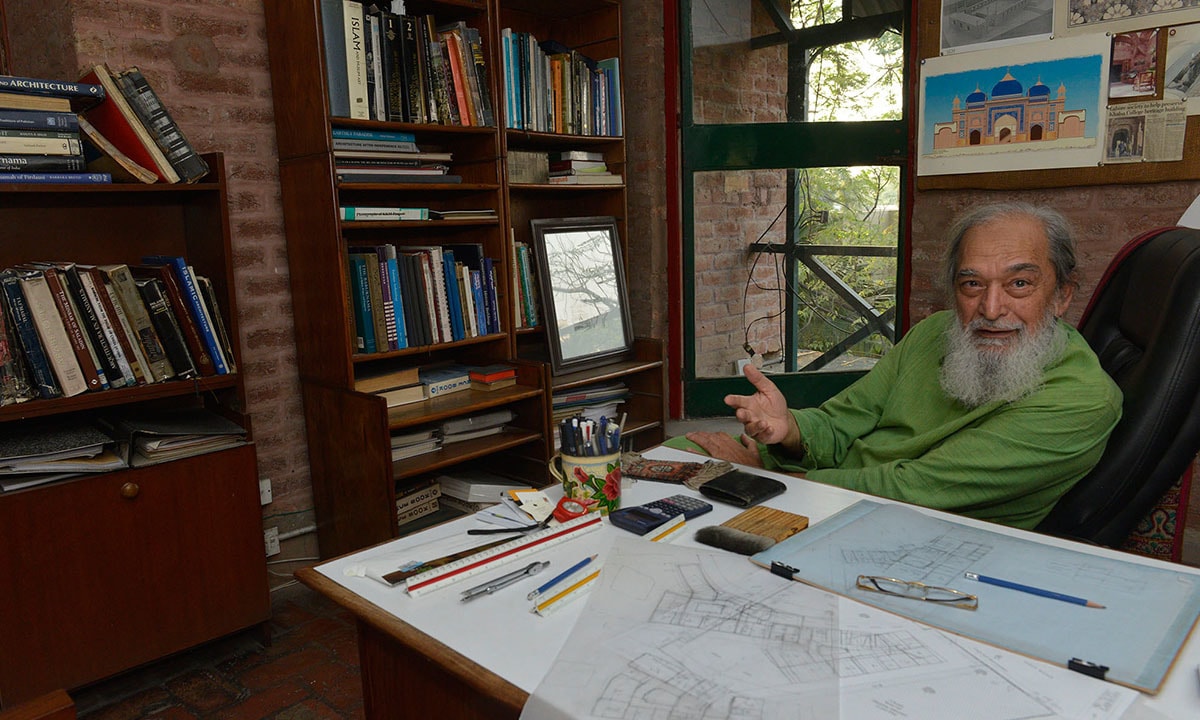

Kamil Khan Mumtaz is synonymous with architecture and tradition. He is well known for his advocacy for the conservation of heritage and environment-friendly development. Mumtaz was one of the founding members of the Lahore Bachao Tehreek in 2006, set up to question the widening of the road flanking the canal in the city. He has also played a central role in civil society opposition to the impact on heritage sites of the Orange Line train project in Lahore, under the mantra that development should take place in sync with the historical and lived experience of the city. In his words, “cultural heritage is … a signifier of the whole complex of distinctive spiritual, material, intellectual and emotional features that characterise a society.”

An interview with him is part predictable, part unsettling, and without fail, leaves one with the pinching realisation that the “crisis” of our time, is in fact not a distant entity for “somebody else” to solve, but one’s very own problem, firmly fixed in our homes and lives.

Mumtaz received his bachelor’s degree in architecture from London’s renowned Architectural Association in 1957, worked in that city for two years, and spent another two years teaching in Ghana. In 1966, he returned to Lahore to join the faculty of the National College of Arts (NCA) as professor and head of the architecture department where he remained till 1975. His students, some of them now in their sixties, remember him as a teacher who would march to the beat of his own drum. He was the inspiring figure who rode a bicycle to work, and carried with himself the Little Red Book of quotations by Mao Zedong.

A philosophical shift came in approximately 1979 when Mumtaz turned towards the exploration of the metaphysical realm via the traditional processes of arts and crafts. This was the beginning of a journey into the world of Sufism for him — both on the professional and personal planes.

