Dr Shahid Masood started his talk show on January 24, 2018, on the NewsOne television channel in his usual cryptic style. He called Prime Minister Shahid Khaqan Abbasi an intelligent man who had taken a wise decision by appointing a certain jurist as prosecutor general of the National Accountability Bureau. “Otherwise, [Abbasi] would have been arrested and handcuffed upon his return from Davos [Switzerland, where he was attending a conference],” Masood said. “Aik aur lohay ka chana (another bitter pill swallowed),” he said, without explaining why the prime minister would have been arrested and who was making him swallow a bitter pill. “This whole political situation in the country should be seen this way … ”

He left his sentence incomplete. Before he discussed politics, he said, he wanted to make a request to Chief Justice of Pakistan Justice Mian Saqib Nisar. He said he did not know if the judges watched his show but requested his audience to convey his message to the Supreme Court or, for that matter, any other court in the country. He also asked the Federal Investigation Agency (FIA), the Military Intelligence (MI) and the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) to investigate what he was going to say and take action.

He then drew a deep breath, tapped his right hand on his desk and started speaking slowly and deliberatively: “… the Punjab government has lied about the murderer of Zainab [the little girl who was raped and killed in Kasur city in January this year]. Utter lies, a pack of lies. And I am saying this with utmost responsibility.”

Masood next mentioned his recent visit abroad. “When I went abroad a few days ago,” he paused, “in fact, I came back only yesterday morning.” He pondered for a microsecond and resumed, “I returned on the morning before yesterday.”

Details of his foreign visits over the last one and a half years followed. He said he had been to Lebanon, to Syria, to the Kurdish towns of Kirkuk and Erbil in Iraq as well as to Tunisia, Libya and Yemen to study the conflicts there first-hand. “I could not share my location or my photos because … there is so much chaos there that you cannot trust anyone,” he said. “If the rulers came to know that I was at those places, they would have had me killed through someone there,” he said, laughing.

He also mentioned that he was a trained doctor in medicine and had pursued his postgraduate studies at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University in the United States, where internationally renowned scholar Vali Nasr was his thesis supervisor. After this long diversion, apparently to establish his credentials as an intrepid journalist and a distinguished scholar, he finally went back to talking about the Kasur incident and said he heard it being discussed everywhere while he was abroad.

“[Zainab’s murderer] Imran is neither a mason nor is he mentally sick,” Masood eventually said and raised his voice, gesturing with his hand as if he was pointing to something. “The thing that I am now going to say, I am saying it addressing Mian Saqib Nisar directly,” he said and looked straight into the camera. “[Imran] is an extremely active member of an international mafia or gang that has the backing of Pakistan’s high-profile and powerful personalities,” he said.

He looked at his co-host, took a long pause and resumed: “And this man has at least 37 bank accounts. Most of them are foreign currency accounts. This man, who is being presented as mad and mentally sick, has 37 accounts,” he repeated for emphasis. “The accounts he operates have transactions in euros, dollars and pounds from abroad … this is a game involving hundreds of millions [of rupees]. He has the support of important political and non-political personalities. This man is a member of a racket involved in [trading] violent child pornography.” Later, Masood would add that a federal minister was among Imran’s backers.

Social media went crazy over his ‘revelations’. Screenshots of a sheet of paper carrying details of Imran’s national identity card, his cell phone numbers and information about his alleged accounts soon started doing the rounds on various news sharing platforms.

Chief Justice Nisar also took note, as desired by Masood. He asked the talk show host to appear before the Supreme Court immediately and give evidence, if there was any, of his allegations.

When Masood came to court, the only ‘proof’ he gave to the chief justice was a piece of paper on which he reportedly wrote the name of the federal minister allegedly supporting Imran. After his court appearance, he told news reporters that he had evidence to prove all his claims.

Justice Nisar seemed to have taken Masood’s allegations seriously. He set up a high-level committee to investigate and told Masood to give its members proof of what he had said on his show. The committee would summon him multiple times over the next two days but each time he would have a different excuse to avoid appearing before it.

His entire story then collapsed.

