Vehicles await passengers in front of Al-Asif Square, a jumble of matchbox apartment buildings in Sohrab Goth on the northern exit from Karachi. Buses are available here to travel to most parts of Pakistan — except to Jamshoro, a university town on the western bank of the Indus River, 150 kilometres to the northeast of Karachi.

Jamshoro-bound passengers have to take a bus going to Hyderabad. They disembark either a few kilometres short of the vehicle’s final destination, take a motorcycle rickshaw and go to Jamshoro, or they go straight to Hyderabad and then from there take a rickshaw to Jamshoro. Either way, it is an uneasy – albeit short – commute.

The rickshaws are rigged motorcycles. Their original rear part is removed and replaced by a canopied steel structure to accommodate as many as six passengers at a time. Their presence reflects the paucity of public transport as much as it highlights ingenuity.

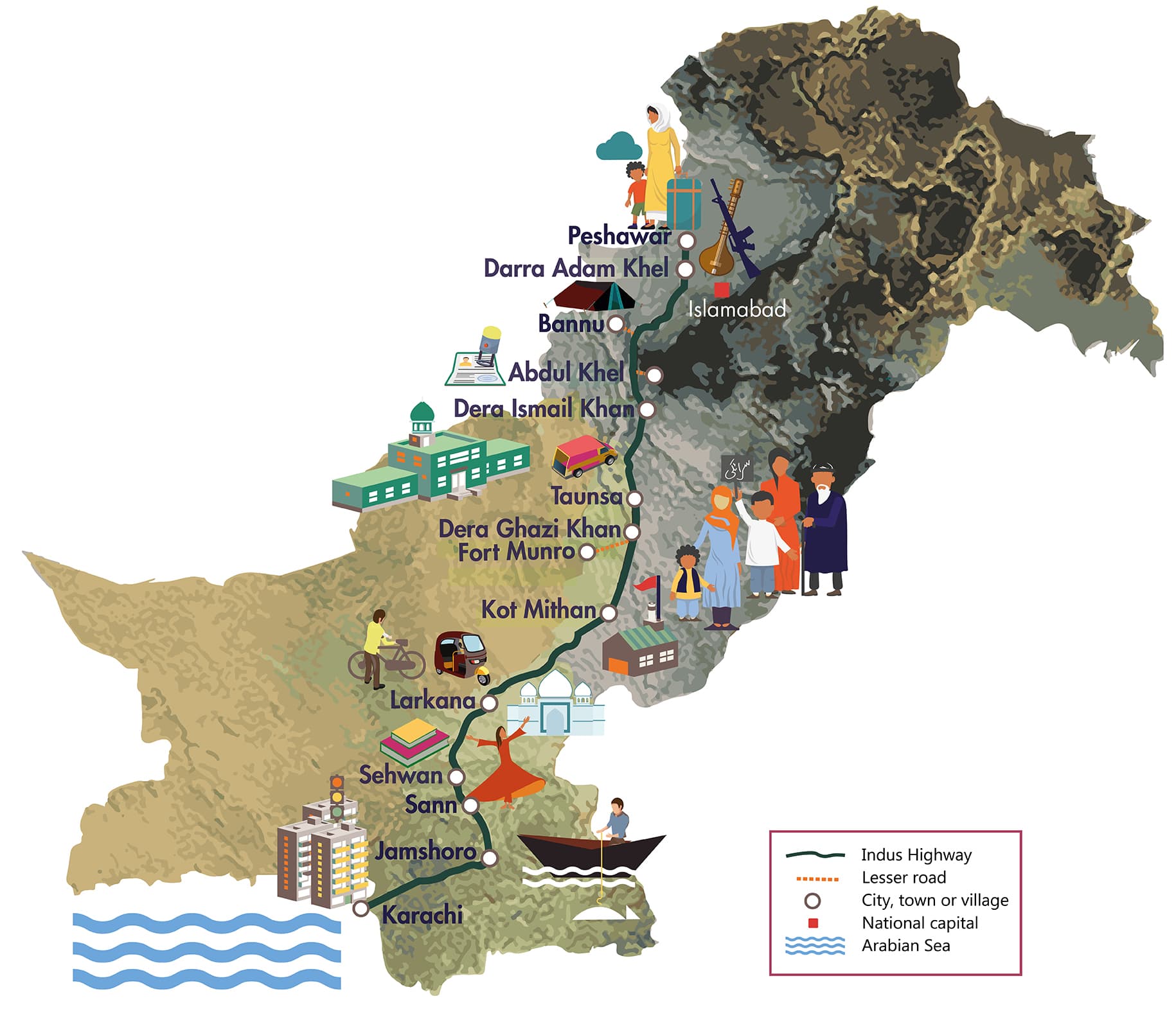

Such inventiveness is a way of life for transporters and their clients on the approximately 1,200-kilometre stretch of the road that connects Jamshoro with Peshawar. Popularly known as the Indus Highway and marked as N-55 on government maps, it was originally built in the 1970s as an alternative to the highway that links Peshawar with Karachi through Rawalpindi, Lahore, Bahawalpur, Sukkur and Hyderabad.

One rationale for its construction was commercial: cargo trucks take this road throughout the year without having to negotiate heavy passenger traffic in thickly populated urban centres — as is the case with the Peshawar-Lahore-Karachi highway.

The second reason was strategic. Running mostly along the west bank of the Indus, it is hundreds of kilometres inside the country from both eastern and western borders. The river protects it from the east and the mountains of Kirthar, Sulaiman and Hindu Kush ranges protect it from the northwest.

There were also some political considerations. The Indus Highway passes right through the geographical heart of the country. It connects some of the most marginalised parts of Pakistan — western Sindh, southwestern Punjab, southern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and the tribal areas. It also links the previously isolated parts of post-1971 Pakistan.

Roads are meant to bring disparate people and places together. The Indus Highway, it seems, has hardly done that.

The locals call it a ‘flying coach’ — a van with an original capacity to accommodate 15 people, it is restructured to make enough space for 22 passengers, seated so close to each other that none of them can bend or stretch their limbs. When it runs at high speed, it seems as if it is floating in the air because of its light weight.

A ‘flying coach’ is the only mode of public transport between Jamshoro and the small town of Sann. It stops by a tall flag, red and white, fluttering about 78 kilometres to the north of Jamshoro. The flag represents the Sindh United Party (SUP), a self-proclaimed Sindhi nationalist organisation.

A narrow asphalt road branches off the Indus Highway at the flag-post to the east and leads into Sann. The centre of the town is decorated with banners carrying the face of the late Ghulam Murtaza Shah — G M Syed to his supporters, opponents and everyone else. He is the godfather of modern-day Sindhi nationalism. His family has enjoyed a spiritual following in and around Sann for generations.

The town’s name, according to Syed’s grandson Jalal Mehmood Shah, comes from the history of local agriculture. In the olden times, he says, jute was a major crop in the area because it grows easily in flood-irrigated marshlands along the river. Jute is called patsann in Sindhi language; of the word, only Sann remains today, he says.

Agriculture, still the main source of livelihood for people in Sann, has benefitted a lot from irrigation by tube wells. Farmers here now grow all kinds of cash crops.

The old part of the town has narrow streets and brick and mortar houses. The newer part has wider avenues and bigger houses with walls and roofs made with reinforced concrete. Cows dominate empty streets in the evenings in both parts.

Riaz Mallah is a 38-year-old resident of Sann. He lives right next to the river bank and owns a small wooden motorboat that he uses to transport people to and from Sann. His passengers are mostly rural folk from the east of the river who need to be in the town for shopping, working on constructions or for getting medical treatment.

On a cold December day, Mallah is wearing a purplish shalwar kameez with a thick white jacket streaked with dirt — betraying his meagre means. A red muffler covers his head and neck to ward off the cold. Stubble frames his face — he has not shaved for a couple of days. His well-oiled black hair covers his forehead as he helps a passenger bring a motorcycle up the boat.

Mallah charges 10 rupees from each passenger for a one-way ride. The fare for transporting a motorcycle is 50 rupees. This way, he earns a few hundred rupees every day. After paying for the fuel and maintenance of the boat, he says, he makes about 4,000 rupees a month.

Mallah was once a fisherman but fishing in the Indus River is not even as productive as running the boat. The catch has dropped, he says, because most of the river water has been diverted for agriculture upstream.

Muhammad Ibrahim is a peasant in Sann. He is also a singer. Every evening, he goes to a barbershop in the town’s main bazaar for a get-together with his friends. His thick, pointed moustache, dyed black hair and Sindhi cap hide his age. The only indicator that he would be in his mid-forties is his overgrown greying stubble.

