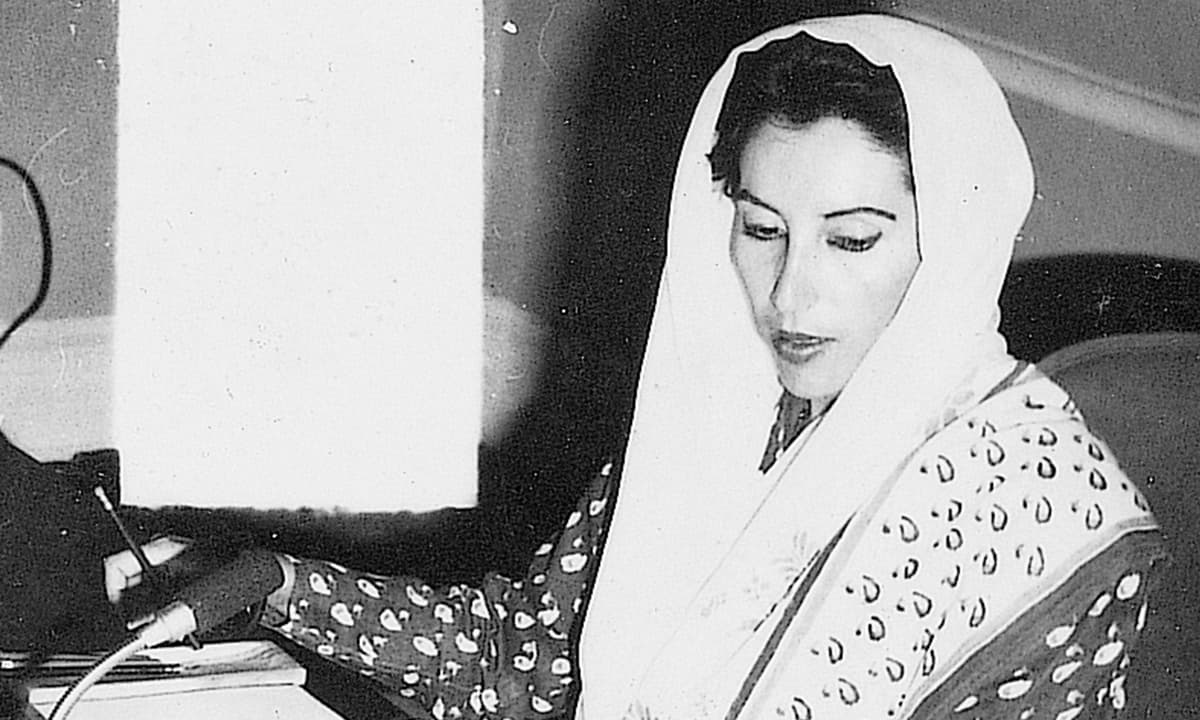

"Is it true that the prime minister of Pakistan is a woman?” asks the female Afghan protagonist of Samira Makhmalbaf’s 2003 film, At Five in the Afternoon. Although I had grown up in a Pakistan that witnessed the prodigal return of Benazir Bhutto against all odds, her miraculous rise, her predictable fall and her tragic end, it was this dialogue that really hit home what it meant to be a female head of the government of a Muslim country. She achieved the impossible and in doing so, inspired many others to believe in their dreams.

She was the first woman to rise to such high office in a country that only a few years earlier had passed a law to reduce the status of a woman’s testimony in court to half that of a man. She inspired millions of others all around the globe, not just with her unbelievable ascent to power but also with her charm and wit, her political intellect and her personality that refused to cower before the toughest of opponents. Her legacy as the most influential Pakistani lives on. She continues to inspire, enthuse and motivate women and the marginalised — both in Pakistan and abroad. For many, she is a symbol of hope, the poster person of dreamers and doers alike.

Having grown up in the shadow of her charismatic father, Benazir came into her own when Zulfikar Ali Bhutto was hanged in 1979. His death fueled her. His mission became hers and she carried on the fight for democracy in self-exile.

