“[T]ime is running out,” warned a short essay written in Urdu and circulated on WhatsApp in late September this year.

The writer, who did not identify himself, alleged how a private education network, Beaconhouse School System, was pursuing an “Indian agenda” and promoting “western” values among its students. He expressed alarm at the rapid pace at which these students from the “elite class” were joining important positions in state institutions. “A large chunk of this lot is also entering the armed forces and it is obvious that they are not joining the forces to become soldiers,” he wrote.

He also gave a brief history of the school system, a short description of the political leanings of its owners and an overview of its curriculum. This was perhaps meant to give the impression that whoever wrote the essay knew his subject well. He was also intelligent enough to bring in a reference to something that many people do not like about private school systems: high fees. “Beaconhouse squeezes one billion to five billion rupees per month … from people,” he wrote before calling the school system an “enemy of the state” and labeling its students as “liberals” who indulge in immoral practices.

To substantiate these claims, the writer referred to the alleged writings of one Ayaz Nizami, a blogger imprisoned over blasphemy charges since March 2017. “We have infiltrated your colleges and universities with our professors and lecturers who will destroy the new generation’s ideology that supports your existence…They will see your enemies as heroes and you as a villain. They will see the ideology of Pakistan as a burden,” the essay quoted Nizami to have written.

It concluded by alleging that the Beaconhouse School System had initiated a “war” against Pakistan in the name of “education” and that the media and the courts appeared powerless to stop it.

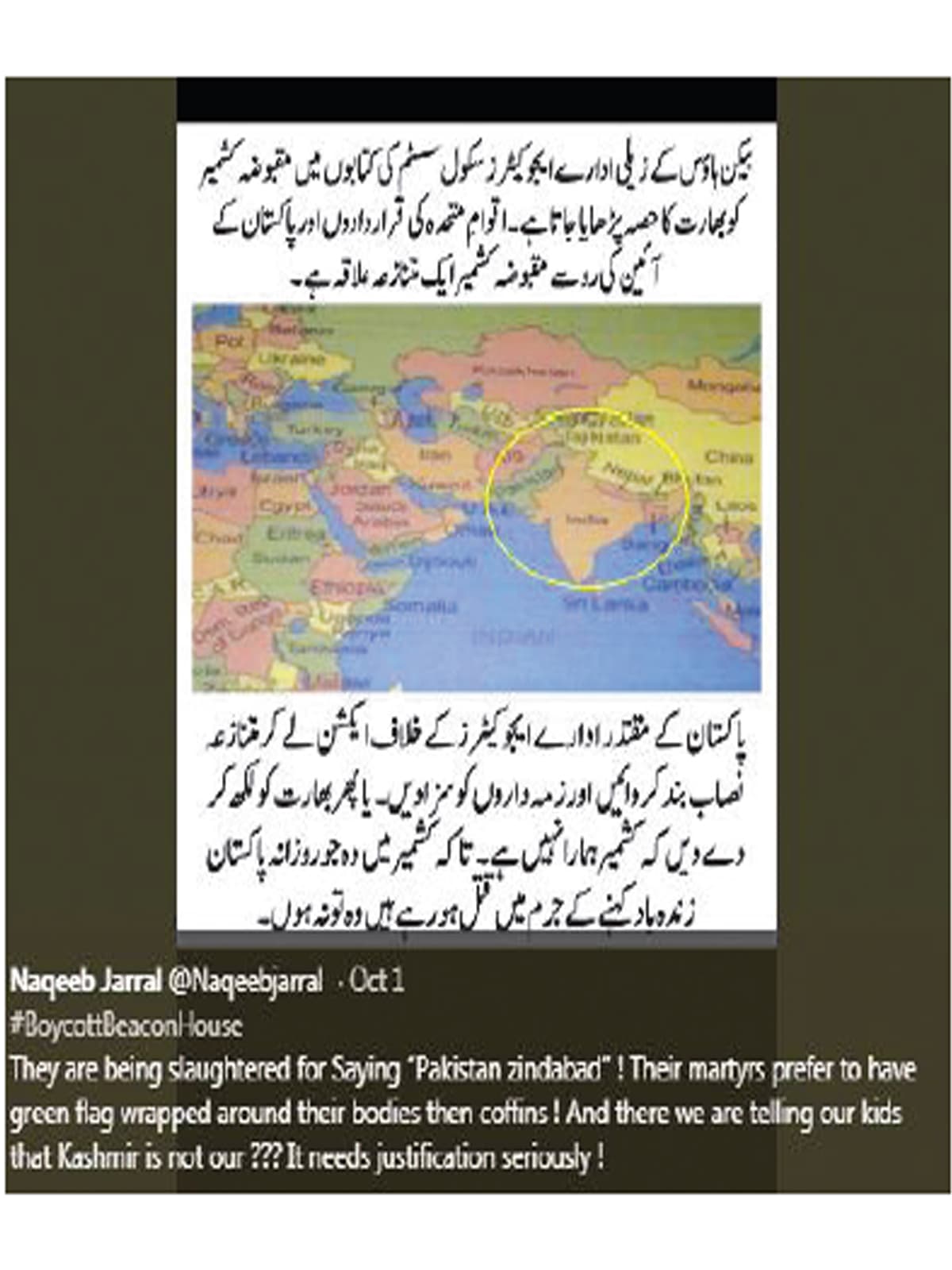

In just two days after the essay was first circulated, one person’s tirade became a whole campaign. Hashtag #BoycottBeaconHouse was soon trending at the top of Twitter Pakistan charts. Over the next couple of days, it was retweeted more than 37,000 times.