With two books to his credit, Architecture in Pakistan (1985) and Modernity and Tradition (1999), he has also been involved in development research such as the well-known Lahore Urban Development and Traffic Study (1980), and institution-building such as the founding of Anjuman-e-Maimaran.

Among his efforts as a practitioner of architecture has been the search for a design appropriate for local climate and economy, as well as locally available technologies and materials. Many of his contemporaries – though they may not agree with his philosophy – argue that he is one of the few architects in Pakistan who have not sacrificed their principles to the whims of the market. Some of his ongoing work includes Daula Pukhta school in Okara district, the mausoleum of Chal-e-Sharif in Gujrat, the conservation of the Lahore High Court and the Governor House, and a number of private residences.

The following conversation with Mumtaz unfolds first in the form of a soliloquy, then a political, historical narrative of mankind’s trajectory on earth, and eventually becomes a tale tied to being and consciousness.

Rabia Ezdi. For several decades now, you have taken a very clear position on the need to preserve architectural heritage in Pakistan. Can you elaborate on this with reference to your activism against the building of the Orange Line train project?

Kamil Khan Mumtaz. Yes, Lahore needs affordable public transport but an elevated metro train is not appropriate for a high-density, low-rise, low-tech, mixed land-use historic city such as Lahore. Moreover, the train is simply not affordable. The state of the art Orange Line [seems] so attractive, so desirable, and would be such a thrill to own and to ride, to go tearing across town in air-conditioned luxury. But the mother has to shake the boy out of his reverie and tell him he cannot have it.

Why do I feel so strongly about it? Because I need this train like I need a hole in my head. This is an unguided cruise missile crashing through the heart of my city.

Cultural heritage is revered by all traditional value systems as a signifier of a society’s spiritual, material, intellectual and emotional characteristics. Old buildings are not to be saved for the sake of visual pleasure but because cultural heritage is the identity of our city.

Heritage, history, traditions — we are told these things must not be allowed to stand in the way of progress and development. Heritage, history, traditions define who we are, where we are, where we are coming from and where we want to go. They define what it means to be human and are the roadmaps, signposts and guides for our journey, our progress and our development towards achieving our goal of realising our highest potentials, our selves. Lose these and you lose the script.

Ezdi. One of your major roles has been that of an institution builder, such as founding the Anjuman-e-Maimaraan ...

Mumtaz. It began with the design of the architecture department course at the NCA in 1966. The Anjuman-e- Maimaran was part of the change in my own thinking — from being a primitive Marxist to a modernist to one who realised the value of tradition. Then came Lahore Conservation Society and from that emerged Lahore Bachao Tehreek and The Lahore Project [a civil society initiative to devise sustainable urban planning for Lahore].

Ezdi. What was your life like growing up?

Mumtaz. Can we not talk about me? I think it is of no interest to anybody and does not need to be talked about. What we need to be talking about is our times. It is much more important to understand what is happening [to us all] than [knowing about] puny individuals and their lives.

Ezdi. People always want to know how individuals like you evolve and become who they are ...

Mumtaz. I have no desire to speak about myself. I have no desire to share my private life with the world. We can certainly talk about our times — the times we live in. What has changed around us, what is the direction that times are taking, what do we need to do, how do we respond to these [situations] as human beings, as architects? I would rather look at these questions objectively than subjectively.

The times that I have lived through have seen the heyday of national liberation movements and anti-imperialist struggles. Modernism and Marxism have been essential to these [movements and struggles]. And Marxism is only another facet of modernism. So, what is the lesson that we learn from modernism, Marxism, colonialism, anti-imperialism? Since then, there has been another big change that is [called] postmodernism. What is the significance of this change and what has actually changed because of it? These questions have impacts on politics, economics, the arts, including architecture and urbanism.

Why I insist on the need to understand the nature of the times in which we are today, [why I insist] that this is what should be our main concern is because we are passing through an unprecedented crisis. It is a global crisis. And it is a crisis that is causing irreversible changes — in the environment, in the biosphere, in life forms including the human species. The real question is: What should be our response? How should we act? The crisis of our time is not for somebody else to solve but a matter of our very own existence and survival; it is rooted in our homes and in our lives.

Ezdi. How did we get here?