She was a brilliant student and excelled in oratory at Harvard and Oxford, inspiring not just minds but also connecting hearts — it was she who introduced the incumbent British Prime Minister Theresa May to Philip May who would become her husband. A shrewd politician and a committed family woman, Benazir has a legacy that refused to die down with her. As veteran journalist Hasan Mujtaba said in his poem, “Tum zinda hokar murda ho/Wo murda hokar zinda hai (You are already dead while you live/She is alive in her death).”

It was Benazir’s unapologetic attitude towards being a woman along with an elected leader that had many in a flux. In the 1980s, at a time when hyper-masculinity was the norm for women making it into a man’s world, she took on politics on her own terms. She actualised the phrase that ‘women can have it all’ by giving birth while also being the prime minister.

She had two brief stints in office (1988-90 and 1993-96) during which she was busier firefighting the conspiracies and allegations against her than actually accomplishing anything. She was a progressive visionary; her ideas, however, did not match that of the torturous administrative apparatus run by a bureaucracy made inefficient by a decade of Ziaul Haq’s military rule. She wanted better ties with India, her meetings with Rajiv Gandhi are well remembered as a means to carve a new roadmap to peace. But this, of course, did not go down well with the military establishment.

She had an ambitious economic agenda but she was not able to realise much of it, partly because of the friction with the army, partly because of opposition from political players such as the Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM) and Nawaz Sharif, and partly because of the incompetence and corruption of her own party. Most of her time in power was spent battling for survival against the machinations of those opposed to her, including the then presidents of the country, who were constantly trying to bring down her governments.

Benazir faced constant character assassination, perpetual resistance from the mullahs who would try to stir up the public by proclaiming that a government headed by a woman was un-Islamic and persistent refusal by army generals to salute a female prime minister. Yet she managed to leave behind a legacy of commitment to democracy, economic empowerment of the downtrodden and social equality that is rivalled by only the one left by her father.

In spite of the bureaucratic machinery that hindered many of her ideas, she left in her wake the Benazir Income Support Programme that has proved a welfare lifeline for those on the edges of society. Though not established directly by her, it was a result of the ideas she had initiated and was thus named after her. She set up the Lady Health Worker Programme that has become the backbone of the family healthcare system across Pakistan.

She also promoted the idea of higher education and – though not in her term in power – many years later it germinated into the Shaheed Zulfikar Ali Bhutto Institute of Science and Technology (SZABIST) that now has multiple campuses across Sindh and has expanded into the teaching of law, liberal arts and humanities as well.

Then there are hospitals, schools, roads and many other development initiatives that go unnoticed in the larger political events. She could not get due credit for many of them as they were initiated by her governments but, due to her shortened tenures, were completed by other administrations. Some of her achievements came to light and were acknowledged after her death — as is the case with a posthumous United Nations Human Rights Prize conferred on her in 2008.

Though not free of corruption scandals – something she faced numerous cases for – she was able to rise above those in death, if not in life. Her courage and defiance, her resilience to rally on even in the face of death threats and terrorist attacks have become symbolic of what it means to be a woman in Pakistan. She was seldom respected by her opponents while she was alive but she is revered by all and sundry after her assassination.

Whether she wanted it or not, Benazir continues to reign on as the most influential Pakistani of our times, overshadowing sportspersons, rock stars, army generals and Islamist jihadists. As she was once quoted to have said, “I have led an unusual life. I have buried a father killed at age 50 and two brothers killed in the prime of their lives. I raised my children as a single mother when my husband was arrested and held for eight years without a conviction — a hostage to my political career.”

A phoenix that rose from the ashes time and again, Benazir proved herself, if she ever needed any proving, through her tragic death in a suicide blast at the height of her election campaign in 2007 as someone who would go to any lengths to achieve her ideals. Many will find it hard to digest that the most influential Pakistani around the world should be a woman but the fact remains: she was the first one of our political leaders who challenged terrorists publicly even when she knew that the price of that challenge could be her own life.

The writer is an assistant professor at the Arzu Center for Regional Languages and Humanities at Habib University.

This was originally published in the Herald's August 2017 issue. To read more subscribe to the Herald in print.