A vast majority – 80 per cent – of the Twitter accounts involved in this propaganda campaign were from Pakistan. Another 9.6 per cent were from Saudi Arabia. Most of the rest were from Malaysia, Spain and the Philippines. A majority of them were not fake; the number of tweets generated by either bots or as bulk/spam was fairly low.

A large part of the content used for promoting the hashtag (both in English and Urdu) was the same, suggesting that the campaign to discredit the school was a coordinated one. The content was also being generated and shared by a certain group of people who routinely indulge in online propaganda.

The most replicated tweet was: “#BoycottBeaconHouse It is time we hit back at the deep subversion against the State being done by Indian funded schools.” The tweet also stated that it is understandable that former president Asif Ali Zardari and former prime minister Nawaz Sharif allowed this “subversion” but there is no excuse for it now because Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) has come to power. “We are pointing it out strongly ..... This is treason by Beaconhouse.”

The web link that received the most traction on Twitter during the campaign belonged to some students who were allegedly studying at the Beaconhouse School System. The link talked about menstruation. In addition to it, some images were circulated that showed some students dancing inside a school. Photoshopped memes were also circulated to back the allegations against the school.

At the core of the campaign was a map in a textbook used by The Educators, a subsidiary of the Beaconhouse School System. The map did not show Indian-controlled Kashmir as a part of Pakistan.

Kasim Kasuri, chief executive officer of the Beaconhouse School System, says that, contrary to what people behind the campaign wanted everyone to believe, the map was not made by his educational network. It was part of a book written by a foreign author and published by the Oxford University Press, he says. “It was used by many educational institutions including the Army Public Schools.” But, he says, the book was retracted and the map was rectified much before the campaign began.

Kasuri claims the campaign was not a single person’s doing but was instead engineered and sponsored. “We lodged an application, asking the cybercrime wing of the Federal Investigation Agency (FIA) to identify the people behind it and take action against them,” he says. No action has been taken yet, he says, and the “objectionable” content is still available online.

Aviral WhatsApp message disseminated a few months ago talked about a “strategy to eliminate Imran Khan’s government” right after he had come into power. “The American intelligence agency CIA has launched a media war to ensure the downfall of Imran Khan’s government,” the message said and added that a virtual warfare “has been imposed on Pakistan and Imran Khan is the primary target of this war”.

In the first stage of this war, the message read, a vicious media campaign and propaganda would be launched against the government. “Social media will be key part of this campaign,” it said and went on to allege that all opposition parties were part of this strategy to “destroy” the PTI government.

Such deployment of social media in what appears to be a war of political, ideological and geostrategic narratives is being summed up in a self-explanatory term: “Fifth-generation warfare”.

The term refers to the use of misinformation and other non-kinetic means, such as fake news and propaganda, to portray one’s own side as a victim of conspiracies and intrigues by others. For the likes of Zaid Hamid, a media commentator known for his hyper-nationalist, uber-Islamist rhetoric, Pakistan is “truly under attack” in what he calls the final stage of an information war being waged by the country’s enemies.

In early November this year, protests by religious groups over the acquittal of a Christian woman, Aasia Bibi, in a blasphemy case triggered yet another round of such alarmist conspiracy theories on social media. A hashtag, #5thGenWar, claimed that an international conspiracy was being hatched to destablise the government in particular and the country in general.

“Former Indian Army Chief explaining the Indian #5thGenWar against Pakistan being waged by India ... Support to internal insurgencies, religious and sectarian wars, ethnic clashes, provincial disharmony, political chaos, economic collapse ... assassinations, terrorism and urban war,” read the most shared and replicated tweet from this hashtag.

While most of these tweets were sent out in English and Urdu, a few of them were also posted in Hindi probably to reach out to Twitter users across the border. Apart from Pakistan, most of the activity under this hashtag originated from the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

The fifth-generation warfare is also a popular topic of discussion on the Defence.pk website. It warns its users – who are mostly young – that social media is being used as a “war platform” by enemies of Pakistan.

Pakistan, though, is not the only country where such propaganda wars are rife. Nor is the present the only time when propaganda is being employed for political, ideological and geostrategic purposes. “Propaganda is as old as war itself but social media has allowed information operations a scope, reach and speed that was previously unthinkable,” says David Patrikarakos, a London-based journalist and author of War in 140 characters: How social media is reshaping conflict in the 21st century.

“If you look, for example, at the downing of [Malaysia Airlines Flight 17] over eastern Ukraine in 2014, you can see this [idea] in action,” he says in an interview. The Ukrainian government and a Russia-backed rebel militia were locked in a civil war at the time. “It took only minutes for Russian trolls to flood social media with many contrasting propaganda narratives that went viral and, therefore, global,” he says.