Mumtaz. We have seen development and technological breakthroughs in many fields of science since the industrial revolution. This amazing explosion of change [appears] as a higher phase of human progression. If you look at the past 300 years, [the rate of change] is a relatively straight curve [that] shoots up. But if you look at 900,000 years [before that], the rate of change has remained practically steady. There have been no dramatic ups or downs [over the millennia] in man’s relationship with the environment, consumption, global warming, carbon emissions, extinction of species. Even the rate of population growth has remained relatively constant.

The first change [after the beginning of human life on earth] happened 6,000 to 9,000 years ago with [the advent of] agriculture and animal husbandry. You had to settle down or be stationed to be able to plough and harvest. Thus came about villages, towns and cities. The word ‘civilisation’ [has originated from] civitas, which has to do with cities.

The crisis of our time is not for somebody else to solve but a matter of our very own existence and survival; it is rooted in our homes and in our lives.

With [the advent of agriculture and animal husbandry], we saw a sudden jump in production. With increased production, we could support many activities that we could not support before. The surplus was used to support arts, crafts, manufacturing and services like education and health. [All these activities enabled] the producers to produce even more because they had acquired specialised and better knowledge. But there is a limit to how much you can produce within the territory you control — and a limit to how much you can consume. [Those limits have to be] sustainable by the environment. They [should] not overexploit the environment.

Modernism has been the second major change — [that is, the emergence of] modern science and industry. It resulted in a huge jump in production. For that, you needed resources beyond the territory you belong to. You had to look for markets beyond your community. So you acquired more territory [through] imperialist projects, colonisation and world wars — leading to a struggle for the control of the world. This is modernism. What happens when you have controlled all the world’s produce and markets and you have fulfilled all the needs of the world? You invest in science and technology to invent demand — this is consumerism. This is the postmodernist age in which we are.

Obviously developments in science and technology are [made] possible by our understanding of the world — of what is reality. The hunter and gatherer got from nature all he needed: food, clothing and shelter. He saw in natural phenomena the presence of the real — the essential reality, not zaahir, the superficial reality.

With the transition [to agriculture], man saw phenomena that were manifestations of the real. He saw a separation between the cause and the effect. Whereas previously he saw himself as one with the real, now he [sees] himself as separate from it. This realisation was traumatic. The prophets all belonged to this stage [of] civilisation. Their message: How can man reconnect with his origin? This is the meaning of religion — to reconnect, to retie the connection that was broken.

In modernism, however, man [altogether] forgot the real cause of effects which he saw in the material world. [This phase] is 600 to 700 years old, starting with the Renaissance in the 16th century Europe. Postmodernism exploded into our consciousness with [the bombing of] Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It completely shook all humanity. We wondered what was all that.

What happens when you have controlled all the world’s produce and markets and you have fulfilled all the needs of the world?

Einstein’s theory of relativity, that says time and space are not static but moving, completely shattered the Newtonian world view. [It produced] quantum physics and the unleashing of atomic and subatomic forces. The Newtonian world view is that the universe is governed by absolute and constant forces of nature. Quantum physics brought with it the unpredictable. It says that physics cannot know the nature of the universe, that we cannot say what matter is and what energy is. So, you have alternate, parallel realities existing simultaneously. This new understanding of nature necessitated an answer from the philosophers as to what is the nature of truth. They could only say there is no absolute truth.

Ezdi. And what is at the core of the crisis of our time?

Mumtaz. To understand where we stand today, we have to understand where we are coming from. [You have to] understand the human condition and our relation to our environment. [It was] during modernism that we began over-exploitation of the planet’s resources. [Now we have moved] to consumerism which breaks all bounds. The result of this is precisely the global crisis that we are in. The question is: Knowing the nature of our times, how should we act? Most of us, of course, are completely swept away by this whirlwind 24/7 thrilling ride. Every day, [there is] a new sensation. And we are too busy in having this fun. But now things have got to a point where you can no longer deny the crisis that we have created.

Ezdi. Is there anything we can do? Is it time for a revolution of sorts?

Mumtaz. Most of those who are concerned about these situations are looking for a mitigation of bad effects. We do not want to reverse [anything] because we are told that [economic growth] is the destiny of mankind. So, we must only know how to achieve that without damaging the environment and other species. You have all kinds of critiques of modernism and postmodernism but the bottom line is that they are all looking for ways to achieve economic growth without damaging the environment — ‘green architecture’, ‘sustainability’, all the buzz words.

