"There is formidable industrial activity at present in progress, which is inevitably and constantly at the back of our minds; at every moment either directly or through the medium of newspapers and reviews, we are presented with objects of an arresting novelty whose why and whereof engrosses our minds, and fills us with delight or fear."

– Le Corbusier, Towards a New Architecture, 1923

In the age of the machine, any city is susceptible to something new or revolutionary. But a city like Karachi that is consistently being developed and broken becomes part of a vicious cycle of construction and destruction. On one hand, the urban sprawl continues to expand with new sites, architecture and infrastructure, while on the other, one also finds crumbling buildings and demolitions … ruins. The unknown runs through the veins of the city like a disease, which has given rise to a new idea of protection, self-sustenance and security.

Over a period of several years, the changing political landscape of the city has altered its physical landscape, but this change is hardly noticeable to uninterested passers-by since it has happened over such a long period of time. Barricades, check posts and entrenchments (usually made out of sand bags) that previously cordoned off only certain localities are now scattered about almost everywhere.

Seema Nusrat’s study of the city examines this very culture of security that has taken over the architecture of Karachi in a way that appears to be all too fashionable. Her exhibition at the Gandhara Art Space, from March 23 to April 23, 2017, is aptly entitled Proposals Towards a New Architecture.

In the recent past, the city of Karachi has been subject to various operations resulting in the creation of entrenchments and ranger check posts around all major arteries of the city. Isolated incidents of terror as well as incidents of violence and brutality are the prime reasons that justify these fortifications.

As fear and freedom intertwine, the idea of securing and sealing territory is pursued obsessively. However, it is not done in isolation. Instead, it is rendered and embedded within the architecture as a decoration that not only camouflages, but also beautifies the protected territory.

Nusrat’s works make a concerted effort at presenting this aspect of fortifications that has become a part of the new architecture. It is particularly well-represented in her work, Planter I & II, where the barbed barrier that is encased within a wire mesh also has a lush green turf.

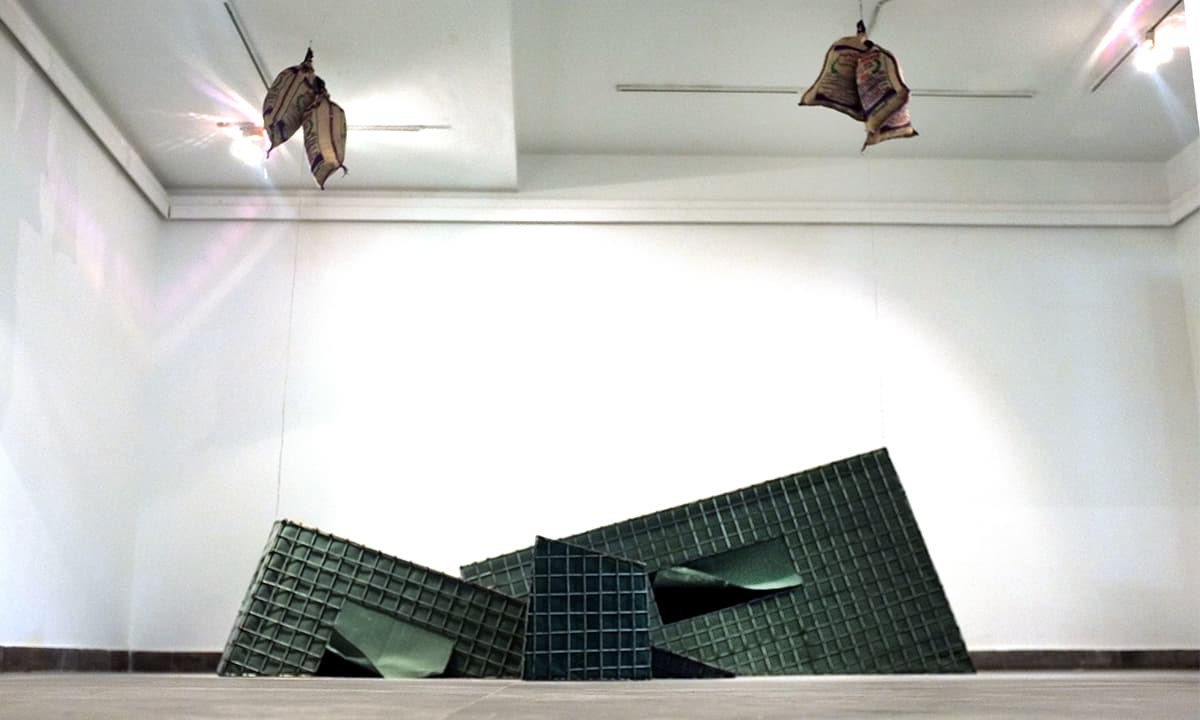

Similarly, the works, Domestic Elevations I, II, III & V, also indicate the façade as a ‘gilded cage’ that is thoroughly protected from the outside. These facades seem to be impervious to the violence outside. The shape of these elevations is particularly interesting, as the segmented blocks closely resemble the squared and rectangular windows found in the generic architecture of Karachi, as well is in paramilitary booths or posts.

In the photographic works, the artist forms collages of architectural components that are, yet again, made out of barricades. As the barricades themselves become the masonry, the result is quite eerily that of a fortified dollhouse.

Another example of this kind of construction is the green-tented, wire-encased structure that lay ominously on the floor of the gallery space. Its sheer scale and placement, made to resemble a collapsed camp, both intimidating and frightful.

In another work, Containing the City, the grey skyline is yet again encased and protected within the wire-mesh as if to indicate that the entire city has been militarised. From a single, fortified building to dozens, the city is becoming more and more grey as well as barbed, and it may not be naïve to believe that it is slowly becoming a barracked battlefield.

Nusrat’s work is highly political and is represented as such by the curator, Zarmeene Shah, to the best of that effect.

The question, however, remains: whether this increasingly visible new architecture will be secure enough. It has most certainly become noticeable. And that idea itself leads us to a fearsome possibility towards a likely reality.

The writer is a lecturer and scholar