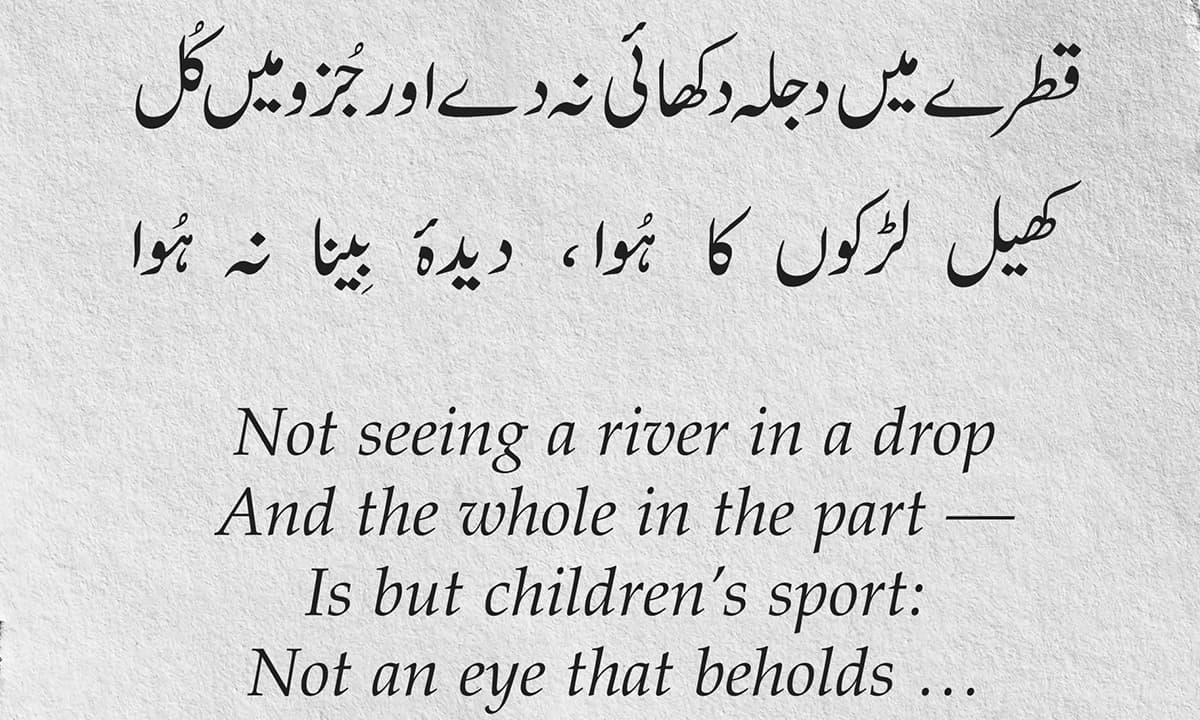

In one of his ghazals, Mirza Ghalib provokes us in the dancing sparks of his poetic craft:

This provocation, rich in its cosmic thrust and embodied as it is in a telltale wit and a commanding grip on the Urdu idiom, served as a philosophical inspiration for Faiz Ahmed Faiz — a young incarcerated Faiz.

Writing the preface to his poetry collection Dast-e Saba (Hand of the Breeze) from Hyderabad’s Central Jail in 1952, Faiz pondered on this verse, and in the course of his explication articulated the core literary doctrine of those we call progressive writers —

“Had Ghalib been living in our own times, in all likelihood some critic would have shouted out saying that he has insulted children’s games; or that he seems to be a supporter of propaganda in literature — since issuing an instruction for the poet’s eye to see a river in the drop is explicit propaganda.

“A poet’s eye is concerned, so would the censure go, with beauty and beauty alone … and this business of seeing or showing rivers in drops may well be the trade of a philosopher or a sage or a politician; it is not the calling of a poet …

“But fortunately or unfortunately, the art of poetry (or any art for that matter) is not children’s sport … A poet or a writer must not only see the river in the drop, he is equally required to make others see it. And more, if Ghalib’s ‘river’ is taken to mean the totality of life and the cosmic system of all that exists, then the writer too is himself a drop of that river.

This means that in partnership with innumerable other drops, on his shoulders falls also the responsibility to set and determine the direction of this river, its flow and figure, and its destination.”

Faiz was a ranking member of the All Pakistan Progressive Writers’ Association that held its first meeting in 1947 at the YMCA Hall in Lahore, with Ahmed Nadeem Qasmi serving as its secretary.

But before steering into factual history, let us attend to the pithy and eloquent pronouncement of Faiz — a pronouncement that constructs for us the very philosophical backdrop against which the checkered story of progressive writers is played out.

So here we have a theory of literature that pulls poetry, or any creative writing for that matter, down to earth and makes it an agency to serve a pragmatic function in society. In more crude terms – rather, frank terms – one can say that Faiz’s poet has been charged with the task of being an activist. He or she has the burden not only of seeing but also of showing.