But I talk about looking at all this in [historical] perspective. Change in nature is constant but where do we get this idea of mankind progressing forever? Having stayed steady for 800,000 to 900,000 years, the change is suddenly approaching infinity. There are only two moments in the life of anything at which the rate of change is infinite. First, when it comes into existence — from nothing into something. With time, it attains a normative state that endures for some time and then it atrophies and degenerates out of existence. This terminal stage is the second moment of infinite change.

What is happening now is not a normal event. It is an abnormality, an abomination, an aberration. The short time in which the curve [of change] has started approaching infinity [is alarming]. When I first looked at the statistics some years ago, one species or form of life was going extinct every 20 minutes. A year or two ago when I checked again, one species or form of life was going extinct every 11 minutes. The latest rate of the extinction of a species or form of life is every four minutes. The rate of extinction is multiplying. It is the same with global warming. And it is all interconnected and irreversible.

It is also not just the biological species [that are dying]; it is our humanity embedded in our languages [that] is going extinct. Four to five years ago, the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organisation (Unesco) figure was that one language was going extinct every fortnight. A whole culture is lost with every language, every word [that goes extinct].

To imagine that we can engineer, tweak our way out of this crisis is delusional. How should we then act in these times is a big question. What should we do?

But cities of today are the biggest contributors to the present global crisis. Postmodernism has taken the rug from beneath our feet and we are in free fall.

In the postmodern age, there is also a denial of anything absolutely right or absolutely wrong. We should, therefore, first discriminate between right and wrong and then do what is right. Not because we expect to change the world but because it is the right thing to do.

Ezdi. What concrete measures can we take in terms of our institutions, for example? Let us take the case of higher education ...

Mumtaz. Of course, our higher education systems are part of the problem. They promote and train our next generation to do what we have been doing — more of the same. We prepare them to destroy the world faster. Education is now one of the few growth industries [that also include] health, real estate and art.

We have these newer production units cropping up — there are 24 schools of architecture in Pakistan. I understand 21 of them have received notices from Pakistan Council of Architects and Town Planners. Clearly something is amiss.

We treat education like any other business enterprise. But what the customer wants, what the market demands and what is the need of the hour are three different things. The customer – the student who buys the education – wants a ticket to success, to become rich and famous. What the market demands is slaves — good draftsmen, good 3-D graphics people, good visual designers and interior designers. But what is the need of the hour is to approach architecture with the knowledge of the realities of our time.

Ezdi. Let us talk about urban planning. What does it need to do better?

Mumtaz. Like everything, urban planning has also been impacted by epochal changes. When the cities were ruled by lords, kings, emperors, [they maintained] a feudal hierarchy [in their environment] and their planning was for defence purposes. Much of what we see today is a result of modernism and the possibilities created by machines, science and technology. So, we dreamed of [cities as] machines — consider, for instance, Le Corbusier’s architecture and skyscrapers. But beneath this was still an altruism and idealism — the principles of equality and non-discrimination among human beings. The centre of this new universe was man, not God. [The modernist world view was imbued with the] idea of universalism, the brotherhood of mankind and democracy.

But cities of today are the biggest contributors to the present global crisis. Postmodernism has taken the rug from beneath our feet and we are in free fall. We have no ideals, no principles. All we want is to make a splash, to make a name for ourselves, to make money. The Shanghais of the world are taking off into some fantasy which is part of this destructive process.

Yes, the cities are seen as engines of growth. That is precisely what is destroying the planet. We talk of a sustainable planet but no city is sustainable by definition. Cities are parasites; they cannot survive without a host region [to feed their need for resources].

In this post-industrial reign of global capital, wealth is also concentrated in the cities. The shining glittering city thus becomes a symbol of progress and development. In economies like ours – the client states – cities are just middlemen for transferring wealth to developed nations. And like middlemen, the cities take a cut from that wealth.

But when you get to a city, it is not that [you see] everyone rolling in wealth. [Wealth] is in the hands of the one per cent — a case of concentration upon concentration.

As Gandhi said: “The world has enough for everyone’s need, but not enough for everyone’s greed.” Needs are finite and limited

What we should think about is this: If cities are destroying the planet, let us stop building more cities. We instead are thinking of new ways of extorting the world’s wealth [through] intelligent cities, smart cities, etc. Now you can buy green products such as green architecture – all just labels – because this is what sells.

Ezdi. So, can architecture change the world?

Mumtaz. It is too late. Do you think you can bring down that exponential change in the growth curve? Or you can reverse it? You can, however, do what you believe is right. Do whatever you can, wherever you can. Do it but don’t do it to bring about a revolution.