One theory suggested that the flight was shot down by a plane, not by a ground-to-air missile. Another linked the plane’s mid-air explosion to a plot to kill Russia’s President Vladimir Putin. Pravda, a digital news platform based in Russia, in fact, published a story based on the same theory. Titled MH17: some conclusions — did Nato try to murder Putin?, the story alleged that Putin was believed to be flying the same route as the Malaysian airliner at the very same time and that his aircraft had “very similar contours and colouring”.

No matter how outlandish these theories sound, they served their purpose successfully. “The disinformation campaign [around the flight] shows how initially successful [propaganda] can be,” says Patrikarakos. “Obviously the …lies were eventually debunked but by then their narrative had been fixed in many people’s minds.” That, he says, is the overarching goal of propagandists: “The more doubt you can sow in people’s minds about all information, the more you will weaken their propensity to recognise the truth.”

The use of social media in India to promote an aggressive Indian nationalism further explains how all this is done. Fake news with nationalistic messages are being very eagerly shared and propagated in India, according to a recent BBC research, even when people know they are not genuine. The need to accentuate national identity is certainly taking precedence over the need to fact-check.

Propaganda also does not always need to have a political and geostrategic agenda.

Earlier this year, a video surfaced on social media discouraging people from getting their children vaccinated against polio. The video alleged the vaccination was a “conspiracy” by Bill Gates, the co-founder of software giant Microsoft, whose Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation donates large sums of money every year for polio vaccination in different parts of the world. “Bill Gates, the billionaire, started an initiative to end polio in Africa and other countries like India and Pakistan. Bill Gates, along with Melinda Gates, is working towards ending polio from the world. People say there is something missing in this programme,” read the text shown in the video (which is still available on YouTube).

The ‘missing’ part was then ‘revealed’ by claiming that the “vaccine prepared by Bill Gates has a chemical which weakens and destroys sperms so that when boys grow up, they do not have the ability to procreate”. All this was explained as a “Zionist conspiracy” to reduce the global population from its current level of around seven billion to just one billion. “Or to reduce the population to such an extent that only Jews are left behind, with their fake messiah Dajjal ruling over them,” the video claimed. “To achieve this, they have introduced several measures, including polio vaccine.”

The video, made in Urdu, was viewed 465,611 times and attracted 9,100 likes. Several other videos targeting polio vaccination are also available on YouTube and have been viewed thousands of times.

In March this year, for instance, daily Dawn reported from Nawabshah, a city in central Sindh, that a video was being circulated there which showed someone claiming that polio vaccine was killing children. When officials of the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA), that regulates internet in the country, investigated the origin of the video, they found out that the footage and the voiceover were done separately. The promoters of the video had curated some random footage and then dubbed it with their own message.

These anti-vaccination videos have resulted in a dramatic increase in refusals by parents to let their children receive anti-polio drops even in areas where there was no history of such refusals — such as Dadu district in Sindh. A report by the British daily Telegraph claimed as many as 70,000 refusals were reported from different parts of Pakistan in May this year alone.

The narratives being pushed online are certainly influencing public perceptions offline.

A screenshot of a Bol television channel’s news ticker showed Major General Asif Ghafoor, director-general of the Inter-Services Public Relations (ISPR), which is the media wing of the armed forces, as saying that an anti-state campaign was going on in the country to defame the armed forces. “If abuse is hurled at the forces then full action will be taken. Please help us trace these traitors,” the ticker quoted him as saying. It also carried a list of telephone numbers and an email address that people could use to inform the ISPR about “these traitors”.

The image was posted on social media on November 5 with a caption that read: “Share this as much as possible so that the news reaches the whole country and whoever dares to criticise the army is taken to task.” The post received over 7,000 shares within half a day of being posted.

The screenshot, as well as its contents, were soon revealed to be fake. The ISPR had issued no such statement.

Earlier, in June this year, a screenshot of a Facebook post by Dawn.com, Dawn Media Group’s news website, surfaced on social media. Its contents wanted people to believe that Afghanistan had finally accepted the British-era Durand Line as its official border with Pakistan. The post carried an image of Afghan National Security Adviser Hanif Atmar and Pakistan’s Chief of Army Staff General Qamar Javed Bajwa and claimed that the recognition of the Durand Line was discussed in a meeting between the two.

The image included so many defining elements from Dawn.com’s social media and Facebook layout that it led the Afghan National Security Council to issue a press release to say that no meeting between Bajwa and Atmar had taken place. Like many other social media users, the Afghans assumed that the post was legitimate.

It was not. Its content was manufactured and its layout doctored.

Such fake screenshots of news media outlets mostly emerge on Facebook which has a broad user base as opposed to Twitter where users are mostly, if not entirely, politically-engaged. The latter are more likely to detect the doctoring – and sooner – than the former.

Detection is still never as swift as the spread of the propaganda. The Internet and social media are expanding at such a breakneck pace that fake news and misinformation seem to be travelling at the speed of light.

Roughly 500 million tweets are sent each day and nearly seven hours of footage is uploaded on YouTube every second in 76 languages, say Emerson T Brooking and P W Singer who work with New America, previously the New America Foundation, a non-profit research organisation based in Washington DC. The two, who have written a book together, LikeWar: The Weaponization of Social Media, also state that around 3.4 billion people in the world – slightly less than half of the global population – now use the Internet.