The shop is a hole in the wall. A wooden bench, two barber seats and a big mirror are crammed into its narrow, nondescript interior. Ibrahim and his friends discuss poetry, politics, religion and society here.

He sometimes bursts into a song — the same song that he sings every Thursday at Syed’s mausoleum in Sann. “Our comrade, come back to us. Our land has been taken over by the outsiders. Come back and let’s fight together and share the pain,” he sings in a plaintive voice in Sindhi. “[The song] is about struggle between the oppressed and the oppressor,” he says.

He uses the barbershop as a metaphor to explain. “A client comes to this barbershop, gets his haircut done and then pays some other barber in the market. This is how Punjab is behaving — receiving payment for the work other provinces are doing.”

Ibrahim says he does not hate the speakers of any language. He sings poetry by Punjabi Sufi poet Bulleh Shah with as much passion as he sings the poetry of Sindh’s most famous poet Shah Abdul Latif Bhitai. Punjabis, however, like to sing only in the language of power or in their own language, he argues. Ayub Umrani is another follower of Syed’s nationalist ideology.

Every workday, he takes a motorcycle rickshaw from Sann to the town of Sehwan where he teaches Sindhi literature at a government college. He has written a 26-episode play aired on Sindhi television channel Dharti TV.

It depicts two villages, one on the lower end of a river and the other on its upper end, making an obvious reference to the respective locations of Sindh and Punjab. The upstream village is powerful. It has built a canal toirrigate its fields and, in the process, has blocked the flow of water to the village downstream.

Ayub is also working on a novel on Syed’s life. He has completed the first part, which covers Syed’s life from 1906 to 1950. The second part, still being written, covers the ideologue’s life from 1950 to his death in 1995. “The novel is a true story.”

Ayub believes his novel will clear “misconceptions” about Syed’s life and politics. Syed, for instance, presented a resolution for the creation of Pakistan in the Sindh Assembly just before independence in 1947 but few, if any, people know about it, says the 51-year-old writer.

Syed’s life story is, indeed, a political rollercoaster worthy of being fictionalised. From being a proponent of Pakistan, he became a champion of what he and his followers call Sindhu Desh — an independent state consisting mostly of the present-day Sindh province.

Mixing language-based identity politics with religious and spiritual elements of Sindhi culture and couching the mixture in a socialist idiom, he founded the Jeay Sindh (long live Sindh) movement. It was not to be a political party but a campaign to raise public awareness, eventually leading to the secession of Sindh from Pakistan.

In practical terms, it did not go very far and started facing splits even in Syed’s lifetime. Today, it is divided into a wide spectrum of political organisations, none with mass appeal.

The most prominent of them is Jeay Sindh Qaumi Mahaz (JSQM), which has some support on the outskirts of Karachi as well as in Larkana and Sukkur divisions. It is further divided into more than two factions.

JSQM does not believe in electoral politics and instead, seeks to create a public uprising leading to the creation of the Sindh state. One of its splinter groups – Jeay Sindh Muttahida Mahaz – has accepted responsibility for many bomb blasts at government installations and attacks on law enforcement personnel in the province over the last few years.

On the other end of the spectrum is Jalal’s SUP. Though an offshoot of Jeay Sindh, it does not renounce parliamentary politics as Syed had ordained. SUP regularly takes part in elections.

For the public celebration of Syed’s 100th birth anniversary in Sann in 2004, Ayub wrote a play, Yaum-e-Hisab (day of reckoning). It shows a people’s court conducting summary trials of those who oppose Sindh’s independence. They are sentenced to death and are hanged publicly. “The audience was in tears as it watched the play.”

Jalal, 52, is proud of his family’s political and cultural legacy. In December last year, his neighbour Ali Haider Shah shows a visitor the personal library of Jalal’s illustrious grandfather. Located in central Sann, the library – spread over three rooms, one of them a vast hallway – is part of his family home. In the centre of the hallway lies old wooden furniture that Syed once used — a double bed, tables and chairs.

When Zulfikar Ali Bhutto put Syed under house arrest in 1972 for propagating the idea of Sindhu Desh, it was in this library that he spent most of his time, meeting visitors, reading books and making notes in his copious diaries that he had maintained since his early days in politics during the British Raj.

Jalal recalls how his grandfather hid the books so that Bhutto could not confiscate them. They were packed in steel boxes that were then dispersed in different houses in Sann. Jalal was among the few members of the family who knew which book was in which box and where that box was hidden. “Whenever G M Syed required a book, he would ask me to go and bring it.”

The books have been brought back to the library — 5,364 of them are recorded in a catalogue; another 3,000 or so are still undocumented. They are on all kinds of subjects — religion, politics, philosophy, poetry and fiction. Two dates are written on each book — the day Syed started reading it and the day he finished it.

The collection also has manuscripts and documents handwritten by Syed. “Struggle to get freedom from the empire should be one’s faith. Urdu language is the language of the empire. Make the empire your enemy, not its language. Stay connected with your roots and the people of Sindh through equality,” reads a paper he wrote in Sindhi.

Jalal does not live in his family home. He does not even live in Sann and has shifted to Jamshoro. In political terms, too, he has shifted away from his grandfather’s credo. Having sensed long ago that the space for separatism has all but vanished in Sindh, he has pivoted towards parliamentary politics.

Success, however, has eluded his party. The only time his SUP came to political limelight was in 1997-99 when Jalal became Sindh Assembly’s deputy speaker, the highest political position he has ever attained, thanks to an alliance with Punjab-dominated Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PMLN). Since then, he has lost three consecutive elections to his rivals from the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP).

Motorcycle rickshaws are lined at a bus stop on the Indus Highway. They take commuters to Sehwan which, like Sann, is a couple of kilometres to the east of the road. Rickshaw drivers scramble to get hold of passengers as they disembark from the buses. Most of them are zaireen, pilgrims, to the shrine of Lal Shahbaz Qalandar that towers above the town with its golden dome and four minarets.

The town’s lone road winds through a labyrinth of markets that remain open all through the night. Shops here sell everything — food, souvenirs and trinkets associated with Qalandar. The first floors of most of these shops are used for providing boarding and lodging to the zaireen.

A boundary wall with multiple entrances runs around Qalandar’s shrine. Policemen guard every entrance, frisking visitors before letting them in. This, however, did not stop a suicide bomber from entering the shrine on February 16 and blowing himself up amid hundreds of devotees gathered for the daily devotional dance of dhamaal. Close to 90 people died in the incident and more than 250 sustained injuries.

All life in Sehwan revolves around Qalandar and his zaireen. Drums start beating at the shrine, echoing throughout Sehwan, as evening sets in. Men and women of all religions, ethnicities and ages come together in the shrine’s courtyard – men to the west, women to the east – everyone facing Qalandar’s grave.

They point their index fingers towards the sky and start jumping and stomping the earth in a rhythm sustained by the beat of the drums and the sound of horns — this is how dhamaal is done. As the drumbeat gets faster so does the dhamaal. Some zaireen do it with such abandon that they seem to have entered a state of ecstasy — perpetually moving in circles like the whirling dervishes at Rumi’s shrine in Turkey.

Dhamaal goes on for more than 30 minutes every day, often recorded and sometimes broadcast through smartphones. People can be seen taking selfies with dhamaal dancers. Others can be spotted streaming it live to relatives back home.

Hawkers weave their way through the devotees as soon as the dhamaal comes to an end. They sell everything — from bottled water and juice to boiled eggs.

On a recent evening, a woman cries as she touches Qalandar’s grave through a steel fence meant to keep pilgrims away from the sarcophagus. She laments loudly, invoking the name of Qalandar and addressing him as one addresses one’s closest kin. She asks him to take her prayers to Allah so that her son regains his health. She stays next to the fence until she is pushed away by another devotee wanting to talk to Qalandar.

A water container, sheathed in an ornamental steel cover, hangs above one corner of the grave, just outside the fence.

Devotees call the water Qalandari paani. It drips slowly, drop by drop. Visitors put their hands below the container, catch a few drops in their palms and run their wet hands on their faces and body. The water is believed to have healing powers.

Dil Jan is happy to be back at Qalandar’s shrine. Draped in an ajrak, the 40-year-old folk musician from Sehwan is singing Dama Dam Mast Qalandar, a popular song associated with the saint. Three other musicians – including his father and 36-year-old brother Rajab Ali – accompany him. Devotees give them some change, not because they are inspired by their singing but as a tribute to Qalandar.