The investigators appointed by Justice Nisar found no bank accounts that Imran operated. The State Bank of Pakistan endorsed their findings in a public statement issued on January 26, declaring that Imran had no “local or foreign bank account”. But Masood and some other talk show hosts still continued to repeat the allegations in the face of evidence to the contrary.

Embarrassed, the court sought advice from some of the most seasoned and well-known journalists. Many of them suggested that Masood should be let go after he apologises; others said he should be banished from television for spreading falsehood.

In the end, he neither apologised nor was he taken off air.*

Masood has faced much worse in the past. In his BOL News show on January 24, 2017, he alleged that two ministers – one who then handled the finance department and the other who at the time looked after the defence department – were summoned to the army headquarters in Rawalpindi, and given a shut-up call for implicating the military leadership in political and judicial developments around the then prime minister Nawaz Sharif’s trial over his allegedly illegal offshore properties revealed by the Panama Papers. Ishaq Dar, one of the two ministers, moved the Pakistan Electronic Media Regulatory Authority (Pemra), which banned Masood’s show for 30 days and imposed a fine of one million rupees on the television channel for airing baseless allegations “with the malafide and ulterior motives of attacking the integrity of the federal minister”.

His show was also suspended in 2016 for 45 days after he accused the then Sindh High Court chief justice, Sajjad Ali Shah, of taking bribes. He alleged that the judge’s failure to honour a commitment made to his alleged benefactors had led to the kidnapping of his son.

That these stories – and many others that Masood has told over the years in his shows – have been proven false, fabricated and without any basis whatsoever has done little to dent his reputation as a much watched and followed talk show host. He has 507,000 followers on Twitter, his show on NewsOne has a Facebook following of 172,493 and one of his two unofficial Facebook pages is followed by 164,678 people. If nothing else, these followers ensure that any news he peddles stays alive in some form or shape in some corner of the media.

And Masood is not the only practitioner of this dark art. There are others who have a much bigger fan following and thereby a much larger impact on public opinion. One of them, Dr Aamir Liaquat Husain, has been banned multiple times from appearing on television for spreading false news.

Mesha Saeed came to Pakistan along with her husband Ahmad Waqass Goraya and their son, Arastoo, towards the end of 2016 from the Netherlands, where they live. They were visiting to attend the wedding of Goraya’s sister in Lahore.

After the wedding, Mesha went back to the Netherlands where she studies pharmaceutical oncology but her husband and son stayed back. One night in early January last year, she received a call from Goraya’s brother. He sounded worried. Goraya had not returned home and it was already long past midnight in Pakistan. Tired after a long day at work, she told her brother-in-law not to worry and went to sleep.

What leads people to believe in such news is their readiness to remain unquestioning about anything that conforms to their political world views.

Mesha would discover the next morning that her optimism was misplaced. Goraya had become a missing person.

She returned to Pakistan immediately. By that time news about some other people – all human rights activists and social media junkies like her husband – having gone missing had become public.

It was the most difficult time of her life, she says. For days, she could not eat or sleep properly. When a ‘source’ informed her on January 11, 2017 that “her husband’s name has been cleared” and that he would come home soon, it was a moment of great joy for her. She finally sat down to have a full meal that night with her in-laws. Their happiness was short-lived.

As they were having dinner, a relative called. He asked them to watch a television channel where a talk show host, Orya Maqbool Jan, was going on and on about how Goraya and other missing activists had blasphemed through their social media posts. Jan particularly highlighted three Twitter accounts, Bhensa, Mochi and Roshni, as the source of the allegedly anti-Islam, blasphemous content. He accused Goraya of being the administrator of one of the three accounts. “Why do you need to commit blasphemy to be called human rights activists?” asked Jan.

“I was gutted. I felt hopeless,” Mesha recalls. “Everyone in the house started crying because we knew what this meant — that Waqass was never going to come back.”

Several news channels would air the same accusations over the next few days. On BOL News, Dr Aamir Liaquat Husain claimed repeatedly that the missing activists were in fact Indian agents who had run away to India after their anti-Pakistan and anti-Islam activities had been revealed. “They are present in India … they are being supported by RAW … They have not actually been abducted,” he said again and again. “The allegations that they have been abducted are being made to malign the military, the agencies and the ISI.”