Data for Pakistan suggests a similarly deep penetration of the Internet. According to PTA, there are 62 million subscribers of high speed broadband Internet in the country. The immense size of the digital universe makes it easy to disseminate manipulated and doctored images/video clips without much scrutiny.

Technological advances, meanwhile, are making the detection of manipulation even harder. Run a video at a higher, or lower, than its actual speed and it may suggest something that did not take place at all.

The most famous recent video with an allegedly changed speed shows a CNN reporter Jim Acosta trying to retain a microphone to ask American President Donald Trump a question during a press conference at the White House. The CNN has accused the Trump administration of doctoring the video to suggest that Acosta touched a White House intern inappropriately as she approached him to take the microphone away.

Also consider a picture of foreign minister Shah Mehmood Qureshi, circulated on social media on October 1 this year, showing him receiving a standing ovation at the United Nations General Assembly. The image was propagated on social media by PTI supporters to claim how the party’s newly-elected government was being warmly welcomed by people from across the globe. Prime Minister Imran Khan at the time was being criticised by leaders of opposition parties for not going to the General Assembly himself. The image indirectly addressed the criticism with a caption that said: “When leaders are honest then the world will respect them. Look at the respect for Foreign Minister in America because behind him is the lion – the truthful and trustworthy Prime Minister.”

The image was anything but genuine. The audience shown in it cheering for Qureshi was actually doing so for Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan at a July 24, 2018 event at the Grand National Assembly of Turkey.

A troll in ancient myths is an ugly creature that can be either a giant or a dwarf. It lives in dark places – such as caves and caverns – waiting to snatch anything that can pass off as a quick meal.

Lifewire, a technology website based in New York, defines an internet troll as a modern version of the same mythical character. They hide behind their computer screens and go out of their way to cause trouble on the Internet. Like its mythical predecessor, an internet troll is both angry and disruptive — often for no real reason.

In Pakistan’s case, a troll usually identifies himself or herself as a “patriot”, “Muslim”, “pro-army”, “pro-Kashmir” and a PTI supporter. There are also liberal and leftist trolls as well as those who ostensibly claim to promote the cause of various ethnic and religious minorities. The trolls operate in swarms and act like bullies, collectively attacking anyone who opposes their views. Also like bullies, they disperse as soon as they face a counter-attack.

Most trolls have a large number of followers who generally share their personal and political views, and also ideologies. Trolls with their own pictures on their social media profiles are mostly based abroad. They are usually the ones to take the lead in picking and attacking a target. Soon after a troll with a ‘real’ profile has fired the first salvo, a large number of anonymous trolls follow up on that. They either repeat the original attack or add more firepower to it. If users of social media block one of these anonymous accounts, it is simply closed down and a new one is opened in its place immediately.

Some of these trolls have become quite known due to their involvement in numerous propaganda campaigns on social media. An analysis of 10 different hashtags, including #BoycottBeaconHouse and #5thGenWar, which have promoted hyper-nationalistic contents recently, shows Farhan Virk as a part of all of them. He is famous for initiating and promoting many nationalistic and pro-PTI Twitter trends in recent years.

In an earlier interview with the Herald, Virk had explained how misinformation is put on technological steroids through hashtags. “It takes just a single account with a major following to retweet [a fake] post at peak time and the message goes viral,” he had said. For most of the hashtags initiated and promoted by him (and his associates), the influencer (a person with a large social media following) is Zaid Hamid, one of the loudest exponents of various anti-Pakistan and anti-Islam conspiracy theories.

Another social media account always pushing these hashtags purportedly belongs to one Dr Aliya Kareem. She tweets with the handle @draliya7 and her account, made in December 2011, has 50,000 followers.

Kareem’s Twitter profile describes her as a “taxpayer” and a “proud Pakistani” who loves Imran Khan and the Pakistan Army. Her profile picture is that of a young woman standing behind what looks like an Imran Khan poster. Her profiles on Facebook and Instagram do not have the same photo. The Instagram profile has a low-resolution picture of a woman with her head tilted down. It is difficult to tell if she is the same person as in Kareem’s Twitter profile. Her Instagram account describes her as a student of medicine who lives in Karachi and loves food and traveling.

Kareem has sent out a total of 253,000 tweets (as of November 16). Mostly, these are either retweets of what other PTI associates have tweeted or they praise the party’s top leadership.

Countless other accounts similarly maintain an active online presence but do not leave any major traces about their real life existence. They could be what information technology insiders call “human-bots” — real people working like robots to repeat and replicate social media contents on behalf of people, parties and institutions that employ them. They are often deployed to propagate partisan misinformation, to push a particular political narrative and/or to blend engineered political ideas into genuine media content. They are also used for harassing, heckling and intimidating political rivals and journalists.

Such human-bots were deployed by all major political parties prior to the general elections in July this year, says Media Matters for Democracy, a policy research organisation based in Islamabad. The organisation set up a team that monitored 37 Pakistani Twitter hashtags with political content from June 23 to June 30. The monitors found out that most of those hashtags, except #Election2018, involved large-scale engineered activity comprising 800,000 tweets, retweets and replies. This suggests that the promoters of those hashtags were making concerted efforts to amplify their messages.