Jan and his companions are singing after a break of more than a month. The government put a ban on singing at the shrine after a suicide bomber attacked the shrine of Shah Noorani in Balochistan, killing at least 52 people, in November 2016. When these singers could not sing, they made do with buying groceries on credit.

Now that a suicide strike has happened at Qalandar’s own shrine, it is not clear if singers like Jan will be allowed to continue their practice here.

Ramzan Bhatti, 32, is also dependent on the shrine for his livelihood. He is among 50 photographers working in and around it. He makes about 300 rupees a day to support his family of seven.

A small point-and-shoot camera hangs around Bhatti’s neck and he holds many photo samples in his hands. A family approaches him. He gives them directions on how to stand next to the fence around the Qalandar’s grave. He tells them to raise their hands in prayer.

Then he presses the camera’s button. After snapping the shot, he goes to a stall in the backyard. Some computers and printers are placed there. He gets the photo printed and gives it to the family, charging 50 rupees. The photo shows the family as if they are praying standing right by the grave.

A small locked door is the only way to get inside the fence. It is opened only when some special guest needs to lay a wreath or a sheet of usually green or black cloth with Islamic inscriptions on the grave. Ordinary devotees push their hands through the fence to touch the sarcophagus.

They can get inside the fence if they are willing to part with some money. The door will open for those who pay a bribe of a few hundred rupees to the government employee who keeps it locked.

A man with chubby cheeks and a huge belly is busy performing another ritual near the eastern exit of the shrine. Dressed in a black kurta, he arranges a few clay lamps on a tray in front of him. He then takes out a 1000-rupee banknote from his pocket and puts it in the tray.

A devotee comes along, bows his head to the lamps and sits down. The man in black pats the devotee on the back and shouts, “Haq Qalandar”. Then, he points towards the tray. The devotee takes out some money from his pocket and puts a 100-rupee banknote next to the lamps.

Syed Wali Muhammad Shah and his family are not happy with such ‘businesses’ around the shrine. A respectable looking man in his mid-sixties, he claims he is gaddi nasheen – “occupant of the seat” – of Qalandar, just like his father and grandfather were before him. He says his grandfather Syed Gul Muhammad Shah was the custodian of the shrine when the government took control of it in 1961.

Qalandar never got married so he has no biological descendents. A number of people claim to be his gaddi nasheens. Some are the offspring of the saint’s relatives; others the heirs to his companions.

Once on a recent visit to Multan, a woman told Wali that he was not the gaddi nasheen as she knew someone else who was. “I found out later that she was referring to Azhar Shah who actually works as an electrician at the shrine.”

Being a gaddi nasheen entitles one to claim respect – and money – from Qalandar’s followers. “The more followers you will have, the more money you will get,” Wali says.

His paternal aunt, Tasneem, is a 66-year-old cancer survivor. She is the self-designated daughter of Sehwan and is involved in a number of social welfare activities in the town. She claims most of the mendicants around the shrine are fake. She also says they make more than what the gaddi nasheen does. “One of them has just bought a house worth 2.5 million rupees.”

Tasneem was visiting the shrine recently when some local children approached her for money. “I took permission from lal saeen, the Qalandar, if I could take money from him,” she says. She then took some change scattered on the sarcophagus and distributed it among the children.

As she walked out, government-appointed caretakers came running after her and told her to return the money. She said the money belonged to Qalandar so they had no right to demand its return. It was then that one of the caretakers claimed it was his money. He had scattered it on the sarcophagus to inspire the zaireen to do the same.

Her ancestral home is located behind the shrine where a street ascends to the main part of Sehwan town. Passages are narrow and crowded here and houses are mostly small, brick, mortar and mud structures.

Tasneem reminisces about her childhood when she used to play hide and seek along with her friends on the shrine’s premises. There was no fence around the grave and daily visitors to the shrine were not in the hundreds — as they are now.

There was a spiritual calm at the shrine then, she says. “Now it feels like a disco, with lights blinking everywhere. Qalandar’s spiritual influence is lost with all those lights, music and loot.”

A few blocks from Qalandar’s shrine, 55-year-old Zamir Hussain is talking to a cat. Wearing a red turban, a manifestation of his love for the lal (red) Sufi that Qalandar is known as, he wears a bead necklace with a circular metallic locket and a stone in the middle. When he finishes talking to the cat, he goes into deep thought, closing his eyes and holding his forehead with his fingers. Then he starts writing in a notebook he always carries.

Hussain is seated outside the shrine of Bodla Sikandar (one of Qalandar’s companions) and takes care of the shoes the pilgrims leave behind before entering the shrine. He picks up shoes taken off by some visitors, arranges the footwear in order, gives the visitors a piece of paper as a receipt for the shoes and goes back to his seat.

Hussain’s association with Qalandar started when he heard the song Shahbaz Karay Parwaz Te Jaanay Raaz Dilaan De, first sung by Madam Noor Jahan a few decades back. He was so moved that he instantly felt the need for a spiritual mentor. He then came across the teachings of Wasif Ali Wasif, a Sufi writer from Lahore. Hussain kept seeking guidance from Wasif for a number of years.

He was sitting at his guru’s shrine in 2016 when a woman came there and placed a garland around his neck. When he asked who she was, she said her name was Tasneem — the ‘daughter’ of Sehwan. With tears in his eyes, Hussain complained to her, “Why does Qalandar not call me to Sehwan?”

Tasneem arranged for his travel to Sehwan. Hussain left his printing and advertising business to the care of his employees and reached Qalandar’s town. He shaved off his head, beard, moustache and eyebrows and dressed himself in a long red robe.

After spending time at Qalandar’s shrine, Hussain decided to explore other shrines in the country, including that of Bhitai and those of saints buried in Makli and Uch Sharif. Back in Lahore, he kept wearing the red robe. He had not received a ‘call’ to change it.

Hussain also kept looking for an opportunity to return to Sehwan. A few months later, he found someone who was quitting his duty of guarding shoes at Bodla Sikandar’s shrine. Hussain volunteered for the position, to be able to spend 40 days in the town. “I feel in a trance throughout the day,” he says. “I respect each pilgrim, rich or poor, old or young,” Hussain adds as he touches the sole of a pilgrim and rubs his hand on his face.

On his 30th day in Sehwan, he takes a break around noon, goes to a courtyard behind the shrine and starts to read from his notebook. Visitors make a small circle around him, listening carefully. “After Qalandar accepts his seeker, he formats his hard disc and installs the software of pleasure and ecstasy,” he reads. “Pilgrimage to Qalandar’s shrine is a powerful antivirus.”

Hussain receives a call from his wife during the reading. She has arrived in Sehwan along with their three sons. He sends one of his friends to bring them to him. When his family arrives, he hugs the four of them with tears in his eyes. He introduces his cat to them and then takes them to different people around the shrine whom he has befriended. His family will stay with him for a few days.

Hussain plans to go back to Lahore after completing 40 days at the shrine. Once back home, he will resume his business. He may also publish the contents of his notebook.

No bus goes directly from Sehwan, the spiritual hub of Sindh, to Larkana, the province’s political nucleus. The passengers have to wait for a bus coming from Jamshoro, which is mostly jam-packed. A couple of agents stand on the bus stop, offering a seat at a higher-than-regular fare. The seat, however, becomes available 48 kilometres later when some passengers disembark in Dadu.

Raza Baloch is swiping through photos on his smartphone inside the bus. These were taken at a farewell dinner the previous evening at a university in Jamshoro. Wearing a dark blue suit, a light blue shirt and a matching tie, the 22-year-old looks good in them.

He is returning to his village in Larkana district after taking his final examination for a master’s degree in physics. Two of his friends accompany him. They clap and sing along as Indian film music from the 1990s plays in the bus.

When the music changes to a song by Jalal Chandio, a famous Sindhi folk singer, the three stop chatting and start listening intently. Every time the singer ends a portion of the song, they erupt into an impromptu praise. Wah wah, they say.

(He submits a freshly made CV to a private school for a teaching job as soon as he lands in Larkana. He is hired instantly to teach mathematics and physics to high school students on a monthly salary of 10,000 rupees. This is not what a person holding a master’s degree should earn, he says.)

Larkana is the home district of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, founder of the PPP, Sindh’s ruling party, which should have created better livelihood options here. But the area has experienced next to no industrialisation since 1967 when the party was founded. The district remains a largely agricultural zone.

Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s white marble mausoleum, in Garhi Khuda Bakhsh village about 23 kilometres northeast of Larkana city, is visible from afar. A narrow road leads to it, passing through wheat fields and small clusters of human abodes that appear to have come straight out of the pages of a book on Mohenjodaro, the oldest human settlement in this part of the world.

The mausoleum houses the graves of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto (hanged by the state), his son Mir Murtaza Bhutto (killed by the police) and his daughter Benazir Bhutto (assassinated by Taliban militants in a gun and bomb attack). A helipad marks the entrance to a huge open space to one side of the mausoleum. To one side of that space is a bomb-proof raised platform.

Whenever Asif Ali Zardari, former president of Pakistan and the co-head of the PPP, and his son, Bilawal Bhutto Zardari, land here to address the party cadres and voters, they use the secured platform as a stage. They also make speeches from behind a bullet-proof glass screen. Security in Sindh remains precarious under the party’s watch.

Inayat Hussain Umrani is sitting with another party’s workers inside Al-Murtaza, the ancestral home of the Bhuttos in Larkana. They hold a similar gathering every week. They represent PPP-Shaheed Bhutto, a breakaway faction founded by Mir Murtaza Bhutto before he was slain by policemen in 1996 near his home in Clifton, Karachi.

“We do not want to be a party of feudal lords. We have party workers from the middle class,” says Inayat as he complains that the bigger PPP has become a party of feudal lords who cannot care less about ordinary people. It was only under Zulfikar Ali Bhutto that development projects were carried out in Larkana, he says. “A lot of corruption has been done in the name of Bhutto.”

Inayat points to a recent newspaper column written by Amar Jalil, a noted Sindhi intellectual. In the column, Jalil writes of an imaginary visit to the Bhutto mausoleum: people gathered in Garhi Khuda Bakhsh are beaten up by the police as Zardari arrives there; as Jalil takes flight to avoid the beating, he bumps into an old man also running away; he is no other than Zulfikar Ali Bhutto himself.

Zardari delivers his address at the mausoleum from a bullet-proof, bomb-proof stage, reiterates Inayat. He comes from above and goes back above. “How can he interact with the people?”

Abdul Razak Soomro is a founding member of the PPP. He claims whatever development is there in the area is because of the Bhuttos and their party. At the time of Partition, there were only three high schools in Larkana, he says. “There was no college in Larkana district. When Zulfikar Ali Bhutto came into power, he started providing roads, dispensaries and a medical college to the city. Thousands of villages and towns got electricity [after Benazir Bhutto became prime minister twice in the 1990s].”

Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, indeed, brought the rural backwaters of Larkana to the political centre stage. The place became synonymous with his tendency to concentrate all powers in his own hands. He appointed his cousin Mumtaz Bhutto, another native of Larkana, first as the governor of Sindh and then as the province’s chief minister. Al-Murtaza became the most sought-after political rendezvous for politicians trying to curry favour with Zulfikar Ali Bhutto.

Rebel poet Habib Jalib satirised all that in a memorable verse: “Larkanay chalo varna thanay chalo” (Move to Larkana, otherwise you’ll be taken to a police station).

Soomro, 89, divides his time between Larkana and Islamabad where he works as a Supreme Court lawyer. He was appointed by the PPP regimes as Pakistan’s ambassador to Oman (1989-90) and to the United Arab Emirates (1994-96). Walls in his drawing room are adorned with framed photographs — many of them show Soomro and Zulfikar Ali Bhutto together.

Since the departure of the Bhuttos from the political scene, Larkana has lost its political significance. The centre of PPP’s power has shifted elsewhere — to Bilawal House in Karachi’s Clifton area.

Neglected and overlooked, Larkana is disappearing behind layers of dust, looking more and more like Mohenjodaro, the city of the dead.

No bus links exist between Sindh and Punjab on the Indus Highway. Anyone who requires travelling from Larkana in the former province to Kot Mithan in the latter, will need to change multiple vehicles on the nearly 300-kilometre journey: take a passenger van from Larkana to go to Kandhkot — distance 137 kilometres; take another van to travel to Kashmore at the border of the two provinces — distance 50 kilometres; wait at a border checkpoint for a bus coming from Karachi and going to Peshawar, hop onto it to travel to Kot Mithan bus stop on the Indus Highway standing in the aisle throughout the way — distance 100 kilometres; take a motorcycle rickshaw to reach Kot Mithan — distance 6.3 kilometres.

Kot Mithan is the home town of Khawaja Ghulam Farid, a 19th century Sufi poet who is also buried here. His collection of poetry, Diwan-e-Farid, was first published in 1882. An entire branch of literary studies – Faridiyat – has evolved in the 20th century to study his life, time and works.

Mujahid Jatoi claims to be an expert in Faridiyat. “Farid and the struggle for Seraiki [identity] are in my blood. You cannot separate the two,” he says. He sports a flowing white beard and his slicked-back hair is tied in a small ponytail. He wears a green cap made of cloth (just like the one Farid wore) and a colourful cotton shawl, known as Faridi chador, is draped around his neck. Mujahid is a native of Khanpur, a town in Rahim Yar Khan district, about 50 kilometres to the east of Kot Mithan and on the other side of the Indus River. But his love for Farid is so intense that he spends most of his time in Kot Mithan.

At 3 am on a chilly morning in December last year, when the temperature outside has dropped to 10 degrees centigrade, Mujahid is sleeping inside a guest room at Farid House, reserved for devotees requiring to stay overnight, in central Kot Mithan. His cell phone suddenly rings. He speaks to the person on the other side, giving him directions on how to reach Farid House.

The man he is talking to is 54-year-old Munawar Iqbal Hussain, an MPhil student at the University of Lahore’s campus in Pakpattan. He is visiting Kot Mithan as part of research for his thesis — a comparative analysis of three Urdu translations of Farid’s writings. One of the translations is compiled by Mujahid.

Munawar reaches Farid House at 5 am. Mujahid vacates the bed for him and goes to sleep on a wooden sofa next to the bed. Munawar will stay in town for six days, spending most of his time studying at Farid’s museum and library, managed by the Khawaja Farid Foundation. Mujahid happens to be a director of these establishments.

After Munawar is sufficiently rested, he is taken to the Indus for a walk. At the bank of the river, right where the agricultural fields end, two abandoned boats are parked — one of them is named Indus Queen.

The other was used during the 19th century for transporting goods between Karachi and Multan.

Indus Queen became a private property of the Nawab of Bahawalpur after the British left the Indian subcontinent in 1947. When the state of Bahawalpur was abolished in 1955, the boat was given to the Government of Pakistan.

It was used by residents of the area to cross the Indus between Kot Mithan and Chachran Sharif — both places figuring prominently in Farid’s spiritual and poetic quest.

Today, the boats are rusting amid sandy dunes on the river bank. Next to them is a makeshift floating bridge. It is the only way to cross the river here. The nearest available permanent bridge is 130 kilometres upstream in Dera Ghazi Khan — or 108 kilometres downstream in Kashmore.

Mujahid remembers travelling on the boat. On board, musicians would sing Farid’s poetry, which celebrates deserts, forests and waterways of his native region, to the delight of the passengers. Mujahid then uses the boat as an analogy to explain how Punjab has treated what he calls “occupied Seraikistan”: everything has been taken from locals and is then left to rot.

Mujahid was 11 in 1962 when his father Murid Hussain Jatoi took part in a conference in Multan. It was at that conference that the participants decided that the language spoken by the majority of the residents in southern and southwestern Punjab would be called Seraiki — all other localised names such as Multani, Riyasti (spoken in the former state of Bahawalpur) and Deraywali (used in Dera Ghazi Khan and Dera Ismail Khan) would cease to exist. The conference also came up with maps of the proposed Seraiki province.

The “biggest atrocity against the Seraiki people”, Mujahid says, “was committed when our land was merged with Punjab” after One Unit (that brought together the four provinces of West Pakistan into a single administrative and political entity) was abolished in 1970. The move resulted in public protests.

A young Mujahid saw his father taken to jail due to his participation in the protests. That is when the activist in him was born. He subsequently became one of the founders of Seraiki Qaumi Movement, a small political organisation.

“It is an insult when our region is called south Punjab. [It is] not a part of Punjab. I am not Punjabi. Why can’t you call me a Seraiki instead,” he says angrily. “Why are you afraid of my identity? Why can’t I call myself what I am?”

He concludes his harangue by calling Pakistan a four-wheel vehicle that has three wheels of a car but the fourth one of a truck. That bigger wheel to him is Punjab. “We, the people [of Seraiki areas] are a labour colony of Lahore.”