A similar campaign simultaneously started on social media. In posts on January 9, 2017, an online forum, Pakistan Defence, displayed photos of three missing activists – Salman Haider, Ahmad Waqass Goraya and Aasim Saeed – with a caption in Urdu that read: “A group of atheists running blasphemous pages on Facebook has been defeated. Meanwhile, the so-called secular elements are giving the whole matter a political colour through media.”

Hashtags such as #HangSalmanHaider and #WhoAreTheyDefending – a reference to those who were demanding the return of the disappeared – soon started trending on Twitter. Overnight, banners also appeared in several cities, including Gujranwala and Rawalpindi, demanding death for the missing activists.

One Muhammad Tahir, the self-proclaimed head of an unknown organisation, the Civil Society of Pakistan, went as far as seeking the initiation of blasphemy cases against them. He submitted an application on January 16, 2017 at a police station in Islamabad to book Haider, Goraya and others who had disappeared with them under Section 295-C of the Pakistan Penal Code, which covers insults to the Prophet of Islam and carries the death penalty.

Four of the five missing activists came back home by January 28, 2017. Three of them, including Goraya, immediately left the country. Haider stayed at his home in Rawalpindi for a couple of weeks before he, too, left Pakistan. All of them feared for their lives.

The fears put paid to plans made by Mesha and Goraya to eventually settle in Pakistan. They were concerned about the future of their son in the Netherlands. He felt isolated on foreign soil. “My husband is now a marked man,” Mesha says. “His face is all over social and mainstream media. We fear he might be killed by someone in the name of Islam.”

The scare has persisted in spite of the fact that the Islamabad High Court recently cleared the missing activists of blasphemy charges. The court’s ruling came in February this year, after months of investigation ordered by a judge hearing a petition filed in February 2017, in which the petitioner had sought the trial of the activists for blasphemy. The FIA’s investigators had told the court in December 2017 that the activists “were not involved in blasphemy”.

Lately, Husain also acknowledged their innocence. After leaving BOL News a couple of months ago, he apologised for purposively hurting “several personalities” through his show. He claimed he had done it all at the behest of the channel’s owners.

The acquittal and the apology do not mean much to Mesha. The allegations of blasphemy against her husband continue to swirl around with no end in sight. “The fake news which spread throughout social and mainstream media about my husband being a blasphemer has forever endangered his life. Nothing can undo it.”

Husain was in his characteristically aggressive, mocking mood on his BOL News show on January 19, 2017. “Do you think people supporting the blaspheming [activists] through their writings and speeches are right?” he said, angrily. He marked one of their defenders, lawyer and human rights activist Jibran Nasir, as a target for his vitriol and went to the extent of claiming that the so-called blasphemous social media accounts were actually run by Nasir.

Civil society organisations, journalists and the families of the missing activists by then were already protesting that the accusations of blasphemy were baseless. Yet, BOL News continued levelling the same accusations over the next two weeks, showing little by way of evidence except a few screenshots of some social media posts.

In an effort to rope in the institutions of the state to counter these allegations, Nasir complained to Pemra against BOL News and Husain. He accused the channel and the show’s host of running a “malicious, defamatory and life endangering campaign” against him and the missing activists.

Pemra banned Husain on January 26, 2017. “[He] wilfully and repeatedly made statements and allegations which [are] tantamount to hate speech, derogatory remarks, incitement to violence against citizens,” a Pemra statement noted. It also said he was making an unsubstantiated “accusation of being anti-state and anti-Islam” against various individuals.

This did not stop the accusations from spreading. The Twitter hashtag #WhoAreTheyDefending continued to question the motives behind protests for the disappeared. Another account, @NewPakistan2020, with more than 38,000 followers, tweeted: “All Pakistani social media users know Bhensa’s language against our Prophet (pbuh) and @MJibranNasir asks for proofs.”