If a creative act is not aimed at setting the direction and determining even the end, the telos, of that grand social system of which it is a part, then that act is lame, irresponsible, indulgent at best.

This is the crux of the matter, the grand picture, in the dramatic and intriguing story of the Progressive Writers’ Movement.

But this is the grand picture, the mural. We begin to see complexities of details when we work on a miniature.

One complicating element of these details is expressly ideological — the changes to be brought about by progressive writers had to be on Marxist lines; in the case of Faiz, more specifically on Marxist-Leninist lines.

Another complicating element is the stated discomfort of the Progressive Writers’ Movement with the Urdu literary tradition. The tradition was considered to be decadent, indulgent, and obscurantist, taking flights of fancy that left the ordinary, economically suffering human being behind on the earth, bewildered and oppressed.

If the tradition had turned putrid, what is the source of inspiration then?

The answer defines yet another central determinant of progressive writing — new inspiration has to be sought in the modern writings of the West, not only English writings such as those of James Joyce and Virginia Woolf, but also French writings such as those of Baudelaire and Mallarmé, and, of course, among others, Russian writings such as those of Gorky and Chekhov.

The Progressive Writers’ Movement operated in a doctrinal triangle whose three nodes were pragmatism, Marxism, and a western orientation. The seeds of all this are to be found already in that fateful collection of nine or so Urdu short stories, Angare (Burning Coal) that was published in Lucknow in December 1932. Written by four young authors – Syed Sajjad Zahir, Rashid Jahan, Ahmed Ali, and Mahmuduzzafar – this collection created a massive outrage.

It defied all tradition viciously: cultural, moral, literary, linguistic. One of its contributors, Ahmed Ali, owns up: “It was the first ferocious attack on society in modern [Urdu] literature … It was a declaration of war by the youth of the middle class against the prevailing social, political, and religious institutions.”

Indeed, with its Marxist leanings, Angare did radiate intense heat — the civil and religious establishment was simply outraged. India’s Urdu as well as English press was crowded with angry condemnations.

The All India Shia Conference in Lucknow called it a “filthy pamphlet” and demanded that the “book be at once proscribed”. One newspaper found nothing “intellectually modern” in the volume “except immorality, evil character and wickedness”.

There was a flurry of fatwas of abomination; donations were solicited to take the matter to the court; and more, demands were heard for stoning the authors to death and executing them mercilessly through hanging by the neck!

And then, barely three months after the publication of this accursed work of fiction, on March 15, 1933, Angare was banned by the government of the United Provinces — all but five copies were destroyed. Of the five remaining copies, three were delivered to the Keeper of Record in Delhi, and two were sent to His Majesty’s Government in London.

It is this scandal of short stories wherein lay the germs of the Progressive Writers’ Movement. Less than a month after the banning of Angare, a detailed statement from the authors drafted by Mahmuduzzafar was published in the newspaper The Leader.

This was an impassioned statement bearing the title, “In Defence of Angare. Shall We Submit to Gagging?” It argued for the significance and moral urgency of the stories in the volume, and included a “practical proposal” — namely, “the formation immediately of a League of Progressive Authors”.

Following this, on April 10, 1936, the All India Progressive Writers’ Association came into being in Lucknow, perhaps the most powerful and decisive Urdu literary movement of the 20th century. Zahir was its motive force, flanked by his comrade Ahmed Ali.

Despite periodic denials by the association, as well as by its Pakistani variant, that it had nothing to do with any political party, its link with the Communist Party of India (CPI) remained unveiled. It was this very CPI that voted in 1948 for the establishment of the Communist Party of Pakistan (CPP) and sent Zahir to Lahore for this purpose.

One here recalls the notorious Rawalpindi Conspiracy Case — the conspiracy led by Major General Akbar Khan in 1951 to overthrow with Soviet backing the government of Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan.

In March of that year an order was issued by Governor General Khawaja Nazimuddin for the arrest of Akbar Khan and of two pro-Soviet progressive writers whose support he had enlisted — Zahir and Faiz. They were sent to prison after an in-camera hearing; finally in 1953, a guilty verdict was pronounced.

We see literature and politics enmeshed in this story. Indeed, the same year in which Faiz was arrested saw the Pakistan government’s declaration that All Pakistan Progressive Writers’ Association is a political party.

This is not surprising, for in the manifestos of All Pakistan Progressive Writers’ Association numerous unmistakable political statements and demands were made — for example, the demand to recognise the People’s Republic of China, and the resolve to “take full part in international struggle for peace”.

But now that the association had formally lost its non-political status, and some of its major figures had been arrested, it suffered both huge organisational and literary losses. Then, in 1954, the CPP was outlawed.