Paritewala, a village 40 kilometres to the north of Taunsa town, is the birthplace of Dr Muhammad Ahsan Wagha. He is a linguist and former broadcaster who wrote his doctoral thesis, The Development of Siraiki Language in Pakistan, at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London in 1997. It examines the evolution of Seraiki language with reference to an ethno-national movement for Seraiki identity.

“The Seraiki movement has a centre but it lacks a circle,” says the tall, clean-shaven Wagha who is in his late sixties and lives and works in Islamabad. A Seraiki geographical entity does not exist on the map of Pakistan, he explains.

Wagha says the Seraiki movement started with the construction of irrigation canals at the beginning of the 20th century. This was closely followed by massive settlement of Punjabi peasants in areas that constitute the southwestern and southern parts of Punjab today.

The same process continued after Partition. It was, in fact, expedited with the arrival of Muslim migrants from East Punjab who were allotted businesses, properties and lands left behind by Hindus and Sikhs who migrated to India in 1947.

Fears soon emerged that Punjabi dominance of agriculture, industry, politics and military power may result in the disappearance of culture, customs and the language that existed in southwestern and southern Punjab before the arrival of the Punjabis. Seraiki language was seen as a tool to resist that trend. It became instrumental in developing an ethno-national consciousness in the 1960s, Wagha says.

Ashiq Buzdar is one of the leading champions of that consciousness. Sitting on a charpoy made of palm leaves on a sunny winter morning in Mehraywala village in Rajanpur district, he holds a newspaper in his wrinkled shaking hands.

With his thick, untrimmed white moustache and white and uncombed long hair, he looks like a stereotypical poet. His wrinkled clothes and unpolished black shoes show that life has been unkind to him. For the last 18 years or so, he has had no stable source of income.

A friend once asked Buzdar how old he was. “I am as old as Pakistan” — born on August 14, 1947. Then the friend inquired about his health. “My health is just like Pakistan’s. I am crippled; I have pain in my knees; it is difficult for me to even walk.”

When Buzdar was hospitalised recently, he applied for free treatment. A doctor came to investigate his plea and asked him about his profession. “My profession is written within my name. I am Buzdar.” Buz in Persian means goat and dar in the same language means keeper.

“I am a shepherd,” he said. “How low can you go? Just to get [free treatment], you have become a shepherd,” the doctor commented. Buzdar replied with a verse by Allama Iqbal: Agar koi shoaib aye muyassar, shabani se kaleemi dou qadam hai (If one gets the right guide, talking to God is only a couple of steps away from being a shepherd).

Buzdar’s poetry revolves around his native land and the struggles of its people. His books were banned during the military dictatorship of Ziaul Haq. One of his poems from those days is titled Court Martial.

It talks of two Seraiki-speaking Hindu soldiers who migrated to India in 1947. During a Pakistan-India war, they caught a Muslim soldier from Pakistan. When they asked him where he was from, he said he was from Dajal (a small town to the west of Rajanpur).

Hindu soldiers had also migrated to India from Dajal. They started crying and asked their prisoner how their motherland was, how its festivals and food were. They asked him about Farid’s shrine and his songs. Then they let him go.

Next day, when the Pakistan Army opened fire on the Indian post, the soldier refused to participate, fearing that his bullets might kill the soldiers from his motherland. “How will I go back to my land after spilling the blood of its sons,” he said. He threw his weapon away and presented himself for a court martial.

Buzdar’s other famous poem is titled Qaidi Takht Lahore De (Prisoners of the Throne of Lahore). It was also banned in 1985. Since then, it has become an emblem of Seraiki politics and a much-used symbol to criticise Lahore’s pre-eminence in Pakistan’s political, economic and administrative structures.

Buzdar and some other Seraiki activists, poets and intellectuals got together in the mid-1980s and formed a non-political organisation called Seraiki Lok Sanjh or Saraiki Peoples’ Association. “ … we have embarked on a journey through sizzling sand. Only those willing to let their feet burn will join this caravan,” is how Wagha explains the founding ethos of the organisation.

Buzdar has been arranging an annual Seraiki festival for the past 31 years in his native village of Mehraywala. The objective of the festival is to unite the residents of the Seraiki-speaking region and celebrate Seraiki identity.

Demand for creating a separate Seraiki province is one of the most recurring themes at the festival. Senior PPP leader Yousaf Raza Gillani attended the festival some years ago (before he became the prime minister in 2008), as have many other prominent politicians in the region.

Attendees also include Sindhi nationalists — such as Rasool Bakhsh Palijo who leads a linguistic, cultural movement called Qaumi Awami Tehreek. (His son Ayaz Latif Palijo has taken part in elections from the platform of his Awami Tehreek with no success.) “Our enemy is the same — Punjab,” Buzdar says.

Around 60 motorcycle taxis are parked in Kot Mithan’s main bazaar. They charge 100 rupees each for taking passengers to Rajanpur. Those who wish to travel to Dera Ghazi Khan from there onwards can hop on to an 11-seat van that departs every hour.

Dera Ghazi Khan is located on the confluence of the Indus Highway and the N-70 that comes from Multan in Punjab and goes on to Qila Saifullah in northeast Balochistan. The district marks the geographical centre of Pakistan — most of Punjab (of which it is a part) to the east; Sindh to the south; Balochistan to the west and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa to the north. Unsurprisingly, trucks and their crew from every part of the country can be spotted here.

Mushtaq Gaadi, a teacher at the National Institute of Pakistan Studies at the Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, believes Dera Ghazi Khan could have been an ideal location for Pakistan’s capital. “Now only Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Punjab have easy and ready access to the capital in Islamabad.

If Dera Ghazi Khan was the capital, people from all provinces would have equal access to it.” This, in turn, would have had positive impacts elsewhere. “There would have been no division between south and north within Punjab,” says Gaadi.

As of now, geography is more a bane than a boon for Dera Ghazi Khan. It gives the city, and by extension the district, all the problems combined that exist in different parts of the country — poverty and marginalisation of the Baloch (who form a large part of its population); linguistic and ethnic politics of Sindh; religious militancy of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and low-quality urban growth of Punjab.

Its main bazaar is crowded – with pushcart vendors selling all kinds of wares from clothes and electronic equipment to vegetables and fruits – and in need of an urgent clean-up. Roads and streets here are dilapidated, even though they criss-cross the city in and from every direction. Colourful but noisy motorcycle rickshaws are lined up everywhere.

Other than low-level commercial activities in the city (and agriculture and livestock rearing in the rural areas), there are next to no job opportunities in Dera Ghazi Khan. Yet, Hafiz Abdul Kareem has prospered here, both financially and politically.

A member of the National Assembly from Dera Ghazi Khan city, he has been running a large mosque and madrasa since 1986. He has been active in electoral politics since 2008 when he almost defeated Sardar Farooq Ahmed Khan Leghari, one of the strongest Baloch tribal chieftains in Dera Ghazi Khan who worked as a federal minister before becoming the president of the country in 1993.

Kareem is associated with Jamiat Ahle Hadith Pakistan, a salafi group affiliated with PMLN. He owns many businesses in Dera Ghazi Khan – a petrol station, a restaurant, a shopping plaza and a housing colony – as well as some in Multan.

Opposite his madrasa, which is protected by private armed guards, is a two-storey building where his family lives. His son, Osama, points to a big stock of firewood just outside the house. This is used for fueling cooking stoves and heaters inside the house as well as in the mosque and the madrasa.

“There is no natural gas in the area,” says Osama, “not even at [our] house.” One of the main natural gas pipelines that links central Punjab with gas fields in Sui, Balochistan has been passing not far from the city for decades.

Pointing to the performance of the PMLN’s Punjab government, Osama says in Seraiki: “Demokaresi kujh na karesi” (Democracy means doing nothing).

Sanaullah, 24, holds a bachelor’s degree in applied geology from the University of Azad Jammu and Kashmir and gives tuitions in Sakhi Sarwar town, about 33 kilometres to the west of Dera Ghazi Khan. He teaches mathematics and other science subjects to three students, charging each of them a monthly fee of 200 rupees for each subject. He makes about 2,400 rupees every month.

Sanaullah is the first graduate in his Baloch tribe of about 10,000 people. His native village, Rakhi Gaaj, is located within the dry, brown mountains of Sulaiman range, more than 60 kilometres to the west of Dera Ghazi Khan.

It has no electricity, no healthcare facilities, no running water. It has only one primary school but its lone teacher never shows up. Local women walk many kilometres every day to get water from mountain streams.