The monitors noted another common feature: some human-bots in each of the hashtags were inciting violence against political rivals — a dangerous trend that no political leader stopped or even condemned.

There is often a duplication of content in campaigns run by human-bots, says Sheheryar Popalzai, a data and technology journalist based in Karachi. This means that someone is providing them the same content which they then share through WhatsApp/email at a mass scale, he says. There are also no replies to the tweets that use propaganda hashtags, according to him. “This suggests they only want to grab attention for the time being.”

Popalzai regularly monitors the Internet and social media in Pakistan. He has devised an online tool – Project Shikari – with funding from the International Centre for Journalism (ICFJ) to analyse the contents of hashtags on Twitter and to see how they are used for pushing political agendas and promoting partisan propaganda.

His analysis shows human-bots operate differently from botnets or virtual robots. Botnets push the contents at very regular intervals – say, to send out five tweets each day – but human-bots exhibit random booms and bursts in their online activity, depending on whether and when they are required to carry out a campaign, he explains.

An important challenge pertaining to the accounts operated by human-bots is that, in order to be seen as genuine, they need to have followers.

A Google search throws up the name of ZV Market, an online marketplace where dozens of vendors are selling “real followers” for as low as two US dollars per account. One of its adverts reads: “Real & Active people. No Bots or proxy … Choose from 100 followers to 5,000,000 that we offer depending upon your needs.”

When approached through the chat option on the market’s website, the person on the other side insists that the services the market is providing are not in violation of any Twitter rule — implying that the followers being sold are real people. He also promises to ensure that the number of followers will never drop. “We are giving you a lifetime guarantee that no followers will ever drop. If any followers get drop, I will refund you the whole payment,” he says.

When the vendor is asked how followers purchased online in bulk can be made to follow other accounts overnight, he does not respond.

Popalzai rubbishes his claim that the followers are real people. They are only botnets, he says. And since they are botnets, he argues, “there is no way to ‘guarantee’ that their number will never drop”. This is because Twitter actively seeks them out and deletes them.

In neighbouring India, journalist Swati Chaturvedi has written a book to explain how an “army of trolls” works. She claims the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has engaged a huge network of volunteers and paid workers who are used, along with sophisticated bots, to attack journalists, political rivals and anyone who opposes the party. These trolls also disseminate false images and doctored reports to heighten communal tensions, she says.

They are coordinated through WhatsApp, she says in a phone interview, which is used to send them instructions on a daily basis. “Each troll has a contact [person] in the [party’s central social media] cell who sends them daily instructions regarding the content to push out,” says Swati, whose book, I Am a Troll, has recently won an award from the Reporters Sans Frontiéres, a France-based non-governmental organisation working on issues pertaining to journalism.

These BJP trolls, according to her, “are staunchly anti-Muslim and chauvinistic and resentful of liberal elites [that] English speaking journalists represent.” They also target those who challenge their party’s narrative. “Before my book came out, they systematically downgraded it [by writing negative reviews] on Amazon. They are highly organised.”

According to Swati, Modi himself follows two dozen of these troll accounts on Twitter and their work has won accolades from the BJP’s top leadership. “It does not matter if it is a lie or a truth; we can make anything viral,” is how, according to her, BJP’s president Amit Shah once boasted about their operations.

In Pakistan, the ruling PTI is a pioneer in the use of social media and has long been in the spotlight for trying to engineer politics through digital spaces. The incumbent information minister, Fawad Chaudhry, who was then in a rival party, alleged in 2012 that the “PTI paid 780 persons on a monthly basis just to abuse on [Facebook] and Twitter.”

Times have changed.

The same party is now intent upon curbing online propaganda. A few weeks after it came to power in August 2018, it set up a FakeNewsBuster account on Twitter under the Chaudhry-led Ministry of Information and Broadcasting. The irony is that its look-alike Twitter handle emerged just a few days later — with the same display picture, title and information as in the original.

How will general users sift the fake from the original, especially given that even seasoned journalists, senior politicians and even federal ministers have failed to do so in recent weeks and months?

A renowned talk-show host recently apologised for retweeting a message from a Twitter account posing as belonging to Indian cricketer-turned-politician Navjot Singh Sidhu. Rehman Malik, a former interior minister and a senator of the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP), is known to have sent a tweet to a fake account created under the name of American President Donald Trump. Chaudhry himself has made the same mistake.

On November 24, only days before Pakistan and India inaugurated construction work on a border corridor to provide passage to Indian Sikhs to reach a gurdwara in Kartarpur village on the Pakistani side, a Twitter handle (@NavjotSSi) tweeted: “Today I have been invited by the Government of Pakistan On the occasion of opening the #KartarpurCorridor. I am grateful 2Prime Minister Imran khan & Army chief. All Sikh community is thankful 2Pakistan. Pakistan is my second home. And I’ll definitely come on this happy occasion.”

The message generated over 20,500 likes and over 3,100 retweets. Chaudhry, who also follows the account, was among those who retweeted the message — without realising that it came from a fake account.

Asma Shirazi, a television talk-show host based in Islamabad, was accompanying former prime minister Nawaz Sharif and his daughter Maryam Nawaz as the duo flew from London to Pakistan in order to undergo imprisonment for conviction in a corruption case. Soon after their arrest in July this year, video snippets of a conversation between Sharif and Asma started circulating on social media. The heavily edited clip showed Sharif complaining about his ‘exclusive’ interview with Asma that had not been aired. She can be heard telling him what had hindered the airing of the interview.