Accusations of blasphemy against the missing activists, as Nasir pointed out, first appeared on Pakistan Defence. The administrators of this digital forum describe it as an “online community with an objective to provide a platform for debates and discussions on topics regarding but not limited to defence, national security, military, industry and global security issues”. The community, the administrators claim, has 70,000 registered members and an audience of 20 million visitors across different social media platforms. The name of the forum notwithstanding, they deny any link to any military or security organisation.

Pakistan Defence suffered a serious setback in November 2017 when its official handle was suspended by Twitter. The action was taken after the forum posted a doctored photo of an Indian student activist, Kawalpreet Kaur. In her original photo, she held a placard in front of Delhi’s Jama Masjid to protest against mob lynching. The placard read: “I am a citizen of India and I believe in secular values.” In the changed photo, the text on the placard read: “I am an Indian but I hate India because India is [a] colonial entity that has occupied nations … ”

A Pakistan Defence administrator insists in an email exchange with me that the photoshopped image was uploaded due to “a human error”. The anonymous administrator also denies levelling accusations of blasphemy against the activists. “Sharing public debates is what we do and the opinions we share do not reflect the policy of Pakistan Defence forum,” is how he explains the posts carrying accusations of blasphemy.

It is not known if Pakistan Defence is included in the list of 45 Twitters accounts, 94 Facebook pages, 101 Youtube accounts and 15 Instagram accounts that the Pakistan Army wants the FIA to investigate and block. “These accounts are being operated by unauthorised individuals [who have] assumed the role of speaking on behalf of the armed forces and they have been gaining attention on social media, giving a misleading impression that statements posted from these accounts are official statements by the armed forces of Pakistan,” reads a news report about the army request, published on February 16, 2018.

Renowned Indian actor Paresh Rawal went on a rant on his Twitter account around 4 pm on May 17, 2017. Criticising Indian writer and activist Arundhati Roy, he wrote: “Her birth certificate is a regret letter from maternity ward!”

He referred to an incident in Indian-administered Kashmir where the Indian army had tied a young Kashmiri to the front of a jeep to humiliate him and to show other youngsters that similar treatment awaited them if they pelted stones at Indian military personnel. “Instead of tying stone-pelter on the army jeep tie Arundhati Roy!” Rawal suggested.

His tweet, shared thousands of times, initiated an aggressive debate between his supporters and those of Roy; but what had sparked his outrage to begin with? It was a statement attributed to Roy in which she had reportedly said: “Even 70 lakh Indian army cannot defeat the Kashmiris.”

The statement was carried by several Indian news websites known for their right-wing, Hindu nationalist slant. In Pakistan, both Geo Television and the daily The News published it on the same day – May 16, 2017 – on their websites. The latter also published it on its front page the next morning, quoting the Indian media as its source.

There was a small problem with the statement: it was fake.

Speaking to Delhi-based news website The Wire, Roy vehemently denied having made it. The website of Geo Television removed the report about it after this disclosure but the website of The News still carries its story.

So, where did the statement come from?

One of the first places where it appeared was the Times of Islamabad. A self-designated news agency operated from Lahore, the Times of Islamabad carried a report on May 16, 2017, on its website that said: “Speaking during her visit to Srinagar, [Roy] said India cannot achieve its objective in the occupied valley even if its army deployment raises from 7 lakh to 70 lakh, further adding that Kashmiris have remained committed with their anti-India sentiments from many years.”

As it turned out, Roy had never visited Kashmir.

The Times of Islamabad, in turn, had quoted Radio Pakistan as its source. The related link has since been removed from the website of Radio Pakistan but screenshots of its archives show that the news was indeed uploaded on its website on May 16, 2017 — the same day it appeared on the Times of Islamabad website.

The version of the news available on the Times of Islamabad website, however, carries many additions to the original story published by Radio Pakistan. Apart from recording Roy’s alleged statement about the Indian army, the Times of Islamabad story also said: “Taking a jibe at the Indian government she said that pity on the government which stops its authors from expressing their thoughts and put in jail those who raise their voice against injustices, however, sets free corrupt, rapists and other criminals.”

The Times of Islamabad is registered as a “Private Limited” company with the Securities and Exchange Commission of Pakistan. Its official address is that of a house in Satellite Town, Sargodha. Local residents there say the house belongs to a retired air force officer.