When Sanaullah graduated in June 2016, he heard about a Japanese firm building steel bridges in the mountains on the road that links Dera Ghazi Khan with Quetta. He thought he could get a job in the project. But then he was informed that all the jobs were already taken — mostly by people from central Punjab. “Even vegetables and rental cars come from Punjab. Why are locals not given any priority [in jobs],” he asks.

Sakhi Sarwar town’s only link with Dera Ghazi Khan is a narrow potholed road. Stone crushers work ceaselessly on both sides of it, preparing raw material for roads being built elsewhere. The dust rising from crushing plants envelops everything along the road, reducing visibility even during the day. Within the town, not a single street is paved.

A British-era fort towers above a mountain, about 50 kilometres to the west of Sakhi Sarwar. Overlooking the border between Punjab and Balochistan from an altitude of around 1,900 metres, it is one of the highest and coolest places in the entire Sulaiman range.

Named after Colonel Munro, Dera Ghazi Khan’s commissioner at the time, Fort Munro was used as a hill resort by the British. Since then, the place has developed into a small town.

The road to Fort Munro is steep and turns at sharp angles. As the altitude increases, the temperature starts dropping dramatically. The road passes through multiple checkpoints, manned by the Border Military Police, before it takes a turn towards the left, just before the provincial boundary and ascends into town.

The entrance to Fort Munro is dominated by colourful billboards carrying the names and contact information of local hotels and guest houses. In late December 2016, there are no tourists around. Only four local men can be spotted in the main bazaar.

They are lazing around under the warm sun, discussing local politics in their native Balochi language. The rest of the place seems abandoned. All shops, except one, are closed and not a single individual is visible on the streets.

Saleh Leghari, who owns the lone open shop, is one of the four men. He says most of the residents of the town have migrated to either Dera Ghazi Khan or Multan to avoid the cold weather. Temperature here drops below freezing at night and there is no electricity available for days on end. Only 12 or so families are still here, he says.

When the weather is pleasant – during the summers – Fort Munro attracts many tourists from southern Punjab and northern Sindh. “Our hill station is not inferior to Murree but life there goes on because Murree has basic facilities, including water and natural gas, throughout the year,” says Saleh.

Local women travel many kilometres to a stream to fetch water. People also pay a local supplier who sells water from a tanker at asking price. Saleh says he pays 1,200 rupees for water that lasts two weeks.

His friend, 40-year-old Sona Leghari, is full of complaints about the lack of healthcare in Fort Munro. “I suffered a back spasm and went to the town’s only hospital. There was no doctor there.” He had to seek help from a relative to travel to Rakhni, a village in Balochistan about 22 kilometres to the west of Fort Munro, on the backseat of a motorcycle to seek treatment.

“People say Punjab is the most developed province in Pakistan and we say we are the least developed area in the entire country,” says Saleh.

Taunsa is a large town about 83 kilometres to the north of Dera Ghazi Khan. It is the last resting place of Khawaja Muhammad Suleman Taunsvi, a 19th century Sufi saint who came here from Loralai in Balochistan. His descendents actively participate in the area’s politics. They regularly contest elections, sometimes against each other and at other times against the chiefs of the local Baloch tribes.

A major feature of the town is its long history of anti-Shia activism. One of the first and foremost exponents of the movement to declare Shias infidels was one Abdul Sattar Taunsvi, a local sectarian firebrand.

Starting in the 1960s, he developed a large following across Punjab. When he died in 2012, tens of thousands of people attended his funeral.

A narrow street in central Taunsa leads to a mosque and madrasa he built in 1967 under the banner of Tanzeem Ahle Sunnat Wal Jamaat, a precursor of many anti-Shia organisations, including Sipah-e-Sahaba Pakistan and Lashkar-e-Jhangvi.

Around 90 students from the surrounding Seraiki-speaking area are studying here as resident scholars. “Our graduates go to different parts of the country to teach in madrasas and as prayer leaders,” says Abdul Samad Taunsvi, the madrasa’s administrator.

Over the last decade or so, a number of anti-Shia terrorist attacks have taken place in and around Dera Ghazi Khan. Some Sufi shrines in the area have also seen suicide blasts and bomb explosions — most prominent among them being the shrine of 12th century Sufi, Syed Ahmad Sultan, in Sakhi Sarwar town.

The shrine attracts thousands of devotees from across Pakistan throughout the year. In the late 2000s, fliers appeared in the town, one of them pasted on the shrine’s entrance, saying that many rituals practised here – dhamaal, beating of drums and self-flagellation (a Shia practice signifying mourning) – were un-Islamic and needed to be stopped forthwith. Otherwise, the fliers warned, there would be consequences.

Two blasts hit the shrine on April 3, 2011, taking 52 lives and injuring 172 people. The victims included many women and children.

The Indus Highway enters Khyber Pakhtunkhwa’s Dera Ismail Khan district about 70 kilometres north of Taunsa. A commuter unfamiliar with the local administrative geography will not notice when they have left one province and entered the other. Even the language remains the same — Seraiki. A large number of people travel on a daily basis between Taunsa and Dera Ismail Khan.

It is in Dera Ismail Khan city that the transition from Seraiki to Pashto starts becoming visible. In local markets, people can be heard speaking both languages.

Syed Hafizullah Gilani lives on the outskirts of Dera Ismail Khan with his wife, a son and two daughters. He is the author of six books, all written in Seraiki and Urdu. He has also been writing plays for Radio Pakistan since 2007.

Hafizullah is frustrated over the way Radio Pakistan, the state-run broadcaster, treats his writings. “How would you feel if your legs and hands were tied and then you are thrown into a river and asked to swim? How would you be able to swim?”

One of the characters in a skit he wrote was not allowed to utter the word Panama because Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif is “sensitive” about it. “My thoughts are not what my words are.”

Hafizullah, 56, is also the author of a critically acclaimed novel written in Seraiki. It is an extended metaphor for the deprivation of Seraiki-speaking people and narrates the tale of a Seraiki widow who is desperate to feed her children but is exploited by a prayer leader.

He conducted extensive research before naming the prayer leader. He wanted to avoid using the name of some real-life person. “Otherwise I would be in trouble.”

Hafizullah has been working for years to open a Seraiki language and literature department at Dera Ismail Khan’s Gomal University. In 2012, the university authorities laid the foundation stone of the department’s building but construction has not begun. “Now we are told that there are no funds to open the department,” he says.

The biggest hurdle, according to him, is Maulana Fazlur Rehman, head of Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam-Fazl (JUIF) and chairman of the parliament’s Kashmir committee. “The department will not be opened as long as there is Maulana in Dera Ismail Khan,” says Hafizullah. “His mother language is Pashto, not Seraiki, and he has conservative views [whereas] Seraiki literature is secular in nature.”

Rehman lives about eight kilometres north of Dera Ismail Khan city. A mosque with multiple domes stands in front of his bungalow, located along the Indus Highway.

A barbed wire fence sits atop the mosque’s boundary wall. Many JUIF flags – black and white stripes – and the party’s slogans are painted on the wall. One of them reads: “The message from the Ummah is that [it wants] the system of God.” The entrance to the mosque is guarded by police.

Next to the mosque is a madrasa built in the late 1990s. In one of its rooms, full of religious books, is a three-dimensional model of a two-storey building. This is how the madrasa was originally supposed to look but the plan was abandoned to avoid creating security threats to Rehman’s residence.

The madrasa was built with funding from Muammar Gaddafi’s Libyan government. Libya’s ambassador to Pakistan at the time was one of the chief guests at its opening. It provides religious studies to 260 students — all, except 30 of them, are resident scholars.

About 65 kilometres to the north of Dera Ismail Khan city, a road branches off from the Indus Highway and turns towards the east. It leads to the small village of Abdul Khel, the burial place of Rehman’s father, Mufti Mahmud, who was a pioneer of the Deobandi branch of Sunni Islam in these parts.

Mahmud briefly served as chief minister of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in the 1970s, heading a right-left coalition that also included the National Awami Party, a conglomerate of Baloch and Pakhtun nationalists.

He resigned as chief minister in protest against the sacking of Balochistan’s provincial government by Zulfikar Ali Bhutto in February 1973. He later headed the opposition movement – known as Pakistan National Alliance – that led to Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s ouster from power in 1977.

The village is sandwiched between two mountains — Koh Ratta (The Red Mountain) and Koh Neela (The Blue Mountain). A narrow street that turns into a sandy path passes through the village, leading all the way to a mosque built by Mahmud, who is buried in a graveyard next to it.

