising, therefore, that 63.24 per cent of the people surveyed feel that the government or the state has failed to control prices. More than half of the respondents are of the view that the state’s polices have been unsuccessful in terms of equitable distribution of farmland and wealth, taxation, farmers’ welfare and relations between workers and industrialists.

Between 42 per cent and 48 per cent respondents feel that the state has been unsuccessful in employment generation, women’s participation in the workforce and infrastructure development. The respondents’ evaluation of the lack of success in women’s labour force participation is not significantly different among women respondents or among those aged 18–34.

The lack of success by the government or the state in addressing people’s key economic concerns is underlined by the fact that almost 80 per cent of the respondents view the contribution of the government sector to the economy as being either ‘highly significant’ (42.84 per cent) or ‘significant’ (36.11 per cent). This is followed by the private sector which is seen as ‘highly significant’ by 23.99 per cent respondents and ‘significant’ by 50.56 per cent of them. The non-profit/non-government sector is regarded as ‘significant’ by 42.88 per cent respondents and ‘highly significant’ by another 17.97 per cent. Foreign states and institutions are seen as ‘highly significant’ by 21.35 per cent respondents and ‘significant’ by 38.86 per cent of them.

Conclusion

How do the results of this public perception survey stand up to, or differ from, the broadly held view of Pakistan’s economic performance?

There is little doubt that Pakistan overcame seemingly insurmountable challenges at the time of independence when many had doubted its very survival, especially those who had opposed Partition. Yet, the country has never fully realised its true economic potential. Between 1960 and 1990, it was among the world’s 10 fastest growing economies. Over the next 30 years, it found itself being overtaken decisively not just by the rapidly growing East Asian ‘miracle’ economies but also by China, then India and – after the results of the latest population census – Bangladesh.

It is this loss of earlier momentum and the accompanying disappointment that is reflected in the rather low proportion of people surveyed – just over half – who state that their economic conditions have improved since 1947 despite a fourfold increase in per capita income and great decline in poverty. Yet, the survey clearly identifies significant economic achievements: industrialisation, food security, the green revolution and – though not as significant as expected – the advent and spread of new technology.

But why has the country not realised its true economic potential? Significantly, a key factor in this regard has been the continuing war in Afghanistan, its spillover on the security situation in Pakistan and the resulting loss of investor confidence. Unfortunately, the Afghan war has not been mentioned in the survey questionnaire.

Still, the other key factors identified are telling. Above all others, the identification of an incompetent and inefficient bureaucracy and the considerable importance given by the respondents to the role of the state in economic development show, à la Hamza Alavi’s thesis, that the “overdeveloped state” has become increasingly dysfunctional and has resulted in unfavourable growth and development outcomes.

The survey results differ significantly from the broadly accepted view that Pakistan’s economic performance has been much better under periods of military rule than under civilian governments. While respondents are very critical of the economic performance of the last PPP government, they also rank the same party’s performance under Zulfikar Ali Bhutto and Benazir Bhutto higher than that under Ayub Khan and Pervez Musharraf. Economic performance under Ziaul Haq’s regime is viewed poorly but the performance of the PMLN governments is rated, at best, ‘fair’ rather than overwhelmingly ‘good’ or ‘very good’.

One can only infer from the survey’s results that people consider civilian governments more inclusive in decision making and more likely to evenly spread the gains of economic growth and development than the military ones — even if their economic performance in terms of GDP growth is less impressive than that of military rulers.

Another revealing result that emerges from the survey – again, contrary to the generally held view – is that far more people in rural areas than in urban areas report an improvement in their economic conditions since independence. This does not mean that per capita incomes in rural areas are higher or poverty levels lower – which certainly they are not – but it does show that the tensions and pressures of urban living have taken a toll on those living in the cities.

While more favourable economic policies, including higher prices of agricultural goods, increases in non-farm rural incomes and overseas remittances (with more overseas migration from rural than urban areas) may have helped reduce the rural-urban divide, what the survey’s results bring out is that cities have not served as engines of economic growth and certainly not of happiness or contentment.

An important contribution of the survey is that it brings out stark inter-provincial differences, especially among people living in Sindh and Balochistan who feel they have not enjoyed the gains of growth and development compared to those in Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Sindh and Balochistan are also far more critical of the economic performance of military rulers.

The survey offers a mine of information that needs further and closer analysis. Moreover, its important – and sometimes startling – results warrant closer attention from economists and economic historians. Most importantly, they demand decisive action by policymakers and politicians in order to put the economy back on a path of high, inclusive and sustainable growth.

The writer is a professor of economics at the Lahore School of Economics and a former vice chancellor of the Pakistan Institute of Development Economics.

Law and justice

In the people's court: Public perceptions of crime and punishment in Pakistan

By Sadaf Aziz

Pakistan’s legal history cannot be neatly separated from its political history, even in the ways that academic disciplines have been able to separate the two while describing other parts of the world. Here, at least, one strand of this complicated story tells us that the very origins of Pakistani statehood can be traced to the breakdown of constitutional negotiations between the main political players in British India. A little further back in the past, the limited Indianisation of the justice system, and the introduction of self-government during the last decades of colonial rule, produced a legal and judicial architecture in which the attainment of justice was secondary to the maintenance of centralised control over a disparate territory and fragmented population.

Much of this system of mixed and fragmented justice has been inherited by Pakistan and has survived since independence. Our constitutional history is also fragmented: the highest law of the land has been held in abeyance, abrogated, amended and renewed multiple times. While there is no guarantee that a more stable constitutional history would have addressed the functional flaws that constrain our judicial system from being responsive to social demands and people’s problems, we nonetheless remain saddled with the direct results of our chaotic relationship with the constitution.

As public discussions in Pakistan are increasingly focused on competition between different branches of government, this Herald-British Council survey allows us to cast an eye upon the historical provenance of continuing institutional conflicts, as well as the broader interactions of a citizenry with judicial structures. The survey results discussed here reflect perceptions about judicial performance and the broader architecture of Pakistan’s legal system. The picture that emerges is one that immediately suggests apprehension.