After the December 2014 Army Public School (APS) massacre in Peshawar, Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif promised there would be “no differentiation between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ Taliban”. In February 2015, Chief of Army Staff General Raheel Sharif announced in Kabul that “the enemies of Afghanistan are the enemies of Pakistan”. Sartaj Aziz, advisor to the prime minister on national security, repeated the same sentiment in May that year. He was trying to overcome the damage he had done in November 2014, when he told BBC Urdu that the enemies of Afghanistan and the United States were not necessarily threats to Pakistan. But it looks like the Sartaj Aziz-Big Bill Broonzy counterterrorism policy is still in effect.

Born in Arkansas, grown to fame in Chicago, bluesman Broonzy summarised the American racial order of the time in a song:

They says if you was white, should be all right

If you was brown, stick around

But as you’s black, m-mm brother, git back git back git back

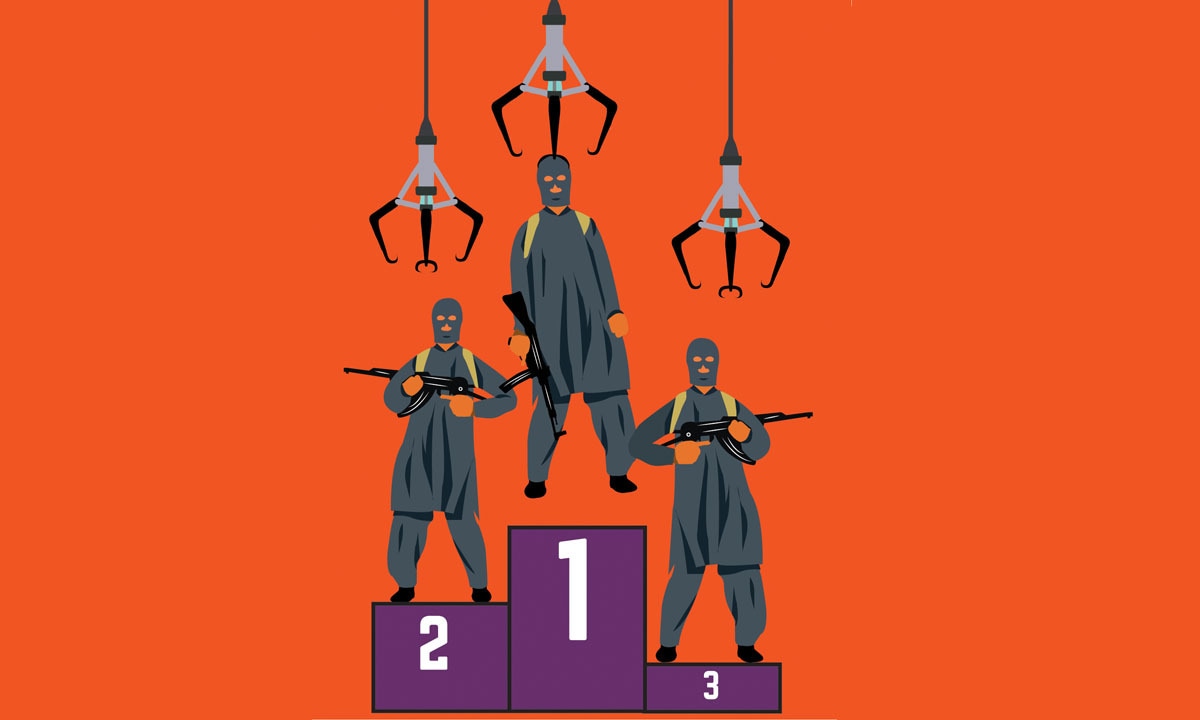

The Pakistani terrorist groups that target India are all right. The supposedly banned Jaish-e-Muhammad (JeM) is alleged to have attacked the Indian airbase in Pathankot on January 2, 2016. Its leader, Masood Azhar, has been taken into “protective custody,” but the organisation’s headquarters in Bahawalpur functions as always. So does Laskhar-e-Taiba (LeT), under the name Jamaatud Dawa (JuD), and its leader – Hafiz Saeed – is treated as a respected leader in the media, even though the United Nations Security Council (including Pakistan’s all-weather friend, China) has designated him a terrorist.

Also read: The crackdown on Hizbut Tehrir intensifies

For now, at least, the Afghan Taliban can stick around. The official spokesman of the so-called Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan (IEA), whose Twitter account places him in “Sindh, Pakistan” (Karachi, presumably) proudly claimed responsibility for the murder of seven young journalists of Afghanistan’s Tolo TV in Kabul on January 21. By far the most important Taliban group, the IEA operates more or less openly out of Quetta and Karachi. Pakistan’s policy is to persuade it to join in on the talks with the Afghan government, but it refuses to enforce it’s own laws (to say nothing of the National Action Plan against terrorism) against the Afghan Taliban’s military and terrorist infrastructure on Pakistan’s territory. The United States bears responsibility for undermining former Afghan President Hamid Karzai’s early efforts to bring the Taliban out from the cold and hold negotiations with them, leaving them no choice but Guantanamo or hide in Pakistan. A political settlement might offer them a better choice, but only if Pakistan stops enabling their violence.

The army launched operation Zarb-e-Azb to force the various fragments of the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) to git back — and so they did; they have gone to parts of Afghanistan under the secure control of the Pakistan-based Afghan Taliban, whom Pakistan refuses to target. That is why the accusations from Pakistan’s General Headquarters that the commander of the attack on Bacha Khan University in Charsadda came from Afghanistan rings hollow. Efforts to stamp out the one group of terrorists that the Pakistan military really treats as enemies will leave Pakistan undefended, as long as the TTP can seek refuge with other terrorist groups that Pakistan still seeks to use for political ends.

All terrorism is abhorrent and illegal under international and Pakistani national law. It is inevitable that the Pakistani state will crumble when its own security forces refuse to enforce the law unless foreign governments meet Pakistan’s demands — a classic case of threatening to shoot oneself if demands are not met.

But not all groups that use terrorism for political ends are the same. The undifferentiated use of so-called “counterterrorism” tactics (military operations and drone strikes) against them has proved a failure. Countering terrorism requires a political strategy.

Indian airmen in Pathankot were collateral damage in an attack aimed ultimately at Nawaz Sharif and his efforts to lessen tensions with India. The government of Pakistan has to remove terrorism from the India-Pakistan relationship, and India’s restraint is helping it. But that restraint can continue only as long as Pakistan takes firm measures against those guilty of anti-Indian terrorism.

This originally appeared in the Herald's February 2016 issue. To read more, subscribe to the Herald in print.

This story has been co-published by The Wire, India.