Right at the entrance of Abdul Khel is the camp of a construction company. It is building part of a road that connects Grand Trunk Road with Quetta through Zhob and constitutes the western route of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). The road will pass right through Rehman’s village.

Ashfaq (not his real name) is an MPhil student at Gomal University. He regularly participates in an annual congregation of Muslim missionaries in Raiwind, near Lahore, and calls Rehman his uncle because of some familial ties. Growing up, the 34-year-old seldom saw his father — who is always travelling with the missionaries of the Tableeghi Jamaat.

On a day in late December 2016, Ashfaq is standing with his friends inside the university, talking about jihad. He is wearing a long, plain kurta with an ankle-length shalwar. His head and shoulders are covered with a black and white keffiyeh. Putting his bag and diary to his side, he says he is ready to leave for jihad right away but his mother does not let him.

He has been to jihad before when Dera Ismail Khan became a major recruitment ground in early 2000s for those willing to fight in Afghanistan against the American-led forces that had invaded the country in the wake of the 9/11 terror attacks in New York. “I was inspired by one of the rallies [led by Rehman] to fight against the infidels,” he says.

Ashfaq went to Kabul in 2002 with a group of militants without informing his family. “It was like being in heaven. There were guns everywhere,” he says. Conditions were harsh, he acknowledges, but “to kill as many Americans as we could” was a strong motivation. “I stayed there for four months and went through a strong military training under Taliban commanders.”

But his mother was distraught. She used her family connections with Rehman and called back her son from Afghanistan. “I was forced to come home. The commander tied [my arms and legs], threw me in a car and brought me home,” says Ashfaq.

He experienced serious depression when he saw people in Pakistan going through their daily business as usual – going to college, listening to music, women roaming freely in bazaars – when their Afghan brethren were fighting the Americans.

He often talks about what he experienced while he was in Afghanistan. I felt being at peace by killing the infidels, he says. “My dream is to die as a martyr while fighting the infidels.”

On January 4 this year, the Indus Highway was blocked. A remote-controlled bomb had targeted a police van on the road, injuring 15 people, including five police officials. All vehicles traveling from Dera Ismail Khan to Bannu were being diverted to another route.

Bannu city, 108 kilometres to the north of Dera Ismail Khan and 62 kilometres to the west of the Indus Highway, is home to thousands of internally displaced persons (IDPs) from the tribal areas.

Tahir Dawar, a barrel-chested young man of 33, is one of them. His round face, trimmed black beard, thick curly hair and narrow almond eyes betray his Pakhtun identity even in a cursory glance. He runs a small medical laboratory in Bannu city.

Dawar is originally from Miranshah, headquarters of North Waziristan agency, 70 kilometres to the west of Bannu. He is doing an MPhil from the Allama Iqbal Open University in language and communication. Dawar is also a poet.

He believes the ongoing military operation against Taliban militants in North Waziristan is the biggest tragedy to befall the people of the agency after the imposition of the Frontier Crimes Regulation by British authorities in the early 20th century. He used to organise poetry recitals, mushairas, in his native area before the start of Operation Zarb-e-Azb in 2014, he claims.

His entire tribe relocated to Bannu and its surrounding areas after the operation began. Since then, they have been living as IDPs in government-run camps and rented accommodations. Dawar used to own 25 shops in Miranshah bazaar. The “bazaar is no more” — it was demolished by the military.

On January 1, 2017, Dawar is reading newspaper reports about New Year celebrations across the world. He complains the change in the calendar has brought no change in the situation in North Waziristan.

Last year, at the end of the fasting month of Ramzan, he went to Baka Khel camp for the IDPs on the outskirts of Bannu. He was so depressed to hear the plight of the people there that he instantly wrote some verses. “I do not have a house. Neither a village nor a neighbourhood … What do I do with this morning, afternoon and evening? … I live in a tent. How am I to celebrate Eid?”

Dawar says he has not registered himself as an IDP. The registration requires the acquisition of a special identity paper – a Watan Card – which the government issues after a government-appointed tribal elder, or malik, verifies that the applicant for the card is loyal to the state.

A malik receives a monthly salary from the federal government under the provisions of the FCR that also makes him responsible for all the acts of omission and commission of his tribespeople. The malik that Dawar needs to get verification from is uneducated. “How can an uneducated person verify the identity of an educated person,” he asks.

Ghulam Khan Wazir, 43, is a tribal malik from North Waziristan. A burly man with a thick moustache and round face, he lives in Bannu, as do most of the members of his 30,000-strong Madakhel tribe. Their native area in Datta Khel tehsil of the tribal agency is right on the border between Pakistan and Afghanistan.

“When Operation Zarb-e-Azab started, my entire tribe had to migrate overnight,” he says. Around 14,000 of them went to Khost in Afghanistan. Others moved to different parts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

Those who went to Afghanistan took all their belongings – vehicles, livestock, etc – with them. Now that the border between the two countries is sealed in North Waziristan, Wazir says, “it is getting difficult” for them “to come back from Afghanistan”.

Those who are in Pakistan have other problems to tackle.

Bannu Township is a newly built housing facility 10 kilometres northeast of Bannu city. It is a well-planned neighbourhood with asphalt roads, a central library and two-storey houses. North Waziristan’s highest civilian officer, the political agent, has an office in a rented house at the far end of the township. A typist is sitting outside the office’s boundary wall.

He types and prints applications for IDPs for the issuance of Watan Cards and for other government-provided services, such as rations and monthly stipends. Men of all ages are standing inside the courtyard of the office — not in a queue but in a rambling arrangement. They are all waiting for a tiny entrance to open.

The political agent, a tehsildar and three clerks are sitting inside the building — having their lunch of pulao. The men outside keep knocking at the entrance; the men inside keep ignoring them, engrossed in their meal.

As Wazir walks into the courtyard, IDPs flock to him with their demands. He has already signed their documents. Now they need the signatures of tehsildar Muhammad Rafiq. Wazir cannot offer them any help.

He is carrying a folio with him. It contains documents pertaining to the case of one Bada Gul who has been in jail in Saudi Arabia for the last six months. Officials in Pakistan’s embassy in Saudi Arabia have called Wazir to verify if Bada Gul is a Pakistani citizen.

Wazir has collected and signed all documents to prove just that but tehsildar Rafiq is still reluctant to issue a character certificate for Bada Gul. “If the tehsildar does not sign the character certificate, Bada Gul will spend the rest of his life in jail in Saudi Arabia,” Wazir says. He then enters the buildings and gets into a fight with Rafiq.

This is not the only case of official apathy, Wazir says. Every time he comes here, he feels “humiliated”. He says the political agent and tehsildar are not from North Waziristan and do not understand the tribal culture. “They just exploit the tribesmen and create trouble for them.”

Wazir is also the general secretary of a committee of those displaced by military operations. Many of them, he says, are staying in unofficial camps – mostly along the Bannu-Kohat road – without any official assistance and surviving on rations provided by the World Food Programme.

Shelters at these camps are basic — blue canvas sheets pulled over walls made from dried reed. “It gets really cold at night here in winters,” says Razmat Khan, 45. His family of eight siblings and five children is among 25 or so families living in an unofficial camp. “There is no school in or around the camp. My children are deprived of education,” he says. A more urgent problem is that the camp has no running water and no sanitation.

Muhammad Fawad, assistant commissioner of Bannu, agrees that 8,000 or so IDPs are not registered with the government and are living in unofficial camps. Bannu has only one official IDP camp — in Baka Khel. The camp, according to him, houses 450 families. The total number of registered IDPs in the district is 17,000, he adds.

When the operation started, he says, “we did not have the capacity” to take care of all IDPs. The IDP influx “brought a sudden increase in the population of Bannu and put an increased burden on the provincial government”.

Gunshots echo in the mountains, shot after shot, a little ways away from the Indus Highway. This goes on for a whole day as arms manufacturers and arms traders test their newly-made weapons. This is the tribal area of Darra Adam Khel – about 35 kilometres to the south of Peshawar – known for its arms manufacturing that dates back to the early British period.

All kind of guns are on display in Bismillah Jan’s small shop in Bakht Zaman Plaza, located in Darra’s main bazaar. These are all made by him. There is an AK-47 Kalashnikov, a 12-gauge gun, a pistol and much more. Every shopkeeper in the plaza has a display centre on the ground floor and a small factory on the first floor. There are 70 such establishments in the building.