Within hours after the clip emerged, it triggered a mass social media campaign against Asma. Many Twitter users accused her of being a paid agent of the ousted prime minister. Others claimed she cried when Sharif and his daughter were arrested.

“The campaign was a mix of fake news, character assassination, slander and abuse to dent my credibility as a journalist,” says Asma in an interview. “It led to more cyber bullying that continued for days,” she says. Its negative impact, according to her, is still visible on her social media feeds.

Many of the accounts that started the campaign against her, Asma claims, were based abroad. “These would tweet one thing and a farm of troll accounts, each with 60 or less followers, would follow suit.” The abuse was more personal on Facebook, WhatsApp and YouTube than on Twitter. “On Facebook, it was particularly filthy,” she says. “I received threats of both rape and death.”

Asma did not seek any legal action against the campaign. “There is no point. Trolls hurl abuse and intimidate journalists on a regular basis,” she says and points out that, ironically, it is the journalists, and not the ones who harass them online, who are facing censorship.

Digital Rights Foundation, a Lahore-based non-governmental organisation working on digital issues, has found another worrying pattern in social media campaigns: the abuse is particularly obnoxious and widespread when women are its targets. The organisation analysed 43,372 comments from the Facebook pages of 40 women politicians belonging to major political parties. Out of these, 2,262 comments (5 per cent) could not be classified in any category. The remaining were classified as sexist (25 per cent), abusive (23 per cent), threatening (2 per cent) and racist (1 per cent).

Abuse and personal attacks are often meant to divert attention from real, substantive issues, according to Imaan Hazir Mazari, a YouTube blogger based in Vienna whose mother, Shireen Mazari, is the federal minister for human rights. “When people resort to abuse or personal attacks, attention is automatically shifted from [issues] under discussion to abuse itself,” she says.

Imaan has often been in digital hot waters merely for voicing her political views. “I receive a flood of abusive comments, including death threats, on my YouTube channel and on my Facebook account,” she says.

But, as Imaan argues, the targetting of people who are outspoken about their political views is not entirely unexpected in a bitterly divided country like Pakistan. “There is a clear divide between those who hold secular, liberal and progressive values and those who are conservative in their thinking. Due to a lack of dialogue between these two opposing poles, their frustration [about] and disconnect [with each other] is seen on social media.”

Social media, according to her is, thus, only reflective of real life.

One of the initial tweets sent from the government’s FakeNewsBuster account said: “The objective of social media is information, education and knowledge sharing. It should be based on truth and should not spread #FakeNews and disinformation, to achieve ulterior motives.”

But what is fake news?

The term was initially meant to describe news that is not correct but has been politicised in recent times and is now being used as a synonym for partisan propaganda. “You repeat things and you repeat things and you say them [in] different ways and you say them over time and it eventually starts to sink in,” is how media columnist Margaret Sullivan explained it in a BBC interview. She was analysing how Donald Trump has made the term fake news a part of mainstream media conversation.

“Fake news is no longer just news that is not true. It has become a buzz word,” says journalist Umer Ali who is doing research on the subject as part of his studies in Europe. He finds it problematic that the government is getting to decide what fake news is. “Just consider what is happening in the United States where Trump labels as fake news anything that he does not like or is not in the favour of his government.”

Ali is worried that the government in Pakistan may also try to use this catchphrase to silence its critics. The authorities, he alleges, are already posting screenshots of social media posts by a select group of journalists on FakeNewsBuster account in order to undermine their credentials.

A few months before the account was set up, in June this year to be exact, ISPR’s head Major General Asif Ghafoor addressed a press conference in which he alleged, among other things, that social media was being used against the security of the state and its institutions. He pointed out how there was an increase in anti-Pakistan propaganda on social media, with many accounts promoting anti-army content by either distorting or manufacturing facts.

Ghafoor also showed a slide that explained how someone “tweets against the forces and the state” and then those tweets are retweeted. “But who is retweeting them?” he asked, signalling to several boxes in the slide which mentioned unnamed “political figures”. These political figures, he said, were using their own Twitter handles to retweet, praise and spread this “anti-state propaganda”.

Ghafoor then highlighted the need to regulate social media.

Two months later, information minister Chaudhry announced that the government was working on setting up a “unified” regulatory body for all types of media, including newspapers and magazines, television and websites, and also social media. In October, he briefed a standing committee of the Senate on the subject and said that, under the new regulatory regime, “no one will be able to defame anyone”.

Efforts to have social media accounts blocked and posts deleted are also well under way in Pakistan. And Twitter, it seems, is more willing to accept requests for the removal of contents and suspension/blocking of accounts than before. Between January 2012 and December 2017, it denied all the 156 requests by the Government of Pakistan to remove contents, according to its own global transparency report. In recent weeks, however, it has suspended or blocked many accounts including the one operated by Khadim Hussain Rizvi, a pro-blasphemy law rabble rouser now in protective custody of the state.