The website of the Times of Islamabad claims to enjoy one million views a month but several online tools indicate its total page views are less than a quarter of a million.

The “About Us” section of the website – which is full of typos – indicates that it has a special focus on “defence and military news, foreign policy and diplomacy”. The most important feature of the website, according to its own reckoning, is its op-ed section that carries the writings of “illustrious scholars and PhD researchers in the field of Politics and International Relations”.

Most of the news stories and op-eds carried on the website, however, are without a by-line — “News Desk” has penned them. In a telephone interview, Shahid Imran, the website’s designated contact person, claims several retired military officers and researchers from various universities contribute to the Times of Islamabad. He fails to name anyone in particular.

The scanned copy of a letter allegedly issued by the Directorate of Indian Military Intelligence, and stamped SECRET, started doing the rounds on Twitter and WhatsApp groups both in India and Pakistan on November 16, 2017. It was titled “Present Status of Motivation Among Personnel of Indian Armed Forces” and read like a damning indictment of the Indian military. It claimed that morale among Indian military personnel was going down due to several reasons, including an “exponential increase in cases of homosexuality” and discrimination among soldiers and officers based on their caste and religion. Curiously, not a single mainstream Indian media outlet reported that day that such a letter had been either written or released.

Pakistan and India’s mutual hostility has also offered fake news a perfect breeding ground.

Praveen Swami, a senior Indian journalist who has worked as editor for national security for The Indian Express newspaper, tells me in a telephone interview that he did not know anything about the letter. The additional directorate general of public information for the Indian military also issued a statement on Twitter, claiming the letter was fake.

It was first published by Daily Mail News, an Islamabad-based website, as part of an “exclusive” story that did not quote any sources, either on or off the record. Several mainstream news channels, including Dawn News, NewsOne and Abb Takk, broadcast the story later. Then it became a hashtag on social media – #DemotivatedIndianArmy – that trended rapidly through several Twitter accounts.

The Daily Mail News story was written by one Christina Palmer from New Delhi, with additional reporting by Anjali Sharma and Ajay Mehta. Research reveals that no journalist with the name of Christina Palmer works in Delhi. Her name, however, is mentioned by Cafe Pyala – a defunct blog that once critiqued Pakistani media – in a 2010 post about a network of websites purposively misinforming readers. The blog suggested that Christina Palmer is a fictional character.

Back in 2010, too, Daily Mail News had published several news stories that turned out to be fake. One of them claimed that the Indian intelligence agency, RAW, was behind spot-fixing by Pakistani cricketers during a 2010 tour of England. (Some mainstream Pakistani newspapers also carried the news without verifying it.)

The same year, Daily Mail News reported that the Indian military had “deployed 200 prostitutes” along the Line of Control to counter the “alarmingly increasing incidents of suicides and killing colleagues by soldiers of Indian army that are deployed in the Indian occupied Kashmir to fight the Kashmiris”.

Several attempts to reach the management of Daily Mail News through email remained unsuccessful. The editor-in-chief of Daily Mail News is one Makhdoom Babar. When I contacted him on the phone, he told me to send him an email with all the questions I had regarding the authenticity of his organisation’s news reports and the existence of Christina Palmer. I sent the email but he never wrote back.