Finally, in 1958, the assets of the Progressive Papers Limited that funded the CPP were sold by Pakistan’s first military dictator Ayub Khan. It was PPL that owned the newspapers Pakistan Times and Imroz. All Pakistan Progressive Writers’ Association was no longer economically viable.

In recent years both Indian and Pakistani associations of the progressive writers have been subjected to many scholarly studies. Among these, the most comprehensive and the most recent is Carlo Coppola’s Urdu Poetry 1935-1970: The Progressive Episode (published by Oxford University Press, Karachi, in 2017). This work is extensive and detailed in its narration of factual history, but one wishes it had more literary analysis in the formal sense.

Given the importance and vitality of critic Muhammad Hasan Askari’s evaluation and critique of the progressive writers, the work by Mehr Afshan Farooqi is certainly most valuable — it was published by Pelgrave Macmillan in 2012 in New York under the title Urdu Literary Culture: Vernacular Modernity in the Writing of Muhammad Hasan Askari.

The many fine English translations of Askari’s writings by Muhammed Umar Memon are indispensable in understanding Askari’s intellectual thrust.

In an indirect way, of a high value also is Kamran Asdar Ali’s Surkh Salam: Communist Politics and Class Activism in Pakistan 1947-72 (published by Oxford University Press, Karachi, in 2015). And I have personally benefitted a great deal from Shabana Mahmud’s work on Angare from which I draw some of my material here.

But how does one evaluate the literary creations of the progressive writers? There was a time when their associations embodied a galaxy of shining stars, taking into their fold practically anybody who had any claims to Urdu literature — indeed, Askari, its most bitter nemesis, was also in its fold in his early career.

It was only after the arrest of Faiz and the weakening of the All Pakistan Progressive Writers’ Association that one finds evaluative voices rising.

It is at this time that an important analytical distinction between Progressivism and Modernism – Taraqqi Pasandi and Jadidiyat – is fully articulated.

We know that two of the three pioneers of modern (jadid) Urdu poetry, Miraji and Noon Meem Rashed, did not embrace the progressive writers’ associations; Faiz being the third who did.

But all three are poets of a high order.

The three nodes of the progressive triangle I identified– pragmatism, Marxism, and a western orientation – proved to be both a boon and a bane for the Progressive Writers’ Movement. Pragmatism can suggest meaningful themes, but it often compromises creative freedom, making a work of art formulaic.

Does one not frequently feel that Faiz is at the height of his virtuosity when he is a sheer poet, unshackled, boundless? When he talks of shadows, mirrors, doors and paths, the edge of the moon, unencumbered by any immediate concern to change the society?

Compare this to the pragmatic Faiz speaking about the puss from wounds and the flesh of the worker and flinging the crowns of kings. The world of poetry prefers the unshackled Faiz.

As for the other two nodes, there is hardly a better guide for us than Askari. About the partisan criticism of All Pakistan Progressive Writers’ Association, he says, “All art is essentially healthy …

When talking about man, literature and literary criticism should at least use language that reflects the vitality and exuberance of human existence in its fullness, not economic philosophy” (as translated by Muhammed Umar Memon).

Recall that the cry “art for art’s sake” was ridiculed by the progressive writers as being ethically decadent (in a sense Faiz does the same thing in his preface to Dast-e Saba I have quoted).

Here is Askari’s corrective: “I shall vehemently deny that the concept of ‘art for art’s sake’ is an ethically decadent concept ... The concept is … not so much a disengagement from morality as it is pursuit of a new kind of morality … The final touchstone of art [is] … purely aesthetic” (as translated by Muhammed Umar Memon).

Regarding the western orientation of the progressive writers, again I have found no guide who surpasses Askari. His position has been elegantly expounded by Farooqi from whom I construct the following account.

First, Askari points out what may be called sovereignty of cultures — western writings and Urdu writings come to pass and move in two different incommensurable cosmologies, so an Urdu writer cannot emulate English or French writings.

Second, he makes an empirical observation — those progressive writers who have drawn their inspiration from western wrings have but a superficial understanding of western literature.

And finally, he examines Urdu and western languages philologically and articulates their differences, telling us, for example, that Urdu is elaborately descriptive in its temperament, lacking analytical prose, yielding only passionate narration; Urdu is not suitable for subclauses or strings of adjectives; Urdu does not admit of distances between an object and its attributes, between nouns and their adjectives.

What is the result? Even after decades of imitation, the progressive writers have failed to produce western-style prose.

“Urdu will grow only in the glow of its own tradition.”

Translation of Ghalib’s verse and Faiz’s text is by Syed Nomanul Haq

This article was originally published in the Herald's May 2017 issue with the headline "River in the drop". To read more subscribe to the Herald in print.

The writer is a professor and advisor of the social sciences and liberal arts programme at the Institute of Business Administration, Karachi.