Bismillah Jan is working on a new gun. He has downloaded its design from the internet. “I only saw the photograph of the gun made in Germany. Now I am making an exact copy of it,” he says. Once he finishes his job, he claims, no one will be able to differentiate between the original and the copy.

This skill at copying proved a big boon for local arms manufacturers in the late 1980s. At the end of the war in Afghanistan against the Soviet Union, the Americans announced they would buy back weapons from the Afghan mujahideen.

Factories in Darra worked overtime to manufacture copies of the sophisticated American and European arms the mujahideen had. These copies were smuggled to Afghanistan in thousands where the Americans paid in dollars to get hold of them. That way the mujahideen got to keep their weapons and also made a lot of money.

The same process was repeated, after 2001, when the Americans offered Taliban fighters money in exchange for surrendering their weapons.

Arms manufacturing runs in Bismillah’s family, though he does not know when and how it started. His father did it, his grandfather did it and so did his great-grandfather. The business witnessed its first boom during the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in the late 1970s. Thousands of arms were supplied from here to the mujahideen trained by the Pakistani military and funded by the United States and Saudi Arabia.

“That was a glorious time,” says 40-year-old Bismillah, though he does not have any personal recollection of those days. Everyone had “high regard” for arms manufacturers for their contribution to the war against the Soviets. Business is not as brisk these days as it used to be in those distant years. Bismillah makes around 20,000 rupees each month.

He had to close down his shop between 2009 and 2013 when the government put a ban on arms manufacturing to stop weapons being supplied to the Taliban and other militant groups fighting against the Pakistani state and society. He migrated to Peshawar city where he earned his living by driving a taxi.

The tribal law now allows manufacturers to make arms but they cannot sell them within Pakistan. Most manufacturers smuggle their wares to the Pak-Afghan border in Torkham where traders from Peshawar buy them and take them to shops in the city. Often weapons are intercepted and confiscated during smuggling.

And government officials who help smuggling have increased their commission due to increased checking at multiple points along the route. Profit margins have dropped significantly.

Bismillah will readily leave the business if he has another option but he does not know what else to do. “The glorious time is gone. The military has now entered our region … [It] does not allow any weapon to get out of the area.”

Haji Raees Khan, 71, has similar complaints. Sitting with local residents in his outhouse – with a small mosque and a big courtyard of its own – he explains how security agencies view the residents of Darra with suspicion. “We are not considered Pakistani citizens,” he says.

The military’s clampdown on arms trade, according to Raees, is having a negative impact on the local economy. “There were 10,000 shops in the area [in the 2000s]. Now we are left with only 2,000,” he says. If the situation does not change, he adds, Darra’s tradition of arms manufacturing may be lost.

Raees concludes his conversation with a story. “We all celebrated by opening gunfire when Pakistan won a cricket match against India in 2012. Next day, a soldier from Punjab asked local tribesmen why they were cheering for Pakistan.” This, he says, was upsetting. “Punjabis think [Darra] is not part of Pakistan.”

It is evening in Peshawar. Sardar Charanjeet Singh, 40, is thinking of closing his shop for the day. He owns a small grocery store on the Indus Highway just before it enters Peshawar city.

Singh, father of three young children, is scared and wants to get back home before it gets dark. In 2014 and 2015, a number of Sikhs were attacked in Peshawar. The victims included Sardar Sooran Singh who at the time of his murder was working as special assistant on minority affairs to the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa chief minister.

There are around 700 Sikh households in Peshawar. They have been living here for more than two centuries. They speak flawless Pashto, a language their ancestors acquired while living in the tribal areas.

Singh is also an activist for the rights of non-Muslim Pakistanis as well as interfaith harmony. He complains the government does not confer all citizenship rights on non-Muslim Pakistanis. There is no law to register Sikh marriages for instance, he complains.

He is also unhappy with how history is written in textbooks. “My religious hero, Maharaja Ranjit Singh, is mentioned in our textbooks as a thief just because he was not a Muslim.” One of his missions is to get comparative religion introduced in the syllabus in order to “remove all the hatred that is there [among Muslims] for other religions and sects”.

Singh believes he has a better claim to be a Pakistani than many others in the country: many sites he considers holy, including Nankana Sahib, the birthplace of Sikhism’s founder Guru Nanak, are located in Pakistan.

But he rues how Pakistani Muslims do not think that way. After the 2012 cricket match that Pakistan won against India, even his regular customers came to his shop and said how ‘their’ team had beaten ‘his’ team.

“That broke my heart,” he says. “We have been living on this land for centuries but people think I am not a Pakistani just because of my religion.”

A narrow lane lined with shops selling mobile phones leads to a small staircase inside Peshawar’s crowded Qissa Khawani Bazaar. The stairs ascend into a multi-storey building with poorly-lit, small rooms on each floor. Hanif Afridi is sitting in one room on the second floor, rehearsing for a performance at a wedding two days later. At the age of 42, he is the sole provider for his family that consists of his wife, two sons and a disabled sister.

Afridi belongs to Tirah, a valley in the tribal areas that has become a major centre for the Taliban and other religious militants over the last decade or so. He has been singing since his childhood and was once quite famous in his home town for his voice. He was often paid to sing at private and public gatherings.

After militants took over Tirah in 2006, Afridi’s name was announced from a local mosque one day. He was told to see a militant leader the next day. He, instead, fled to Peshawar along with his family. He then shifted to Karachi, hiding there over the next three years or so.

Afridi came back to Peshawar in 2010 and started driving a taxi to earn his living. When that did not earn him enough money, he had to sell his favourite rabab for 15,000 rupees — a move he regrets even today.

Displacement and security concerns have impacted his singing too. Instead of crooning only love songs and cheery melodies, he now also sings about the problems of the tribespeople.

In one recent function, he sang the poetry of Raza Khan Hazir, a poet from Waziristan — “Our houses are bombed. What should we do? We live in tents. Do something so that we get back to normal life.” The audience had tears in their eyes as he sang.

Dr Faizullah Jan was giving a lecture on extremism at the University of Peshawar in November 2008. He told his students a joke about the Taliban. Everyone laughed except one student who warned his teacher: “Please watch your words. You are forcing me to demolish this entire department.” Faizullah did not take the threat seriously.

Two days later, the same student was arrested from the university. He wanted to blow himself up as a suicide bomber. Faizullah was livid when he heard the news about his arrest. “I carefully select words I use in my class. Any student can get offended. I do not know who follows what extremist ideology,” says the 49-year-old teacher of mass communication.

Faizullah has written a book, The Muslim Extremist Discourse: Constructing Us vs Them. It was originally his doctoral thesis. He worked on it while studying in Washington DC in 2009.

The book offers a comparative analysis of publications by different religious groups in Pakistan. “Identity construction is crucial for the extremists,” he says. “They use history, bringing past into present and taking present into past. They have no concept of co-existence.”

Faizullah recalls an incident from his teenage days. General Ziaul Haq was ruling the country at the time and the Soviet-Afghan war was raging. He went to a library to look for a book, titled The Battle of Ideas in Pakistan, written by leftist writer Sibte Hasan.

The catalogue showed the book was available in the library but it was not on the shelves. “I went to the library’s assistant director.” He was associated with Jamaat-e-Islami. The book was piled in his room along with many other volumes by leftist writers. “When I asked him why those books were not on the shelves, he gave me a lecture on why one should not read such books as they take readers away from religion.”

Faizullah says it was, in fact, a state policy to remove such books from libraries and instead introduce a state-imposed ideology. There was a systematic induction of extremist ideologies in universities through student organisations and faculty recruitments, he says. “That is how religious extremist groups became powerful.”

Faizullah advocates the initiation of a robust deradicalisation plan to buck the trend. He remembers reading the book Myths to Live By, written by American author Joseph Campbell. In one of its chapters, Campbell describes how native American tribes treated their soldiers and fighters after they came back from a military expedition.

“Tribal elders stopped them at a distance from the tribe’s members and performed different rituals on them so that young soldiers did not become violent within their own community,” he quotes from the book. “They had to stay away from their tribe as long as it took for them to become normal human beings from warriors.”

Faizullah often travels to Islamabad on weekends with his family. After he crosses the Indus near Attock on his way from Peshawar to the federal capital, he feels he has entered a different world. East of the Indus is a safe, developed Pakistan, he says. West of the river, however, remains “marginalised and terrorised”. This is so because it serves Punjab’s “strategic interests”.

This was originally published in the Herald's March 2017 issue. To read more subscribe to the Herald in print.

All photographs are by the author, who is a travel writer and photographer. He tweets @DanialShah_