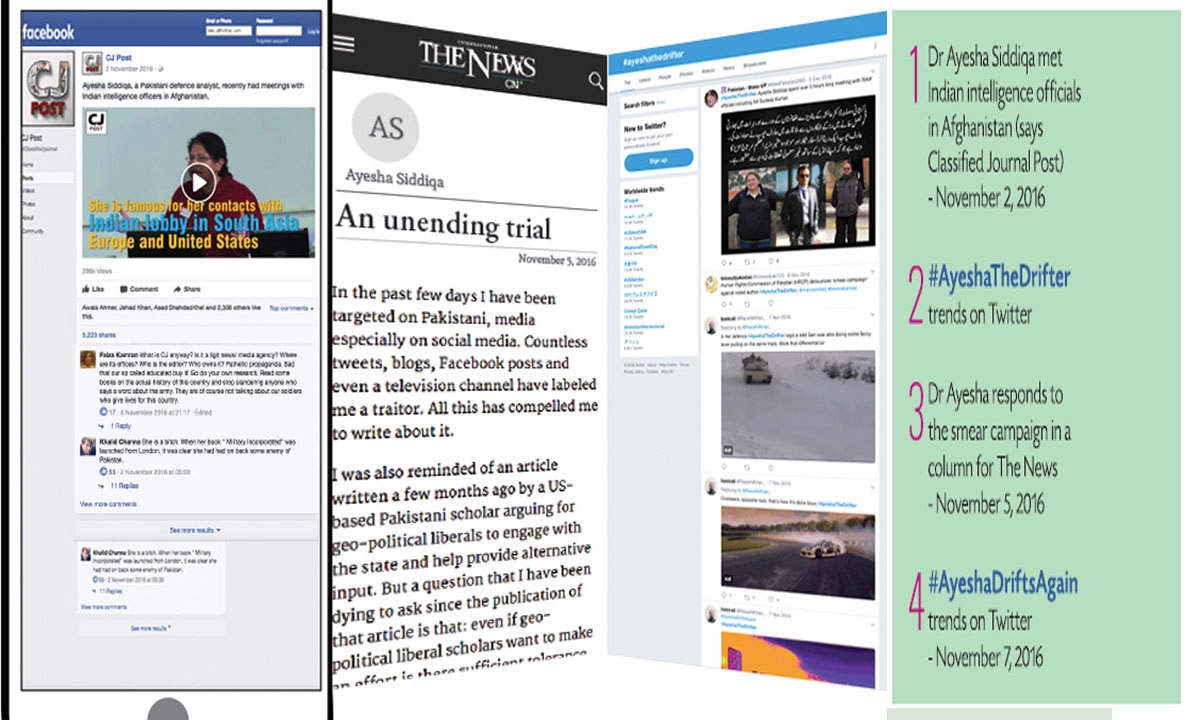

Dr Ayesha Siddiqa, a prominent research scholar and the author of Military Inc., a book on the Pakistan military’s business interests, was in London in October 2016 to attend a conference organised by Husain Haqqani, Pakistan’s former ambassador to the United States. A few days after the conference, while Ayesha was still in London, a previously unknown news outlet, Classified Journal Post, uploaded a video on Facebook, accusing her of meeting Indian intelligence officials during a secret trip to Afghanistan.

The video, watched and shared by thousands, consisted of a montage of Ayesha’s photos shown alongside photos of some unknown men labelled as Indian intelligence officials in Afghanistan. Not a single photo showed her meeting any of those men.

Ayesha wrote a response to the video in an article, An unending trial, that appeared in the daily The News in November 2016. She said she had not gone to Afghanistan secretly but to attend a conference along with six other Pakistanis including a former ISI chief. “The malicious campaign against me from approximately a hundred social media accounts on different forums – all sounding the same – is truly pathetic,” she wrote.

The website of Classified Journal Post has more than 160,000 followers on Facebook and more than 14,000 on Twitter and it promises to “bring those hot issues to [readers] that are ignored in the main stream media, News that needs equal attention”. One of its photo montages accuses Maryam Nawaz Sharif of trying to become prime minister “using shortcuts”. She is also alleged by the website to be supporting India, defaming Pakistan and endorsing blasphemy.

Most of the news stories carried by Classified Journal Post are written by one Janet Mayson. Others are written by “Web Desk”. No personal details exist about Janet on the website.

Most of the website’s so-called news videos are presented by foreign-looking women. Internet searches show that at least two of them are freelance actresses. One of them, Allie Madison, is featured on a freelancing website Fiverr which states that she is available to produce videos on any topic for a price as low as five US dollars.

The British Broadcasting Corporation’s (BBC) Urdu service claimed in a report published on January 13, 2017, on its website that the family of former prime minister Nawaz Sharif had remained the only owner of their London flats since the 1990s. The flats at the time were at the centre of an ongoing case at the Supreme Court.