Ezdi. Do you see young people taking up these causes with as much passion and commitment as you have?

Mumtaz. I keep being surprised by the number of people who are seriously seeking answers and are troubled by the institutions they are studying at and by the world around them. They sense and feel that there is something wrong. They are looking for alternatives.

Ezdi. What would you say to the young idealist of today who is constrained to earn his living but still wants to bring change?

Mumtaz. Each one of us has a responsibility to preserve ourselves, our health and our physical well-being. We are placed in this world in these bodies. We cannot deny our responsibility towards them. The world, our families and our bodies have a right on us. [It is our] responsibility to ensure that we do not neglect to provide what we need. The trouble is that we want more than what we need. That becomes greed. The moment you chase more than what you need, you become part of the trouble.

As Gandhi said: “The world has enough for everyone’s need, but not enough for everyone’s greed.” Needs are finite and limited. You cannot eat or drink more water than a certain amount. You cannot breathe more oxygen [than your body requires]. But greed and desire have no limit. You always want more. As the advertisement says: ye dil mangay more (the heart craves for more).

Ezdi. Would you say that the lack of spirituality lies at the core of this embracing of greed?

Mumtaz. Nature has been generous and provides everything we need. There has been no reason to accumulate more than we need. On the other hand, there has always been [the urge] to store. Both spirituality and greed, thus, have always been a part of human nature.

With agriculture and animal husbandry, it became possible to acquire luxuries, to enjoy the arts. Anyone who had the power – muscle power, political power or weapons – turned towards accumulating the surplus so that they could do those things which one could do with surplus wealth.

The desire to accumulate feeds itself and it went out of the ballpark in the industrial production. When you produce industrial surplus, what do you do with it? Do you give it away? That is the last thing you want to do. So you store it – as insurance – or you reinvest it in your industries, with the result that you produce even more. The greed factor thus multiplies.

In the age of consumerism, you want instant gratification. The greed for sensation and power has gone berserk. These tendencies have always been within human nature but previously civilised man recognised these as evil. He recognised charity as virtue. What is evil and what is virtue now? Spoil yourself and flaunt [your wealth]. We have stopped calling it wrong. People say ‘that is what life is about’. The world has been turned upside down. The seven deadly sins are now the seven deadly virtues.

I keep being surprised by the number of people who are seriously seeking answers and are troubled by the institutions they are studying at and by the world around them.

To be kind and compassionate is seen as a disadvantage. When Michael Jackson says ‘I’m bad’, that is the highest compliment he can pay himself. What was a no-no is now the mantra of business — ‘young man, go market yourself, sell yourself’. Even in architecture, we were taught not to advertise ourselves. Now advertising is [everywhere].

Ezdi. Victor Hugo said, “Nothing is more powerful than an idea whose time has come.” What is the most powerful, world-altering idea of our time?

Mumtaz. The idea we have to slow down is beginning to gain more and more traction. Essentially, the problem is the whole modernist paradigm, particularly that of economic growth. Given what is happening to us, to our world, we are gradually beginning to hear serious voices calling for a paradigm shift — for instance, voices criticising the mess of postmodernist art and architecture. I am thinking of [Canadian-American architect] Frank Gehry saying, “98 per cent of what gets built and designed today is pure s**t”. David Hickey, the [American] art critic who [recently] retired from art writing, realised that art has been reduced to money transactions and investment options and has seized to be art altogether. It is like the emperor has always had no clothes but nobody has said it all this time.

There is realisation that something is seriously wrong with the way we are living. There are serious concerns about what drives consumerism — that is, greed. Until last year, we had serious writers praising greed as the oil that makes the capitalist machine flourish. I think there are people now who are seriously questioning that. They are realising that there is more to life than the pursuit of a material paradise.

Ezdi. Are you satisfied with what you have contributed to the world in your lifetime?

Mumtaz. First of all, I have no delusions in terms of what I have contributed to the world. I have only tried to be true to what I believe in and to live accordingly. If that has benefitted anyone, I am grateful for that.

Correction: The article's earlier headline misquoted Mumtaz as saying "I need this train like I need a bullet in my head". We apologise.

This article was originally published in the Herald's November 2016 issue under the headline, 'The architect of ideas'. To read more subscribe to the Herald in print.

The writer is an Associate Professor in the Department of Architecture, National College of Arts, Lahore.