Two journalists, Taha Siddiqui and Gul Bukhari, also claim that Twitter has recently warned them against uploading “objectionable content” on their Twitter accounts. The two have a history of alleged runs-in with some powerful tormentors. Siddiqui ran away to France in January this year after accusing some unknown persons of trying to abduct him in Islamabad. Gul also disappeared briefly in Lahore in June this year.

Could there be a better way to deal with fake news and misinformation than launching a selective crackdown on social media or imposing a blanket censorship?

Some conceptual clarity may help.

Satire, parody, misleading content, imposter content, fabricated content and manipulated content all need to be seen separately from each other and dealt with accordingly. The Ethical Journalism Network, a global conglomerate of journalists and media organisations, also highlights the need to clear the confusion about what constitutes fake news and what does not. In order to do so, the network has released its own definition of fake news. “Information deliberately fabricated and published with the intention to deceive and mislead others into believing falsehoods or doubting verifiable facts,” is how it defines fake news.

If nothing else, this definition sets apart propaganda, “alternative” facts, and malicious lies from journalism.

Apart from definitional ambiguities, there is also a lot of legal confusion around fake news.

Consider this tweet by the government’s FakeNewsBuster account: “It is the prime responsibility of all social media users to share information/posts that are factually correct. Reporting fake and baseless news on sensitive issues may lead to unrest among public and is a punishable crime under the Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act 2016.”

This message lays down the problem of dealing with fake news and partisan propaganda masquerading as journalism under the current laws: Unless you connect the fake and propagandist social media contents to “sensitive issues” and “unrest among public”, the generators and disseminators of such contents cannot be prosecuted and punished. “Fake news in isolation is not punishable. It all comes down to the consequences it can lead to,” says a lawyer who has contributed to the drafting of the Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act 2016.

This is also obvious from the law itself. “Whoever prepares or disseminates information, through any information system or device that advances or is likely to advance interfaith, sectarian or racial hatred shall be punished with imprisonment for a term which may extend to seven years or with fine or with both,” reads its Section 11.

The only other legal provision available to try someone for producing and propagating fake news, according to the lawyer, is the defamation law. If fake news or propaganda harms someone’s reputation, they can always move the courts of law to seek damages for that, he says.

In short, no legal and judicial tool directly deals with fake news and propaganda. This makes it difficult for the authorities to come up with a clear procedure to take action against those involved in producing and promoting it. “Our job is to only monitor social media’s content and make the public aware,” says Mian Jahangir, who handles the FakeNewsBuster account and is director-general of the federal information ministry’s cyber wing. “We encourage people, especially journalists, to [publicly] rectify false news if they see/report it,” he says. Action is taken only by the FIA and the PTA, he says.

This three-way division of roles and responsibilities in dealing with the menace of fake news and propaganda has put journalists under triple pressure to watch their step constantly. They will be in trouble if their reports or analyses fall on the wrong side of any of the three departments.

To add to their woes, social media is abuzz with posts that target them.

Between October 20 and November 16 this year, at least six hashtags trended on Twitter which directly targeted journalists and journalism in Pakistan. Those partaking in these hashtags have portrayed journalists as “biased” and “propagandists”.

One of them, #BikaoMedia, accused journalists of spreading disinformation and urged the government to take “strict action” against them. “Everyone knows that Media is the main tool of enemies in 5th Generation Hybrid war — the main tool with [which] they will make up your mind … will make you watch what they want … don’t be at this destructive route #BikaoMedia,” read a tweet posted under the hashtag.

Another hashtag, #SayNoToFakeJournalism, generated almost 14,000 tweets (of which about 200 were identified as spam/bots). It went to the extent of reporting unverified news involving the Chief Justice of Pakistan Mian Saqib Nisar. “Pakistan Electronic Media Regulatory Authority (PEMRA) has been asked to take urgent action against fake web channels and the impersonators who were plundering the people through these web channels,” a message under the hashtag read. “According to details, an owner of a TV channel has appealed to [the chief justice] to take action against fake web channels and especially against fake journalists and impersonators who were looting the people through social media,” read another message under the same hashtag.

“This intersection of troll armies with journalists is not healthy for democratic discourse,” says journalist Amber Rahim Shamsi who hosts a television talk show. “When the gatekeepers of information are being compromised, people will rely on word of mouth and that is how fake news spreads,” she explains.

Dawar Butt, who operates a fact-checking social media service ‘Surkhi’ from Lahore, also argues that “believability is no longer” a function of truthfulness. It now depends on the perceived credibility of the source of the news, he says.

The remedy, according to him, lies in fact-checking. “It is no longer an option that you can ignore. It is a necessity,” Butt says. “Citizens have to get above their partisanship and make it a habit to do background checks, not falling victim to confirmation bias in false news items.”

Confirmation bias can, indeed, distort fact-checking as well, making it partial and partisan. The government’s FakeNewsBuster account, for instance, continued to give the federal science and technology minister Azam Swati a clean chit even when evidence was mounting against him that he misused his authority to have the Islamabad police chief transferred in October this year.

Some seemingly non-government initiatives, such as @PakFactCheck, are also emerging in order to use fact-checking as a tool to support partisan narratives.