Less than a week later, Pakistan’s state news agency, the Associated Press of Pakistan (APP), released a story claiming that the BBC had started investigating the reporter, Ather Kazmi, who had filed the news report on the ownership of the flats. “The BBC has been put into a very embarrassing situation,” the APP report said. It quoted unnamed BBC sources as saying: “The article carries nothing new. Our reporter misled the duty editor who thought the article was carrying new information.”

A news report being accepted as wrong would require retraction but the BBC did not do that — something the writer of the APP story seemed to realise. He went about offering a justification: “Now if we take it down, it will result into a bigger scandal and will make headlines,” he quoted the sources as saying.

The News carried a similar story in its January 19, 2017 edition. The story had no by-line and claimed that the BBC had accused its own reporter of misusing the platform of the British broadcaster and of playing into the hands of a Pakistani political party.

In order to strengthen its story, the newspaper also reported how the BBC’s Urdu service had faced “another big embarrassment in July 2015” when it was “called inefficient and loose” after one of its reporters had “sent a tweet mistakenly claiming the [British] Queen had died”. According to The News, the tweets were accepted as “a grave error of judgement” by the BBC itself.

Except the two cases are widely different — one concerns a staffer setting off the Twitterati through a personal mistake and the other seems to suggest that a whole media organisation was hoodwinked allegedly by a reporter bent upon mischief for personal gain.

The BBC was prompt to deny the APP and The News reports. “There is no internal investigation into this BBC reporter (Ather Kazmi),” it said in social media posts. “We stand by our journalism and are satisfied that this story meets our editorial standards including accuracy and impartiality.”

The BBC also rejected the suggestion that it was contacted by any Pakistani news organisation to inquire about Kazmi’s report. “Nobody has contacted the organization with regard to the story.”

The state news agency never retracted the story in spite of its categorical rejection by the BBC. The News, too, still carries the report on its website in its original shape, without any correction or clarification.

One of the most watched Pakistani news channels, Dunya News, reported in July last year that 158 Indian soldiers had been killed in a clash with Chinese forces in Sikkim. The channel cited China’s state-owned television channel, China Central Television, as its source.

Both Indian and Chinese officials quickly refuted the “groundless” news report. The denials did not lead Dunya News to retract the news, and it is still available on its website.

Mainstream media organisations, as is obvious from the many instances cited above, have often fallen to the allure of false and fake news stories. Senior government representatives, too, have sometimes been swayed by them.

Khawaja Asif, who was Pakistan’s defence minister before becoming the foreign minister in the middle of 2017, made international headlines when he issued a nuclear warning to Israel in December 2016. His hasty and unnecessary warning came after a website, AWD News, known for releasing fake news, published a fabricated story, claiming that Israel “will destroy” Pakistan if it sent “ground troops to Syria on any pretext”.

The foreign office also recently reacted rashly to a news report about the treatment of an Indian journalist who had written a story for an Indian news website, The Quint, about the Indian spy arrested in Pakistan, Kulbhushan Jhadav. The story claimed that two RAW chiefs knew that Jhadav was on a secret assignment and that they had opposed his recruitment for spying missions. The website retracted the story the next day, reportedly under pressure from the Indian government. Rumours on social media suggested that the reporter concerned had gone “missing”. Believing the rumours to be true, foreign office spokesperson Dr Muhammad Faisal tweeted: “Journalist Chandan Nandy who filed the story is “missing/gone in hiding”, was last spotted at Khan Market Delhi and since then has been untraceable for family and friends. Freedom of press?”

Nandy was fine but avoiding the media.

Bytes For All, a human rights organisation and a think tank that has offices in Lahore and Islamabad and focuses on information and communication technologies, issued a report (which I co-authored) in 2017 about Pakistan’s Internet landscape. “Cyber armies hired and organised by different state and non-state actors” have become a new phenomenon in Pakistan, the report said. “These cyber armies will manipulate truth and seed campaigns against individuals or like-minded groups to undermine their opinion by inciting violence, life threats and shrinking spaces,” it added.

Zarrar Khuhro, a senior journalist and talk show host who actively challenges misinformation and fake news on social media, cannot agree more. Calling fake news an endemic problem everywhere in the world, he says it must be seen as an active form of propaganda by certain quarters against their opponents. “What leads people to believe in such news is their readiness to remain unquestioning about anything that conforms to their political world views,” he says.