“Learn what’s true and what’s false | Harvesting Deep Web & OSINT| Non-Partisan | Verification of the Factual Accuracy of News & Analysis | Pvt Think Tank |,” reads the bio of @PakFactCheck on Twitter. The account talks about “anti-state activists”, “fascist” journalists and “subversive news organisations” and is followed by over 11,000 users.

[N[ate Hendrick’s social media bio listed him as a “traveller by profession, journalist by passion”, working as the Rossiyskaya Gazeta’s foreign correspondent in South Asia. He had nearly 10,000 followers and earned quote tweets/comments from prominent Twitter users, including musician Salman Ahmad. His account was also ‘verified’ as genuine by Twitter with a blue check mark.

One Twitter poll posted by Hendrick asked Pakistanis whether they preferred Vladimir Putin or Donald Trump — 91 per cent of the respondents sided with Putin. “Amazed at the way Pakistani leaders think going to answer questions regarding corruption is an achievement. Here in the West, leaders usually resign before commissions, but in Pakistan it’s totally the opposite,” he once tweeted, garnering over 1,700 retweets.

From July 2, 2017, to July 10, 2017, Hendrick tweeted more than 50 times on issues ranging from Iran’s Kashmir policy to CNN, adopting the tone of a bemused but naive observer with ties to Russia. “He would comment on Pakistani landscapes and food, interspersed with criticism of Sharif’s role in the unfolding Panama Papers inquiry,” wrote Russell Brandom, a policy editor at Report — The Verge, an online American publication focused on technology.

There was only one thing odd about the account: its handle, @NateBussey59, did not match its screen name, Nate Hendrick. Further investigations by Brandom revealed that the account was fake. Hendrick never existed.

His account’s social media popularity points to another dimension of digital politics — the influence of a foreign perspective on nationalism. Richard Harris is another such influencer as far as Pakistan is concerned.

“Business owner | Lahore | Brussels |South Asian History | Pakistan | Urdu | Qeema Naan and a jug of lassi,” reads his bio on his Twitter profile created in January 2017.

His Twitter presence remains rather unremarkable in terms of numbers – he has only 2,200 followers – but curiously inconsistent in terms of activity. There are days when he tweets more than 50 times a day. On other occasions, his account remains dormant for days. What is even more intriguing is that Richard rarely tweets original content. A vast majority of his 15,000 plus tweets – all focused on Pakistan – are either responses to other users or quote tweets (that is, retweets with comments). He actively responds to those Twitter users who comment about Pakistan in a critical manner and challenge the official narrative. He often engages in Twitter arguments with journalists or those who he labels as “liberals” or “pseudo-liberals”.

Richard’s profile offers little personal or professional information. He has claimed in some tweets that he visits Pakistan to meet his wife and children but his tweets display an in-depth knowledge of Pakistan which is unusual for an occasional visitor. He also seems to be extremely familiar with civic and political problems in places such as Karachi and Lahore. He once tweeted about purchasing an uninterrupted power supply (UPS) system to counter load-shedding. At another moment, he wrote about Karachi’s electoral politics, citing local references.

Cynthia D Ritchie is a similar influencer though with a much larger outreach — and a highly public persona that helps her attract attention and earn credibility.

A self-described traveller and blogger, Cynthia is an American who has a Twitter account operational since January 2009. With only 7,500 tweets in almost a decade, her account has an unusually high number of followers — over 46,000. A vast majority of her tweets are also about Pakistan.

There has been a visible surge in her Twitter activity since 2013. Since October this year, she has also started writing opinion pieces in a Karachi-based English daily The Express Tribune. Her pieces focus on the need to see “Pakistan through a different lens” and also question American policies towards Pakistan.

Cynthia frequently uses Urdu phrases and words in her tweets and has also visited many places which remain inaccessible to many Pakistanis. In October this year, she visited North Waziristan, a major hub of religious terrorism where the Pakistan Army is still fighting against the remnants of the banned Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan terrorist outfit.

“The North Waziristan you don’t hear about in mainstream media. For Pakistan watchers, I don’t have to remind you with devastating ‘before’ images. Instead, I will show you the results, thus far, of the ‘clear, hold, build, transfer’ efforts of Pakistan’s armed services,” she wrote, sharing pictures of her visit on Twitter. This message generated 640 retweets and 18,000 likes.

When a digital magazine, Global Village Space, asked her about the reason behind her interest in Pakistan, she replied: “Look, Pakistan has its challenges, so you will be frustrated, you might even be frightened, but you will always be fascinated.” Her signature hashtags include #PositivePakistan, #EmergingPakistan, #ADifferentLens and #NarrativeEconomics.

Her pro-Pakistan tweets would perhaps be less believable if these were not coming from a white, American woman who now calls Pakistan her home.

She tweeted on August 19: “Happy to share I am registering my company #ADifferentLens media productions and strategic PR in #Pakistan. Pakistan is my home and I’m proud to invest in this country! Request duas for our success in helping the People of Pakistan and globally. #NewLogo US<3Pak.”

Hashtags for this story were analysed using Project Shikari. Bot/spam tweets were identified through machine learning and artificial intelligence algorithms with an accuracy rate of 66 per cent.

The writer is a social scientist by qualification and a staffer at Daily Dawn.

This article was published in the Herald's December 2018 issue. To read more subscribe to the Herald in print.