Indian journalist Praveen Swami sees the problem of fake news in a similar light. “The public is always eager to consume news that confirms their biases.” Fake news, thus, finds an active readership.

In the echo chamber of digital and social media, people like whatever they see as endorsing their own ideas and points of view, without bothering about authenticity and verifiability. This process receives a boost of validity when mainstream media becomes a part of it — often willingly. As Khuhro points out, many fabricated news stories are initiated on social media but they reach mainstream media due to a “breach of journalistic protocols”. Some fake stories in Pakistan have spread the other way round as well — starting on mainstream media and then spreading to social media.

Pakistan and India’s mutual hostility has also offered fake news a perfect breeding ground, says Swami. With mainstream media in both India and Pakistan willing to act as the official mouthpieces of their respective states, the fake news phenomenon easily moves into a space that can lend it both authenticity and credibility. “In such polarised environments, it is difficult for journalists to function independently and to continuously remain vigilant about the information they receive.”

For Abbas Nasir, a senior journalist who has served at senior editorial posts including as the editor of the daily Dawn, fake news is not something altogether new or novel. The past, he says, was not entirely without attempts, mostly by intelligence agencies, to plant fake or distorted stories in newspapers. Often these stories were aimed at discrediting a civilian politician or a political party or to “explain away a blatant [government] failure”.

Nasir, however, agrees that, without social media, disinformation or misinformation may not have attracted as much attention as it does today.

Alt News, an Indian website, is focused on debunking fake news emerging from the social media rumour mill on a daily basis. According to its co-founder Pratik Sinha, “much of the fake news in India is originated by right-wing Hindutva sources”.

He believes it is not really difficult to debunk fake news. “We use single frames in videos to find the original source of the visuals in case we suspect a video may contain fake images,” he says. To verify and cross-check news stories, Alt News stays in touch with government and police officials and continuously checks for facts on government websites.

No such project exists in Pakistan. Shaheryar Popalzai, a Karachi-based journalist who has just completed a fellowship with the International Center for Journalists in Washington DC, plans to launch one some day. His project, if and when it materialises, aims to provide an insight into how propaganda works in Pakistani social media. “What we have seen over the past few years is that a hashtag campaign starts on Twitter and all of a sudden hundreds of users start tweeting using the same hashtag,” he says. “Often, the text in one tweet is replicated by 20 other accounts which gives an insight into how organised these campaigns are.”

Aware of the impact that the same text and images tweeted and retweeted from many accounts can have on the reach and believability of social media posts, Twitter announced on February 21, 2018, that it was banning the use of “any system that simultaneously posts identical or substantially similar tweets from multiple accounts at once, or makes actions like liking, retweeting, and following across multiple accounts at once”.

Tools such as Alt News or Twitter’s ban on the tweeting of identical text by multiple accounts may or may not work in Pakistan. Nasir, who himself is a regular on social media, thinks it is never going to be easy to counter fake news, especially for journalists working on news desks. Verification of fake news is often impossible because journalists dealing with it are not always equipped with the technological tools and know-how to trace its origin, he says.

Yet, according to him, it is the responsibility of news organisations to ascertain if the story they are publishing or broadcasting has originated “from a trusted source with a track record of providing irrefutable facts”. If the news is plucked from other media organisations then, he says, “it is imperative we confirm it by cross-checking through more than one source”.

But Nasir concedes that only newspapers have the resources to do all this due diligence. Television and digital media in Pakistan seem “years away from” being able to filter fake news from real news. They do not have adequate staff to keep a check on fake news all round the day, he says.

So, what is the solution if there is any?

It is only after the number of discerning news consumers increases considerably that we will see the required checks put in place, Nasir says. “That expansion will be gradual.”

Note: *The Supreme Court put Dr Shahid Masood off air for three months on March 20, 2018.

The writer is a freelance journalist who is currently pursuing a masters in Journalism, Media and Globalisation in Denmark.

This article was published in the Herald's March 2018 issue. To read more subscribe to the Herald in print.